Abstract

There are numerous reports of spiders that have become established outside of their native ranges, but few studies examine their impact on native spiders. We examined the effect of the European hammock spider Linyphia triangularis (Araneae, Linyphiidae) on the native bowl-and-doily spider Frontinella communis (Araneae, Linyphiidae) in Acadia National Park, Maine, USA. First, we added L. triangularis to established plots of F. communis. Significantly more F. communis abandoned their webs when L. triangularis were added compared to control plots. Second, we tested whether F. communis were deterred from building webs in areas where L. triangularis was established. Significantly fewer F. communis built webs on plots with L. triangularis than on control plots. In both experiments, L. triangularis sometimes took over webs of F. communis or incorporated F. communis webs into their own webs, but F. communis never took over or incorporated L. triangularis webs. Competition between L. triangularis and F. communis for both webs and web sites may contribute to the decline of F. communis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Invasive species may harm natives through competitive displacement, which occurs when a species is driven from its habitat and prevented from reestablishing by the indirect or direct effects of a superior competitor (Reitz and Trumble 2002). Invasive species may displace natives through indirect interactions by preempting access to a resource (e.g., Blakley and Dingle 1978), exploiting it more efficiently than do natives (e.g., Hill et al. 1993), or degrading it (e.g., Hougeneitzman and Karban 1995). Direct agonistic interactions between two species over a resource can also result in displacement (e.g., Amarasekare 2002). In some cases, one taxon may usurp a resource constructed by another, such as the takeover of European honeybee hives by Africanized swarms (Schneider et al. 2004).

Web-building spiders may potentially compete for several different resources, including web sites (Riechert 1979; Harwood and Obrycki 2005), prey (reviewed in Wise 1993) and sometimes webs themselves (Eichenberger et al. 2009; Hoffmaster 1986; Jakob 1991, 2004). Losing webs to competitors is likely to have fitness consequences, as webs are necessary for prey capture and are energetically costly to produce (e.g., Jakob 1991; Pasquet et al. 1999; Herberstein et al. 2000; Venner et al. 2003, 2006). In the most extreme instances, web takeovers also result in the usurper preying upon the host spider (Toft 1988; Perkins et al. 2007).

Reports of biological invasions of exotic spider species are accumulating rapidly. Invaders come from a range of families, including Agelenidae (Baird and Stolz 2002), Amaurobiidae (Vetter 1994), Araneidae (Martinez 1993), Gnaphosidae (Brescovit et al. 2008), Linyphiidae (Eichenberger et al. 2009; Jennings et al. 2002; Vink et al. 2004), Nephilidae (Kuntner 2005, 2006), Pholcidae (Gertsch and Peck 1992; Huber 2001), Prodidomidae (Almeida-Silva and Brescovit 2008), Salticidae (Hutchinson and Limoges 1998; Paquin and Dupérré 2003; Bradley et al. 2006), Theriididae (Gruner 2005; Nihei et al. 2004; Hann 1990; Nyffeler et al. 1986), and Zoropsidae (Griswold and Ubick 2001). In a wide variety of taxa, global travel spreads invasive species (e.g., Brawley et al. 2009; Tatem 2009), and evidence suggests that this is also true for spiders (Kobelt and Nentwig 2008). Like many other invasive species (reviewed in Holmes et al. 2009), invasive spiders generate economic costs for control, cleaning of buildings, and, for some species, treatment of bites (reviewed in Kobelt and Nentwig 2008). Spider invasions are likely to become increasingly common (Kobelt and Nentwig 2008). Invasive arthropod predators can have complex and unpredictable impacts on native communities (Snyder and Evans 2006), so an increased focus on the ecological effects of invasive spiders is warranted.

We studied the invasive sheet-web spider, Linyphia triangularis (Araneae: Linyphiidae), a native of Europe and Asia. The first record of this spider in the United States, to our knowledge, is from 1983, and it is now well established in Maine in the northeastern USA (Jennings et al. 2002). In its native range, L. triangularis frequently competes with its congener, L. tenuipalpis, for web sites (Toft 1987, 1990). Both species are aggressive and engage in heterospecific web invasion, which can result in web sharing, web takeover, or predation on the host spider (Toft 1988). Conflicts are most often won by the larger spider, typically L. triangularis (Toft 1990). The large size, competitive ability, and aggressive nature of L. triangularis may have contributed to its successful establishment in North America (Jennings et al. 2002; Houser 2007).

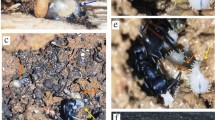

We expect that in North America, L. triangularis will have the greatest impact on species that are similar in size and habitat. Correlational evidence suggests that L. triangularis has a negative effect on natives. In Maine, transect sampling over 4 years (2003–2006) showed a decline in native linyphiids relative to L. triangularis in forest habitat (Jakob, in preparation). In coastal areas where L. triangularis density was high, native linyphiid spiders were virtually absent, but where L. triangularis density was low, native spiders were more common (Jakob, in preparation). Behavioral data suggest a possible mechanism: Houser (2007) staged interactions between L. triangularis and the native bowl-and-doily spider (Frontinella communis Hentz), and found that L. triangularis frequently took over webs. This observation was particularly interesting given that these species build distinctly different webs. The web of L. triangularis is flat, gently domed, or saddle-shaped, and the spider hangs beneath the web surface. That of F. communis, as its common name implies, consists of a flat “doily” under a densely-woven prey-capture “bowl,” under which the spider hangs. When in an F. communis web, L. triangularis also generally hangs beneath the bowl.

Here we use an addition/removal experiment to determine whether L. triangularis drives F. communis from established webs, as might happen when L. triangularis populations expand into a new region. We also test whether the presence of L. triangularis deters F. communis from settling in a site and building webs, which addresses whether the native spider is likely to be able to recolonize areas invaded by L. triangularis.

Materials and methods

Selection of target densities for our experiments

Both experiments were conducted in the second half of August 2006 at the Schoodic Point section of Acadia National Park (Hancock County, Maine). At Schoodic Point, L. triangularis density varies depending on microhabitat. Densities are highest in small spruce, crowberry, juniper, and other low vegetation, especially along coastal margins, roadsides, and power-line cuts. In these areas, spider webs can be packed so closely they are nearly touching. For our experiments, we selected 11 spiders per m2 as our target density for L. triangularis, a density commonly reached on small spruce trees (Picea rubens and P. glauca) similar to those used in our study (unpublished data). Thus, our experiments mimic the interaction between native spiders and a well-established population of L. triangularis, rather than the interaction between species at the beginning of the invasion when L. triangularis were few.

Although F. communis is found at Schoodic, its population density may have been reduced since the invasion of L. triangularis. To better estimate the pre-invasion density of F. communis, we surveyed spiders at Cobscook Bay State Park (Washington County, Maine). Cobscook Bay has habitat similar to Schoodic, primarily young spruce trees and forbs along coastal margin. However, L. triangularis is relatively uncommon, comprising only 10% of individuals of the four largest linyphiid species (L. triangularis, Pityohyphantes phrygianus, F. communis, and Neriene radiata), vs. more than 95% in similar habitat at Schoodic Point (Jakob, in preparation). We estimated density of F. communis in high-density areas of Cobscook Bay by selecting five small spruce trees (Picea rubens and P. glauca) similar in size and shape to our study trees at Schoodic Point (see below), measuring them, and counting the number of spiders. Density ranged from 5 to 8 per m2, so we selected seven F. communis per m2 as our target density.

Experiment 1: L. triangularis added to established plots of natives

The first experiment mimics the invasion of L. triangularis into established areas of F. communis. Following Houser (2007), we selected isolated trees as plots, which made it easier to manipulate and maintain spider densities. We chose tree species used by both species of spiders, including red spruce (Picea rubens), white spruce (P. glauca), balsam fir (Pinus balsamea) and jack pine (Pinus banksiana). Plots were paired by tree species, estimated tree volume, and similarity of surrounding habitat. We chose trees that were short enough so that we could inspect the entire tree (average height: 1.29 ± 0.04 m, diameter: 1.18 ± 0.24 m). A member of each pair was randomly assigned to either a control or L. triangularis-added (hereafter Lt+) treatment. At the start of the experiment, we cleared all spiders and unoccupied webs from the plots. Spiders found in the plots were orb weavers, tangle-web weavers, Pityohyphantes sp., F. communis, L. triangularis, and several unidentified species.

Based on the target density described above, we calculated the number of F. communis required for each plot. Because preliminary trials showed that not all translocated F. communis establish webs, we released 1.5 times this number. We collected F. communis from other areas in the Park and held them for no more than 48 h prior to release. Spiders were gently released onto separate branches of the trees, a minimum of approximately 50 cm apart in order to reduce the probability of interactions. We surveyed trees daily for the next 2 days and adjusted the numbers of spiders where necessary in order to reach the target density for F. communis. We also removed all spiders of other species from the plots. We labeled webs with unique ID numbers on tape folded over nearby branch tips.

By the third day, the plots were at or within one individual of their target densities of F. communis in completed webs (mean ± SE: 7.77 ± 0.49 spiders per plot, range 5–11), and we began the manipulation. We calculated the number of L. triangularis to be added to each Lt+ plot and released them in the same manner as we released native spiders (11.81 ± 1.20 spiders per Lt+ plot, range 6–18). On subsequent days, we surveyed the plots and counted the number of individuals of each species and the number of unoccupied webs. We removed several L. triangularis that colonized control plots. After 2 days, surveys were halted by wind and rain that destroyed webs.

We categorized interspecific web invasions as either web takeover (a heterospecific intruder was on the prey-capture sheet of the resident’s web, and the resident was gone), or a web incorporation (the intruder built its web using the supports or sheet of an inhabited heterospecific web).

We used pairwise nonparametric statistics to compare the percent of F. communis that remained on Lt+ plots to the percent remaining on the paired control plots (N = 11 pairs).

Experiment 2: Natives added to plots with and without L. triangularis

We used a subset of the plots pairs from Experiment 1 (N = 8 pairs of trees; average height: 1.29 ± 0.05 m, diameter: 1.17 ± 0.063 m). On one plot of each pair (the Lt+ plot), we released L. triangularis that had been captured elsewhere in the Park and held in vials for not longer than 48 h. Because preliminary observations suggested that L. triangularis is quite vagile, we released double the number required to reach our target density. During the establishment period, we adjusted the number of L. triangularis as necessary, and all plots were at or within one individual of their target densities after 3 days (mean ± SE: 5.25 ± 0.41 spiders per plot, range 4–7).

On the third day after beginning L. triangularis establishment, we added F. communis to each plot (mean ± SE: 12.65 ± 0.77 spiders per plot, range 8–17). We surveyed the plots for the next 3 days, removing several immigrant L. triangularis from the control plots and counting the number of individuals of both species on each plot. We also searched for unoccupied webs. We numbered each F. communis web as before. We categorized web invasions as in Experiment 1.

We used pairwise nonparametric statistics to compare the percent of F. communis building webs on Lt+ plots to the percent that did so on the paired control plots.

Results

Experiment 1: L. triangularis added to established plots of natives

Fewer F. communis remained in their webs when the invader was introduced to the plot compared with control plots. On the first day after the release of L. triangularis (Day 1), 99% of F. communis on control plots remained in their webs, compared to 59% on Lt+ plots (Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test, tied Z = −2.934, P = 0.003; Fig. 1). On Day 2 after the release, 97% of F. communis on control plots remained in their webs, compared to 45% on Lt+ plots (tied Z = −2.934, P = 0.003; Fig. 1).

The percent of F. communis remaining on control plots and plots to which L. triangularis were added. The center lines of the boxes represent medians, box boundaries are the 25th and 75th percentiles, horizontal lines are 10th and 90th percentiles, and circles represent data points that are either less than the first quartile or greater than the third quartile by more than 1.5 times the interquartile range

In Lt+ plots, we observed takeovers and incorporations of F. communis webs by L. triangularis. On Day 1, there were seven takeovers and 11 incorporations. On Day 2, there were three additional takeovers and four additional incorporations. We saw no takeovers or incorporations in control plots.

Experiment 2: Natives added to plots with and without L. triangularis

Fewer natives built webs on plots where L. triangularis was established compared with control plots (Day 1: Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test, tied Z = −2.521, P < 0.02; Day 2: tied Z = −2.521, P < 0.02; Day 3: tied Z = −2.521, P < 0.02; Fig. 2). On the first day after natives were released (Day 1), 72% of the F. communis released on control plots built webs, compared to only 36% of F. communis released on Lt+ plots. F. communis that settled on Lt+ plots did not take over L. triangularis webs, but built new webs. On the day after the release of F. communis onto Lt+ plots, three newly-built F. communis webs of characteristic bowl-and-doily shape had been taken over by L. triangularis. On the following day, we saw three additional takeovers and an incorporation. By Day 3, 79% of F. communis released onto control plots had built webs, whereas on Lt+ plots only 34% of released F. communis remained.

The percent of F. communis settling on control plots and plots on which L. triangularis were present. The center lines of the boxes represent medians, box boundaries are the 25th and 75th percentiles, horizontal lines are 10th and 90th percentiles, and circles represent data points that are either less than the first quartile or greater than the third quartile by more than 1.5 times the interquartile range

Discussion

Our experiments suggest that the invasive spider L. triangularis is competitively displacing the native spider F. communis in Maine. In Experiment 1, F. communis abandoned their webs when L. triangularis were added to plots. In Experiment 2, F. communis was less likely to establish webs on plots that contained L. triangularis.

Several behavioral mechanisms played a role in the interactions between these two species. In both experiments, L. triangularis took over the webs of F. communis, evicting (or possibly consuming) the occupants. Second, L. triangularis incorporated webs of F. communis into their own webs, thereby making use of energetically valuable silk.

We have not measured the fitness costs to F. communis of web loss nor the fitness benefit to L. triangularis of gaining webs. However, the costs of web loss have been well documented in other species (reviewed in Venner et al. 2003). Webs serve as an extension of the sensory world of the spider and are necessary for detecting and trapping prey. Foraging success is directly linked to measures of fitness, such as survival and number and size of eggs (e.g., Uetz 1992). A spider that loses its web faces two costs. First, there is a lost-opportunity cost as the spider spends time searching for sites and building a functional web rather than foraging (e.g., Jakob et al. 2001). It may be time-consuming for F. communis spiders to find appropriate sites that provide support for their three-dimensional webs. Second, investment into the web itself is costly, both in raw materials and the energy needed to construct it. The largest energetic expenditures for spiders are in the locomotor activity and energy output associated with web building (reviewed in Venner et al. 2003). These costs can be substantial: in the pholcid Holocnemus pluchei, the calories in a web represent 4 days of foraging (Jakob 1991). The dense weaving and complex structure of the webs of F. communis are likely to require at least as many calories to construct as do the more delicate and simple webs of H. pluchei. Thus, we expect that, for F. communis, being forced to find a new location and then construct a web has meaningful lost opportunity and energetic costs, especially if it happens repeatedly.

From L. triangularis’ perspective, the ability to take over webs of native spiders rather than investing in its own web may facilitate its spread across the landscape. As described by Houser (2007), L. triangularis sometimes reshapes F. communis webs into a more typical L. triangularis web shape over the course of several days, and uses the web for its own foraging. This behavior suggests that native webs are indeed valuable resources for L. triangularis.

The presence of L. triangularis deterred F. communis from building webs. We do not know whether F. communis was actively driven off plots by L. triangularis, or whether F. communis detected cues from L. triangularis, such as airborne kairomones or chemical or tactile cues in silk deposited on the branches. Both airborne and contact pheromones are common across spider species (reviewed in Gaskett 2007) and interactions between other spider species are mediated by chemical cues. For example, the wolf spider Pardosa milvina avoids chemical cues, both airborne and in silk and excreta, of its predator Hogna helluo (Persons et al. 2002; Schonewolf et al. 2006). In areas where L. triangularis is at low density, a native spider seeking a web site may benefit from an ability to detect and avoid interspecific chemical cues and settle instead in an area free from competitors. However, in areas of high L. triangularis density, native spiders may encounter so many cues that they delay settling on a site to no advantage. The role of chemical cues can be easily assessed in laboratory experiments.

Our experiment used high densities of L. triangularis that reflect those in the most favorable habitat along the coast and other forest-edge areas, and thus our experiment does not mimic the initial invasion of L. triangularis when its numbers were relatively low. However, our experiment should be a reasonable approximation of the spread of high-density populations up and down the coastline and into favorable edge habitats, such as power line cuts. Houser (unpublished data) found that L. triangularis adults and large juveniles move quickly into areas cleared of spiders. Thus, the rapid spread of dense populations into neighboring favorable habitat is not unlikely. Nonetheless, further experiments using lower densities of L. triangularis would be informative and would give more insight into the timeline of its original colonization and spread.

The success of L. triangularis in the interactions documented here may result, in part, from a size advantage. Size is an important determinant of contest outcome in many spider species (e.g., Harwood and Obrycki 2005). For example, in Europe, contests over webs between invasive and native linyphiid species are won by larger spiders, irrespective of species (Eichenberger et al. 2009). Adult L. triangularis are substantially larger than adult F. communis. Houser (2007) measured samples of both species from June to October 2005, and found a maximum body length of 4.8 mm in F. communis (tibia-patella length, 2.4 mm), in contrast with 7.5 mm in L. triangularis (tibia-patella length, 5.5 mm; J. Houser, personal communication). These species matured at different times. L. triangularis grew steadily throughout the season, and with mature spiders in the population from late July through October. In contrast, F. communis populations were less synchronous, with most individuals maturing in early July, but with adults persisting throughout August. In the second half of August, when these experiments were conducted, both species were variable in size, but L. triangularis were substantially larger (mean ± SE, body length (mm): L. triangularis, 5.54 ± 2.26, N = 22; F. communis, 2.4 ± 0.15, N = 18; tibia-patella length (mm): L. triangularis, 3.87 ± 0.18; F. communis, 1.19 ± 0.10). Throughout much of the season, L. triangularis has a substantial size advantage. Even when L. triangularis and F. communis are closer in size, as is the case in June, L. triangularis has a competitive advantage (Houser 2007).

Our study focused on interactions for webs and web sites, rather than competition over food. Spiders can reduce the density of insect populations (e.g., Wise 1993). The high density that L. triangularis populations reach in suitable habitat may mean that it reduces the amount of insect prey available for native spiders. However, using a sticky-trap census, Houser (2007) found no evidence that L. triangularis causes a local reduction in flying insects. Further work is needed to establish definitively whether competition for prey is important in this system.

We expect that L. triangularis will expand its range in all directions, particularly in coastal habitats and in coniferous forests. The current range of L. triangularis has not been thoroughly mapped. Jennings et al. (2002) documented its presence in every Maine county except Aroostook, the most northern. To our knowledge, no systematic search in Maine has been carried out since that of Jennings et al., nor has one been extended beyond Maine’s borders.

Many compelling research questions about the biology of spider invasions remain. For example, our research and that of Houser (2007) suggests that the web-invading capabilities of L. triangularis may mean that it is particularly harmful to natives. Another well-established invasive spider, Holocnemus pluchei (Family Pholcidae) invades both conspecific and heterospecific webs (Jakob 1991 and unpublished observations). However, Eichenberger et al. (2009) found that although the alien linyphiid Mermessus trilobatus readily invades webs, the outcome of the competition for webs depends on body size rather than species identity. More studies are needed to show whether the behavior of web invasion is associated with a greater impact on native species, and perhaps improves the chances that a non-native species can become established.

References

Almeida-Silva LM, Brescovit AD (2008) First record of Zimiris doriai (Araneae, Prodidomidae) in Brazil. J Arachnol 35:554–556

Amarasekare P (2002) Interference competition and species coexistence. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 269:2541–2550

Baird CR, Stolz RL (2002) Range expansion of the hobo spider, Tegenaria agrestis, in the northwestern United States (Araneae, Agelenidae). J Arachnol 30:201–204

Blakley NR, Dingle H (1978) Competition: butterflies eliminate milkweed bugs from a Caribbean island. Oecologia 37:133–136

Bradley RA, Cutler B, Hodge M (2006) The first records of Myrmarachne formicaria (Araneae, Salticidae) in the Americas. J Arachnol 34:483–484

Brawley SH, Cover JA, Blakeslee AMH, Hoarau G, Johnson LE, Byers JE, Stam WT, Olsen JL (2009) Historical invasions of the intertidal zone of Atlantic North America associated with distinctive patterns of trade and emigration. Proc Nat Acad Sci 106:8239–8244

Brescovit AD, Frietas GCC, Simão DV (2008) Spiders from the island of Fernando de Noronha, Brazil. Part III: Gnaphosidae (Araneae: Arachnida). Revista Brasileira de Zoologica 25:328–332

Eichenberger B, Siegenthaler E, Schmidt-Entling MH (2009) Body size determines the outcome of competition for webs among alien and native sheetweb spiders (Araneae: Linyphiidae). Ecol Entomol 34:363–368

Gaskett AC (2007) Spider sex pheromones: emission, reception, structures, and functions. Biol Rev 82:27–48

Gertsch WF, Peck SB (1992) The pholcid spiders of the Galapagos Islands, Ecuador (Araneae, Pholcidae). Can J Zool 6:1185–1199

Griswold CE, Ubick D (2001) Zoropsidae: a spider family newly introduced to the USA (Araneae, Entelegynae, Lycosidae). J Arachnol 29:111–113

Gruner DS (2005) Biotic resistance to an invasive spider conferred by generalist insectivorous birds on Hawai’i Island. Biol Invasions 7:541–546

Hann SW (1990) Evidence for the displacement of an endemic New Zealand spider, Latrodectus katipo Powell by the South African species Steatoda capensis Hann (Araneae: Theridiidae). N Z J Zool 17:295–307

Harwood JD, Obrycki JJ (2005) Web-construction behavior of linyphiid spiders (Araneae, Linyphiidae): competition and co-existence within a generalist predator guild. J Insect Behav 18:593–607

Herberstein ME, Craig CL, Elgar MA (2000) Foraging strategies and feeding regimes: web and decoration investment in Argiope keyserlingi Karsch (Araneae: Araneidae). Evol Ecol Res 2:69–80

Hill AM, Sinars DM, Lodge DM (1993) Invasion of an occupied niche by the crayfish Orconectes rusticus: potential importance of growth and mortality. Oecologia 94:303–306

Hoffmaster DK (1986) Aggression in tropical orb-weaving spiders a quest for food. Ethology 72:265–276

Holmes TP, Aukema JE, Von Holle B, Liebhold A, Sills E (2009) Economic impacts of invasive species in forests: past, present, and future. Ann NY Acad Sci 1162:18–38

Hougeneitzman D, Karban R (1995) Mechanisms of interspecific competition that result in successful control of Pacific mites following inoculations of Willamette mites on grapevines. Oecologia 103:157–161

Houser J (2007) The invasion of Linyphia triangularis (Araneae: Linyphiidae) in Maine: ecological and behavioral interactions with native species. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst

Huber BA (2001) The pholcids of Australia (Araneae; Pholcidae): taxonomy, biogeography, and relationships. Bull Amer Mus Nat Hist 260:3–144

Hutchinson R, Limoges RM (1998) Premiére mention de Synageles venator (Lucas) (Araneae: Salticidae) por l’Amériqie du Nord. Fabreries 23:10–16

Jakob EM (1991) Costs and benefits of group living for pholcid spiderlings: losing food, saving silk. Anim Behav 41:711–722

Jakob EM (2004) Individual decisions and group dynamics: why pholcid spiders join and leave groups. Anim Behav 68:9–20

Jakob EM, Porter AH, Uetz GW (2001) Site fidelity and the costs of movement among territories: an example from colonial web-building spiders. Can J Zool 79:2094–2100

Jennings DT, Catley KM, Graham F (2002) Linyphia triangularis, a Palearctic spider (Araneae, Linyphiidae) new to North America. J Arachnol 30:455–460

Kobelt M, Nentwig W (2008) Alien spider introductions to Europe supported by global trade. Diversity Distrib 14:273–280

Kuntner M (2005) A revision of Herennia (Araneae: Nephilidae: Nephilinae), the Australasian ‘coin spiders’. Invert Syst 5:391–436

Kuntner M (2006) A monograph of Nephilengys, the pantropical ‘hermit spiders’ (Araneae, Nephilidae, Nephilinae). Syst Ent 32:95–135

Martinez MJ (1993) Introduction of a new orb-weaving spider, Neoscona crucifera (Lucas) (Araneae, Araneidae), into California. Pan-Pac Entomol 69:274–275

Nihei N, Yoshida M, Kaneta H, Shimamura R, Kobayashi M (2004) Analysis on the dispersal pattern of newly introduced Latrodectus hasseltii (Araneae: Theridiidae) in Japan by spider diagram. J Med Entomol 41:269–276

Nyffeler M, Dondale CD, Redner JH (1986) Evidence for displacement of a North American spider, Steatoda borealis (Hentz), by the European species S. bipunctata (Linnaeus) (Araneae: Theridiidae). Can J Zool 64:867–874

Paquin P, Dupérré N (2003) Guide d’identification des Araignées (Araneae) du Québec. Fabreries Supplément 11, p 251

Pasquet A, Leborgne R, Lubin Y (1999) Previous foraging success influences web building in the spider Stegodyphus lineatus (Eresidae). Behav Ecol 10:115–121

Perkins TA, Riechert SE, Jones TC (2007) Interactions between the social spider Anelosimus studiosus (Araneae, Theridiidae) and foreign spiders that frequent its nests. J Arachnol 35:143–152

Persons MH, Walker SE, Rypstra AL (2002) Fitness costs and benefits of antipredator behavior mediated by chemotactile cues in the wolf spider Pardosa milvina (Araneae: Lycosidae). Behav Ecol 13:386–392

Reitz SR, Trumble JT (2002) Competitive displacement among insects and arachnids. Annu Rev Entomol 47:435–465

Riechert SE (1979) Games spiders play. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 6:121–128

Schneider SS, Deeby T, Gilley DC, DeGrandi-Hoffman G (2004) Seasonal nest usurpation of European colonies by African swarms in Arizona, USA. Insectes Soc 51:359–364

Schonewolf KW, Bell R, Rypstra AL, Persons MH (2006) Field evidence of an airborne enemy-avoidance kairomone in wolf spiders. J Chem Ecol 32:1565–1576

Snyder WE, Evans EW (2006) Ecological effects of invasive arthropod generalist predators. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 37:95–122

Tatem AJ (2009) The worldwide airline network and the dispersal of exotic species: 2007–2010. Ecography 32:94–102

Toft S (1987) Microhabitat identity of two species of sheet-web spiders: field experimental demonstration. Oecologia 72:216–220

Toft S (1988) Interference by web take-over in sheet-web spiders. XI European Arachnological Colloquium. Technical University, Berlin

Toft S (1990) Interactions among two coexisting Linyphia spiders. Acta Zool Fenn 190:367–372

Uetz GW (1992) Foraging strategies of spiders. Trends Ecol Evol 7:155–158

Venner S, Bel-Venner MC, Pasquet A, Leborgne R (2003) Body-mass-dependent cost of web-building behavior in an orb weaving spider, Zygiella x-notata. Naturwissenschaften 90:269–272

Venner S, Chades I, Bel-Venner MC, Pasquet A, Charpillet F, Leborgne R (2006) Dynamic optimization over infinite-time horizon: web-building strategy in an orb-weaving spider as a case study. J Theor Biol 241:725–733

Vetter R (1994) A nonnative spider, Metaltella simoni, found in California (Araneae, Amaurobiidae). J Arachnol 22:256

Vink CJ, Teulon DAJ, McLachlan ARG, Stufkens MAW (2004) Spiders (Araneae) and harvestmen (Opiliones) in arable crops and grasses in Canterbury, New Zealand. N Z J Zool 31:149–159

Wise DH (1993) Spiders in ecological webs. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Acknowledgments

Adam Porter, Ethan Clotfelter, Jeremy Houser, Skye Long, Sarah Partan, Ted Stankowich, Mary Ratnaswamy and two anonymous reviewers provided helpful comments on the manuscript. We are deeply grateful to Daniel Jennings for his assistance with this project. We thank the Acadia National Park rangers, especially David Manski, Bruce Connery, Ed Pontbriand, and Bill Widener for assistance throughout this project and for permission to work at the Park. Michelle Bierman, Jim McKenna, and staff of the Schoodic Education and Research Center provided crucial logistical support. This research was made possible by a grant from the National Park Service and US Geological Survey awarded to E. M. Jakob, J. Houser and D. Jennings.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bednarski, J., Ginsberg, H. & Jakob, E.M. Competitive interactions between a native spider (Frontinella communis, Araneae: Linyphiidae) and an invasive spider (Linyphia triangularis, Araneae: Linyphiidae). Biol Invasions 12, 905–912 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-009-9511-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-009-9511-7