Abstract

Predators face the challenge of accessing prey that live in sheltered habitats. The coconut mite Aceria guerreronis Keifer (Acari: Eriophyidae) lives hidden beneath the perianth, which is appressed to the coconut fruit surface, where they feed on the meristematic tissue. Its natural enemy, the predatory mite Neoseiulus paspalivorus De Leon (Acari: Phytoseiidae), is larger than this pest and is believed to gain access to the refuge only after its opening has increased with coconut fruit age. In the field, experimentally enlarging the perianth-rim-fruit distance beyond the size of the predators resulted in earlier predator occurrence beneath the perianth and lower numbers of coconut mites. On non-manipulated coconut fruits, the predators gained access to the prey weeks later than on manipulated ones, resulting in higher pest densities of coconut mites. Successful biological control thus critically hinges on the size of the predator relative to the opening of the prey refuge.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Herbivores are selected to minimize the risk of being killed by predators and evolve traits necessary to colonize their host plants. In turn, plants defend themselves against herbivores by recruiting natural enemies as bodyguards (Price et al. 1980; Dicke and Sabelis 1988; Sabelis et al. 1999, 2008), for example by providing plant structures as shelter for predators (Janzen 1966; Beattie 1985; O’Dowd and Willson 1989; O’Dowd 1994; Risch and Rickson 1981; Sabelis et al. 1999; Wäckers et al. 2005). However, some herbivores can also benefit from plant structures to hide from predators (Magalhães et al. 2007). For example, herbivores are known to live in between the scales of flower bulbs (Lesna et al. 2004, 2014), inside dense forests of leaf trichomes (van Houten et al. 2013; Glas et al. 2012, 2014), and in shafts of grasses (Oldfield 1996; Lindquist and Oldfield 1996; Sabelis and Bruin 1996), which reduces the risk of predation.

Larger colonies of the coconut mite Aceria guerreronis Keifer (Acari: Eriophyidae) have been found almost exclusively on the surface of coconut fruits beneath the inner layer of the perianth (Howard and Abreu-Rodriguez 1991; Moore and Howard 1996; Navia and Flechtmann 2002; Navia et al. 2005; Lawson-Balagbo et al. 2008a; Negloh et al. 2011). In young coconut fruits (up to one month), the perianth is so tightly appressed that coconut mites have no access to the meristematic zone (Howard and Abreu-Rodriguez 1991). In the course of fruit development, the distance between the perianth rim and the fruit surface increases to the point where coconut mites can access the space beneath the perianth (Howard and Abreu-Rodriguez 1991; Aratchige et al. 2007; Negloh et al. 2010; Lima et al. 2012). This secluded microhabitat provides good conditions for development and reproduction of the mites, which feed on the meristematic tissue of the fruit. Furthermore, coconut mites are protected from adverse abiotic factors (i.e. rain, wind, sun radiation, temperature and humidity variation), and, as long as the perianth is tightly appressed to the fruit surface, they are also protected from their predators (Howard and Abreu-Rodriguez 1991; Sabelis and Bruin 1996; Ambily and Mathew 2003; Fernando et al. 2003; Siriwardena et al. 2005; Aratchige et al. 2007; Lawson-Balagbo et al. 2007b).

Predatory mites of the family Phytoseiidae are among the most important natural enemies of eriophyid mites (Lindquist et al. 1996; McMurtry and Croft 1997), but they are much larger than this prey and therefore have less opportunity to access the area under the perianth. Thus, coconut mites are protected from predation as long as predatory mites cannot enter. However, as the distance between the perianth rim and the fruit increases in the course of fruit development and in response to feeding by the coconut mite (Howard and Abreu-Rodriguez 1991; Aratchige et al. 2007; Lawson-Balagbo et al. 2007b), the predatory mites will eventually have access to the prey colony under the perianth.

Here, we tested the hypothesis that the distance between the perianth rim and the fruit (referred to as the refuge entrance below) is critical to biological control of coconut mites by predatory mites (Aratchige et al. 2007; Lawson-Balagbo et al. 2007b) in a small-scale field experiment. As candidate biological control agent, we selected the phytoseiid mite Neoseiulus paspalivorus De Leon, because it was the smallest, dominant predator on coconut fruits in the geographic area where the experiments were carried out (Falcon State, Venezuela) (F. da Silva, pers. obs.). We experimentally manipulated the opening of the refuge entrance and assessed the consequences of this manipulation for the population dynamics of coconut mites and predators. For further insight into the consequences of our experimental manipulations in the field, we carried out laboratory measurements of the size of living female predators at different phases of their reproductive cycle, comparing them with the refuge entrances after manipulation.

Materials and methods

Manipulation of the refuge entrance

The experiments were carried out from September 2010 to March 2011 on coconut palms of the ‘Criollo Malayo’ variety in a plantation at Urquia Farm, Municipality of Monseñor Iturriza, Falcón State, Venezuela. Coconut palms of 2–2.5 m height were selected, each receiving a single treatment that was applied to 12 one-month-old uninfested coconut fruits (2–3 cm of vertical calyx growth). Coconut mites usually do not infest the meristematic zone of unfertilized coconut flowers (Mariau and Julia 1970; Moore and Alexander 1987) and young fruits of up to one month old, because the perianth layers of the fruits are so tightly appressed to one another and to the fruit surface that the coconut mite has difficulties to enter (Howard and Abreu-Rodriguez 1991; F. da Silva pers. obs.). Prior to the experiment, extensive sampling of young coconuts was carried out in the field to verify the occurrence of mites. No mites were found on fruits of up to one month old. Furthermore, all fruits used in the study were previously inspected with the help of a pocket magnifier to verify that they were not infested. In case there were fewer than 12 uninfested fruits, an adjacent palm tree was used to complement the number of fruits. One fruit of each treatment was collected every other week to assess the number of coconut mites and predatory mites under the perianth. Thus, the experiment lasted for 24 weeks, but some treatments were terminated earlier because of premature fruit drop. All five treatments were replicated four times, so there were at least four trees per treatment.

The treatments involved manipulation of the refuge entrance through insertion of small rectangular (3 × 1 cm) PVC blades in between the inner perianth and the fruit surface, where coconut mite densities are highest (Lawson-Balagbo et al. 2007b; F. da Silva, pers. obs.). The PVC blades used were 40, 60, 80 or 120 μm thick. In the control, the refuge opening was not manipulated. In total 240 fruits were used in the experiment. The trees used in this experiment already harboured coconut mites and predators. We therefore used these naturally occurring populations. For practical reasons, it was unfeasible to carry out an extra treatment, excluding predators from coconut trees.

Each sampled fruit was stored in a paper bag and transported to the laboratory in coolers (at about 15 °C) to prevent mite dispersal. Fruits were inspected under a stereomicroscope after sequentially removing the perianth layers. The mites were first separated into phytophagous and predatory mites and then transferred to separate 2 ml Eppendorf tubes filled with 70 % ethanol. Other mites (i.e. astigmatids) were collected separately, but excluded from further analysis. To estimate the number of phytophagous mites, the content of each Eppendorf tube was poured into a Petri dish (5 cm diameter), and juveniles and adults were counted as groups of ten mites (hence overall numbers were multiples of ten). A sample of 100 phytophagous mites was taken from each Petri dish for mounting in Hoyer’s medium for later identification to species level. All juvenile and adult predatory mites were counted, because they were always found in much lower numbers than phytophagous mites. Eggs of phytophagous and predatory mites were not counted. Mites were all mounted in Hoyer’s medium, and identified to species level.

We compared the overall proportion of coconut fruits with prey and predators among treatments with a generalized linear model (GLM) with a binomial error distribution and a logit link function. The time series of the numbers of coconut mites and predatory mites per coconut fruit were analysed with a linear mixed effects model (LME from the nlme package of R; Pinheiro et al. 2014) with treatment (different refuge entrances), time and their interaction as fixed factors and replicate as random factor. We removed non-significant interactions and factors from the full models using the anova function of R. Factor levels were compared through a post-hoc analysis by grouping factor levels (Crawley 2007). All analyses were performed using R software (R Development Core Team 2013) and residuals were analysed to check for the suitability of the models and distributions used (Crawley 2007). Because the refuge entrance naturally increases with fruit age, we analysed the time to first occurrence of predators under the perianth with a time-to-event analysis using a Cox proportional hazards model (package survival of R; Therneau 2014). Treatments were compared with a general linear hypotheses test (glht function of the package multcomp of R; Hothorn et al. 2008).

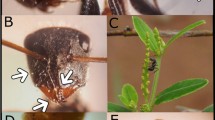

Assessment of predatory mite size

To compare the size of the entrance of the refuge to the size of mites, we measured the maximum height of the idiosoma of female predators. This was done by taking lateral pictures of mites walking on a tiny piece of PVC plate (1 mm wide, 5 mm long and 0.5 mm thick) floating on the water surface in a small groove of a plastic stick (Fig. 1). Before releasing the mites on the PVC plate, they were kept at 10 °C for approximately one hour to reduce their activity to facilitate photographing them. We used a Nikon D7000 digital camera mounted on a tilted Zeiss Universal microscope equipped with a Luminar attachment (comparable to a rigid bellows) and a Zeiss Luminar 40 mm f 4.5 at maximum extension for reproducibility. To calibrate measurements, pictures were first taken of a micrometer calibration slide with a scale (M) of 0.1 mm and this picture was then used as an overlay for the lateral view pictures of the mites. Subsequently, the image of the mite plus calibration overlay was loaded into MATLAB version 7.10.0 (MATLAB and Statistics Toolbox Release 2010a) for measurement of the grid size (n 1 pixels) and the distance between the dorsal and ventral extremes of the mite soma (n 2 pixels). The soma height (T) was calculated by multiplying the actual grid size in µm by the ratio of n 2 to n 1 (T = M n 2/n 1). This procedure was carried out four times, each with 20 virgin (and thus non-reproducing) females and 20 reproducing females. The virgin females included ten that had just undergone the last moult and ten females starved for two days after their last moult. The reproducing females included ten that had constant access to food and ten that were starved for two days since the onset of oviposition. Hence, a total of 40 female predators of each physiological condition was measured. We limited the measurements to adult females because this is the main dispersing stage of many predatory mite species (Johnson and Croft 1976; Charles and White 1988; Sabelis and Afman 1994).

Experimental design used to take photographs of mites. It consists of a tiny piece of PVC plate, floating in water contained in a groove of a plastic stick. The stick was attached to the edge of a mounting slide. The water level was maintained at the rim of the stick by regularly providing water from a syringe. This device allows photographing the mites placed on the floating PVC plate from a lateral viewpoint. A high resolution digital camera was used, mounted on a tilted Zeiss Universal microscope equipped with a Luminar attachment (comparable to a rigid bellows) and a Zeiss Luminar 40 mm f 4.5 at maximum extension for reproducibility

Data on the soma height were analysed with a GLM with reproductive and feeding status as factors with a gamma error distribution and a reciprocal link function. Contrasts among reproductive and feeding statuses were assessed with the glht function of the multcomp package (Hothorn et al. 2008).

Results

The coconut mite was found under the perianth of fruits in all treatments and was overall present on 123 fruits (62.4 % of the total). The proportions of infested fruits ranged from ca. 0.7 in the control to ca. 0.5 for fruits of which the refuge entrance was increased to 120 µm, but this difference was not significant (Fig. 2, GLM: \(\chi^{2}\) = 5.84, d.f. = 4, p = 0.21), showing that the experimental manipulation of the refuge entrance did not result in differences in occurrence of the pest on the coconut fruits. Across the treatments, the average number of coconut mites found under the perianth of a single fruit was 1438.8 (SE 158.6).

Overall proportions of coconut fruits (mean + SE) colonized by coconut mites (A. guerreronis; black bars) or predatory mites (N. paspalivorus; grey bars) as a function of refuge entrance (i.e. the distance between the rim of the perianth and the fruit surface: control, 40, 60, 80 and 120 µm). Shown are averages of 12 coconuts per replicate, four replicates per treatment. For coconut mites and predatory mites, proportions did not differ among refuge entrance sizes (GLM with binomial error distribution and logit link)

The numbers of coconut mites were significantly affected by the interaction of treatment with time (Fig. 3, LME: \(\chi^{2}\) = 13.4, d.f. = 4, p = 0.009). This was due to numbers of coconut mites in the treatment with the refuge entrance of 40 µm remaining high during the last eight weeks of the experiment, whereas the numbers of mites in the other treatments decreased during this period (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the average numbers of coconut mites through time were significantly lower in the two treatments with the largest refuge entrance (Fig. 3, inset: LME: \(\chi^{2}\) = 5.77, d.f. = 1, p = 0.016).

Average numbers of coconut mites (A. guerreronis) per coconut fruit with different manipulated refuge entrances (control, 40, 60 80, and 120 µm) at different times from 2 to 24 weeks. The inset shows overall average numbers of coconut mites through time per treatment; error bars represent SE. Different letters in the bars of the inset indicate significant differences (post-hoc comparisons through combining treatment levels after LME, p < 0.05)

The proportions of fruits with predators under the perianth differed among treatments, but this was only marginally significant (Fig. 2, GLM: \(\chi^{2}\) = 8.27, d.f. = 4, p = 0.082). The number of predators under the perianths ranged from zero to four. The effect of manipulating the refuge entrance on the number of predators was significant (Fig. 4, LME: \(\chi^{2}\) = 12.9, d.f. = 4, p = 0.012), and the effect of time was highly significant (LME: \(\chi^{2}\) = 21.5, d.f. = 1, p < 0.0001). Predators were found earlier under the perianth when the refuge entrance was larger (Fig. 4). To further test this, we performed a time-to-event analysis, which showed that this trend was significant (Fig. 5, Cox proportional hazards model: \(\chi^{2}\) = 20.03, d.f. = 4, p < 0.0005). Predators were found significantly earlier under the perianth of coconut fruits with the two largest refuge entrances. The treatment involving an intermediate size of the refuge entrance (60 µm) showed relatively more variation over time than the other treatments.

Average numbers of predatory mites (N. paspalivorus) per coconut fruit with different manipulated refuge entrances (control, 40, 60 80, and 120 µm) at different times from 2 to 24 weeks. Different letters in the legend indicate significant differences among time series (contrasts through combining treatment levels after LME, p < 0.05)

Effect of manipulation of the refuge entrances (control, 40, 60, 80 and 120 µm) on the time (week) until the occurrence of the predator (N. paspalivorus) in the refuge. Boxes span the 25–75 percentiles, whiskers indicate the range of the data without outliers, the central lines in the boxes represent the median values. Different letters above the boxes indicate significant differences (contrasts after Cox proportional hazards, p < 0.05)

The maximum height of the idiosoma of adult N. paspalivorus females is the most decisive measure for the ability to move beneath the perianth. This height depends critically on the physiological state of the female predators (Fig. 6, GLM: F3,156 = 104.8, p < 0.0001), with reproductive females being the largest and non-reproductive starved females being the smallest.

Effect of physiological condition on idiosoma height (µm) of N. paspalivorus. Shown are sizes of virgin non-reproducing (NR) females shortly after their last moult, virgin females starved for two days since their last moult (NRS), reproducing females (R) with full time access to food and reproducing females starved for two days (RS). Boxes span the 25–75 percentiles, whiskers indicate the range of the data and the central lines in the boxes represent the median values; N = 40 mites per physiological condition. Different letters above the boxes indicate significant differences (contrasts after GLM, p < 0.05)

Discussion

We show that sufficiently enlarging the perianth-rim-fruit distance (refuge entrance) resulted in the predators gaining earlier access to the area under the perianth, resulting in a decrease of densities of coconut mites. This provides experimental evidence that the size of the opening to the mite’s refuge may hamper the action of its potential predators, as was hypothesized in earlier work (Aratchige et al. 2007; Lawson-Balagbo et al. 2007b; Negloh et al. 2010; Lima et al. 2012).

In the control treatment, the natural increase of the refuge entrance allowed predators to reach the coconut mite colonies only ca. six weeks after the colonization by the pest (cf. Figs. 3, 4). By the time predatory mites were able to enter the area under the perianth, the coconut mites had already reached an average number of 2925 (SE 1660.0) mites per coconut fruit, sufficiently high densities to cause severe damage (Galvão et al. 2008).

The manipulation of the refuge entrances had no significant effect on the time of first occurrence of the coconut mite (Fig. 3), showing that the manipulation did not affect the timing and probability of infestation of the coconut fruit. The height of the worm-like body of coconut mites (35 µm, Lima et al. 2012) seems to be sufficiently small for it to be able to squeeze through the refuge entrance of an uninfested young coconut fruit (ca. two months old), measured as ca. 15–45 µm (Aratchige et al. 2007; Lima et al. 2012).

In contrast, the manipulation of the refuge entrance affected the occurrence of the predatory mite under the perianth. This can be explained by their larger size, although females of N. paspalivorus are flatter than any other known phytoseiid found on coconut plants (Fig. 6, F. da Silva, pers. obs.). Their soma height is at least 60 µm (Fig. 6), which makes them considerably larger than the refuge entrance of young coconut fruits. The results also show an effect of the physiological condition of the predatory mites: a female’s soma can double in height due to feeding and internal egg development. This means that only starved females and smaller life stages such as juveniles and males can enter the prey’s refuge. Once inside, they find themselves in a much larger space (so-called chamber, Aratchige et al. 2007; Lawson-Balagbo et al. 2007b) where adult females can increase in size when feeding and producing eggs. Increasing the opening to at least 60 µm made the refuges earlier accessible to the predators (Fig. 5). Thus, the difference in size between predators and prey relative to the size of the refuge entrance seems to be crucial for the success of biological control of this pest.

Counterintuitively, predatory mites were found on a smaller proportion of coconut fruits with an opening of 120 µm than on coconut fruits with openings of 60 and 80 µm (Fig. 2). Probably, earlier accessibility of the refuges with the largest entrances (Fig. 5) resulted in a shorter interaction period between predators and prey (Fig. 3). Therefore, predators probably had to disperse earlier from these coconut fruits in search for food, resulting in fewer fruits occupied by predators towards the end of the experiment.

It is clear that increasing the space between the perianth rim and the fruit surface improved control of the coconut mite by N. paspalivorus. However, it is unclear how our findings can be put to practice: we can hardly expect coconut growers to introduce small blades of PVC on every coconut fruit. Perhaps selective breeding for varieties with slightly larger refuge entrances would offer a long-term solution. We conclude that successful biological control of coconut mites critically hinges on the ability of predatory mites to enter the area under the perianth.

Even in the treatments with the largest openings, hence easier access for the predators, the densities of coconut mites were still sufficiently high to cause severe damage or even fruit abortion (Galvão et al. 2008). Obviously, control needs to be further improved, and different approaches could be adopted in attempting to achieve this goal. Although predators were present early in the experiment (Fig. 4, treatments with large refuge entrances), their numbers were low. A first way to increase the number of predators would be to supply them with alternative food when fruits are still young and the predators have no access to the area under the perianth. The resulting standing army of predators could then prevent establishment of the coconut mites.

Alternative food could conceivably be supplied in different ways, for example, by intercropping with plants that produce pollen or nectar or that harbour alternative prey, such as eriophyids, tarsonemids or other mite species. Pollen could also be added to young coconut bunches. Addition of alternative food to crops is a technique increasingly used in glasshouse production systems (van Rijn et al. 1999; Sabelis and van Rijn 2006; Leman and Messelink 2015; Janssen and Sabelis 2015). A second option could involve actions to facilitate the movement of predators among bunches within a tree and among trees. This could be done by connecting bunches of coconut fruits and coconut trees, for example with nets or sticks, reminiscent of a practice already used millenia ago by chinese farmers in citrus orchards (Leston 1973), by intercropping with climbing plants, or perhaps by reducing the planting distance among coconut trees so that their leaves will touch.

Other predatory mite species also occur in coconut fields and are more voracious predators of coconut mites than N. paspalivorus (Lawson-Balagbo et al. 2007a, 2008b; Domingos et al. 2009), but they occur only on older, heavily-damaged fruits (F. da Silva, pers. obs.). Probably, these predators cannot move under the tightly appressed inner perianth of younger damaged fruits. N. paspalivorus was by far the dominant predator species found in the experimental area and it was almost exclusively encountered under the perianths. Hence, selecting suitable predators for biological control should not only be based on predation rates and population growth rates, but should also consider important prey characteristics, such as its use of plant-provided refuges. In cases of biological control of sheltered pests, small predators may be the most adequate candidates.

References

Ambily P, Mathew TB (2003) Influence of arrangement of tepals bracts in coconut buttons on population of Aceria guerreronis. Insect Environ 9:172–173

Aratchige NS, Sabelis MW, Lesna I (2007) Plant structural changes due to herbivory: do changes in Aceria-infested coconut fruits allow predatory mites to move under the perianth? Exp Appl Acarol 43:97–107

Beattie AJ (1985) The evolutionary ecology of ant-plant mutualisms. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Charles JG, White V (1988) Airborne dispersal of Phytoseiulus persimilis (Acarina: Phytoseiidae) from a raspberry garden in New Zealand. Exp Appl Acarol 5:47–54

Crawley MJ (2007) The R book. Wiley, Chichester, England

Dicke M, Sabelis MW (1988) How plants obtain predatory mites as bodyguards. Neth J Zool 38:148–165

Domingos CA, Melo JWS, Gondim MGC, de Moraes GJ, Hanna R, Lawson-Balagbo LM, Schausberger P (2009) Diet-dependent life history, feeding preference and thermal requirements of the predatory mite Neoseiulus baraki (Acari: Phytoseiidae). Exp Appl Acarol 50:201–215

Fernando LCP, Aratchige NS, Peiris TSG (2003) Distribution patterns of coconut mite, Aceria guerreronis, and its predator Neoseiulus aff. paspalivorus in coconut palms. Exp Appl Acarol 31:71–78

Galvão AS, Gondim MGC, Michereff SJ (2008) Escala diagramática de dano de Aceria guerreronis Keifer (Acari: Eriophyidae) em coqueiro. Neotrop Entomol 37:723–728

Glas JJ, Schimmel BCJ, Alba JM, Escobar-Bravo R, Schuurink RC, Kant MR (2012) Plant glandular trichomes as targets for breeding or engineering of resistance to herbivores. Int J Mol Sci 13:17077–17103

Glas JJ, Alba JM, Simoni S, Villarroel CA, Stoops M, Schimmel BCJ, Schuurink RC, Sabelis MW, Kant MR (2014) Defense suppression benefits herbivores that have a monopoly on their feeding site but can backfire within natural communities. BMC Biol 12:1–14

Hothorn T, Bretz F, Westfall P (2008) Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biom J 50:346–363

Howard FW, Abreu-Rodriguez E (1991) Tightness of the perianth of coconuts in relation to infestation by coconut mites. Fla Entomol 74:358–362

Janssen A, Sabelis MW (2015) Alternative food and biological control by generalist predatory mites: the case of Amblyseius swirskii. Exp Appl Acarol 65:413–418

Janzen DH (1966) Coevolution of mutualism between ants and acacias in Central America. Evolution 20:249–275

Johnson DT, Croft BA (1976) Laboratory study of the dispersal behavior of Amblyseius fallacis (Acarina: Phytoseiidae). Ann Entomol Soc Am 69:1019–1023

Lawson-Balagbo LM, Gondim MGC, de Moraes GJ, Hanna R, Schausberger P (2007a) Life history of the predatory mites Neoseiulus paspalivorus and Proctolaelaps bickleyi, candidates for biological control of Aceria guerreronis. Exp Appl Acarol 43:49–51

Lawson-Balagbo LM, Gondim MGC, de Moraes GJ, Hanna R, Schausberger P (2007b) Refuge use by the coconut mite Aceria guerreronis: fine scale distribution and association with other mites under the perianth. Biol Control 43:102–110

Lawson-Balagbo LM, Gondim MGC, de Moraes GJ, Hanna R, Schausberger P (2008a) Exploration of the acarine fauna on coconut palm in Brazil with emphasis on Aceria guerreronis (Acari: Eriophyidae) and its natural enemies. Bull Entomol Res 98:83–96

Lawson-Balagbo LM, Gondim MGC, de Moraes GJ, Hanna R, Schausberger P (2008b) Compatibility of Neoseiulus paspalivorus and Proctolaelaps bickleyi, candidate biocontrol agents of the coconut mite Aceria guerreronis: spatial niche use and intraguild predation. Exp Appl Acarol 45:1–13

Leman A., Messelink G (2015) Supplemental food that supports both predator and pest: a risk for biological control? Exp Appl Acarol 65:511–524

Lesna I, Conijn CGM, Sabelis MW (2004) From biological control to biological insight: rust-mite induced change in bulb morphology, a new mode of indirect plant defence? Phytophaga 14:1–7

Lesna I, da Silva FR, Sato Y, Sabelis MW, Lommen ST (2014) Neoseiulus paspalivorus, a predator from coconut, as a candidate for controlling dry bulb mites infesting stored tulip bulbs. Exp App Acarol 63:189–204

Leston D (1973) The ant mosaic-tropical tree crops and the limiting of pests and diseases. Pest Artic News Summ 19:311–341

Lima DB, Melo JWS, Gondim MGC (2012) Limitations of Neoseiulus baraki and Proctolaelaps bickleyi as control agents of Aceria guerreronis. Exp Appl Acarol 56:233–246

Lindquist EE, Oldfield GN (1996) Evolution of eriophyoid mites in relation to their host-plants. In: Lindquist EE, Sabelis MW, Bruin J (eds) Eriophyoid mites: their biology, natural enemies and control, World Crop Pest Series. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 277–297

Lindquist EE, Sabelis MW, Bruin J (eds) (1996) Eriophyoid mites: their biology, natural enemies and control, World Crop Pest Series. Elsevier, Amsterdam

McMurtry JA, Croft BA (1997) Life-style of phytoseiid mites and their roles in biological control. Annu Rev Entomol 42:291–321

Magalhães S, van Rijn PC, Montserrat M, Pallini A, Sabelis MW (2007) Population dynamics of thrips prey and their mite predators in a refuge. Oecologia 150:557–568

Mariau D, Julia JF (1970) L'acariose à Aceria guerreronis (Keifer), ravageur du cocotier. Oleagineux 34:181–189

MATLAB and Statistics Toolbox (Release 2010a) The MathWorks Inc., Natick, Massachusetts, United States

Moore D, Alexander L (1987) Aspect of migration and colonization of the coconut palm by the coconut mite, Eriophyes guerreronis (Keifer) (Acari: Eriophyidae). Bull Entomol Res 77:641–650

Moore D, Howard FW (1996) Coconuts. In: Lindquist EE, Sabelis MW, Bruin J (eds) Eriophyoid mites: their biology, natural enemies and control, World Crop Pest Series. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 561–570

Navia D, Flechtmann CHW (2002) Mite (Arthropoda: Acari) associates of palms (Arecaceae) in Brazil: VI. New genera and new species of Eriophyidae and Phytoptidae (Prostigmata: Eriophyoidea). Int J Acarol 28:121–146

Navia D, de Moraes GJ, Lofego AC, Flechtmann CHW (2005) Acarofauna associada a frutos de coqueiro (Cocos nucifera L.) de algumas localidades das Américas. Neotrop Entomol 34:349–354

Negloh K, Hanna R, Schausberger P (2010) Season- and fruit age-dependent population dynamics of Aceria guerreronis and its associated predatory mite Neoseiulus paspalivorus on coconut in Benin. Biol Control 54:349–358

Negloh K, Hanna R, Schausberger P (2011) The coconut mite, Aceria guerreronis, in Benin and Tanzania: occurrence, damage and associated acarine fauna. Exp Appl Acarol 55:361–374

O’Dowd DJ, Willson MF (1989) Leaf domatia and mites on Australasian plants: ecological and evolutionary implications. Biol J Linn Soc 37:191–236

O’Dowd DJ (1994) Mite association with the leaf domatia of coffee (Coffea arabica) in north Queensland, Australia. Bull Entomol Res 84:361–366

Oldfield GN (1996) Diversity and host plant specificity. In: Lindquist EE, Sabelis MW, Bruin J (eds) Eriophyoid mites: their biology, natural enemies and control, Word Crop Pest Series. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 199–216

Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, R Core Team (2014) Nlme: linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme

Price PW, Bouton CE, Gross P, McPheron BA, Thompson JN, Weis AE (1980) Interactions among three trophic levels: influence of plants on interactions between insect herbivores and natural enemies. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 11:41–65

R Core Team (2013) R: a language and environment for statistical computing Vienna. http://www.R-project.org

Risch SJ, Rickson FR (1981) Mutualism in which ants must be present before plants produce food bodies. Nature 291:149–150

Sabelis MW, Afman BP (1994) Synomone-induced suppression of take-off in the phytoseiid mite, Phytoseiulus persimilis. Entomol Exp Appl 18:711–721

Sabelis MW, Bruin J (1996) Evolutionary ecology: life history patterns, food plant choice and dispersal. In: Lindquist EE, Sabelis MW, Bruin J (eds) Eriophyoid mites: their biology, natural enemies and control, Word Crop Pest Series. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 329–365

Sabelis MW, Janssen A, Bruin J, Bakker FM, Drukker B, Scutareanu P, van Rijn PC (1999) Interactions between arthropod predators and plants: a conspiracy against herbivorous arthropods? In: Bruin J, van der Geest LPS, Sabelis MW (eds) Ecology and Evolution of the Acari. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 207–229

Sabelis MW, Janssen A, Lesna I, Aratchige NS, Nomikou M, van Rijn PCJ (2008) Developments in the use of predatory mites for biological pest control. IOBC/WPRS Bull 32:187–200

Sabelis MW, Van Rijn PCJ (2006) When does alternative food promote biological pest control? IOBC/WPRS Bull 29:195–200

Siriwardena PH, Fernando LCP, Peiris TSG (2005) A new method to estimate the population size of coconut mite, Aceria guerreronis, on a coconut. Exp Appl Acarol 37:123–129

Therneau T (2014) A package for survival analysis in S. R package version 2.37-7. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survival

van Rijn PCJ, van Houten YM, Sabelis MW (1999) Pollen improves thrips control with predatory mites. IOBC/WPRS Bull 22:209–212

van Houten YM, Glas JJ, Hoogerbrugge H, Rothe J, Bolckmans KJF, Simoni S, van Arkel J, Alba JM, Kant MR, Sabelis MW (2013) Herbivory-associated degradation of tomato trichomes and its impact on biological control of Aculops lycopersici. Exp Appl Acarol 60:127–138

Wäckers FL, van Rijn PCJ, Bruin J (eds) (2005) Plant-provided food for carnivorous insects: a protective mutualism and its applications. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mr. W. Martinez for his handiness and essential contribution to the logistics in the field work in Venezuela. We also thank J. van Arkel (IBED, University of Amsterdam) taking the pictures of the mites, Zhongyu Lou (IvI, University of Amsterdam) for the assistance with the digital measurements of the images, and Ferry Bouman (IBED) for botanical advise. We are grateful to collaborators at the Universidad Centroccidental “Lisandro Alvarado”, ‘Instituto Nacional de Salud Agrícola Integral and the Government of Falcon State for logistics. Patrick De Clercq, Eric Wajnberg and two anonymous reviewers are thanked for constructive comments. FRdS was supported by the NWO-WOTRO Integrated Programme “Classical Biological Control of the Invasive Coconut Mite in Africa and Asia”) (The Hague, The Netherlands) and a prize of the Royal Academy of Sciences and Arts (Amsterdam, The Netherlands) to MWS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Handling Editor: Patrick De Clercq.

In memory of our co-author, mentor, teacher, colleague, partner and dear friend Maurice Sabelis, who sadly did not live to see the current version of this paper.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

da Silva, F.R., de Moraes, G.J., Lesna, I. et al. Size of predatory mites and refuge entrance determine success of biological control of the coconut mite. BioControl 61, 681–689 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10526-016-9751-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10526-016-9751-2