Abstract

The contribution of deficient telomerase activity to age-related decline in osteoblast functions and bone formation is poorly studied. We have previously demonstrated that telomerase over-expression led to enhanced osteoblast differentiation of human bone marrow skeletal (stromal) stem cells (hMSC) in vitro and in vivo. Here, we investigated the signaling pathways underlying the regulatory functions of telomerase in osteoblastic cells. Comparative microarray analysis and Western blot analysis of telomerase-over expressing hMSC (hMSC-TERT) versus primary hMSC revealed significant up-regulation of several components of insulin-like growth factor (IGF) signaling. Specifically, a significant increase in IGF-induced AKT phosphorylation and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity were observed in hMSC-TERT. Enhanced ALP activity was reduced in presence of IGF1 receptor inhibitor: picropodophyllin. In addition, telomerase deficiency caused significant reduction in IGF signaling proteins in osteoblastic cells cultured from telomerase deficient mice (Terc −/−). The low bone mass exhibited by Terc −/− mice was associated with significant reduction in serum levels of IGF1 and IGFBP3 as well as reduced skeletal mRNA expression of Igf1, Igf2, Igf2r, Igfbp5 and Igfbp6. IGF1-induced osteoblast differentiation was also impaired in Terc −/− MSC. In conclusion, our data demonstrate that impaired IGF/AKT signaling contributes to the observed decreased bone mass and bone formation exhibited by telomerase deficient osteoblastic cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteoblast dysfunction is the main determinant of age-related decline in bone formation and bone loss (Kassem and Marie 2011). Several extrinsic factors contribute to age-related impairment in osteoblastic functions such as age-related decline in the levels of trophic hormones e.g. estrogen, growth hormone or increased oxidative stress (Almeida et al. 2007; Ernst et al. 1989; Khosla and Riggs 2005; Kveiborg et al. 2000; Manolagas 2010; Boonen et al. 1999). On the other hand, cell intrinsic deficiency in telomerase activity leading to telomere shortening and cellular senescence contributes to organismal aging (Ye et al. 2014). There is increasing evidence that telomerase deficiency and telomere shortening contribute to the in vivo age-related impairment in bone formation. We have previously demonstrated that the telomerase deficient mice (Terc −/−) exhibited impaired in vivo osteoblastic bone formation and reduction in bone mass (Saeed et al. 2011) caused by cell autonomous impairment of osteoblastic cells of Terc −/− mice. On the other hand, telomerase activation either through pharmacological intervention (de Bernardes et al. 2011) or through gene therapy (de Bernardes et al. 2012) led to improvement in several age-related changes in mice including some increase in bone mass. At a cellular level, enhanced telomerase activity by over-expressing human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) gene in human bone marrow-derived stromal (skeletal) stem cells (hMSC) resulted in enhanced in vitro osteoblast differentiation and in vivo heterotopic bone formation (Abdallah et al. 2005; Simonsen et al. 2002).

Little is known about the regulatory mechanisms underlying the effects of telomerase activity and telomere length on osteoblast differentiation. Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) is one of the important bone anabolic factors. Skeletal IGF1 expression is reduced during aging and its levels are correlated with age-related reduction in bone mass (Liu et al. 2008; Yakar et al. 2002). The IGF system includes two ligands IGF1 and IGF2 interacting with IGF1 cognate receptor (IGFR1) and a number of IGF binding proteins (IGFBPs) (Conover 2008). IGF system has been demonstrated to regulate MSC proliferation (Langdahl et al. 1998) and osteoblast differentiation and functions (Xue et al. 2013). Several signaling pathways mediate the effects of IGFs on bone (Giustina et al. 2008). Among these, IGF1 induction of PI3K/AKT pathway is a principal regulator of osteoblast functions (Fujita et al. 2004; Levine et al. 2006; Raucci et al. 2008; Liu et al. 2007). PI3Ks are heterodimers consisting of two subunits, catalytic subunit p110 and regulatory unit p85. PI3Ks are activated by either receptor protein tyrosine kinase (RPTK) or G-protein coupled receptors (Fresno Vara et al. 2004). This activation results in the recruitment of several proteins with pleckstrin homology domain (PH) including PDK1 and AKT. The activation of AKT plays an important role in regulating osteoblast proliferation, differentiation and survival both in vitro and in vivo (Ghosh-Choudhury et al. 2002; Kawamura et al. 2007; Kawamura and Kawaguchi 2007; Mukherjee and Rotwein 2009). Interestingly, the effects of telomerase activity on several biological processes, such as, cell growth, cell cycle and apoptosis have been reported to be mediated via PI3K/AKT pathway (Xia et al. 2008; Kang et al. 1999). Also, AKT has been implicated in IGF1 driven telomerase activity in a multiple myeloma cell line (Akiyama et al. 2002).

In the present study, we examined whether IGF signaling mediates the biological effects of telomerase activity on osteoblastic cell differentiation and functions. We studied the effects of genetic gain and loss of telomerase functions in MSC on IGF/AKT expression and activation. We demonstrated that telomerase activation in MSC resulted in the up-regulation of IGF/IGFBPs system and IGF-induced AKT signaling. In addition, telomerase-deficiency-induced bone loss in mice was associated with reduced expression and serum levels of IGF and IGFBPs along with impaired IGF-induced AKT activation in MSC.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and reagents

Mouse bone marrow cells were isolated and cultured according to the protocol described by Peister et al. (Peister et al. 2004), with modifications (Post et al. 2008). Media was changed for every 3rd day. After 1–2 weeks, the cells were dissociated using Trypsin/EDTA for 4 min at 37 °C and plated according to the experimental setup.

Primary hMSCs were established from bone marrow aspirates obtained from iliac crest from healthy donors aged 25–30 years. Ethical approval was granted by the local Scientific Ethical Committee. Bone marrow mononuclear cells were isolated by low-density gradient centrifugation using Lymphoprep (Medinor, Copenhagen, Denmark) and hMSCs cultures were established by plastic adherence as described (Kassem et al. 1993).

Telomerase over-expressing human bone marrow stromal cell line known as hMSC-TERT has been established and characterized in our lab. The method of establishing hMSC-TERT and its characterization have been described in our previous publications (Abdallah et al. 2005; Simonsen et al. 2002).

IGF-1R Inhibitor, Picropodophyllin (PPP) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc, (Heidelberg, Germany).

DNA microarray analysis

Both primary hMSCs and hMSC-TERT cells were cultured in triplicate at 3 × 104 cells/cm2 in petri dishes in standard growth medium. When they were 90–100 % confluent, total cellular RNA was isolated from each of three independent cultures using an RNeasy Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. First- and second-strand cDNA synthesis was performed from 8 µg total RNA using the SuperScript Choice System (Life-Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Subsequent hybridization and scanning of the Affymetrix GeneChip arrays were performed as described previously (Tsugawa et al. 2003a). The biotinylated targets were hybridized to human U133 Plus 2.0 Array Affymetrix GeneChip oligonucleotide arrays. Expression measures were generated and normalized using the RMA procedure (Irizarry et al. 2003; Shie et al. 2012), implemented in the Bioconductor package (www.bioconductor.org/). Data was analyzed using Ingenuity Pathway analysis knowledge base system (Ingenuity® Systems, www.ingenuity.com). Signaling pathways known to play an important role in osteoblast commitment, proliferation, differentiation and function were identified among pathways that are differentially up or down regulated in comparison to control (minimum value = 2 fold).

Mice breeding, genotyping and handling

Terc deficient mice (Terc −/− Strain-004132) were purchased from Jackson laboratory (Maine, USA) and kept in a pathogen-free environment on standard chow. Terc −/− mice were inter-crossed to generate 3rd generation Terc −/− (Terc −/−-G3) mice, and were maintained in a C57BL/6J background. Wild type (WT) mice were employed as controls. Genotyping was performed according to the protocol recommended by Jackson laboratory (Saeed et al. 2011).

Serum IGFs and IGFBPs measurements

Blood samples were collected from WT and Terc −/− mice (n = 5) and serum was collected and frozen down at −80 °C. Serum IGF1 level was measured by RIA using a polyclonal rabbit antibody (Nichols Institute Diagnostics, San Capistrano, CA) and recombinant human IGF1 as standard (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK). Monoiodinated IGF1 (125I-labeled [Tyr31] IGF1) was obtained from Novo-Nordisk (Bagsvaerd, Denmark). Serum IGFBPs were measured by Western ligand blotting assay as described previously (Abdallah et al. 2007; Flyvbjerg et al. 1992).

RNA isolation and quantitative real time PCR

RNA was isolated from long bones and cultured cells using Trizol® method according to the manufacture’s protocol.

cDNA was synthesized from 2 μg of total RNA using a commercial revertAid H minus first strand cDNA synthesis kit (Fermentas, Helsingborg, Sweden), according to the manual’s instructions.

Gene expression was determined by quantitative real-time PCR (RT-PCR), performed in an iCycler IQ detection system (Bio-Rad, Herlev, Denmark), using IQ SYBR Green as a double strand DNA-specific fluorescent binding dye. RT-PCR was performed in a final volume of 20 μl, containing 3 μl cDNA (diluted 1:20), 20 pmol of each primer and 10 μl of IQ SYBR® Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Herlev, Denmark) according to the manual’s instruction. Expression level for each target gene was calculated using a comparative Ct method [(1/(2∆Ct) formula and data were represented as relative expression to Actin reference gene. Data were analysed using Microsoft Excel 2000 to generate relative expression values.

Osteoblast differentiation

MSCs were plated at 20 × 103 cells/cm2 in 24 well plates and induced to differentiate into osteoblasts in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium (IMDM; GIBCO, Cat. No. 21980) containing 12 % FBS (FBS; GIBCO), 100 U/ml penicillin (GIBCO), 100 µg/ml streptomycin (GIBCO) and 12 µM l-glutamine (GIBCO, Cat. No. 25030) supplemented with 10 nM dexamethasone (Sigma), 10 mM β—glycerol-phosphate (Sigma), 50 µg/ml Vitamin C (Sigma) and 10 ng/ml IGF-1. Media were changed every 3rd day until day 10.

Cytochemical staining

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) enzymatic staining

Cells were fixed with acetone/citrate buffer pH 4.2 (1.5:1) for 5 min at room temperature and stained with Napthol-AS-TR-phosphate solution for 1 h at room temperature. Napthol-AS-TR-phosphate solution consists of Napthol-AS-TR-phosphate (Sigma) diluted 1:5 in H2O and Fast Red TR (Sigma) diluted 1:1.2 in 0.1 M Tris buffer (OUH pharmacy), pH 9.0, after which both solutions were mixed 1:1. Cells were counterstained with Mayers-Hematoxylin for 5 min at room temperature.

Alkaline phosphatase activity assay

ALP activity was measured by using p-nitrophenyl phosphate (Fluka, Denmark) as substrate—normalized against the cell number as described previously (Qiu et al. 2010). Briefly, cell number was quantitated by adding CellTiter-Blue reagent (Promega) to culture medium, incubating at 37 °C for 1 h and measuring fluorescent intensity (560EX/590EM). Thereafter, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and Tris-buffered saline, fixed in 3.7 % formaldehyde, 90 % ethanol for 30 s at room temperature, incubated with substrate (1 mg/ml of p-nitrophenyl phosphate in 50 mm NaHCO3, pH 9.6, and 1 mm MgCl2) at 37 °C for 20 min, and the absorbance was measured at 405 nm.

Western blot analysis

Cells were treated for short term with IGF-1 recombinant protein (R&D, systems) and collected at different time points post treatment—washed in PBS before adding cell lysis buffer (10 mm Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm sodium chloride, 1 % Nonidet P-40, 0.1 % SDS, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mm NaF, 1 mm Na3VO4), supplemented by protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). 30 µg of protein was size fractionated using SDS-PAGE (Invitrogen, Denmark) and electroblotted onto Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore, Denmark). Blots were blocked by 5 % milk powder in Tris-buffered saline (TBS, pH 8.0) for 1 h. Antibodies (total or phosphor) specific for AKT (Ser-473), PTEN (Ser380/Ther382/383), p85, PDK1 (Ser-2448) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Leiden, Netherlands).

Primary antibody (1:1000) incubations were performed in 5 % milk powder TBST (TBS containing 0.1 % Tween 20) overnight followed by incubation with secondary antibody (1:1000) with horseradish peroxidase for 2 h conjugated. Proteins were visualized with the ECL system (Amersham bioscience, UK).

Western blot band area/intensity was measured as described previously (Tsugawa et al. 2003b). Bands area/intensity for AKT, PDK1 and alpha-tubulin were measured using Image J (Wayne Rasband, NIH, http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij) software (Chapman et al. 2006).

Statistical analysis

Statistical tests were performed using Microsoft Excel® and Graphpad5 (Prism®). Pairwise comparisons were performed using student t test. An alpha value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Telomerase activation in human MSC enhanced IGF and PI3K/AKT signaling

We have previously shown that increased telomerase activity in hMSC by stable over-expression of hTERT in hMSC-TERT cell line, resulted in enhanced cell proliferation and in vivo heterotopic bone formation (Abdallah et al. 2005; Simonsen et al. 2002). To identify signaling pathways mediating the stimulatory effect of telomeraization on hMSCs biology, we compared the molecular signature of primary hMSC where telomerase activity is absent (Simonsen et al. 2002) and hMSC-TERT cells using Affymetrix DNA micro-arrays (unpublished data). Ingenuity® pathway analysis of differentially up-regulated genes by hMSC-TERT revealed significant enrichment of components of IGF signaling (Sos2, Pik3c2A, Akt3, Pik3c3, Igfbp4 and Igfbp2) and PI3 K/AKT signaling (Akt3, Pik3r1, Pik3cA, Sos2, Itga4 and Eif4E) (Fig. 1a(ii), B-C, 1SB).

Enhanced telomerase activity in human marrow stromal cells (hMSC) Stimulates IGF/PI3K/AKT Signaling. Microarray analysis was performed for hMSC-TERT and primary isolated hMSC at baseline as described in the Materials and Methods. a. (i) Gene ontology of significantly expressed genes in hMSC-TERT in comparison to primary hMSC. (ii) Significantly up-regulated signaling pathways as revealed by Ingenuity® pathway analysis in hMSC-TERT versus hMSC. b Components of IGF signaling pathway that are differentially induced by telomerase activation in hMSC. c Components of PI3K/AKT signaling that are differentially induced by telomerase activation in hMSC. Black bars represent up-regulated while white bars represent down-regulated pathways in hMSC-TERT versus hMSC. p values obtained by Fisher’s exact test and presented as—log

Enhanced telomerase activity in hMSC increased PI3K/AKT signaling and AKT phosphorylation

A number of studies have shown that AKT activation promotes cell proliferation, survival and differentiation in osteoblasts (Ghosh-Choudhury et al. 2002; Kawamura et al. 2007; Kawamura and Kawaguchi 2007; Mukherjee and Rotwein, 2009). To verify the activation of IGF signaling pathway by telomerase activity, we studied the activation of IGF downstream target proteins in hMSC-TERT versus primary hMSCs. As shown in Fig. 2a, Western blot analysis revealed a significant up-regulation of IGF-induced AKT phosphorylation in hMSC-TERT as compared to primary hMSCs. A significant up-regulation of p-PDK1 after 10 min of IGF1 stimulation was also observed (Fig. 2a). On the other hand, no detectable significant changes were observed in PTEN protein levels (Fig. 2a). IGF-induced osteoblast differentiation was significantly enhanced in hMSC-TERT compared to primary hMSC as assessed by increased alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity measurements (Fig. 2b). To ensure that the effect on osteoblast differentiation was specific for IGF signaling, we examined the effect of specific IGF1R inhibitor picropodophyllin (PPP) on IGF-induced ALP activity in both primary hMSCs and hMSC-TERT cells. As shown in Fig. 2c, treatment with PPP led to a dose-dependent inhibition of IGF-induced ALP activity with more pronounced effect in hMSC-TERT than primary hMSC.

Enhanced telomerase activity in hMSC promotes IGF-induced osteoblast differentiation and activation of AKT signaling. a Enhanced telomerase activity in hMSC-TERT increased AKT phosphorylation following IGF1 treatment. Western blot analysis of phosphorylated and total proteins of AKT, PTEN and PDK1 following 5, 10 and 20 min of IGF1 treatment (10 ng/ml). Quantification analysis of WB was performed by ImageJ. b Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity normalized for cell number in primary hMSC and hMSC-TERT following treatment with IGF1 (dose range 1–100 ng/ml). c Primary hMSC and hMSC-TERT were treated with IGF1 (100 ng/ml) in the absence or the presence of IGF1R specific inhibitor (PPP). After 6 days of induction, ALP activity was measured and normalized to cell number per each treatment condition. Data are mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01

Telomerase deficient mice exhibited changes in serum levels of IGF and its binding proteins (IGFBPs)

IGF1/IGFBP3 axis has been reported to regulate bone growth and bone mass (Schmid et al. 1991; Yakar et al. 2002). Likewise, reduced serum levels of IGF1 and IGFBP3 have been implicated in the pathogenesis of age-related osteoporosis (Sugimoto et al. 1997). To study the effect of loss of telomerase activity on IGF system, we measured serum levels of IGF1 and its binding proteins (IGFBPs) in Terc −/− mice and WT controls. As shown in Fig. 3a, serum IGF1 and IGFBP3 were significantly decreased in Terc −/− mice. Since production of IGFs in local tissue microenvironment plays important role in bone biology (Sjogren et al. 1999), we also measured mRNA expression of Igf1, Igf2 and Igfbp1, Igfbp5, Igfbp6 in bone matrix. We found that their expression was significantly reduced in the bone matrix of Terc −/− mice (Fig. 3b).

Telomerase deficiency in mice is associated with changes in levels of IGFs and IGFBPs. a Serum levels of IGF-1 and IGFBPs (IGFBP1-4) in telomerase deficient mice Terc −/− and wild type controls. b Gene expression of Igfs (Igf-1, Igf-2, Igf-1r and Igf-2r) and Igfbps ((IGFBP1-6) in Terc −/− tibia compared to WT controls. Each target gene was normalized to b-actin and represented as fold change over WT controls. Data are mean ± SD. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01. (n = 5)

Terc −/− mMSCs exhibits defective IGF signaling

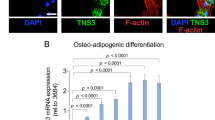

We next examined gene expression profiles of Igf/Igfbp system in murine MSC (mMSC) cultured from bone marrow samples obtained from Terc −/− and WT control mice. At baseline, Terc −/− mMSCs exhibited reduced mRNA expression of Igf1, Igf2, Igf1receptor (Igf1r) and higher expression of Igfbp1, Igfbp2, Igfbp4 and Igfbp6 as compared to WT mMSC (Fig. 4a). Following in vitro osteoblast differentiation in the presence of IGF1, the Terc −/− MSCs exhibited impaired osteoblast differentiation in response to IGF treatment as observed by reduced staining for ALP (Fig. 4b) and reduced expression levels of Igf1, Igf2, Igf1r, Igfbp1 and Igfbp6, while, expression of Igf2r, Igfbp4 and Igfbp5 were increased (Fig. 4c).

Inhibition of IGF1-induced osteoblast differentiation in telomerase deficient murine marrow stromal cells (mMSCs). a Real time PCR gene expression analysis of Igf1, Igf2, Igf1r, Igf2r, Igfbp1, Igfbp2, Igfbp4, Igfbp5 and Igfbp6 in Terc −/− mMSCs versus WT mMSCs at baseline. Each target gene was normalized to b-actin and represented as fold change over WT mMSCs. B.Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) staining at day 5 (upper panel) and at day 10 (lower panel) following IGF-1 induced osteoblast differentiation in Terc −/− mMSCs versus WT mMSCs. C. Real time PCR analysis of Igfs, IGF receptors (IGFr) and IGF binding proteins (IGFBPs) expression after 7 days of IGF-1 induction in Terc −/− mMSCs versus WT mMSC. Each target gene was normalized to b-actin and represented as fold change over control non-induced cells. Data are mean ± SD. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01. (n = 3)

To study the mechanism underlying the impairment of IGF-induced osteoblast differentiation in Terc −/− mMSCs, we treated WT mMSCs with IGF (10 ng/ml) that resulted in increased levels of P-AKT and its downstream target P-PDK1 (Fig. 5a). In contrast IGF-induced AKT phosphorylation was absent in Terc −/− mMSCs (Fig. 5a). No detectable differences in total PTEN and P-PTEN were observed between Terc −/− MSCs and WT-MSCs following IGF1 stimulation (Fig. 5a).

Impaired IGF1-induced AKT phosphorylation in telomerase deficient murine marrow stromal cells (mMSCs). a Reduced AKT and PDK1 phosphorylation following IGF1 (10 ng/mL) treatment of Terc −/− mMSCs versus WT mMSCs. Western blot analysis of phosphorylated and total p85, PTEN, PDK1 and AKT as well as loading control α-Tubulin following 10 and 20 min of IGF1stimulation. Data are generated from pooled protein samples from three independent experiments of IGF1–stimulated Terc −/− mMSCs versus WT mMSC. Quantification analysis of WB was performed by ImageJ. Data are mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01

Discussion

In the present study, we identified IGF signaling as a downstream target of telomerase activity in skeletal stem cells (MSC). Mice lacking telomerase activity exhibited impaired osteoblastic functions and low bone mass that were associated with reduction in IGF1/IGFBP3 serum levels and impairment of IGF/AKT signaling in MSCs. Our data suggest a link between the absence of telomerase activity and the impairment of IGF signaling in MSC as a contributing factor for age-related reduced osteoblast function and bone formation.

We have previously demonstrated, in a number of gain and loss of function studies, an association between telomerase activity, telomere length and skeletal tissue homeostasis (Abdallah et al. 2005; Simonsen et al. 2002; Saeed et al. 2011). Over-expression of telomerase in hMSC not only extended their life span but also enhanced their in vivo heterotopic bone formation capacity (Simonsen et al. 2002). Telomerase deficiency in Terc −/− mice resulted in age-related reduction in bone mass caused by defective osteoblast differentiation and creation of pro-inflammatory bone marrow micro-environment favoring osteoclast formation (Saeed et al. 2011). However, the target of telomerase activity in MSCs is not known.

We observed up-regulation of IGF-related genes including AKT phosphorylation in response to increased telomerase activity in hMSC suggesting the involvement of IGF/AKT signaling pathway in mediating the telomerase functional effects. The association between telomerase activity and PI3 K/AKT signaling pathway has previously been reported in a number of cellular models including growth hormone dependent telomerase activation via PI3 K signaling in Chinese hamster ovary cells (Gomez-Garcia et al. 2005). Also, transcriptional activation of hTERT in human T cell leukemia—lymphoma virus-1 infected cells was mediated by PI3K (Bellon and Nicot 2008) and PI3K/AKT-dependent activation of hTERT was reported to be accomplished by ectopic expression of EGFR in oral squamous epithelial cells (Heeg et al. 2011). Finally, increased telomerase activity in natural killer cells after IL2 stimulus took place via PI3K/AKT signaling (Kawauchi et al. 2005). Interestingly, a number of studies have shown that PI3K/AKT signaling pathway regulates hTERT activity (Breitschopf et al. 2001; Haendeler et al. 2003; Kang et al. 1999). Thus, it is plausible that telomerase activity is regulated by PI3K/AKT signaling via a feedback mechanism during bone formation that requires recruitment and proliferation of MSC at bone formation sites.

We observed that serum levels of IGF1 and IGFBP3 were reduced in telomerase deficient mice Several human studies have reported an association between decreased serum IGF1 and age-related reduction in bone mass and bone strength (Barrett-Connor and Goodman-Gruen 1998; Langlois et al. 1998; Yamaguchi et al. 2006; Garnero et al. 2000; Ohlsson et al. 2011; Rosen et al. 1997). It has also been reported that IGF1 production in bone microenvironment is more relevant to skeletal maintenance than circulating IGF1 (Ohlsson et al. 2011; Yakar et al. 2002). Our finding of the presence of low levels of gene expression of IGF system within bone matrix in telomerase deficient murine MSC corroborate the contribution of local IGF system to impaired bone formation during aging. On the other hand, mutant mice exhibiting reduced GH/IGF1/insulin secretions exhibit extended life span (Brown-Borg et al. 1996; Kurosu et al. 2005). However, bone mass has not been directly measured in these mice.

The role of IGF1 in cellular senescence is not completely understood. Similar to our findings, age-related decline in IGF1 and IGFBP3 has been reported in mice and rats (Severgnini et al. 1999; Xian et al. 2012). Also, a recent study employing aged mice reported that activation of cellular telomerase activity delayed many aspects of age-related phenotypes and improved longevity which was associated with increased serum IGF1 levels (de Bernardes et al. 2012). The role of IGF1 in bone biology has been demonstrated in IGF1-deficient mice that exhibited skeletal malformation, delayed mineralization, decreased chondrocyte proliferation and increased chondrocyte apoptosis (Laviola et al. 2008). In human conditions of bone loss, IGF1 action and signaling is impaired in osteoblastic cells (Perrini et al. 2010). Likewise, reduction in IGF1 levels has been reported in age related bone loss, both men and women (Boonen et al. 1999; Nicolas et al. 1994; Rosen et al. 1998; Rosen 2004; Seck et al. 2001). Administration of recombinant human IGF1 has been associated with improved osteoblast functions in healthy females exhibiting decreased bone turnover due to caloric restrictions (Grinspoon et al. 1996). Interestingly, PI3 K/AKT signaling is utilized by IGF1 to reduce osteoblast apoptosis (Grey et al. 2003). Comparative analysis of IGF signaling in human osteoblast cultures established from healthy donors and osteoporotic patients revealed that IGFR1 and components of IGF1 downstream signaling were not responsive to IGF1 stimulation in osteoporotic cells due to reduced phosphorylation of AKT at Ser-473 and Thr-308 (Perrini et al. 2008). Furthermore, data from IGF1 conditional gain and loss of function studies in mice employing osteoblast specific gene promoters, such as Col1a1 and Col1a2, respectively, suggest that IGF1 gain of function resulted in increase length of long bones and cortical width in mice while loss of function resulted in decrease bone formation and bone mass (Jiang et al. 2006). Similarly, Xian et al., demonstrated that IGF1 stimulation activates mTOR via PI3K/AKT pathway in Sca1+mMSCs and conditioned media containing IGF1 released from bone matrix significantly enhanced osteoblast differentiation and increased phosphorylation of PI3K, AKT and mTOR (Xian et al. 2012), implicating PI3K/AKT signaling in mediating IGF1 effects on bone. Thus, the ability of IGF1 to rescue aspects of age-related phenotype requires further investigation.

In addition to changes in IGF1, we observed that the levels of telomerase activity in MSC affected several IGFBPs gene expression and serum levels. The bioactivity of IGF1 is regulated by several IGF binding proteins (IGFBPs) which mainly modulate IGF1 bioavailability to IGF receptors (Muck et al. 2008). IGFBP3 is an abundant protein in human serum and binds over 90 % of circulating IGF1 resulting in prolonged half-life of IGF1 (Baxter and Martin 1989) and the resulting IGF1/IGFBP3 complex exerts tissue and cell type specific effects (Baege et al. 2004). IGFBP3 has been shown to inhibit cell growth by interfering with IGF1 interaction with its cognate receptor (Kelley et al. 1996). IGFBP3 has also IGF1-indpenent effects on cell growth (Firth and Baxter 2002). Increased expression of IGFBP3 has been reported in senescent cells (Baege et al. 2004; Muck et al. 2008) and has been proposed as a marker of cellular senescence (Baege et al. 2004). Additionally, we also observed increased in serum levels of IGFBP4 which is an inhibitory IGFBP (Kassem et al. 1996). Thus, it is possible that the net effects are decreased serum IGF1 bioactivity.

Conclusion

Our data suggest that telomerase activity regulates IGF1 dependent PI3K/AKT signaling and that age-related deficiency in telomerase activity in osteoblastic cells contributes to age-related decreased bone formation. Modulating osteoblastic cells telomerase enzyme or IGF signaling activity pharmacologically is a possible strategy for prevention of age related bone loss.

References

Abdallah BM, Haack-Sorensen M, Burns JS, Elsnab B, Jakob F, Hokland P, Kassem M (2005) Maintenance of differentiation potential of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells immortalized by human telomerase reverse transcriptase gene despite [corrected] extensive proliferation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 326:527–538

Abdallah BM, Ding M, Jensen CH, Ditzel N, Flyvbjerg A, Jensen TG, Dagnaes-Hansen F, Gasser JA, Kassem M (2007) Dlk1/FA1 is a novel endocrine regulator of bone and fat mass and its serum level is modulated by growth hormone. Endocrinology 148:3111–3121

Akiyama M, Hideshima T, Hayashi T, Tai YT, Mitsiades CS, Mitsiades N, Chauhan D, Richardson P, Munshi NC, Anderson KC (2002) Cytokines modulate telomerase activity in a human multiple myeloma cell line. Cancer Res 62:3876–3882

Almeida M, Han L, Martin-Millan M, O’Brien CA, Manolagas SC (2007) Oxidative stress antagonizes Wnt signaling in osteoblast precursors by diverting beta-catenin from T cell factor- to forkhead box O-mediated transcription. J Biol Chem 282:27298–27305

Baege AC, Disbrow GL, Schlegel R (2004) IGFBP-3, a marker of cellular senescence, is overexpressed in human papillomavirus-immortalized cervical cells and enhances IGF-1-induced mitogenesis. J Virol 78:5720–5727

Barrett-Connor E, Goodman-Gruen D (1998) Gender differences in insulin-like growth factor and bone mineral density association in old age: the Rancho Bernardo study. J Bone Miner Res 13:1343–1349

Baxter RC, Martin JL (1989) Binding proteins for the insulin-like growth factors: structure, regulation and function. Prog Growth Factor Res 1:49–68

Bellon M, Nicot C (2008) Central role of PI3K in transcriptional activation of hTERT in HTLV-I-infected cells. Blood 112:2946–2955

Boonen S, Mohan S, Dequeker J, Aerssens J, Vanderschueren D, Verbeke G, Broos P, Bouillon R, Baylink DJ (1999) Down-regulation of the serum stimulatory components of the insulin-like growth factor (IGF) system (IGF-I, IGF-II, IGF binding protein [BP]-3, and IGFBP-5) in age-related (type II) femoral neck osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 14:2150–2158

Breitschopf K, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S (2001) Pro-atherogenic factors induce telomerase inactivation in endothelial cells through an Akt-dependent mechanism. FEBS Lett 493:21–25

Brown-Borg HM, Borg KE, Meliska CJ, Bartke A (1996) Dwarf mice and the ageing process. Nature 384:33

Chapman MD, Keir G, Petzold A, Thompson EJ (2006) Measurement of high affinity antibodies on antigen-immunoblots. J Immunol Methods 310:62–66

Conover CA (2008) Insulin-like growth factor-binding proteins and bone metabolism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 294:E10–E14

de Bernardes JB, Schneeberger K, Vera E, Tejera A, Harley CB, Blasco MA (2011) The telomerase activator TA-65 elongates short telomeres and increases health span of adult/old mice without increasing cancer incidence. Aging Cell 10:604–621

de Bernardes JB, Vera E, Schneeberger K, Tejera AM, Ayuso E, Bosch F, Blasco MA (2012) Telomerase gene therapy in adult and old mice delays aging and increases longevity without increasing cancer. EMBO Mol Med 4:691–704

Ernst M, Heath JK, Rodan GA (1989) Estradiol effects on proliferation, messenger ribonucleic acid for collagen and insulin-like growth factor-I, and parathyroid hormone-stimulated adenylate cyclase activity in osteoblastic cells from calvariae and long bones. Endocrinology 125:825–833

Firth SM, Baxter RC (2002) Cellular actions of the insulin-like growth factor binding proteins. Endocr Rev 23:824–854

Flyvbjerg A, Kessler U, Dorka B, Funk B, Orskov H, Kiess W (1992) Transient increase in renal insulin-like growth factor binding proteins during initial kidney hypertrophy in experimental diabetes in rats. Diabetologia 35:589–593

Fresno Vara JA, Casado E, De CJ, Cejas P, Belda-Iniesta C, Gonzalez-Baron M (2004) PI3K/Akt signalling pathway and cancer. Cancer Treat Rev 30:193–204

Fujita T, Azuma Y, Fukuyama R, Hattori Y, Yoshida C, Koida M, Ogita K, Komori T (2004) Runx2 induces osteoblast and chondrocyte differentiation and enhances their migration by coupling with PI3K-Akt signaling. J Cell Biol 166:85–95

Garnero P, Sornay-Rendu E, Claustrat B, Delmas PD (2000) Biochemical markers of bone turnover, endogenous hormones and the risk of fractures in postmenopausal women: the OFELY study. J Bone Miner Res 15:1526–1536

Ghosh-Choudhury N, Abboud SL, Nishimura R, Celeste A, Mahimainathan L, Choudhury GG (2002) Requirement of BMP-2-induced phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Akt serine/threonine kinase in osteoblast differentiation and Smad-dependent BMP-2 gene transcription. J Biol Chem 277:33361–33368

Giustina A, Mazziotti G, Canalis E (2008) Growth hormone, insulin-like growth factors, and the skeleton. Endocr Rev 29:535–559

Gomez-Garcia L, Sanchez FM, Vallejo-Cremades MT, de Segura IA, del Campo EM (2005) Direct activation of telomerase by GH via phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase. J Endocrinol 185:421–428

Grey A, Chen Q, Xu X, Callon K, Cornish J (2003) Parallel phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase and p42/44 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways subserve the mitogenic and antiapoptotic actions of insulin-like growth factor I in osteoblastic cells. Endocrinology 144:4886–4893

Grinspoon S, Baum H, Lee K, Anderson E, Herzog D, Klibanski A (1996) Effects of short-term recombinant human insulin-like growth factor I administration on bone turnover in osteopenic women with anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 81:3864–3870

Haendeler J, Hoffmann J, Rahman S, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S (2003) Regulation of telomerase activity and anti-apoptotic function by protein-protein interaction and phosphorylation. FEBS Lett 536:180–186

Heeg S, Hirt N, Queisser A, Schmieg H, Thaler M, Kunert H, Quante M, Goessel G, von Werder A, Harder J, Beijersbergen R, Blum HE, Nakagawa H, Opitz OG (2011) EGFR overexpression induces activation of telomerase via PI3 K/AKT-mediated phosphorylation and transcriptional regulation through Hif1-alpha in a cellular model of oral-esophageal carcinogenesis. Cancer Sci 102:351–360

Irizarry RA, Bolstad BM, Collin F, Cope LM, Hobbs B, Speed TP (2003) Summaries of Affymetrix GeneChip probe level data. Nucleic Acids Res 31:e15

Jiang J, Lichtler AC, Gronowicz GA, Adams DJ, Clark SH, Rosen CJ, Kream BE (2006) Transgenic mice with osteoblast-targeted insulin-like growth factor-I show increased bone remodeling. Bone 39:494–504

Kang SS, Kwon T, Kwon DY, Do SI (1999) Akt protein kinase enhances human telomerase activity through phosphorylation of telomerase reverse transcriptase subunit. J Biol Chem 274:13085–13090

Kassem M, Marie PJ (2011) Senescence-associated intrinsic mechanisms of osteoblast dysfunctions. Aging Cell 10:191–197

Kassem M, Mosekilde L, Eriksen EF (1993) 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 potentiates fluoride-stimulated collagen type I production in cultures of human bone marrow stromal osteoblast-like cells. J Bone Miner Res 8:1453–1458

Kassem M, Okazaki R, De LD, Harris SA, Robinson JA, Spelsberg TC, Conover CA, Riggs BL (1996) Potential mechanism of estrogen-mediated decrease in bone formation: estrogen increases production of inhibitory insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-4. Proc Assoc Am Physicians 108:155–164

Kawamura N, Kawaguchi H (2007) Regulation of bone mass by PI3 kinase/Akt signaling. Nihon Rinsho 65(Suppl 9):67–70

Kawamura N, Kugimiya F, Oshima Y, Ohba S, Ikeda T, Saito T, Shinoda Y, Kawasaki Y, Ogata N, Hoshi K, Akiyama T, Chen WS, Hay N, Tobe K, Kadowaki T, Azuma Y, Tanaka S, Nakamura K, Chung UI, Kawaguchi H (2007) Akt1 in osteoblasts and osteoclasts controls bone remodeling. PLoS ONE 2:e1058

Kawauchi K, Ihjima K, Yamada O (2005) IL-2 increases human telomerase reverse transcriptase activity transcriptionally and posttranslationally through phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase/Akt, heat shock protein 90, and mammalian target of rapamycin in transformed NK cells. J Immunol 174:5261–5269

Kelley KM, Oh Y, Gargosky SE, Gucev Z, Matsumoto T, Hwa V, Ng L, Simpson DM, Rosenfeld RG (1996) Insulin-like growth factor-binding proteins (IGFBPs) and their regulatory dynamics. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 28:619–637

Khosla S, Riggs BL (2005) Pathophysiology of age-related bone loss and osteoporosis. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 34:1015–1030 xi

Kurosu H, Yamamoto M, Clark JD, Pastor JV, Nandi A, Gurnani P, McGuinness OP, Chikuda H, Yamaguchi M, Kawaguchi H, Shimomura I, Takayama Y, Herz J, Kahn CR, Rosenblatt KP, Kuro-o M (2005) Suppression of aging in mice by the hormone Klotho. Science 309:1829–1833

Kveiborg M, Flyvbjerg A, Rattan SI, Kassem M (2000) Changes in the insulin-like growth factor-system may contribute to in vitro age-related impaired osteoblast functions. Exp Gerontol 35:1061–1074

Langdahl BL, Kassem M, Moller MK, Eriksen EF (1998) The effects of IGF-I and IGF-II on proliferation and differentiation of human osteoblasts and interactions with growth hormone. Eur J Clin Invest 28:176–183

Langlois JA, Rosen CJ, Visser M, Hannan MT, Harris T, Wilson PW, Kiel DP (1998) Association between insulin-like growth factor I and bone mineral density in older women and men: the Framingham Heart study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83:4257–4262

Laviola L, Natalicchio A, Perrini S, Giorgino F (2008) Abnormalities of IGF-I signaling in the pathogenesis of diseases of the bone, brain, and fetoplacental unit in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 295:E991–E999

Levine AJ, Feng Z, Mak TW, You H, Jin S (2006) Coordination and communication between the p53 and IGF-1-AKT-TOR signal transduction pathways. Genes Dev 20:267–275

Liu X, Bruxvoort KJ, Zylstra CR, Liu J, Cichowski R, Faugere MC, Bouxsein ML, Wan C, Williams BO, Clemens TL (2007) Lifelong accumulation of bone in mice lacking Pten in osteoblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:2259–2264

Liu JM, Zhao HY, Ning G, Chen Y, Zhang LZ, Sun LH, Zhao YJ, Xu MY, Chen JL (2008) IGF-1 as an early marker for low bone mass or osteoporosis in premenopausal and postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Metab 26:159–164

Manolagas SC (2010) From estrogen-centric to aging and oxidative stress: a revised perspective of the pathogenesis of osteoporosis. Endocr Rev 31:266–300

Muck C, Micutkova L, Zwerschke W, Jansen-Durr P (2008) Role of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 in human umbilical vein endothelial cell senescence. Rejuvenation Res 11:449–453

Mukherjee A, Rotwein P (2009) Akt promotes BMP2-mediated osteoblast differentiation and bone development. J Cell Sci 122:716–726

Nicolas V, Prewett A, Bettica P, Mohan S, Finkelman RD, Baylink DJ, Farley JR (1994) Age-related decreases in insulin-like growth factor-I and transforming growth factor-beta in femoral cortical bone from both men and women: implications for bone loss with aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 78:1011–1016

Ohlsson C, Mellstrom D, Carlzon D, Orwoll E, Ljunggren O, Karlsson MK, Vandenput L (2011) Older men with low serum IGF-1 have an increased risk of incident fractures: the MrOS Sweden study. J Bone Miner Res 26:865–872

Peister A, Mellad JA, Larson BL, Hall BM, Gibson LF, Prockop DJ (2004) Adult stem cells from bone marrow (MSCs) isolated from different strains of inbred mice vary in surface epitopes, rates of proliferation, and differentiation potential. Blood 103:1662–1668

Perrini S, Natalicchio A, Laviola L, Cignarelli A, Melchiorre M, De SF, Caccioppoli C, Leonardini A, Martemucci S, Belsanti G, Miccoli S, Ciampolillo A, Corrado A, Cantatore FP, Giorgino R, Giorgino F (2008) Abnormalities of insulin-like growth factor-I signaling and impaired cell proliferation in osteoblasts from subjects with osteoporosis. Endocrinology 149:1302–1313

Perrini S, Laviola L, Carreira MC, Cignarelli A, Natalicchio A, Giorgino F (2010) The GH/IGF1 axis and signaling pathways in the muscle and bone: mechanisms underlying age-related skeletal muscle wasting and osteoporosis. J Endocrinol 205:201–210

Post S, Abdallah BM, Bentzon JF, Kassem M (2008) Demonstration of the presence of independent pre-osteoblastic and pre-adipocytic cell populations in bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Bone 43:32–39

Qiu W, Hu Y, Andersen TE, Jafari A, Li N, Chen W, Kassem M (2010) Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 19 (TNFRSF19) regulates differentiation fate of human mesenchymal (stromal) stem cells through canonical Wnt signaling and C/EBP. J Biol Chem 285:14438–14449

Raucci A, Bellosta P, Grassi R, Basilico C, Mansukhani A (2008) Osteoblast proliferation or differentiation is regulated by relative strengths of opposing signaling pathways. J Cell Physiol 215:442–451

Rosen CJ (2004) Insulin-like growth factor I and bone mineral density: experience from animal models and human observational studies. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 18:423–435

Rosen CJ, Dimai HP, Vereault D, Donahue LR, Beamer WG, Farley J, Linkhart S, Linkhart T, Mohan S, Baylink DJ (1997) Circulating and skeletal insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) concentrations in two inbred strains of mice with different bone mineral densities. Bone 21:217–223

Rosen CJ, Kurland ES, Vereault D, Adler RA, Rackoff PJ, Craig WY, Witte S, Rogers J, Bilezikian JP (1998) Association between serum insulin growth factor-I (IGF-I) and a simple sequence repeat in IGF-I gene: implications for genetic studies of bone mineral density. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83:2286–2290

Saeed H, Abdallah BM, Ditzel N, Catala-Lehnen P, Qiu W, Amling M, Kassem M (2011) Telomerase-deficient mice exhibit bone loss owing to defects in osteoblasts and increased osteoclastogenesis by inflammatory microenvironment. J Bone Miner Res 26:1494–1505

Schmid C, Rutishauser J, Schlapfer I, Froesch ER, Zapf J (1991) Intact but not truncated insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3) blocks IGF I-induced stimulation of osteoblasts: control of IGF signalling to bone cells by IGFBP-3-specific proteolysis? Biochem Biophys Res Commun 179:579–585

Seck T, Scheidt-Nave C, Leidig-Bruckner G, Ziegler R, Pfeilschifter J (2001) Low serum concentrations of insulin-like growth factor I are associated with femoral bone loss in a population-based sample of postmenopausal women. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 55:101–106

Severgnini S, Lowenthal DT, Millard WJ, Simmen FA, Pollock BH, Borst SE (1999) Altered IGF-I and IGFBPs in senescent male and female rats. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 54:B111–B115

Shie JH, Liu HT, Kuo HC (2012) Increased cell apoptosis of urothelium mediated by inflammation in interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. Urology 79:484–513

Simonsen JL, Rosada C, Serakinci N, Justesen J, Stenderup K, Rattan SI, Jensen TG, Kassem M (2002) Telomerase expression extends the proliferative life-span and maintains the osteogenic potential of human bone marrow stromal cells. Nat Biotechnol 20:592–596

Sjogren K, Liu JL, Blad K, Skrtic S, Vidal O, Wallenius V, LeRoith D, Tornell J, Isaksson OG, Jansson JO, Ohlsson C (1999) Liver-derived insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) is the principal source of IGF-I in blood but is not required for postnatal body growth in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:7088–7092

Sugimoto T, Nishiyama K, Kuribayashi F, Chihara K (1997) Serum levels of insulin-like growth factor (IGF) I, IGF-binding protein (IGFBP)-2, and IGFBP-3 in osteoporotic patients with and without spinal fractures. J Bone Miner Res 12:1272–1279

Tsugawa K, Jones MK, Akahoshi T, Moon WS, Maehara Y, Hashizume M, Sarfeh IJ, Tarnawski AS (2003a) Abnormal PTEN expression in portal hypertensive gastric mucosa: a key to impaired PI 3-kinase/Akt activation and delayed injury healing? FASEB J 17:2316–2318

Tsugawa K, Jones MK, Akahoshi T, Moon WS, Maehara Y, Hashizume M, Sarfeh IJ, Tarnawski AS (2003b) Abnormal PTEN expression in portal hypertensive gastric mucosa: a key to impaired PI 3-kinase/Akt activation and delayed injury healing? FASEB J 17:2316–2318

Xia L, Wang XX, Hu XS, Guo XG, Shang YP, Chen HJ, Zeng CL, Zhang FR, Chen JZ (2008) Resveratrol reduces endothelial progenitor cells senescence through augmentation of telomerase activity by Akt-dependent mechanisms. Br J Pharmacol 155:387

Xian L, Wu X, Pang L, Lou M, Rosen CJ, Qiu T, Crane J, Frassica F, Zhang L, Rodriguez JP, Xiaofeng J, Shoshana Y, Shouhong X, Argiris E, Mei W, Xu C (2012) Matrix IGF-1 maintains bone mass by activation of mTOR in mesenchymal stem cells. Nat Med 18:1095–1101

Xue P, Wu X, Zhou L, Ma H, Wang Y, Liu Y, Ma J, Li Y (2013) IGF1 promotes osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells derived from rat bone marrow by increasing TAZ expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 433:226–231

Yakar S, Rosen CJ, Beamer WG, Ackert-Bicknell CL, Wu Y, Liu JL, Ooi GT, Setser J, Frystyk J, Boisclair YR, LeRoith D (2002) Circulating levels of IGF-1 directly regulate bone growth and density. J Clin Investig 110:771–781

Yamaguchi T, Kanatani M, Yamauchi M, Kaji H, Sugishita T, Baylink DJ, Mohan S, Chihara K, Sugimoto T (2006) Serum levels of insulin-like growth factor (IGF); IGF-binding proteins-3, -4, and -5; and their relationships to bone mineral density and the risk of vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women. Calcif Tissue Int 78:18–24

Ye J, Renault VM, Jamet K, Gilson E (2014) Transcriptional outcome of telomere signalling. Nat Rev Genet 15:491–503

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by Grants from the Lundbeck foundation, the NovoNordisk Foundation. H. Saeed has received Ph.D. fellowship from the NovoNordisk Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors have no conflict of interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

10522_2015_9596_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Supplementary material 1 (PDF 221 kb). Fig. S1. Differential gene expression in hMSC-TERT compared to primary hMSC. Microarray analysis was performed for hMSC-TERT and primary isolated hMSC at baseline. a Pie chart showing number of genes that are differentially regulated in hMSC-TERT compared to hMSCs. b Components of IGF signaling pathway that exhibited significant changes in hMSC-TERT. Up-regulated genes are represented in red color, while down-regulated genes are represented in green color

10522_2015_9596_MOESM2_ESM.pdf

Supplementary material 2 (PDF 12 kb). Genes are clustered according to biological function and involvement in relevant signaling Pathways

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Saeed, H., Qiu, W., Li, C. et al. Telomerase activity promotes osteoblast differentiation by modulating IGF-signaling pathway. Biogerontology 16, 733–745 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10522-015-9596-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10522-015-9596-6