Abstract

Greater height and higher intelligence test scores are predictors of better health outcomes. Here, we used molecular (single-nucleotide polymorphism) data to estimate the genetic correlation between height and general intelligence (g) in 6,815 unrelated subjects (median age 57, IQR 49–63) from the Generation Scotland: Scottish Family Health Study cohort. The phenotypic correlation between height and g was 0.16 (SE 0.01). The genetic correlation between height and g was 0.28 (SE 0.09) with a bivariate heritability estimate of 0.71. Understanding the molecular basis of the correlation between height and intelligence may help explain any shared role in determining health outcomes. This study identified a modest genetic correlation between height and intelligence with the majority of the phenotypic correlation being explained by shared genetic influences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Evidence from observational studies suggests that better cognitive performance (as assessed by IQ-type tests) is associated with better health outcomes and lower mortality risk (Calvin et al. 2011; Deary et al. 2010; Whalley and Deary 2001). Greater height is also associated with a lower risk of a series of health outcomes including coronary heart disease, stroke, accidents and suicide (Batty et al. 2009; Lee et al. 2009; Paajanen et al. 2010; Whitley et al. 2010).

Height and intelligence are positively correlated (Gale 2005), with r typically between 0.10 and 0.20 (Keller et al. 2013). Both traits are partly heritable: behaviour genetic studies, mostly using twin samples, provide narrow sense heritability estimates of 70–90 % for height (Macgregor et al. 2006; Silventoinen et al. 2003) and 40–70 % for intelligence (Calvin et al. 2012; Haworth et al. 2010). More recently, molecular-based studies indicate that about 45 % of the variation in height (Yang et al. 2010) and 25–50 % of the variance in intelligence (Benyamin et al. 2013; Davies et al. 2011) can be explained by additive effects of common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). However, to date, genetic correlations between height and intelligence have been calculated using only twin or family based data, in which relatedness is defined via pedigree information. They indicate varying estimates of the height-intelligence genetic correlation that range between 0.08 and 0.30 (Beauchamp et al. 2011; Keller et al. 2013; Silventoinen et al. 2006; Sundet et al. 2005). Whereas the benefits of the twin approach include testing for pleiotropic and assortative mating contributions to the correlation (Keller et al. 2013), and the opportunity to incorporate rare variants and non-additive genetic variation, drawbacks include the equal environments assumption (that is, there is no differential environment for monozygotic and dizygotic twins) and an inability to target specific causal variants and molecular pathways.

Here, we used a molecular genetic approach to examine the genetic correlation between height and intelligence in a large sample of unrelated adults. The method applied investigates phenotypic similarities in genetically similar (based on molecular level SNP data) unrelated individuals.

Methods

Generation Scotland: the Scottish Family Health Study (GS:SFHS) is a family structured, population-based cohort study (Smith et al. 2006, 2012). A full description of the study is provided elsewhere (Smith et al. 2006, 2012; www.generationscotland.org/). In brief, over 24,000 participants were recruited between 2006 and 2011. Probands (n = 7,953) were aged between 35 and 65 years and were registered with participating general medical practitioners (GPs) in the Glasgow, Tayside, Ayrshire, Arran, and North-East regions of Scotland. These individuals were not ascertained on the basis of having any particular disorder. Their family members were also recruited to yield the full study sample.

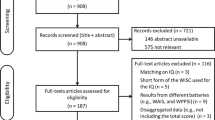

Genotyping Sample

Genome-wide data were collected on a sub-sample of 10,000 participants using the Illumina HumanOmniExpressExome-8 v1.0 DNA Analysis BeadChip and Infinium chemistry (Gunderson 2009). Blood samples (or saliva from postal and a few clinical participants) from GS:SFHS participants were collected, processed and stored using standard operating procedures and managed through a laboratory information management system at the Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility Genetics Core, Edinburgh (Kerr et al. 2013). The yield of DNA was measured using picogreen and normalised to 50 ng/μl before genotyping. The arrays were imaged on an Illumina HiScan platform and genotypes were called automatically using GenomeStudio Analysis software v2011.1. After quality control, there were a total of 594,824 SNPs available for analysis on 9,863 individuals, which included family trios and quads in addition to unrelated participants. A genetic threshold of 0.025 (between second and third cousins) was used to remove potential shared environment effects (Yang et al. 2010, 2011). This left an unrelated sample size of 6,815. SNPs with a MAF below 1 % were excluded prior to the analysis.

Ethics Statement

All components of GS:SFHS received ethical approval from the NHS Tayside Committee on Medical Research Ethics (REC Reference Number: 05/S1401/89). GS:SFHS has also been granted Research Tissue Bank status by the Tayside Committee on Medical Research Ethics (REC Reference Number: 10/S1402/20), providing generic ethical approval for a wide range of uses within medical research.

Cognition and Height

General intelligence was assessed by extracting the first, unrotated principal component from four cognitive tests that measured processing speed (Wechsler digit symbol substitution task—DST; Wechsler 1998a), verbal declarative memory (Wechsler logical memory test—LM; sum of immediate and delayed recall of one paragraph; Wechsler 1998b), executive function (verbal fluency test—VFT; using the letters C, F, and L, each for 1 min; Lezak 1995), and vocabulary (the Mill Hill vocabulary scale—MHVS; junior and senior synonyms combined; Raven et al. 1977). This component, which we label g, explained 45 % of the variance of the four tests, each of which loaded strongly on the component (0.64–0.72). These loadings represent the weight that each individual’s (standardised) cognitive test scores needs to be multiplied by in order to obtain their g score.

Height was measured during clinical examination by asking each participant to remove their shoes and to stand (i) as erectly as possible with their back and shoulders against the freestanding measurement device, (ii) with heels together and feet angled at about 60°, and (iii) with head held in the Frankfort horizontal plane, where the inferior border of the bony orbit is in line with the groove at the top of the tragus of the ear. Height to the nearest half centimetre was then measured during quiet breathing, with the horizontal arm of the measuring unit being kept at a rigid right angle to the scale.

Statistical Analyses

Age-, sex-, and population stratification-adjusted residuals for both g and height were computed by linear regression. The number of ancestry components was determined by comparing the log-likelihoods and residual errors from linear regression models of the traits on age, sex, and up to 20 principal components (Supplementary Fig. 1). Based on these results, we adjusted for 14 components, which accounted for 1.0 % of the variance in g, and 0.8 % of the variance in height.

The residual values were carried forward to the genome-wide complex trait analyses—GCTA (Yang et al. 2010, 2011). Initially, univariate models were run for each trait to investigate the proportion of phenotypic variance that is explained by common genetic variants and variants that are in high linkage disequilibrium with them. The univariate GCTA estimates for g have been reported previously (Marioni et al., in press). Bivariate GCTA models (Lee et al. 2012) were then run to obtain estimates of the genetic correlation and bivariate heritability between height and g.

Results

Descriptive details of the genotyped Generation Scotland cohort and the analysis cohort of unrelated study members are presented in Table 1. The median age of the genotyped cohort was 54 years (IQR 43–62), and 59 % of participants were female. As anticipated, men (mean height 176 cm [SD 7]) were taller than women (mean height 162 cm [SD 7]). The age- and sex-adjusted phenotypic correlation between height and g was 0.16 (SE 0.01). The unrelated subjects are representative of the full genotyped cohort, with negligible differences in the summary information.

The univariate and bivariate GCTA results are presented in Table 2, with full output in Supplementary Tables I and II. The proportion of variance in the traits that was explained by the common SNPs was 0.58 (SE 0.05) for height, and 0.28 (SE 0.05) for g.

The genetic correlation for height and g was 0.28 (SE 0.09). Bivariate heritability estimates indicated that the majority (71 %) of the phenotypic correlation between height and g was explained by common additive genetic variants.

Discussion

In this study we found a moderate and statistically significant genetic correlation between height and general intelligence, g. Whereas the phenotypic correlation between these measures was small (~0.16), the bulk of this correlation can be explained by common additive genetic variants, and variants in linkage disequilibrium with them.

The main limitation of our analysis compared to previously reported findings from twin and family based data (Beauchamp et al. 2011; Keller et al. 2013; Silventoinen et al. 2006; Sundet et al. 2005) is its inability to determine the degree to which the correlation depends on assortative mating versus pleiotropy (Keller et al. 2013). In their study, Keller et al. (2013) used a bivariate nuclear twin family study design; however, there is no obvious analogue to such an approach for molecular level data. A further limitation of the model is that it only considered common variants (MAF > 1 %) and additive effects. This does not bias the estimate of the genetic correlation (Trzaskowski et al. 2013) but does result in lower univariate estimates for the traits compared to the corresponding figures from twin studies, which include non-additive genetic effects and the influence of rare variants.

The primary advantage of our analysis is that we can quantify the common additive SNP contribution to the phenotypic correlation and the overlap of these SNP effects on the variance explained in each of the two traits. Such an approach determines the molecular signal size and is the start to understanding the underlying biology of the genetic correlation. Other strengths include the large sample size, which is essential for calculating precise genetic correlation estimates; the phenotypic measure of g, which was derived from a battery of four cognitive tests; and the ethnic homogeneity of the Generation Scotland sample.

The findings from our molecular genetic study are in accordance with those reported in previous twin and family based analyses, where estimates of the height-cognition genetic correlation vary between 0.20 and 0.35 (Beauchamp et al. 2011; Silventoinen et al. 2006; Sundet et al. 2005). However, the most recent study in this area presented more modest genetic correlations of 0.08 for men, and 0.17 for women in a population of around 8,000 subjects from nearly 3,000 families (Keller et al. 2013). Reasons for cross-cohort differences have been reported by Keller et al. (2013) and may include birth cohort effects that are related to nutritional differences, childhood infections, and social circumstances.

Understanding the genetic correlation between height and IQ is important in life-course research as both traits have been described as predictors of health outcomes and mortality. Short stature has been linked to cardiovascular disease risk (Paajanen et al. 2010), and numerous other health outcomes (Batty et al. 2009; Lee et al. 2009; Whitley et al. 2010). Higher IQ has been linked to lower mortality risk, in addition to a decreased risk of a host of health outcomes such as coronary heart disease, stroke, accidents, and suicide (Calvin et al. 2011; Deary et al. 2010; Whalley and Deary 2001). There is also a complex interplay between height and intelligence and their role in both development and late-life ageing. Cognitive change from age 11 to 79 years has been shown to predict height loss between ages 79 and 87 years (Starr et al. 2010). The reason for the intelligence-health relation is not fully understood. One of several non-exclusive possibilities is that height and intelligence are both markers of ‘system integrity’ (Deary 2012). The present phenotypic and genetic correlation between them provides partial support for that suggestion. Further research should examine whether their shared genetic variation is associated with health outcomes, and seek to identify the molecular mechanisms.

In conclusion, we found a moderate molecular genetic correlation between height and intelligence. Furthermore, the majority of the phenotypic correlation between the traits can be explained by shared genetic influences.

References

Batty GD, Shipley MJ, Gunnell D, Huxley R, Kivimaki M, Woodward M, Lee CM, Smith GD (2009) Height, wealth, and health: an overview with new data from three longitudinal studies. Econ Hum Biol 7(2):137–152

Beauchamp JP, Cesarini D, Johannesson M, Lindqvist E, Apicella C (2011) On the sources of the height-intelligence correlation: new insights from a bivariate ACE model with assortative mating. Behav Genet 41(2):242–252

Benyamin B, Pourcain B, Davis OS, Davies G, Hansell NK, Brion MJ, Kirkpatrick RM, Cents RA, Franić S, Miller MB, Haworth CM, Meaburn E, Price TS, Evans DM, Timpson N, Kemp J, Ring S, McArdle W, Medland SE, Yang J, Harris SE, Liewald DC, Scheet P, Xiao X, Hudziak JJ, de Geus EJ, Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2 (WTCCC2), Jaddoe VW, Starr JM, Verhulst FC, Pennell C, Tiemeier H, Iacono WG, Palmer LJ, Montgomery GW, Martin NG, Boomsma DI, Posthuma D, McGue M, Wright MJ, Davey Smith G, Deary IJ, Plomin R, Visscher PM (2013) Childhood intelligence is heritable, highly polygenic and associated with FNBP1L. Mol Psychiatry 19(2):253–258

Calvin CM, Deary IJ, Fenton C, Roberts BA, Der G, Leckenby N, Batty GD (2011) Intelligence in youth and all-cause-mortality: systematic review with meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol 40(3):626–644

Calvin CM, Deary IJ, Webbink D, Smith P, Fernandes C, Lee SH, Luciano M, Visscher PM (2012) Multivariate genetic analyses of cognition and academic achievement from two population samples of 174,000 and 166,000 school children. Behav Genet 42(5):699–710

Davies G, Tenesa A, Payton A, Yang J, Harris SE, Liewald D, Ke X, Le Hellard S, Christoforou A, Luciano M, McGhee K, Lopez L, Gow AJ, Corley J, Redmond P, Fox HC, Haggarty P, Whalley LJ, McNeill G, Goddard ME, Espeseth T, Lundervold AJ, Reinvang I, Pickles A, Steen VM, Ollier W, Porteous DJ, Horan M, Starr JM, Pendleton N, Visscher PM, Deary IJ (2011) Genome-wide association studies establish that human intelligence is highly heritable and polygenic. Mol Psychiatry 16(10):996–1005

Deary IJ (2012) Looking for ‘system integrity’ in cognitive epidemiology. Gerontology 58:545–553

Deary IJ, Weiss AW, Batty GD (2010) Intelligence and personality as predictors of illness and death: how researchers in differential psychology and chronic disease epidemiology are collaborating to understand and address health inequalities. Psychol Sci Public Interests 11(2):53–79

Gale C (2005) Commentary: height and intelligence. Int J Epidemiol 34(3):678–679

Gunderson KL (2009) Whole-genome genotyping on bead arrays. Methods Mol Biol 529:197–213

Haworth CM, Wright MJ, Luciano M, Martin NG, de Geus EJ, van Beijsterveldt CE, Bartels M, Posthuma D, Boomsma DI, Davis OS, Kovas Y, Corley RP, Defries JC, Hewitt JK, Olson RK, Rhea SA, Wadsworth SJ, Iacono WG, McGue M, Thompson LA, Hart SA, Petrill SA, Lubinski D, Plomin R (2010) The heritability of general cognitive ability increases linearly from childhood to young adulthood. Mol Psychiatry 15(11):1112–1120

Keller MC, Garver-Apgar CE, Wright MJ, Martin NG, Corley RP, Stallings MC, Hewitt JK, Zietsch BP (2013) The genetic correlation between height and IQ: shared genes or assortative mating? PLoS Genet 9(4):e1003451

Kerr SM, Campbell A, Murphy L, Hayward C, Jackson C, Wain LV, Tobin MD, Dominiczak A, Morris A, Smith BH, Porteous DJ (2013) Pedigree and genotyping quality analyses of over 10,000 DNA samples from the Generation Scotland: Scottish Family Health Study. BMC Med Genet 14(1):38

Lee CM, Barzi F, Woodward M, Batty GD, Giles GG, Wong JW, Jamrozik K, Lam TH, Ueshima H, Kim HC, Gu DF, Schooling M, Huxley RR, Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration (2009) Adult height and the risks of cardiovascular disease and major causes of death in the Asia-Pacific region: 21,000 deaths in 510,000 men and women. Int J Epidemiol 38(4):1060–1071

Lee SH, Yang J, Goddard ME, Visscher PM, Wray NR (2012) Estimation of pleiotropy between complex diseases using single-nucleotide polymorphism-derived genomic relationships and restricted maximum likelihood. Bioinformatics 28(19):2540–2542

Lezak MD (1995) Neuropsychological assessment, 3rd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Macgregor S, Cornes BK, Martin NG, Visscher PM (2006) Bias, precision and heritability of self-reported and clinically measured height in Australian twins. Hum Genet 120(4):571–580

Marioni RE, Davies G, Hayward C, Liewald D, Kerr SM, Campbell A, Luciano M, Smith BH, Padmanabhan S, Hocking LJ, Hastie ND, Wright AF, Porteous DJ, Visscher PM, Deary IJ (in press). Molecular genetic contributions to socioeconomic status and intelligence. Intelligence

Paajanen TA, Oksala NK, Kuukasjärvi P, Karhunen PJ (2010) Short stature is associated with coronary heart disease: a systematic review of the literature and a meta-analysis. Eur Heart J 31(14):1802–1809

Raven JC, Court JH, Raven J (1977) Manual for Raven’s progressive matrices and vocabulary scales. HK Lewis, London

Silventoinen K, Sammalisto S, Perola M, Boomsma DI, Cornes BK, Davis C, Dunkel L, De Lange M, Harris JR, Hjelmborg JV, Luciano M, Martin NG, Mortensen J, Nisticò L, Pedersen NL, Skytthe A, Spector TD, Stazi MA, Willemsen G, Kaprio J (2003) Heritability of adult body height: a comparative study of twin cohorts in eight countries. Twin Res 6(5):399–408

Silventoinen K, Posthuma D, van Beijsterveldt T, Bartels M, Boomsma DI (2006) Genetic contributions to the association between height and intelligence: evidence from Dutch twin data from childhood to middle age. Genes Brain Behav 5(8):585–595

Smith BH, Campbell H, Blackwood D, Connell J, Connor M, Deary IJ, Dominiczak AF, Fitzpatrick B, Ford I, Jackson C, Haddow G, Kerr S, Lindsay R, McGilchrist M, Morton R, Murray G, Palmer CN, Pell JP, Ralston SH, St Clair D, Sullivan F, Watt G, Wolf R, Wright A, Porteous D, Morris AD (2006) Generation Scotland: the Scottish Family Health Study; a new resource for researching genes and heritability. BMC Med Genet 7:74

Smith BH, Campbell A, Linksted P, Fitzpatrick B, Jackson C, Kerr SM, Deary IJ, Macintyre DJ, Campbell H, McGilchrist M, Hocking LJ, Wisely L, Ford I, Lindsay RS, Morton R, Palmer CN, Dominiczak AF, Porteous DJ, Morris AD (2012) Cohort profile: Generation Scotland: Scottish Family Health Study (GS:SFHS). The study, its participants and their potential for genetic research on health and illness. Int J Epidemiol 42(3):689–700

Starr JM, Kilgour A, Pattie A, Gow A, Bates TC, Deary IJ (2010) Height and intelligence in the Lothian Birth Cohort 1921: a longitudinal study. Age Ageing 39(2):272–275

Sundet JM, Tambs K, Harris JR, Magnus P, Torjussen TM (2005) Resolving the genetic and environmental sources of the correlation between height and intelligence: a study of nearly 2600 Norwegian male twin pairs. Twin Res Hum Genet 8(4):307–311

Trzaskowski M, Davis OS, DeFries JC, Yang J, Visscher PM, Plomin R (2013) DNA evidence for strong genome-wide pleiotropy of cognitive and learning abilities. Behav Genet 43(4):267–273

Wechsler D (1998a) WAIS-III UK Wechsler adult intelligence scale. Psychological Corporation, London

Wechsler D (1998b) WMS-III UK, Wechsler memory scale-revised. Psychological Corporation, London

Whalley LJ, Deary IJ (2001) Longitudinal cohort study of childhood IQ and survival up to age 76. BMJ 322(7290):819

Whitley E, Rasmussen F, Tynelius P, Batty GD (2010) Physical stature and method-specific attempted suicide: cohort study of one million men. Psychiatry Res 179(1):116–118

Yang J, Benyamin B, McEvoy BP, Gordon S, Henders AK, Nyholt DR, Madden PA, Heath AC, Martin NG, Montgomery GW, Goddard ME, Visscher PM (2010) Common SNPs explain a large proportion of the heritability for human height. Nat Genet 42:565–569

Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME, Visscher PM (2011) GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am J Hum Genet 88(1):76–82

Acknowledgments

Generation Scotland has received core funding from the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health Directorates CZD/16/6 and the Scottish Funding Council HR03006. We are grateful to all the families who took part, the general practitioners and the Scottish School of Primary Care for their help in recruiting them, and the whole Generation Scotland team, which includes interviewers, computer and laboratory technicians, clerical workers, research scientists, volunteers, managers, receptionists, healthcare assistants and nurses. Genotyping of the GS:SFHS samples was carried out by the Genetics Core Laboratory at the Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility, Edinburgh, Scotland and was funded by the UK Medical Research Council (MRC). The Quantitative Trait Locus team at the Human Genetics Unit are funded by the MRC. IJD and GDB are members of the Alzheimer Scotland Dementia Research Centre funded by Alzheimer Scotland. REM, GDB, DJP, PMV, and IJD undertook the work within The University of Edinburgh Centre for Cognitive Ageing and Cognitive Epidemiology (MR/K026992/1), part of the cross council Lifelong Health and Wellbeing Initiative. Funding from the BBSRC, and MRC is gratefully acknowledged.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5). Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Edited by Stacey Cherny.

Generation Scotland—A collaboration between the University Medical Schools and National Health Service in Aberdeen, Dundee, Edinburgh and Glasgow.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Marioni, R.E., Batty, G.D., Hayward, C. et al. Common Genetic Variants Explain the Majority of the Correlation Between Height and Intelligence: The Generation Scotland Study. Behav Genet 44, 91–96 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-014-9644-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-014-9644-z