Abstract

This study assessed Kinsey self-ratings and lifetime sexual experiences of 17-year-olds whose lesbian mothers enrolled before these offspring were born in the longest-running, prospective study of same-sex parented families, with a 93% retention rate to date. Data for the current report were gathered through online questionnaires completed by 78 adolescent offspring (39 girls and 39 boys). The adolescents were asked if they had ever been abused and, if so, to specify by whom and the type of abuse (verbal, emotional, physical, or sexual). They were also asked to specify their sexual identity on the Kinsey scale, between exclusively heterosexual and exclusively homosexual. Lifetime sexual behavior was assessed through questions about heterosexual and same-sex contact, age of first sexual experience, contraception use, and pregnancy. The results revealed that there were no reports of physical or sexual victimization by a parent or other caregiver. Regarding sexual orientation, 18.9% of the adolescent girls and 2.7% of the adolescent boys self-rated in the bisexual spectrum, and 0% of girls and 5.4% of boys self-rated as predominantly-to-exclusively homosexual. When compared with age- and gender-matched adolescents of the National Survey of Family Growth, the study offspring were significantly older at the time of their first heterosexual contact, and the daughters of lesbian mothers were significantly more likely to have had same-sex contact. These findings suggest that adolescents reared in lesbian families are less likely than their peers to be victimized by a parent or other caregiver, and that daughters of lesbian mothers are more likely to engage in same-sex behavior and to identify as bisexual.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Research has established that there are no significant differences in psychological well-being between the children of lesbian and heterosexual parents (Bos, van Balen, & Van den Boom, 2007; Gartrell, Deck, Rodas, Peyser, & Banks, 2005; Golombok, 2007; Perrin & American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, 2002; Tasker, 2005; Vanfraussen, Ponjaert-Kristoffersen, & Brewaeys, 2002, 2003), but there are very limited data on the sexual orientation, sexual behavior, and sexual risk exposure of adolescents reared since birth in what are known as planned lesbian families (Bos & Sandfort, 2010; Gartrell & Bos, 2010; Golombok & Badger, 2010; Perrin, 2002).

The prevailing view of sexual orientation is that it is shaped by a variety of determinants, including genetic influences, hormonal factors, and family environments (Golombok, 2000). Empirical data suggest that genetics may play a role: Sibling studies show more concordance in sexual orientation between genetically identical monozygotic twins than between dizygotic twins or other siblings (Bailey, Dunne, & Martin, 2000; Kendler, Thornton, Gilman, & Kessler, 2000; Langstrom, Rahman, Carlstrom, & Lichtenstein, 2010). Extrapolating from these findings, researchers have theorized that lesbian and gay parents may have a higher proportion of biologic lesbian or gay offspring as a result of shared genetic material (Goldberg, 2010). In terms of hormonal factors, high maternal levels of androgens during pregnancy have been associated with more same-sex attraction in offspring (Hines, Brook, & Conway, 2004). Among possible environmental influences, growing up in a same-sex parent household may broaden offspring’s consideration of possible sexual identities because lesbian and gay parents are less likely to stigmatize same-sex attraction and relationships, and they are more likely to discuss issues related to sexuality with their offspring (Bos & Sandfort, 2010; Fulcher, Sutfin, & Patterson, 2008; Goldberg, 2010; Tasker, 2005). As Stacey and Biblarz (2001; see also Biblarz & Stacey, 2010) theorize, the adolescent offspring of same-sex parents may be more comfortable exploring homoerotic attractions than youth who grow up in heterosexual households because of the social environment created by their parents.

Another claim about the origins of sexual orientation that has been put forth in litigation and public discourse by opponents of equality in marriage, adoption, and foster care for same-sex couples is that lesbian and gay parents are more likely to abuse their children sexually (Arkansas Department of Human Services, 2010; Ford, 2010), and that this abuse will, in turn, result in their offspring identifying as lesbian or gay themselves (Biblarz & Stacey, 2010; Committee on Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Concerns, Committee on Children, Youth, and Families, Committee on Women in Psychology, 2005; Falk, 1989; Golombok & Tasker, 1994; Jenny, 1994; Patterson, 1992; Thompson, 2002). Although no studies to date have investigated intrafamilial sexual abuse of adolescents reared in planned same-sex parent households, a growing body of research has found that lesbian and gay adults, most of whom grew up in heterosexual households, report higher rates of childhood sexual victimization than their heterosexual peers (Balsam, Lehavot, Beadnell, & Circo, 2010; Balsam, Rothblum, & Beauchaine, 2005; Wilson & Widom, 2010). The authors of these studies reporting a correlation between childhood sexual abuse and adult same-sex attraction and/or behavior urge caution in the interpretations of their findings, suggesting that a child’s same-sex attraction could have preceded the abuse or that young children who demonstrate same-sex attraction may be specifically targeted for abuse (Balsam et al., 2005; Faulkner & Cranston, 1998; Wilson & Widom, 2010).

Although the sexual orientation and behavior of adolescents and adults reared by same-sex couples has garnered considerable attention in research and public policy (Arkansas Department of Human Services, 2010; Supreme Court of Iowa, 2009; United States District Court Northern District of California San Francisco Division, 2010), the only data on the sexual preferences and experiences of the offspring of lesbian mothers come from two empirical studies of young adults (Golombok & Badger, 2010; Golombok & Tasker, 1996; Golombok, Tasker, & Murray, 1997; MacCallum & Golombok, 2004; Tasker & Golombok, 1995).

The first report on the sexual orientation of adults who had been reared by lesbian mothers was based on data collected in 1991–1992 in the United Kingdom by Golombok and Tasker (1996; see also Tasker & Golombok, 1995). Twenty-five adult offspring (17 women and eight men) of lesbian mothers and 21 adult offspring (nine women and 12 men) of heterosexual mothers were interviewed. This study was a follow-up to a survey of their mothers conducted in 1976–1977. In the lesbian families, the offspring had been conceived in heterosexual relationships before their mothers divorced and identified as lesbian. The average age of the adult offspring in the follow-up study was 23.5 years. Golombok and Tasker found no significant differences between the groups of lesbian- and heterosexual-parented offspring in the percentage who self-identified as lesbian or gay or in reports of sexual attraction. Golombok and Tasker did, however, find that six of the young adults (five females and one male) raised by lesbian parents reported a sexual experience with someone of the same gender, while none of the young adults raised by heterosexual mothers did. Additionally, only the adult daughters (and no adult sons) of lesbians expressed a significantly greater openness to the idea of same-sex attraction in the future.

In a second British study, planned lesbian families were compared with solo heterosexual mother families and two-parent heterosexual families (Golombok & Badger, 2010; Golombok et al., 1997; MacCallum & Golombok, 2004). All of the lesbian mothers identified as lesbian before the birth of the child enrolled in this study. The first interviews took place when these offspring were, on average, 6 years of age. The offspring were surveyed again as young adults (M = 19 years; range, 18–19.5) (Golombok & Badger, 2010). It was found that the 18 young adults with lesbian mothers were more likely to have started dating than the 32 young adults from two-parent heterosexual families; all those reared by lesbian mothers identified as heterosexual with the exception of one young woman who reported that she was bisexual.

Two other studies have explored sexual orientation, sexual behavior, and ideas about sexuality in female-headed households (Bos & Sandfort, 2010; Wainright, Russell, & Patterson, 2004). Wainright et al. analyzed data on 44 15-year-olds reared in female-couple households (parental sexual orientation unknown and planned family status unknown) collected in the 1994 National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Wainright et al. compared the adolescents from these same-sex-parent households to 44 age-matched adolescents raised in heterosexual-parent households and found no significant differences in self-reports of heterosexual intercourse, sexual attraction, or romantic relationships. In a recent study of planned lesbian families in the Netherlands, Bos and Sandfort (2010) compared the offspring, ranging in age from 8 to 12 years, from 63 planned lesbian families to the offspring from 68 heterosexual families. The children of lesbian mothers were less certain about the prospect of future heterosexual involvement. This finding does not necessarily equate with future sexual orientation or behavior, but it fits with the theory proposed by Biblarz and Stacey (2010) and Stacey and Biblarz (2001) and the evidence presented in Golombok et al. (1997) that children growing up in lesbian-parent households may be more open to the possibility of same-sex relationships in the future.

The U.S. National Longitudinal Lesbian Family Study (NLLFS) provides an opportunity to fill gaps in the literature about the offspring of planned lesbian families. The NLLFS was initiated in 1986 to provide prospective data on a cohort of lesbian families from the time the children were conceived until they reach adulthood. The first NLLFS interview (T1) (Gartrell et al., 1996), conducted with inseminating or pregnant prospective mothers, found that the children were highly desired. The study participants, who were completely open about being lesbian, hoped that their families of origin would welcome the child even though some family members had concerns about children being raised by lesbians. The second interview (T2) (Gartrell et al., 1999) took place when the NLLFS children were 2-years-old. Child-rearing responsibilities were typically shared in two-mother households. Most children had accepting grandparents who had become closer to the family since the child’s birth. At T3 (Gartrell et al., 2000), the 5-year-old index children were reported to be healthy, well-adjusted, and relating well to peers. The NLLFS families were integrated into their neighborhoods and participating in the lesbian community. When the NLLFS offspring were 10 (T4) (Gartrell et al., 2005) and 17 (T5) (Gartrell & Bos, 2010), standardized tests completed by their mothers revealed that their offspring had no higher incidence of psychological or developmental problems than age-matched peers in the comparison samples. Also at T4, the NLLFS mothers reported that none of their offspring had been physically or sexually abused by a parent or other caregiver (Gartrell, Rodas, Deck, Peyser, & Banks, 2006; Gartrell et al., 2005).

The first goal of the current investigation was to survey the 17-year-old NLLFS offspring about their sexual orientation, sexual behavior, and sexual risk exposure. The second goal was to compare the sexual behavior of the NLLFS adolescents with the sexual behavior reported by age-matched adolescents in national probability samples.

Method

Participants

The data for this report were collected between 2005 and 2009 as part of the NLLFS, an ongoing longitudinal study of 84 planned lesbian families that began in 1986 and has a 93% retention rate to date. The sample consisted of 39 adolescent girls and 39 adolescent boys who were conceived through donor insemination. Their mothers enrolled in the NLLFS between 1986 and 1992 while inseminating or pregnant with these index offspring (for a full description of sampling and data collection procedures, see Gartrell & Bos, 2010; Gartrell et al., 1996, 1999, 2000, 2005). At T5, after consent had been obtained from the mothers for the participation of their offspring, the 17-year-old NLLFS adolescents were contacted, who also provided assent. The adolescents were assured that their responses would be kept confidential. Approval for the NLLFS has been granted by the Institutional Review Board at the California Pacific Medical Center.

Since one family did not complete all portions of the T5 survey instruments, the total N used for the analyses was 77 families with 78 adolescents, including one set of twins. Demographic characteristics of the T5 adolescent sample are shown in Table 1. At T5, the family constellations consisted of 31 continuously-coupled, 40 separated-mother, and six single-mother families. Of the 73 couples who were co-parenting when the index offspring were born, 56% had separated, and the average age of the index offspring at the time of their mothers’ separation was 6.97 years (SD = 4.42 years). There was a significant difference between the parental divorce rate (36.3%) of the 17-year-old adolescents in the 6th Cycle of the U.S. National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) and the maternal relationship dissolution rate in the NLLFS (χ2 = 12.32; p = .001) (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2005, 2006). For the NLLFS mothers, custody was shared after separation in 71.4% of cases; in 28.6%, the birthmother was the primary custodial parent. Between T1 and T5, 63 (80.8%) NLLFS adolescents were reared in households in which no adult males resided (for additional demographic information about the NLLFS families, see Gartrell & Bos, 2010; Gartrell et al., 1996, 1999, 2000, 2005).

Measures

The NLLFS adolescents completed an online questionnaire that was provided and returned through the study’s secure Web site. Abuse was measured by the following questions: “Have you ever been abused?” (1 = no, 2 = yes); “If yes, please indicate by whom (e.g., parent, stepparent, relative, friend, stranger, etc.), and for each incident, specify the sex of abuser and the type of abuse (verbal, emotional, physical, sexual).” The NLLFS adolescents were also asked: “How do you identify sexually? (Please check one)”: (0 = exclusively heterosexual; 1 = predominantly heterosexual, incidentally homosexual; 2 = predominantly heterosexual, but more than incidentally homosexual; 3 = equally heterosexual and homosexual; 4 = predominantly homosexual, but more than incidentally heterosexual; 5 = predominantly homosexual, incidentally heterosexual; 6 = exclusively homosexual) (Sell, 1997). Lifetime sexual behavior was assessed through items focusing on heterosexual and same-sex contact, age of first sexual experience, contraception use, and pregnancy (for specific questions, see Table 2).

Data Analysis

For the victimization self-reports and the Kinsey self-ratings, simple frequencies were calculated. In comparing the sexual behavior of NLLFS adolescent girls and boys, chi-square analyses were conducted for discrete variables and t-tests for continuous measures.

To compare sexual behavior in the NLLFS adolescent sample with a national probability sample, the 6th Cycle of the NSFG was used (see Table 2) (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2005, 2006). The NSFG data were weighted to ensure that the sample was similar to the United States population in terms of gender, age, and race/ethnicity. The NSFG questions on sexual behavior were administered through Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interviewing, which ensured privacy by allowing the participant to enter the responses directly into a computer. With permission of the National Center for Health Statistics (A. Chandra & G. Martinez, personal communication, December 4, 2009), the 17-year-old adolescents in the NSFG were selected, consisting of 235 girls and 199 boys. For these 17-year-old NSFG adolescents, weighted frequencies and means were computed for the variables in Table 2. Cross-tabulations and chi-square analyses were used to compare the 17-year-old NLLFS participants with the age-matched NSFG group (weighted data) on: (1) heterosexual contact, same-sex contact, and the prevalence of sexually transmitted infections (separately for adolescent girls and boys); (2) contraception and pregnancy (only for adolescent girls); and (3) impregnation (only for adolescent boys). T-tests were used to compare the NLLFS and the NSFG adolescents (weighted data) on the age of first heterosexual contact, separately by gender.

Results

Victimization

With respect to victimization, one NLLFS adolescent girl (2.6% of the girls) indicated that she had been verbally abused by a stepmother. None of the NLLFS offspring reported physical or sexual abuse by a parent or other caregiver.

Kinsey Self-Ratings

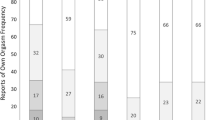

In the NLLFS sample, no significant gender differences were found when the 37 adolescent girls and 37 adolescent boys who self-identified sexually on the Kinsey scale were compared (see Table 3). However, a significant difference was found when gender comparisons were conducted by collapsing the Kinsey scale into three categories: (1) Kinsey 0–1, exclusively heterosexual/predominantly heterosexual, incidentally homosexual; (2) Kinsey 2–4, predominantly heterosexual, but more than incidentally homosexual/equally heterosexual and homosexual/predominantly homosexual, but more than incidentally heterosexual; and (3) Kinsey 5–6, predominantly homosexual, incidentally heterosexual/exclusively homosexual. Eighty-one percent of the girls and 91.9% of the boys identified as Kinsey 0–1; 0% of the girls and 5.4% of the boys identified as Kinsey 5–6. The NLLFS adolescent girls were significantly more likely than the adolescent boys to have identified in the Kinsey 2–4 bisexual spectrum: girls, 18.9%, versus boys, 2.7% (χ2 = 6.75, p = .034).

Sexual Behavior

Lifetime experiences of heterosexual and same-sex contact are shown separately for the NLLFS adolescent girls and boys in Table 3. When the NLLFS adolescent sample was compared by gender with the NSFG 17-year-old sample, the NLLFS adolescent girls and boys were significantly older than their gender-matched peers in the NSFG at the time of their first heterosexual contact (see Table 4). Of those who were sexually active (NLLFS girls = 61.5% and NLLFS boys = 43.2%; NSFG girls = 64.1% and NSFG boys = 60.1%), NLLFS adolescent girls were significantly more likely to have had sexual contact with other girls, more likely to have used emergency contraception, and less likely to have used other forms of contraception, than NSFG adolescent girls. The NLLFS adolescent boys were significantly less likely to have been heterosexually active by the age of 17 than NSFG boys (see Table 4).

In a separate analysis of lifetime sexual behavior, the NLLFS adolescents were compared by gender. There were no significant differences in the percentages of NLLFS adolescent girls and boys who were sexually active, χ2(1, N = 76) = 2.55. There were also no significant gender differences in the percentages of NLLFS offspring who reported heterosexual, χ2(1, N = 76) = 1.96, or same-sex behavior, χ2(1, N = 75) = 1.90, nor in the mean age of their first heterosexual contact (t = 1.03).

Discussion

A key finding in the current study was that none of the NLLFS adolescents reported physical or sexual abuse by a parent or other caregiver. This finding contradicts the notion, offered in opposition to parenting by gay and lesbian people, that same-sex parents are likely to abuse their offspring sexually (Arkansas Department of Human Services, 2010; Falk, 1989; Ford, 2010; Golombok & Tasker, 1994; Patterson, 1992). The NLLFS adolescents’ lack of exposure to parent/caregiver abuse is consistent with their mothers’ reports at T4 (Gartrell et al., 2005), but contrasts with the self-reports of same-age adolescents in the U.S. National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence (Finkelhor, Ormrod, & Turner, 2009a; Finkelhor, Turner, Ormrod, & Hamby, 2009b; Finkelhor, Turner, Ormrod, Hamby, & Krack, 2009c). In the 17-year-old weighted subsample of the U.S. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention’s National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence (NATSCEV) (Finkelhor et al., 2009a, b, c), it was found that the lifetime rates of victimization by a parent or other caregiver were: 26.1% of adolescents had been physically abused and 8.3% sexually assaulted (D. Finkelhor, personal communication, March 13, 2010).

One possible explanation for the discrepancy between the NLLFS adolescents’ reports regarding abuse and the NATSCEV victimization data might be that most of the NLLFS adolescents grew up in households in which no adult males resided. Since the sexual abuse of children that occurs within the home is largely perpetrated by adult heterosexual males (Balsam et al., 2005; Turner, Finkelhor, & Ormrod, 2007; Peter, 2009; Putnam, 2003; Shusterman, Fluke, McDonald, & Associates, 2005; Zink, Klesges, Stevens, & Decker, 2009), growing up in lesbian-headed households may protect children and adolescents from these types of assault. In addition, corporal punishment is less commonly used by lesbian mothers as a disciplinary measure than by heterosexual fathers (Gartrell et al., 1999, 2000, 2005, 2006; Golombok et al., 2003). Research has shown an association between corporal punishment and other types of abuse (Gershoff, 2002; Sunday et al., 2008; Zolotor, Theodore, Chang, Berkoff, & Runyan, 2008). Because this is the first study to document lifetime parent/caregiver abuse through the self-reports of adolescents in planned lesbian families, it will be interesting to see whether future studies of same-sex parented families yield similar results.

Since the 1970s, when lesbians began to seek legal custody of their children at the time of divorce, expert witnesses have been asked whether children reared by same-sex parents might be more likely to identify as lesbian or gay in adulthood (Golombok et al., 2003; Tasker, 2005; United States District Court Northern District of California San Francisco Division, 2010). The present study found that nearly 20% of NLLFS adolescent girls rated themselves in the Kinsey bisexual spectrum, and none identified as predominantly-to-exclusively lesbian. The NLLFS adolescent girls were also more likely than the age-matched NSFG girls to have engaged in same-sex activity. Among 17-year-old NLLFS adolescent boys, 2.7% self-identified in the bisexual spectrum, and 5.4% as predominantly or exclusively homosexual. However, the NLLFS adolescent boys were no more likely to have engaged in same-sex behavior than were the boys in the NSFG sample.

The NLLFS adolescent girls’ Kinsey self-identifications and lifetime sexual experiences were consistent with Stacey and Biblarz’s (2001) and Biblarz and Stacey’s (2010) theory that the offspring of lesbian and gay parents might be more open to homoerotic exploration and same-sex orientation. Although the Golombok and Tasker (1996) study found no significant differences in the percentages of adults reared in lesbian and heterosexual households who reported same-sex attraction or orientation, the offspring of lesbian mothers were more likely to have engaged in same-sex behavior and to have grown up in households characterized by acceptance of lesbian and gay relationships (Golombok & Tasker, 1996; Tasker & Golombok, 1995). In the NLLFS, the adolescent offspring were born into families headed by mothers who were completely open about their lesbian orientation and active participants in the lesbian community (Bos, Gartrell, Peyser, & van Balen, 2008a; Bos, Gartrell, van Balen, Peyser, & Sandfort, 2008b; Gartrell & Bos, 2010; Gartrell et al., 1996, 1999, 2000, 2005, 2006). Perhaps this type of family environment made it more comfortable for adolescent girls with same-sex attractions to explore intimate relationships with their peers (Biblarz & Stacey, 2010; Stacey & Biblarz, 2001).

No significant differences were found between the NLLFS adolescent girls and boys on Kinsey self-identifications. However, although the numbers were small and the statistical power was weak, when the Kinsey Scale was collapsed into three categories (Kinsey 0–1, Kinsey 2–4, and Kinsey 5–6), the NLLFS adolescent girls were more likely than the NLLFS adolescent boys to rate themselves in the bisexual spectrum. Research has documented considerable fluidity in the development and expression of sexual orientation, particularly among young women (Diamond, 2005, 2007; Diamond & Butterworth, 2008). In a 10-year study of nonheterosexual women between the ages of 16 and 23, Diamond (2007) asked women how they identified in terms of their sexual orientation, including the terms “lesbian,” “bisexual,” “unlabeled,” or “heterosexual.” Diamond found over the course of 10 years, two-thirds of women had changed their identity label at least once, and one-quarter had changed their identity label more than once. The next NLLFS follow-up—at T6, when the offspring are 25 years old—will assess the stability of their sexual behavior and orientation over time.

The finding that the NLLFS sample was older than the NSFG sample at the time of first heterosexual experience may be associated with the absence of pregnancies and STIs among sexually-active NLLFS adolescents. Research suggests that the timing of heterosexual intercourse and the pace at which adolescents progress to more intimate behaviors are related to health outcomes (Cavazos-Rehg et al., 2008; de Graaf, Vanwesenbeeck, Meijer, Woertman, & Meeus, 2009). It is noteworthy that among the sexually active adolescent girls, even though more of the NSFG sample than the NLLFS sample used contraception, 18.2% (weighted data) of the sexually active NSFG girls had been pregnant. None of the NLLFS girls reported pregnancy, possibly due to their greater reliance on emergency contraception. The difference in the methods of contraception chosen by the two samples could be explained by numerous factors, including economic resources and parental, peer, and school support.

The rate of parental relationship dissolution was significantly higher in the NLLFS than in the NSFG. Although the offspring of divorced heterosexual parents have been shown to score lower on measures of emotional, academic, social, and behavioral adjustment (Amato, 2000; Emery, 1999), no differences in psychological adjustment were found when the 17-year-old NLLFS adolescents whose mothers had separated were compared with those whose mothers were still together (Gartrell & Bos, 2010). In addition, on the standardized Child Behavior Checklist, the daughters and sons of lesbian mothers were rated significantly higher in social, school/academic, and total competence, and significantly lower in social problems, rule-breaking, aggressive, and externalizing problem behavior than their peers in the normative sample of American youth (Gartrell & Bos, 2010). Whereas 65% of divorced American heterosexual mothers retain sole physical and legal custody of their children (Emery, Otto, & O’Donohue, 2005), custody was shared in nearly three-quarters of the NLLFS separated-parent families. Studies show that shared childrearing after parental relationship dissolution is associated with more favorable outcomes (Emery, 1994, in press). Consistent with the favorable psychological profiles of the NLLFS 17-year-olds, there were no reports of pregnancy or STIs among these offspring.

A strength of the NLLFS is that it is a prospective study, so the findings are not skewed by overrepresentation of families who volunteer when it is already clear that their offspring are functioning well. In addition, the dropout rate was very small. In most cases, the families that withdrew did so when the index children were less than 5 years old (Gartrell & Bos, 2010; Gartrell et al., 2000, 2006). Also, the T5 data were gathered through confidential adolescent self-reports, thereby increasing the likelihood of candid responses on sensitive topics, such as sexuality and victimization. Because the NLLFS is an ongoing longitudinal study, it is possible to assess consistency in behavior at different time intervals. In the current investigation, adolescents were only asked to provide information about their sexual identity on the Kinsey scale. At T6, the offspring will be asked to provide more detail about sexual identity, fantasy, and behavior in relation to orientation (Drummond, Bradley, Badali-Peterson, & Zucker, 2008; Green, 1987; Zucker & Bradley, 1995).

Despite these strengths, the NLLFS has several limitations. First, it is a nonrandom sample. At the time that the NLLFS began in the mid-1980s, due to the long history of discrimination against lesbian and gay people, the prospect of recruiting a representative sample of planned lesbian families was even more remote than it is today (Bos et al., 2007). A second limitation is that the NLLFS and NSFG were neither matched nor controlled for socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, or region of residence. An analysis of a more economically diverse sample would be an important contribution given that same-sex couples raising children are more likely to live in poverty and have lower household incomes than married, heterosexual couples raising children (Albelda, Badgett, Schneebaum, & Gates, 2009; Julien, Jouvin, Jodoin, l’Archeveque, & Chartrand, 2008). In addition, now that it is possible to obtain more information about sperm donors, future studies might benefit from exploring the association between the offspring’s sexual orientation and that of both parents. Finally, although the NLLFS is the largest, longest-running prospective study of planned lesbian families, the findings would be strengthened by replication in a larger sample.

The present study contributes a unique dimension to the literature on same-sex-parented families in reporting on the lifetime sexual experiences among 17-year-old adolescents who were conceived by donor insemination and born into planned lesbian families. To the best of our knowledge, the current investigation is the first to document parent/caregiver victimization experiences among adolescents reared by lesbian mothers. There was a noteworthy absence of parental/caregiver physical and sexual abuse in the self-reports of adolescents with lesbian mothers. Because victimization of children and adolescents is pervasive and can cause lasting physical, mental, and emotional harm (Finkelhor et al., 2009a, b, c; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2009), a more in-depth exploration of the ways that lesbian mothers protect their offspring from abuse is warranted. To the extent that these findings are replicated by other researchers, these data have implications for healthcare professionals, policymakers, social service agencies, child protection workers, and domestic violence advocates who seek family models in which violence does not occur.

References

Albelda, R., Badgett, M. V. L., Schneebaum, A., & Gates, G. J. (2009). Poverty in the lesbian, gay, and bisexual community. The Williams Institute. Retrieved from http://www.law.ucla.edu/williamsinstitute/pdf/LGBPovertyReport.pdf.

Amato, P. R. (2000). The consequences of divorce for adults and children. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 1269–1287.

Arkansas Department of Human Services. (2010). Cole v. Arkansas. Retrieved from http://www.aclu.org/files/assets/Intervenors_SJ_reply_brief.PDF.

Bailey, J. M., Dunne, M. P., & Martin, N. G. (2000). Genetic and environmental influences on sexual orientation and its correlates in an Australian twin sample. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 524–536.

Balsam, K. F., Levahot, K., Beadnell, B., & Circo, E. (2010). Childhood abuse and mental health indicators among ethnically diverse lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78, 459–468.

Balsam, K. F., Rothblum, E. D., & Beauchaine, T. P. (2005). Victimization over the lifespan: A comparison of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual siblings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 477–487.

Biblarz, T., & Stacey, J. (2010). How does the gender of parents matter? Journal of Marriage and the Family, 72, 3–22.

Bos, H. M. W., Gartrell, N. K., Peyser, H., & van Balen, F. (2008a). The USA National Longitudinal Lesbian Family Study: Homophobia, psychological adjustment, and protective factors. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 12, 455–471.

Bos, H. M. W., Gartrell, N. K., van Balen, F., Peyser, H., & Sandfort, T. G. M. (2008b). Children in planned lesbian families: A cross-cultural comparison between the USA and the Netherlands. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 78, 211–219.

Bos, H. M. W., & Sandfort, T. G. M. (2010). Children’s gender identity in lesbian and heterosexual two-parent families. Sex Roles, 62, 114–126.

Bos, H. M. W., van Balen, F., & Van den Boom, D. C. (2007). Child adjustment and parenting in planned lesbian-parent families. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 77, 38–48.

Cavazos-Rehg, P. A., Spitznagel, E. L., Bucholz, K. K., Nurnberger, J., Edenberg, H., Kramer, J. R., et al. (2008). Predictors of sexual debut at age 16 or younger. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39, 664–673.

Committee on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual Concerns, Committee on Children, Youth, Families, Committee on Women in Psychology. (2005). Lesbian and gay parenting. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

de Graaf, H., Vanwesenbeeck, I., Meijer, S., Woertman, L., & Meeus, W. (2009). Sexual trajectories during adolescence: Relation to demographics characteristics and sexual risk. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38, 276–282.

Diamond, L. M. (2005). A new view of lesbian subtypes: Stable versus fluid identity trajectories over an 8-year period. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 29, 119–128.

Diamond, L. M. (2007). A dynamical systems approach to the development and expression of female same-sex sexuality. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2, 142–161.

Diamond, L. M., & Butterworth, M. (2008). Questioning gender and sexual identity: Dynamic links over time. Sex Roles, 59, 365–376.

Drummond, K. D., Bradley, S. J., Badali-Peterson, M., & Zucker, K. J. (2008). A follow-up study of girls with gender identity disorder. Developmental Psychology, 44, 34–45.

Emery, R. E. (1994). Renegotiating family relationships. New York: Guilford.

Emery, R. E. (1999). Marriage, divorce, and children’s adjustment. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Emery, R. E. (in press). Renegotiating family relationships (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford.

Emery, R. E., Otto, R. K., & O’Donohue, W. T. (2005). A critical assessment of child custody evaluations: Limited science and a flawed system. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 6, 1–29.

Falk, P. J. (1989). Lesbian mothers: Psychosocial assumptions in family law. American Psychologist, 44, 941–947.

Faulkner, A. H., & Cranston, K. (1998). Correlates of same-sex sexual behavior in a random sample of Massachusetts high school students. American Journal of Public Health, 88, 262–266.

Finkelhor, D., Ormrod, R. K., & Turner, H. A. (2009a). Lifetime assessment of poly-victimization in a national sample of children and youth. Child Abuse and Neglect, 33, 403–411.

Finkelhor, D., Turner, H., Ormrod, R., & Hamby, S. L. (2009b). Violence, abuse, and crime exposure in a national sample of children and youth. Pediatrics, 124, 1411–1423.

Finkelhor, D., Turner, H., Ormrod, R. K., Hamby, S. L., & Krack, K. (2009c, October). Children’s exposure to violence: A comprehensive national survey. Juvenile Justice Bulletin, 1–11.

Ford, C. (2010). Family First worth fighting. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved from http://www.abc.net.au/unleashed/stories/s2979646.htm.

Fulcher, M., Sutfin, E. L., & Patterson, C. (2008). Individual differences in gender development: Associations with parental sexual orientation, attitudes, and division of labor. Sex Roles, 58, 330–341.

Gartrell, N., Banks, A., Hamilton, J., Reed, N., Bishop, H., & Rodas, C. (1999). The National Lesbian Family Study: 2. Interviews with mothers of toddlers. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 69, 362–369.

Gartrell, N., Banks, A., Reed, N., Hamilton, J., Rodas, C., & Deck, A. (2000). The National Lesbian Family Study: 3. Interviews with mothers of five-year-olds. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 70, 542–548.

Gartrell, N., & Bos, H. M. W. (2010). The US National Longitudinal Lesbian Family Study: Psychological adjustment of 17-year-old adolescents. Pediatrics, 126, 1–9.

Gartrell, N., Deck, A., Rodas, C., Peyser, H., & Banks, A. (2005). The National Lesbian Family Study: 4. Interviews with the 10-year-old children. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 75, 518–524.

Gartrell, N., Hamilton, J., Banks, A., Mosbacher, D., Reed, N., Sparks, C. H., et al. (1996). The National Lesbian Family Study: 1. Interviews with prospective mothers. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 66, 272–281.

Gartrell, N., Rodas, C., Deck, A., Peyser, H., & Banks, A. (2006). The National Lesbian Family Study: 5. Interviews with mothers of ten-year-olds. Feminism and Psychology, 16, 175–192.

Gershoff, E. T. (2002). Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 539–579.

Goldberg, A. E. (2010). Lesbian and gay parents and their children: Research on the family life cycle. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Golombok, S. (2000). Parenting: What really counts? Philadelphia: Taylor & Francis.

Golombok, S. (2007). Research on gay and lesbian parenting: An historical perspective across 30 years. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 3, xxi–xxvii.

Golombok, S., & Badger, S. (2010). Children raised in mother-headed families from infancy: A follow-up of children of lesbian and heterosexual mothers, at early adulthood. Human Reproduction, 25, 150–157.

Golombok, S., Perry, B., Burston, A., Murray, C., Mooney-Somers, J., Stevens, M., et al. (2003). Children of lesbian parents: A community study. Developmental Psychology, 39, 20–33.

Golombok, S., & Tasker, F. (1994). Children in lesbian and gay families: Theories and evidence. Annual Review of Sex Research, 4, 73–100.

Golombok, S., & Tasker, F. (1996). Do parents influence the sexual orientation of their children? Findings from a longitudinal study of lesbian families. Developmental Psychology, 32, 3–11.

Golombok, S., Tasker, F., & Murray, C. (1997). Children raised in fatherless families from infancy: Family relationships and the socioemotional development of children of lesbian and single heterosexual mothers. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38, 783–791.

Green, R. (1987). The “sissy boy syndrome” and the development of homosexuality. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Hines, M., Brook, C., & Conway, G. S. (2004). Androgen and psycho-sexual development: Core gender identity, sexual orientation and recalled childhood gender role behavior in women and men with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH). Journal of Sex Research, 41, 75–81.

Hollingshead, A. B. (1975). Four factor index of social status. Unpublished manuscript, Yale University, New Haven, CT.

Jenny, C., Roesler, T. A., & Poyer, K. L. (1994). Are children at risk for abuse by homosexuals? Pediatrics, 94, 41–44.

Julien, D., Jouvin, E., Jodoin, E., l’Archeveque, A., & Chartrand, E. (2008). Adjustment among mothers reporting same-gender sexual partners: A study of a representative population sample from Quebec Province (Canada). Archives of Sexual Behavior, 37, 864–876.

Kendler, K. S., Thornton, L. M., Gilman, S. E., & Kessler, R. C. (2000). Sexual orientation in a U.S. national sample of twin and non-twin sibling pairs. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 1843–1846.

Langstrom, N., Rahman, Q., Carlstrom, E., & Lichtenstein, P. (2010). Genetic and environmental effects on same-sex sexual behavior: A population study of twins in Sweden. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39, 75–80.

MacCallum, F., & Golombok, S. (2004). Children raised in fatherless families since infancy: A follow-up of children of single and heterosexual mothers at early adolescence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45, 1407–1419.

Patterson, C. J. (1992). Children of lesbian and gay parents. Child Development, 63, 1025–1042.

Perrin, E. (2002). Sexual orientation in child and adolescent health care. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Perrin, E. C., & American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child, Family Health. (2002). Technical report: Coparent or second-parent adoption by same-sex parents. Pediatrics, 109, 341–344.

Peter, T. (2009). Exploring taboos: Comparing male- and female-perpetrated child sexual abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24, 1111–1128.

Putnam, F. W. (2003). Ten-year research update review: Child sexual abuse. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 42, 269–278.

Sell, R. L. (1997). Defining and measuring sexual orientation: A review. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 26, 643–658.

Shusterman, G., Fluke, J., McDonald, W. R., & Associates. (2005). Male perpetrators of child maltreatment: Findings from NCANDS. Retrieved from United States Department of Health and Human Services website: http://aspe.hhs.gov/hsp/05/child-maltreat/.

Stacey, J., & Biblarz, T. (2001). (How) does the sexual orientation of parents matter? American Sociological Review, 66, 159–183.

Sunday, S., Labruna, V., Kaplan, S., Pelcovitz, D., Newman, J., & Salzinger, S. (2008). Physical abuse during adolescence: Gender differences in the adolescents’ perceptions of family functioning and parenting. Child Abuse and Neglect, 32, 5–18.

Supreme Court of Iowa. (2009). Varnum v. Brian. Retrieved from http://www.iowacourts.gov/Supreme_Court/Recent_Opinions/20090403/07-1499.pdf.

Tasker, F. (2005). Lesbian mothers, gay fathers and their children: A review. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 26, 224–240.

Tasker, F., & Golombok, S. (1995). Adults raised as children in lesbian families. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 65, 203–215.

Thompson, J. M. (2002). Mommy queerest: Contemporary rhetorics of lesbian maternal identity. Boston, MA: University of Massachusetts Press.

Turner, H. A., Finkelhor, D., & Ormrod, R. (2007). Family structure variations in patterns and predictors of child victimization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 77, 282–295.

United States District Court Northern District of California San Francisco Division. (2010). Perry et al. v. Schwarzenegger et al. Brief of Amici Curiae NDCA Case no. 09-CV-2292 VRW.

U.S. Department of Health, Human Services. (2005). National survey of family growth. Cycle 6: 2002 ACASI File. User’s guide and documentation. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics.

U.S. Department of Health, Human Services. (2006). National survey of family growth. Cycle 6: Sample design, weighting, imputation, and variance estimation. Vital Health Statistics, 142, 1–82.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2009). Child welfare information gateway. Long-term consequences of child abuse and neglect. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2008. Retrieved from http://www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/factsheets/long_term_consequences.cfm.

Vanfraussen, K., Ponjaert-Kristoffersen, I., & Brewaeys, A. (2002). What does it mean for youngsters to grow up in a lesbian family created by means of donor insemination? Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 20, 237–252.

Vanfraussen, K., Ponjaert-Kristoffersen, I., & Brewaeys, A. (2003). Family functioning in lesbian families created by donor insemination. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 73, 78–90.

Wainright, J. L., Russell, S. T., & Patterson, C. J. (2004). Psychosocial adjustment, school outcomes, and romantic relationships of adolescents with same-sex parents. Child Development, 75, 886–1898.

Wilson, H. W., & Widom, C. S. (2010). Does physical abuse, sexual abuse, or neglect in childhood increase the likelihood of same-sex sexual relationships and cohabition? A prospective 30-year follow-up. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39, 63–74.

Zink, T., Klesges, L., Stevens, S., & Decker, P. (2009). Trauma symptomatology, somatization, and alcohol abuse: Characteristics of childhood sexual abuse associated with the development of a sexual abuse severity score. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24, 537–546.

Zolotor, A. J., Theodore, A. D., Chang, J. J., Berkoff, M. C., & Runyan, D. K. (2008). Speak softly—and forget the stick: Corporal punishment and child physical abuse. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 35, 364–369.

Zucker, K. J., & Bradley, S. J. (1995). Gender identity disorder and psychosexual problems in children and adolescents. New York: Guilford Press.

Acknowledgments

The NLLFS has been supported in part by grants from The Gill Foundation, the Lesbian Health Fund of the Gay Lesbian Medical Association, Horizons Foundation, and The Roy Scrivner Fund of the American Psychological Foundation. The Williams Institute at UCLA School of Law has provided grant and personnel support to the NLLFS. Funding sources played no role in the design or conduct of the study; the management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; nor in the preparation, review, or approval of the article. We thank Heidi Peyser, M.A., Amalia Deck, MSN, Evalijn Draijer, M.S., Carla Rodas, MPH, Loes van Gelderen, M.S., Anjani Chandra, Ph.D., David Finkelhor, Ph.D., Gladys Martinez, Ph.D., Esther Rothblum, Ph.D., and The Williams Institute at UCLA School of Law.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Gartrell, N.K., Bos, H.M.W. & Goldberg, N.G. Adolescents of the U.S. National Longitudinal Lesbian Family Study: Sexual Orientation, Sexual Behavior, and Sexual Risk Exposure. Arch Sex Behav 40, 1199–1209 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-010-9692-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-010-9692-2