Abstract

Daily oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is the use of antiretroviral drugs by HIV-negative people to prevent HIV infection. WHO released new guidelines in 2015 recommending PrEP for all populations at substantial risk of HIV infection. To prepare these guidelines, we conducted a systematic review of values and preferences among populations that might benefit from PrEP, women, heterosexual men, young women and adolescent girls, female sex workers, serodiscordant couples, transgender people and people who inject drugs, and among healthcare providers who may prescribe PrEP. A comprehensive search strategy reviewed three electronic databases of articles and HIV-related conference abstracts (January 1990–April 2015). Data abstraction used standardised forms to categorise by population groups and relevant themes. Of 3068 citations screened, 76 peer-reviewed articles and 28 conference abstracts were included. Geographic coverage was global. Most studies (N = 78) evaluated hypothetical use of PrEP, while 26 studies included individuals who actually took PrEP or placebo. Awareness of PrEP was low, but once participants were presented with information about PrEP, the majority said they would consider using it. Concerns about safety, side effects, cost and effectiveness were the most frequently cited barriers to use. There was little indication of risk compensation. Healthcare providers would consider prescribing PrEP, but need more information before doing so. Findings from a rapidly expanding evidence base suggest that the majority of populations most likely to benefit from PrEP feel positively towards it. These same populations would benefit from overcoming current implementation challenges with the shortest possible delay.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is the use of antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) by HIV-negative people to prevent HIV infection. In 2010, the first randomized clinical trial results were released showing effectiveness of oral PrEP (tenofovir/emtricitabine) among men who have sex with men [1]. Since then, several more clinical trials have been conducted in different populations, and together these studies suggest PrEP is highly effective if taken regularly [2].

The World Health Organization (WHO) released a first recommendation on the use of PrEP in 2012 [3] for men who have sex with men and serodiscordant couples in the context of demonstration projects to explore strategies for implementation. In 20 [4, 14] WHO recommended offering PrEP for men who have sex with men (MSM) as an additional prevention option. In September 2015, WHO recommended offering PrEP for all persons at substantial risk of HIV infection [5].

In developing evidence-based clinical guidelines, WHO considers the values and preferences of users. For PrEP, as for many other biomedical interventions, understanding the knowledge of potential users, their willingness to use it, and the potential barriers and facilitators to its uptake is critical to its success. Clinical trials demonstrate that adherence to PrEP is significantly associated with effectiveness [2]. Other challenges to the successful implementation of PrEP programs can also be identified and addressed by understanding potential users’ perspectives.

To prepare the 2015 WHO guidance, we conducted a systematic review of the literature on the values and preferences around PrEP across groups that might benefit from it, including heterosexual males, females, and transgender persons, and healthcare providers who may prescribe PrEP.

Method

Inclusion Criteria

We included studies in the review if they met the following criteria: (i) examined participants’ views of PrEP, willingness to take PrEP, concerns about PrEP, or values around PrEP, (ii) presented primary data (qualitative or quantitative), and (iii) published as a peer-reviewed journal article or conference abstract. We excluded studies conducted only among men who have sex with men, because a strong WHO recommendation already existed for this population [4]. Think pieces, review articles and consultation reports were not included in the main analysis, and were considered only to verify consistency of findings.

Search Strategy

We searched PubMed, CINAHL, and EMBASE using the date ranges January 1, 1990 to April 15, 2015. We used the following search terms across all databases: (“pre-exposure prophylaxis” or “preexposure prophylaxis” or “antiretroviral prophylaxis” or “preexposure chemoprophylaxis” or chemoprevention or PrEP) AND (HIV OR AIDS). We also searched abstracts from the following conferences: International AIDS Conference (IAC), Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment, and Prevention (IAS), and Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI). Only abstracts available electronically were included (CROI 2014–2015, IAS/IAC 2006–2014).

Data Extraction and Management

All references identified through the search process underwent eligibility screening. Initial screening of database and conference abstract search results was done by one person to remove clearly irrelevant articles. A second screening was then conducted by two reviewers independently with resolution of discrepancies through discussion. Papers meeting the inclusion criteria were obtained in full-text form. All studies were reviewed and key data extracted by a single reviewer using standardized forms. Data included: citation information, population studied, region/country, sample size, key findings, and whether the study was linked to a clinical trial, demonstration project, open label study, family planning clinic, or early roll-out.

We separated findings by the following populations (not mutually exclusive): (1) women, (2) heterosexual men, (3) young women and adolescent girls, (4) female sex workers, (5) serodiscordant couples, (6) transgender people, (7) people who inject drugs, and (8) healthcare providers.

Findings from each study were categorized into five themes to evaluate likelihood of PrEP uptake and factors that may impact uptake and use: (1) awareness of PrEP, (2) willingness to use PrEP, (3) barriers and facilitators to PrEP use, (4) risk compensation, and (5) healthcare providers’ opinions.

Results

Description of Included Studies

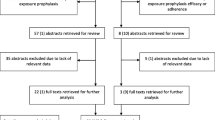

Appendix Fig 1 presents the disposition of citations through the search and screening process. Of 3068 citations identified through the initial search, 76 peer-reviewed articles and 28 conference abstracts met our inclusion criteria [6–109].

Included studies covered a wide range of population groups and geographic areas (Appendix Table 1). There were more quantitative studies (N = 68) than qualitative (N = 24) or mixed methods (N = 12). Most studies (N = 78) evaluated hypothetical PrEP use or perspectives among people not currently using PrEP, while 26 included people actually taking PrEP or placebo. In this paper, findings reported pertaining to specific studies refer to hypothetical PrEP use unless otherwise specified. In several instances, multiple articles/abstracts appeared to come from the same studies, but without overlapping data. Because it was difficult to clearly identify the number of studies, we refer to articles/abstracts below. In a number of instances, we chose not to list all studies that addressed each point, but picked the ones that best represented the overall themes that emerged, and whenever possible, we selected the larger, higher quality studies, or the studies covering actual use. Note should be made as well that two articles were written in Chinese. The authors based their findings on the English abstract but asked a Chinese speaker to verify that no major inconsistencies existed between the abstract and the body of the Chinese paper.

Awareness of and Willingness to Use PrEP

Studies generally reported solid support for PrEP across most populations; however, many studies described a significant lack of knowledge about PrEP and actual use of PrEP remained anecdotal outside of trials. Once the concept of PrEP was introduced, a clear majority of participants across studies welcomed PrEP as a potentially important prevention option for themselves and for others.

Women

Among women outside clinical trials or demonstration projects exploring strategies for implementation, awareness of PrEP ranged from ‘almost none’ [7] to 8% having heard about PrEP [102]. One US study mentioned that women were ‘angry’ about not having heard of PrEP [8]. Studies addressing willingness to use PrEP included approximately 15,000 women; willingness to use PrEP ranged from 54% [103] among a group of white Americans to 87% [56] among 5180 women in Kenya. Outside that range, only one study found low interest in PrEP of 20% [43] in a small subgroup of Caribbean women living in the US.

Theoretical interest in PrEP among women was supported by experience from the HPTN 067/ADAPT open-label study. 179 women were given the option to take PrEP, and, knowing it was the active drug, the majority did choose take it [9].

Adolescent Girls/Young Women

Just five studies were conducted among adolescent girls and young women. One US study reported that 64% of 595 young women aged 20–29 said they would take PrEP [72]. Another study with Kenyan and South African girls and young women aged 14–24 found that all participants showed strong interest in PrEP [46]. A third study showed participants would be willing to take PrEP if it was provided for free in the US, even if re-testing every 3 months was required [81].

Serodiscordant Couples

Studies reported little (3% [55]) to no [76] knowledge of PrEP amongst SDC. Across studies, the majority of serodiscordant couples showed clear willingness to use PrEP, whether to protect seronegative partners or for safer conception. One Chinese study found up to 85% serodiscordant couples were willing to use PrEP [55].

Within the experienced and well-informed Kenyan population of the Partners PrEP clinical trial, one study showed 90% of participants would be willing to use PrEP on a long-term basis against 58% for ‘treatment as prevention’ (TasP), though often preferring the option they controlled [31]. Another Kenyan study, however, found hypothetical TasP to be the more acceptable strategy [23].

Early signs of actual uptake in the general population in the UK were observed in a fertility clinic, where 13 couples offered PrEP chose to take it and 4 declined [100]. Opposite results were seen in South Africa where only 2 out of 16 participants (male and female) elected to take PrEP for safer conception [76].

Female Sex Workers

Three Chinese studies reported on PrEP awareness among a total of 2778 female sex workers, with awareness ranging from 12 to 17%. [65, 106, 108] Once the concept of PrEP was introduced, female sex workers across the world expressed strong interest in using PrEP across seven studies (N = 4809 total participants) [18, 24, 46, 65, 68, 106, 108]. Interest rose across these studies over time, in the range of 61–69% in 2010 –2012 [18, 65, 68, 108] up to 86% in 2014 [106].

People Who Inject Drugs

Studies indicated that people who inject drugs moderately support PrEP as an additional choice to prevent sexual transmission of HIV. One US study showed 58% of people who inject drugs would use PrEP if it were 90% effective [84]. In Canada, 35% said they would be willing to use PrEP, with higher rates of acceptance among women (42%); younger age, no regular employment, requiring help injecting, engaging in sex work, and reporting multiple recent sexual partners were positively associated with willingness to use PrEP [20]. A small group in a Ukraine study showed higher rates of 86% probable or definite willingness [18].

Transgender People

A Thai study reported high PrEP awareness among transgender people (66%); 37% of participants were ‘very likely’ to use PrEP with 50% hypothetical efficacy, increasing to 62% if they had insurance coverage [105]. A majority of transgender people in a small study in the US indicated they would use PrEP [96]. In Peru, transgender people and MSM (results non-stratified) found PrEP ‘highly acceptable’, particularly among those at highest risk [64].

Heterosexual Men

We found limited literature on men outside of studies with men who have sex with men, drug users, or serodiscordant couples. One study examined theoretical acceptability of PrEP among truckers and their helpers/cleaners in India with 1602 participants; acceptability of PrEP was 86% [66, 75]. However, a separate paper reported that in-depths interviews with 90 truckers from the same area showed low levels of 33% initial commitment toward PrEP. [74].

Barriers and Facilitators

The four most commonly cited barriers to PrEP identified in the studies across all risk groups were concerns about safety, side effects, cost and effectiveness. Participants had concerns about safety and whether it could affect their health and well-being, since PrEP involves taking a pill while one is healthy. They were also concerned about potential side effects in the context of other drugs and/or alcohol and/or recreational drugs. Concerns were frequently raised as to how much PrEP would cost, and whether the person using PrEP would have to make a financial contribution. As can be expected, interest in PrEP declines when there is any payment on the part of the user.

Other barriers regularly cited by most risk groups were stigma surrounding HIV and antiretroviral drugs (ARV); low risk perception, including both personal risk and partner risk; the perception that pills are only for sick people; and education level. Facilitators of PrEP use included partner and peer support, especially if peers also knew about PrEP; and discreteness of a pill and the ability to have control over this prevention option, especially in the context of difficulties negotiating condom use.

Women

One large US study of 1509 women recorded a higher likelihood of PrEP use among women at high HIV risk with less education, more sexual partners, and provider and peer norms supporting PrEP [103]. The FEM-PrEP clinical trial where PrEP was actually dispensed attributed in part its failure to demonstrate PrEP effectiveness to factors such as unacceptability of a daily pill and negative influence from peers, partners and the community which influenced women not to actually ingest the pills [13]. On the other hand, risk reduction and adherence strategies consisting of external cues, reminders and support facilitated its use [12].

Adolescent Girls/Young Women

Young women’s willingness to take PrEP was influenced by their social context. One large US study found young women aged 20–29 were likely to experience stronger social influences (healthcare providers’ recommendation to take PrEP or belief peers would take PrEP) on PrEP uptake than older women, and 77% expected they could adhere to a daily regimen [72]. Another study described young women’s concerns about the difficulty negotiating PrEP use with their partners, and adolescent girls and young women appreciated the ‘privacy’ of a pill [46].

Serodiscordant Couples

A Kenyan study found a significant concern among serodiscordant couples that ARVs should not be taken by HIV-negative people, while HIV-positive individuals felt guilty that their HIV-negative partners had to take ARVs because of their own infection [23]. Opinions about the effect of stigma on PrEP use were mixed [23, 55]. Partner support was also considered important in the Partners PrEP study where participants took PrEP, where it was seen as ‘preserving’ the relationship [95]. On the other hand, in the VOICE trial the lack of men’s acceptance of PrEP pertained to men’s unwillingness to accept potential shifts in their relationship power, and may have negatively affected women’s adherence to PrEP [58].

Female Sex Workers

In a Phase I study in Kenya with actual PrEP use, female sex workers perceived it positively as a female-controlled HIV prevention option, though they saw incompatibilities between regular pill taking and irregular lifestyles and feared being perceived as HIV positive [90]. One study called for effective follow-up systems to support adherence to clinic and testing visits, as well as schedule cards, home visits and calls [47]. High alcohol consumption by some sex workers was also a repeated concern [46]. Three Chinese studies found that the higher a sex worker assessed her own HIV risk, the more likely she was to find PrEP acceptable [68, 106, 108].

People who Inject Drugs

People who inject drugs considered cost and daily dosing requirements as potential barriers to uptake. Blood tests, continued condom use, clinician visits, and regular HIV tests were seen as smaller barriers [84].

Transgender People

Cost affected willingness to use PrEP among transgender people in two studies in Peru, [24] where out-of-pocket cost had the greatest impact on decision making, followed by effectiveness, side effects, dispensing location and person [15]. Concerns were expressed about rejection, discrimination and lack of sensitivity from healthcare providers dispensing PrEP [24, 62]. Nearly three quarters of Thai respondents were concerned about drug interaction with hormone replacement therapy and other medications [105].

Risk Compensation

Many studies considered the potential for risk compensation through increased number of partners and decreased condom use. Across studies, the majority of participants did not anticipate hypothetical PrEP use would lead to increased risk behaviours. These findings are consistent with results from a meta-analysis of PrEP outcomes, which showed no significant effect on sexual behaviour with PrEP use [2]. Some specific groups, however, showed differing results as described below.

Women

In one US study, 26% of 1543 respondents indicated that taking PrEP could result in a decrease in condom use [103]. On the other hand, within the small double blinded clinical trial of 400 women in Ghana where PrEP was actually taken, results showed no increase in risk behaviour overall, and a decrease in number of sexual partners and rate of unprotected sex acts [30].

Serodiscordant Couples

Just 3% of Chinese participants expected they would increase their number of partners if they were taking PrEP, while 12% reported they would decrease condom use [55]. In Kenya, 25% of respondents indicated a desire to stop using condoms if taking PrEP [23].

Female Sex Workers

Some sex workers raised concerns that their colleagues might see PrEP as an opportunity to forego condoms to increase earnings [46].

Adolescent Girls/Young Women

One study found 20% of young women expected to use condoms less frequently if they took PrEP [72].

Transgender People

One study found anecdotally that condom use may decrease with PrEP [24].

Healthcare Providers

Across 20 studies and 6 abstracts, providers reported on their knowledge of PrEP. An increase in PrEP awareness over time was observed [101]. It increased up to 90% familiarity with PrEP in 2013 [87] in a survey amongst HIV specialists and HIV healthcare providers after the iPrEx study results became available. Despite this increase, providers across the globe remain reluctant to provide PrEP. Between 9% [35, 36] and 19% [87] of clinicians had prescribed PrEP and 22% of pharmacists [78] had dispensed it. Two studies showed that the likelihood of prescribing PrEP increased when providers cared for more HIV-positive patients, [35] had higher PrEP knowledge, were older, and believed PrEP would empower women.

Most healthcare providers considered PrEP primarily for serodiscordant couples, although some recognised that other groups would benefit. In Italy, 70% of HIV specialists said they would prescribe PrEP, 64% to serodiscordant couples but also 56% to other people at risk, [67] while in Argentina, 40% would consider prescribing PrEP to serodiscordant couples and 35% to sex workers [82]. Medical and counselling service providers supported PrEP in outpatient drug treatment clinics [83].

A common theme across studies was that knowledge of and demand for PrEP should be increased through providing information to healthcare providers, [79] community education campaigns, [6] normative guidance, [79] and local implementation guidelines [85].

Discussion

Our review identified strong interest and support for PrEP use amongst most populations at risk of HIV infection, and lesser (though still fairly high) interest among people who inject drugs. Notably, literature on heterosexual men, transgender people, adolescent girls and young women, and people who inject drugs is limited, thus calling for more research. Positive responses found in studies evaluating hypothetical PrEP use were supported by studies examining actual use and uptake. Nonetheless, many potential PrEP users and healthcare providers lack basic knowledge of PrEP. Additional efforts are needed to raise awareness about PrEP benefits and ensure more accurate HIV risk perception, especially among younger populations.

The four key barriers to PrEP uptake identified in this review—safety, side effects, cost and effectiveness—can all be addressed through strong programs. Evidence regarding the safety and effectiveness of PrEP is mounting, most side effects associated with oral PrEP diminish after the first month, and costs should drop with increased PrEP availability and insurance coverage. Population- and setting-specific solutions could address other barriers and leverage facilitators to PrEP. For example, late-night clinics may help reach sex workers with irregular schedules [47]. Concerns about potential drug interaction with hormone replacement therapy should be amenable to information campaigns. While some respondents found daily dosing ‘incompatible with a lifestyle where most people ‘live in the moment,’ [24] one study found that over 50% of transgender people were using other daily medications, allowing integration of PrEP into their routine [105]. Further research is however needed to evaluate what best solutions may be to tackle each of these challenges.

Findings from this review suggest limited concern around risk compensation. This is supported by behavioural and reproductive health outcomes from PrEP clinical trials [2] and emerging ethnographic research within the iPrEx open label study (OLE) and the San Francisco PrEP demonstration project that suggests actual use of PrEP may encourage sexual mindfulness and lead to safer behaviour [110, 111]. However, risk compensation may be a concern for specific sub-populations, such as young women, transgender people and sex workers. Those who are highly motivated and adhere to PrEP may not require additional HIV prevention strategies, but may still need protection against pregnancy or other sexually transmitted infections.

Although potential PrEP users expressed interest and enthusiasm about PrEP in the studies considered in this paper, concerns around PrEP undermining existing successful prevention programmes for sex workers were noted by international panels of advocates in settings where comprehensive condom programing is well established and HIV incidence is low [112, 113]. Similar concerns have been raised in using PrEP among people who inject drugs to prevent parenteral HIV transmission, as harm reduction programmes are highly successful in preventing HIV transmission and have broader health benefits [114, 115].

Findings from this review must be seen in light of its limitations. Given a short timeline to provide results for the WHO guideline development process, only one person extracted data. Although we consider our search to be comprehensive, we may still have missed some relevant articles. We note that the current evidence base includes more articles about hypothetical PrEP use than about actual experiences with PrEP. However, as PrEP use expands globally, more studies will likely report actual users’ experiences. We encourage future researchers to consider the gaps identified through this review as opportunities for future research into PrEP values and preferences among diverse populations and in diverse implementation settings.

Conclusions

PrEP is increasingly recognised as a critical component of comprehensive HIV prevention programming. This systematic literature review on values and preferences confirms that many potential users are interested in PrEP and willing to take it. While multiple implementation challenges remain for countries as they consider the introduction of oral PrEP as an HIV prevention tool, a clearer understanding of how potential users perceive PrEP will enhance the service delivery of PrEP across countries. At risk populations will greatly benefit from overcoming these programming issues with the shortest possible delays.

References

Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–99.

Fonner VA, Dalglish S, Kennedy CE, et al. Oral tenofovir-based HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for all populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis of effectiveness, safety, behavioural, and reproductive health outcomes. AIDS. 2016;30(12):1973–83.

World Health Organization. Guidance on pre-exposure oral prophylaxis (PrEP) for serodiscordant couples, men and transgender women who have sex with men at high risk of HIV. Geneva: WHO; 2012.

World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care for key populations. Geneva: WHO; 2014.

World Health Organization. Guideline on when to start antiretroviral therapy and on pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV. Geneva: WHO; 2015.

Arnold EA, Hazelton P, Lane T, et al. A qualitative study of provider thoughts on Implementing pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in clinical settings to prevent HIV infection. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(7):e40603.

Auerbach JD, Banyan A, Riordan M. Will and should women in the U.S. use PrEP? Findings from a focus group study of at-risk, HIV-negative women in Oakland, Memphis, San Diego and Washington, D.C. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;15:193.

Auerbach JD, Kinsky S, Brown G, Charles V. Knowledge, attitudes, and likelihood of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use among US women at risk of acquiring HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2015;29(2):102–10.

Bekker L-G, Hughes J, Amico R, et al. HPTN 067/ADAPT Cape Town: a comparison of daily and nondaily PrEP dosing in African Women. Paper presented at: CROI 2015. Seattle, 2015 [Abstract no. 978LB].

Brubaker SG, Darbes L, Bukusi E, Cohen CR. Theoretical acceptability of four interventions to reduce the risk of HIV transmission among HIV discordant couples trying to conceive. Rome: International AIDS Society; 2011.

Castro JG, Jones DL, Weiss SM. STD patients’ preferences for HIV prevention strategies. HIV/AIDS (Auckland, NZ). 2014;6:171–5.

Corneli A, Perry B, Agot K, Ahmed K, Malamatsho F, Van Damme L. Facilitators of adherence to the study pill in the FEM-PrEP clinical trial. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(4):e0125458.

Corneli A, Perry B, McKenna K, et al. Participants’ explanations for nonadherence in the FEM-PrEP clinical trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;71(4):452–61.

Corneli AM, Agot K, Ahmed K, Olang’o L, Makatu S, Lombaard J, Malahleha M, Van Damme L, FEM-PrEP Study Group. The association between risk perception and adherence in the FEM-PrEP clinical trial. 7th IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis and Treatment. Kuala Lumpur, 2013 [Abstract no. MOLBPE28].

Cunningham WE, Galea JT, Kinsler JJ, et al. The acceptability of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention in Lima, Peru. AIDS 2008—17th International AIDS Conference. Mexico, 2008 [Abstract no. WEPE0260].

Desai M, Gafos M, McCormack S, Nardone A. Healthcare workers knowledge of, attitudes to and practice of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV. HIV Med. 2014;15:28.

Dunkle K, Wingood G, Camp C, DiClemente R. Intention to use pre-exposure prophylaxis among African-American and white women in the United States: results from a national telephone survey. Paper presented at: 17th International AIDS Conference. Mexico, 2008.

Eisingerich AB, Wheelock A, Gomez GB, Garnett GP, Dybul MR, Piot PK. Attitudes and acceptance of oral and parenteral HIV preexposure prophylaxis among potential user groups: a multinational study. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(1):e28238.

Engeran-Cordova W. ea. Community survey indicates low viability of PrEP for HIV prevention. Paper presented at: XIX International AIDS Conference. Washington, 2012 [Abstract WEPE265].

Escudero DJ, Kerr T, Wood E, et al. Acceptability of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among people who inject drugs (PWID) in a Canadian setting. AIDS Behav. 2014;19(5):752–7.

Flash CA, Stone VE, Mitty J, Mimiaga M, Hall KT, Krakower D, Mayer KH. Acceptability of oral or vaginal HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among at-risk black women in the United States. Paper presented at: XIX International AIDS Conference. Washington, 2012 [Abstract LBPE41—Poster Exhibition].

Flash CA, Stone VE, Mitty JA, et al. Perspectives on HIV prevention among urban black women: a potential role for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2014;28(12):635–42.

Fowler N, Arkell P, Abouyannis M, James C, Roberts L. Attitudes of serodiscordant couples towards antiretroviral-based HIV prevention strategies in Kenya: a qualitative study. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2015;29(1):33–42.

Galea JT, Kinsler JJ, Salazar X, et al. Acceptability of pre-exposure prophylaxis as an HIV prevention strategy: barriers and facilitators to pre-exposure prophylaxis uptake among at-risk Peruvian populations. Int J STD AIDS. 2011;22(5):256–62.

Galindo GR, Walker JJ, Hazelton P, et al. Community member perspectives from transgender women and men who have sex with men on pre-exposure prophylaxis as an HIV prevention strategy: implications for implementation. Implement Sci. 2012;7:116.

Gilleece Y, Whetham J, Charlwood L, McInnes C, Payne E, Taylor S. Pre-exposure prophylaxis exposure for conception as a risk-reduction strategy in HIV-positive men and HIV-negative women in the UK. HIV Med. 2011;12:10.

Golub S, Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Gamarel K, Rendina J, Nanin J, Parsons J. Psychosocial predictors of acceptability and risk compensation for pre-exposure prophylaxis. (PrEP): results from 3 studies of critical populations. J Int Assoc Physician AIDS Care. 2012;11(6):394.

Golub SA. Tensions between the epidemiology and psychology of HIV risk: implications for pre-exposure prophylaxis. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(9):1686–93.

Golub SA, Gamarel KE, Rendina HJ, Surace A, Lelutiu-Weinberger CL. From efficacy to effectiveness: facilitators and barriers to PrEP acceptability and motivations for adherence among MSM and transgender women in New York City. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013;27(4):248–54.

Guest G, Shattuck D, Johnson L, et al. Acceptability of PrEP for HIV prevention among women at high risk for HIV. J Women’s Health. 2010;19(4):791–8.

Heffron R, Ngure K, Mugo N, et al. Willingness of Kenyan HIV-1 serodiscordant couples to use antiretroviral-based HIV-1 prevention strategies. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61(1):116–9.

Idoko J, Folayan MO, Dadem NY, Kolawole GO, Anenih J, Alhassan E. “Why should I take drugs for your infection?”: outcomes of formative research on the use of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in Nigeria. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:349.

Jackson T, Huang A, Chen H, Gao X, Zhang Y, Zhong X. Predictors of willingness to use HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among female sex workers in Southwest China. AIDS Care. 2013;25(5):601–5.

Kandathil S, Champeau D. Women initiated solution to prevent HIV/AIDS (the WISH study): factors associated with intentions to use microbicides and tenofovir. Paper presented at: XIX International AIDS Conference. Washington, 2012 [Abstract WEPE268—Poster Exhibition].

Kapur A, Tang E, Tieu H, Koblin B, Ellman T, Sobieszczyk M. Knowledge, attitudes and willingness of New York City providers to prescribe oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention. Paper presented at: XIX International AIDS Conference. Washington, 2012.

Karris MY, Beekmann SE, Mehta SR, Anderson CM, Polgreen PM. Are we prepped for preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP)? provider opinions on the real-world use of PrEP in the United States and Canada. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;58(5):704–12.

Khawcharoenporn T, Chunloy K, Apisarnthanarak A. HIV knowledge, risk perception and pre-exposure prophylaxis interest among Thai university students. Int J STD AIDS. 2015;26(14):1007–16.

Khawcharoenporn T, Kendrick S, Smith K. HIV risk perception and preexposure prophylaxis interest among a heterosexual population visiting a sexually transmitted infection clinic. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26(4):222–33.

Krakower D, Ware N, Mitty JA, Maloney K, Mayer KH. HIV providers’ perceived barriers and facilitators to implementing pre-exposure prophylaxis in care settings: a qualitative study. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(9):1712–21.

Kruse L, Stover K, Henderson H. Perceptions of emtricitabine-tenofovir in HIV PrEP. HIV Clin. 2014;26(1):1–4.

Kuo I, Gregory Phillips I, Magnus M, et al. Willingness to use pre-exposure prophylaxis among community-recruited injection drug users. Race/Ethnicity. 2014;50(228):82–7.

Kwakwa H. Perceptions of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in a high-risk population in urban United States. Paper presented at: 2014 National STD Prevention Conference, Atlanta, 2014.

Kwakwa H, Wahome R. Perceptions of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in African and caribbean communities in urban United States. Sex Transm Dis. 2014;41:S123–4.

Leonardi M, Lee E, Tan DH. Awareness of, usage of and willingness to use HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among men in downtown Toronto, Canada. Int J STD AIDS. 2011;22(12):738–41.

Liu A, Cohen S, Follansbee S, et al. Early experiences implementing pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention in San Francisco. PLoS Med. 2014;11(3):e1001613.

Mack N, Evens EM, Tolley EE, et al. The importance of choice in the rollout of ARV-based prevention to user groups in Kenya and South Africa: a qualitative study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17(3 Suppl 2):19157.

Mack N, Odhiambo J, Wong CM, Agot K. Barriers and facilitators to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) eligibility screening and ongoing HIV testing among target populations in Bondo and Rarieda, Kenya: results of a consultation with community stakeholders. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):231.

Madenwald T, Fuchs J, Sobieszczyk M, et al. Attitudes and intent to use PrEP among current phase II preventive HIV-1 vaccine trial participants. Paper presented at: AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. New York, 2011.

Magazi B, Stadler J, Delany-Moretlwe S, et al. Influences on visit retention in clinical trials: insights from qualitative research during the VOICE trial in Johannesburg, South Africa. BMC Women’s Health. 2014;14:88.

Mark D, Amico K, Wallace M, et al. Acceptability of oral intermittent pre-exposure prophylaxis as a biomedical HIV prevention strategyresults from the South African ADAPT (HPTN 067) Preparatory Study. Paper presented at: Journal of the International AIDS Society. Geneva, 2012.

Matthews LT, Heffron R, Mugo NR, et al. High medication adherence during periconception periods among HIV-1-uninfected women participating in a clinical trial of antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;67(1):91–7.

Matyanga CMJ, Khoza S, Gavi S. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis: pharmacists knowledge, perception and willingness to adopt future implementation in a Zimbabwean urban Setting. East and Cent African J Pharm Sci. 2014;17:3–9.

Mbogua J, Ngongo B, Ndegwa J, Bender B, Manguyu F. A survey of community opinions and preferences on PrEP, microbicides and vaccines in 5 regions and with key populations in Kenya. Paper presented at: AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. New York, 2013.

McKenna KJ, Ahmed K, Agot K, Makatu SJ, Odhiambo J, Skhosana J, Stalker M, Corneli A, for the FEM-PrEP Study Group. Risk perception and HIV worry among seroconverters in the FEM-PrEP clinical trial. 7th IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis and Treatment. Kuala Lumpur, 2013 [Abstract no. TUPE3862013].

Mijiti P, Yahepu D, Zhong X, et al. Awareness of and willingness to use oral pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among HIV-serodiscordant heterosexual couples: a cross-sectional survey in Xinjiang, China. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(7):e67392.

Mills LA, Kwaro D, Odongo F, et al. Acceptability of novel ARV-based HIV prevention methods in a rural Kenyan health and demographic surveillance community. Paper presented at: AIDS 2012 Conference Poster. Washington, 2012 [Abstract THPE121].

Minnis AM, Gandham S, Richardson BA, et al. Adherence and acceptability in MTN 001: a randomized cross-over trial of daily oral and topical tenofovir for HIV prevention in women. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(2):737–47.

Montgomery ET, van der Straten A, Stadler J, et al. Male partner influence on women’s HIV prevention trial participation and use of pre-exposure prophylaxis: the importance of “understanding”. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(5):784–93.

Mujugira A, Heffron R, Celum C, Mugo N, Nakku-Joloba E, Baeten JM. Fertility intentions and interest in early antiretroviral therapy among East African HIV-1-infected individuals in serodiscordant partnerships. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63(1):e33–5.

Mullins TL, Lally M, Zimet G, Kahn JA. Clinician attitudes toward CDC interim pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) guidance and operationalizing PrEP for adolescents. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2015;29(4):193–203.

Ngure K, Baeten JM, Mugo N, et al. My intention was a child but I was very afraid: fertility intentions and HIV risk perceptions among HIV-serodiscordant couples experiencing pregnancy in Kenya. AIDS Care. 2014;26(10):1283–7.

Nwagwu G, Georges J, Weathers N. Perceived barriers to adoption of pre-exposure HIB therapy among MfF-TG youths. Commun Nurs Res. 2013;46:471.

Parker K. Evaluation of an individual-level intervention to increase knowledge and the likelihood of use for PrEP: results from a pilot study. Paper presented at: 2014 National STD Prevention Conference. Atlanta, 2014.

Peinado J, Lama JR, Galea JT, et al. Acceptability of oral versus rectal HIV preexposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men and transgender women in Peru. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2013;12(4):278–83.

Peng B, Yang X, Zhang Y, et al. Willingness to use pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among female sex workers: a cross-sectional study in China. HIV/AIDS—Res Palliat Care. 2012;4:149–58.

Prem Kumar SG, Kumar GA, Poluru R, et al. Contact with HIV prevention programmes & willingness for new interventions among truckers in India. Indian J Med Res. 2013;137(6):1061–71.

Puro V, Palummieri A, De Carli G, Piselli P, Ippolito G. Attitude towards antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) prescription among HIV specialists. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13(1):217.

Qiu L, Tian K, Zhong X, et al. Investigation on acceptability of pre-exposure prophylaxis among female sex workers in Sichuan, Xinjiang and Guangxi of China. J Shanghai Jaiotong Univ. 2012;32(4):508–13.

Roberts ST, Haberer J, Celum C, et al. Intimate partner violence and adherence to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in African women in HIV serodiscordant relationships: A prospective cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(3):313–22.

Roberts ST, Heffron R, Ngure K, et al. Preferences for daily or intermittent pre-exposure prophylaxis regimens and ability to anticipate sex among HIV uninfected members of Kenyan HIV serodiscordant couples. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(9):1701–11.

Rosenthal E, Piroth L, Cua E, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) of HIV infection in France: a nationwide cross-sectional study (PREVIC study). AIDS Care. 2014;26(2):176–85.

Rubtsova A, Wingood G, Dunkle K, Camp C, DiClemente R. Young adult women and correlates of potential adoption of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): results of a national survey. Curr HIV Res. 2014;11(7):543–8.

Scherer ML, Douglas NC, Churnet BH, et al. Survey of HIV care providers on management of HIV serodiscordant couples—assessment of attitudes, knowledge, and practices. AIDS Care. 2014;26(11):1435–9.

Schneider JA, Dandona R, Pasupneti S, et al. Initial commitment to pre-exposure prophylaxis and circumcision for HIV prevention amongst Indian truck drivers. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(7):e11922.

Schneider JA, Kumar R, Dandona R, et al. Social network and risk-taking behavior most associated with rapid HIV testing, circumcision, and preexposure prophylaxis acceptability among high-risk Indian men. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2012;26(10):631–40.

Schwartz SR, Bassett J, Sanne I, Phofa R, Yende N, Van Rie A. Implementation of a safer conception service for HIV-affected couples in South Africa. AIDS. 2014;28(Suppl 3):S277–85.

Senn H, Wilton J, Sharma M, Fowler S, Tan DH. Knowledge of and opinions on HIV preexposure prophylaxis among front-line service providers at Canadian AIDS service organizations. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2013;29(9):1183–9.

Shaeer KM, Sherman EM, Shafiq S, Hardigan P. Exploratory survey of Florida pharmacists’ experience, knowledge, and perception of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. J American Pharm Assoc. 2014;54(6):610–7.

Sharma M, Wilton J, Senn H, Fowler S, Tan DHS. Preparing for PrEP: perceptions and readiness of Canadian physicians for the implementation of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(8):e105283.

Smith DK, Ntekop E, Pals S. Willingness to use, prescribe, or publicly fund PrEP services: results from 3 national surveys in the United States. Paper presented at: AIDS 2010. Vienna, 2010.

Smith DK, Toledo L, Smith DJ, Adams MA, Rothenberg R. Attitudes and program preferences of African-American urban young adults about pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). AIDS Educ Prev. 2012;24(5):408–21.

Socías ME, Sued O, Pryluka D, Fink V, Cesar C, Cahn P. Willingness of Argentinean HIV care providers to adopt PrEP as a risk reduction strategy in different scenarios. 7th IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis and Treatment. Kula Lumpur, 2013 [Abstract no. TUPE418].

Spector AY, Remien RH, Tross S. PrEP in substance abuse treatment: a qualitative study of treatment provider perspectives. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2015;10(1):1.

Stein M, Thurmond P, Bailey G. Willingness to use HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among opiate users. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(9):1694–700.

Tang EC, Sobieszczyk ME, Shu E, Gonzales P, Sanchez J, Lama JR. Provider attitudes toward oral preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among high-risk men who have sex with men in Lima, Peru. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2014;30(5):416–24.

Tangmunkongvorakul A, Chariyalertsak S, Amico KR, et al. Facilitators and barriers to medication adherence in an HIV prevention study among men who have sex with men in the iPrEx study in Chiang Mai, Thailand. AIDS Care. 2013;25(8):961–7.

Tellalian D, Maznavi K, Bredeek UF, Hardy WD. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV infection: results of a survey of HIV healthcare providers evaluating their knowledge, attitudes, and prescribing practices. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2013;27(10):553–9.

Tripathi A, Ogbuanu C, Monger M, Gibson JJ, Duffus WA. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection: healthcare providers’ knowledge, perception, and willingness to adopt future implementation in the southern US. South Med J. 2012;105(4):199–206.

Tripathi A, Whiteside YO, Duffus WA. Perceptions and attitudes about preexposure prophylaxis among seronegative partners and the potential of sexual disinhibition. South Med J. 2013;106(10):558–64.

Van der Elst EM, Mbogua J, Operario D, et al. High acceptability of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis but challenges in adherence and use: qualitative insights from a phase I trial of intermittent and daily PrEP in at-risk populations in Kenya. AIDS Behav. 2012;17(6):2162–72.

van der Straten A, Stadler J, Montgomery E, et al. Women’s experiences with oral and vaginal pre-exposure prophylaxis: the VOICE-C qualitative study in Johannesburg, South Africa. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2):e89118.

Vernazza PL, Graf I, Sonnenberg-Schwan U, Geit M, Meurer A. Preexposure prophylaxis and timed intercourse for HIV-discordant couples willing to conceive a child. AIDS. 2011;25(16):2005–8.

Wagner GJ, Goggin K, Mindry D, et al. Correlates of use of timed unprotected intercourse to reduce horizontal transmission among Ugandan HIV clients with fertility intentions. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(6):1078–88.

Wamuti B, Odoyo J, Rono B, Cohen C, Bukusi E. Comparison of adherence with pre-exposure prophylaxis among HIV-1-negative clinical trial participants in serodiscordant relationships in Kisumu before and after release of the trial results. Paper presented at: 7th IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention. Kuala Lumpur, 2013 [Oral Abstract-WEAC0105].

Ware NC, Wyatt MA, Haberer JE, et al. Whatʼs love got to do with it? explaining adherence to oral antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV-serodiscordant couples. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59(5):463–8.

Weathers N, Nwagwu G. Perceptions of HIV pre-exposure chemoprophylaxis in high-risk men. Commun Nurs Res. 2013;46:268.

Weber S, Waldura J, Cohan D. Safer conception options for HIV serodiscordant couples in the United States: experience of the National Perinatal HIV Hotline and Clinicians’ Network. Paper presented at: Journal of the International AIDS Society. Mexico, 2012.

Wheelock A, Eisingerich AB, Ananworanich J, et al. Are Thai MSM willing to take PrEP for HIV prevention? An analysis of attitudes, preferences and acceptance. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e54288.

Wheelock A, Eisingerich AB, Gomez GB, Gray E, Dybul MR, Piot P. Views of policymakers, healthcare workers and NGOs on HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): a multinational qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2012;2(4):e001234.

Whetham J, Taylor S, Charlwood L, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis for conception (PrEP-C) as a risk reduction strategy in HIV-positive men and HIV-negative women in the UK. AIDS Care. 2014;26(3):332–6.

White JM, Mimiaga MJ, Krakower DS, Mayer KH. Evolution of Massachusetts physician attitudes, knowledge, and experience regarding the use of antiretrovirals for HIV prevention. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26(7):395–405.

Whiteside YO, Harris T, Scanlon C, Clarkson S, Duffus W. Self-perceived risk of HIV infection and attitudes about preexposure prophylaxis among sexually transmitted disease clinic attendees in South Carolina. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2011;25(6):365–70.

Wingood GM, Dunkle K, Camp C, et al. Racial differences and correlates of potential adoption of preexposure prophylaxis: results of a national survey. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63(Suppl 1):S95–101.

Wong C, Parker C, Ahmed K, et al. Participant motivation for enrolling and continuing in the FEM-PrEP HIV prevention clinical trial. Paper presented at: International AIDS Society (IAS) 7th Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention. Kuala Lumpur, 2013.

Yang D, Chariyalertsak C, Wongthanee A, et al. Acceptability of pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men and transgender women in northern Thailand. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):e76650.

Ye L, Wei S, Zou Y, et al. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis interest among female sex workers in Guangxi, China. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(1):e86200.

Young I, Flowers P, McDaid LM. Barriers to uptake and use of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among communities most affected by HIV in the UK: findings from a qualitative study in Scotland. BMJ Open. 2014;4(11):e005717.

Zhao Z, Sun Y, Xue Q, et al. [Acceptability of pre-exposure prophylaxis among female sex workers in Xinjiang]. Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban [J Zhejiang Univ, Med Sci]. 2011;40(3):281–5.

Zhong X, Zhong XN, Peng B, et al. Attitude on pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among drug users from high-risk population of aids in western China. Acad J Second Military Med Univ. 2012;33(4):374–9.

Carlo Hojilla J, Koester KA, Cohen SE, et al. Sexual behavior, risk compensation, and HIV prevention strategies among participants in the San Francisco PrEP demonstration project: a qualitative analysis of counseling notes. AIDS Behav. 2015;20(7):1461–9.

Koester KA, Amico KR, Liu A, et al. Sex on PrEP: qualitative findings from the iPrEx open label extension (OLE) in the US. Paper presented at: 20th International AIDS Conference. Melbourne, 2014 [Abstract no. TUAC0102].

UNAIDS, WHO, Wits. Sex workers’ hopes and fears for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis: Recommendations from a discussion meeting 2013.

NSWP. Global consultation: PrEP and early treatment as HIV prevention strategies: Sex workers community experiences and perspectives. 2014.

INPUD and UNAIDS consultation on PrEP with people who inject drugs: Meeting report. Chisinau, 2014.

Henderson M. Values and preferences of people who inject drugs, and views of experts, activists and service providers: HIV prevention, harm reduction and related issues. 2014.

Acknowledgements

We thank Salim Abdool Karim, Waffa El-Sadr, and the entire WHO Technical Working Group on PrEP for their guidance and input. We also thank Sophie Morse, Jen Robinson, and Ping Teresa Yeh for their help with coding and reference management. This review was commissioned by WHO in accordance with the GRADE process used for guideline development, which requires assessment and consideration of values and preferences of users. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation provided funds to WHO to carry out this work but was not involved in any part of the review process. The corresponding author had full access to all data presented in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Author Contributions

CK, KO, RB and FK conceived the review, including developing the research question, outcomes of interest, and inclusion criteria. VF, SD, CK, and FK, conducted the literature search and screening. CK designed the protocol and conducted several previous reviews on PrEP effectiveness in sub-populations with VF. FK conducted the data abstraction and data analysis. CK and KR provided feedback on the analysis. FK wrote the first draft of this manuscript. All authors provided feedback on drafts of the manuscript and approved of the final version.

Funding

This review was funded through WHO/BMGF.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Participants

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the authors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Koechlin, F.M., Fonner, V.A., Dalglish, S.L. et al. Values and Preferences on the Use of Oral Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV Prevention Among Multiple Populations: A Systematic Review of the Literature. AIDS Behav 21, 1325–1335 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1627-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1627-z