Abstract

The use of unsupervised self-testing as part of a national screening program for HIV infection in resource-poor environments with high HIV prevalence may have a number of attractive aspects, such as increasing access to services for hard to reach and isolated populations. However, the presence of such technologies is at a relatively early stage in terms of use and impact in the field. In this paper, a principle-based approach, that recognizes the fundamentally utilitarian nature of public health combined with a focus on autonomy, is used as a lens to explore some of the ethical issues raised by HIV self-testing. The conclusion reached in this review is that at this point in time, on the basis of the principles of utility and respect for autonomy, it is not ethically appropriate to incorporate unsupervised HIV self-testing as part of a public health screening program in resource-poor environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

This paper considers unsupervised self-testing for HIV (HIVST), as part of a national screening program, in resource-poor environments. Further, it explores how an adequate conception of autonomy might impact an ethical analysis of HIVST in such environments. HIVST in this context refers to the use of HIVST kits, such as the OraQuick® In-Home HIV Test, which was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2012 [1]. Such HIVST kits are available for purchase or distributed free of charge by public health authorities in many settings. HIVST can enable individuals to test for HIV in the privacy of their own home or other similar settings. Both supervised and unsupervised self-testing strategies have been identified in the literature [2]. The ethical concerns this paper raises center on unsupervised HIVST; whereby there is neither a direct link to pre- or post-test counseling, nor to prevention, care and treatment services.

The increased availability of anti-retroviral therapy (ART) has, in recent years, led to a massive scale-up of screening for HIV infection internationally. The question for many governments is not whether there should be a scale-up of testing for HIV, but how to do so in the most effective, efficient and equitable manner possible [3].

In countries with a high prevalence of HIV, where sophisticated medical laboratories are few, and where it is very difficult to access remote populations, governments and public health policy makers are turning to HIVST as a means of vastly increasing the reach of screening programs [4, 5]. HIVST devices can be portable, easy to use and provide rapid test results [6]. Due to improvements in relevant technology, HIVST has also become more accurate. Evidence suggests that HIVST is more attractive than traditional screening methods to certain groups [2]. Further, HIVST is also likely to help in reaching both remote and hard to access groups such as sex workers and men who have sex with men (MSM) [6, 7].

Given the imperative to scale-up HIV screening and the impact of ART in both reducing viral load and making persons living with HIV less infective [8], it is reasonable to argue for the inclusion of all accurate approaches to HIV testing in public health screening programs. In addition, convenience and acceptability [2] underline the benefit of HIVST as an important strategy in such screening programs, particularly in resource-poor environments, such as sub-Saharan Africa.

Millions of people are currently infected with HIV. A significant percentage of who are unaware of their HIV serostatus [9]. These facts, combined with an increased availability and effectiveness of ART [8], make scaling-up HIV screening imperative. A combination of factors has led a number of governments and policy makers in resource-poor environments to look to the use of HIVST as part of HIV screening programs. However, given the profile of the populations living with HIV, and the context in which they live, unsupervised HIVST is arguably unethical from the perspective of both principles of utility and respect for autonomy.

The principle of utility, the core principle of utilitarianism, requires that in any situation of moral decision making, moral actors should strive to do that which will increase the good (defined variously as happiness, benefit and so forth) over the bad (pain, burden). In decision making in the public moral sphere, for example in issues of resource allocation, it is frequently suggested that the principle of utility is a very attractive, if not the only viable moral principle from which to operate [10]. The principle of autonomy, on the other hand, focuses on the individual and the individual’s right to self-determining choices and decisions. This principle has gained increasing importance in the sphere of personal medicine during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Some medical ethicists argue that autonomy is the primary principle of biomedical ethics [11, 12].

In terms of the use of well-established self-testing devices such as pregnancy, cholesterol and prostatic antigen (PSA) tests for example, the demand and indeed the justification for the development and use of such tests is intimately linked with the notion of personal autonomy and the individual’s right to information regarding health decisions as well as his or her right to participate in decisions affecting his or her health and life-style [13, 14]. Self-testing also fits well within current policy and rhetoric regarding individual responsibility for one’s health and the onus on individuals to participate in their health care and in health service delivery [14, 15].

Experiences to date with self-testing have raised concerns in a number of areas including the following: (a) inaccurate claims with regards to the efficacy of PSA to improve outcomes for prostatic disease [16], (b) the promotion of a culture of the “worried well” [17], (c) contribution to psychological distress due to false positives [18], and (d) the “creation” of a perceived need for HIVST only for commercial reasons [19].

Such concerns should be borne in mind when considering the ethics of HIVST in resource-poor environments, where regulation and oversight may be even more difficult to achieve than in the context of Western, personalized health care where self-testing generally has its developmental roots.

Ethics and HIVST: Issues of Population Profile

There are numerous issues regarding the profile and context of those living with HIV that are relevant to an analysis of how best to scale-up HIV screening (and subsequent linkage to care and treatment services) in an ethical manner.

Approximately 25 million people in sub-Saharan Africa are currently living with HIV. There are a number of key populations and groups that are at high risk for HIV, such as sex workers, people who inject drugs, transgender people and MSM. In many resource-poor countries women and girls are also at a particularly high risk of infection. Females account for 57 % of all those infected in sub-Saharan Africa [9]. As far back as 2001 Van Niekerk commented: “The situation in Africa has shown definitively that AIDS flourishes most demonstrably in a society where women are particularly vulnerable” [20].

Many people who are living with HIV are unaware of their serostatus [9]. Identifying and diagnosing people living with HIV and linking them with support and treatment is crucial to these individuals’ survival, and to the survival of their sexual partners.

Resource-poor environments can impact the life expectancy, living conditions, nutritional status, disease patterns, choices, security and life trajectory of the poor living in these settings. Additionally, resource-poor environments may be unable to fully protect the human rights of its citizens [21]. Thus engaging with people living with HIV in resource-poor environments is fundamentally important, as the options available may be particularly limited.

The role and status of women, as an example, in many environments and societies, often means women’s dignity as human beings is constantly in danger of being undermined or denied. In some settings, women may be directly discriminated against in national legislation, and, perhaps more commonly in the societal norms [22, 23]. Women are often directly and indirectly discriminated against in tradition, cultural and social practices and norms [24–26]. In such societies or groups, females may be considered the property either of their parents, or their spouse. Further, women have less access to education [9, 25] and thus are more likely to be dependent on males for financial security [25–27]. This results in freedom of choice, movement and the ability to exercise autonomy, as understood in twenty-first century Western societies and health care systems, being severely curtailed.

The need to reform the role and status of women is well recognized in many settings, for example, countries such as South Africa have brought in legislation to assist such reform [28]. However, when power relations among those involved in the debate (such as gender relations and the role status of women in society) are both the context and the subject matter, open discussion is likely to be severely hampered and actual reform is, at best, very slow in coming [24].

Thus in the context of HIV infection in many resource-poor environments, women and girls, like sex workers, MSM and domestic workers, are particularly vulnerable. Due to their social status and lack of legal protection, such vulnerable populations may be subjected to mistreatment and coercion. Women, for example, are more vulnerable to violence, abandonment, destitution or death at the hands of their partners, families or communities [24, 26, 29, 30]. There is also evidence that women living with HIV can suffer greater violence post-diagnosis than men [31].

Ethics and HIVST: Issues of Utility

Availability and inclusion of unsupervised HIVST as part of public health programs, in such contexts, may increase these vulnerabilities and expose individuals to coercive testing. Vulnerabilities may be increased due to physical, psychological and social power imbalance and lack of personal control over access to one’s body; by virtue of disempowerment, dependency and lack of or inability to enforce structures, policy and processes protective of human rights. Increased vulnerability leads to increased burden in the lives of these individuals.

Incorporating HIVST as part of a public health screening program, from the perspective of the principle of utility—the fundamental principle of public health ethics [32]—appears to be reasonable. If HIVST, as a screening approach, is likely to reach more people, specifically people living in remote areas or difficult to access groups, such as men, sex workers and MSM, then the potential benefits may outweigh potential risks. Also, HIVST offers increased convenience, and the ability for individuals to potentially forgo unnecessary or ineffective counseling, thus further reducing the individual-level burdens to access HIV testing services.

However if in reaching these populations, or individuals who wish to avoid education or counseling, some individuals are in danger of being coerced into accepting testing, or are tested without being linked into care and treatment, or are vulnerable to abuse, violence, abandonment or destitution, then the balance of benefit over burden can swing in a negative direction.

On the utilitarian calculus, at a basic level, each individual counts as one and only one. For example, men are less likely to access HIV testing services and reportedly prefer self-testing to provider initiated testing and counseling (PITC) [2], but only 43 % of all people living with HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa are male. All other things being equal, HIVST should be encouraged in order to (a) encourage more men to be tested and (b) enable more men to become aware of their HIV status as a first step to accessing treatment and care. However all other things are not equal, certain groups may be at increased risk of coercion and violence or other forms of abuse if HIVST is introduced as part of a public health screening program. Some of those at increased risk of coercion, violence and abuse are women. Some of them are sex workers, many but not all of whom are women, some are MSM, some are migrant and domestic workers, who may also be men. Thus the individuals at risk are both men and women—this reduces the overall number of men in the population who may benefit from the introduction of HIVST as part of a public health initiative.

As suggested above screening is not a neutral activity [33]. It has potentially life-changing (and life-endangering) consequences for the individual screened and many in their intimate circle. It behooves health workers, policy makers and governments engaged in encouraging and implementing HIV screening programs to bear the potential consequences in mind. A relevant issue here is ‘Does the harm of a life threatening infection override these consequences, and who decides?’ If HIVST opens the door to readily available treatment and care then it seems that benefit prevails. However if treatment is unavailable to even some, this deficit, when combined with the potential risks of breaches of the autonomy of the person (including privacy, consent and confidentiality), violence, abandonment and destitution, may result in an outweighing of the possible benefits of HIVST [2, 34].

Thus a relevant question is ‘Does the benefit to burden calculation suggest significant risk of increased burden to vulnerable individuals?’ Given that we know that more women and girls are living with HIV, for example, and given that they are particularly vulnerable in resource-poor environments where social norms and legislative structure do not, or cannot, offer adequate protection of basic rights, HIVST does appear to increase potential risks. An acknowledgement of the risks of testing for HIV could be argued to underlie the omission to collect test results by some pregnant women, who are routinely tested for HIV in antenatal clinics and their reluctance to disclose positive results to their partners [30].It is the case, due to routine testing of pregnant women, that more women have access to HIV testing (and to treatment) than other vulnerable groups; such as migrant and domestic workers and MSM. However some of the risks of screening for HIV may be very similar for these groups.

In order to justify HIVST in resource-poor settings it is necessary to show that despite increased vulnerability there is also a substantial increase in the benefits. If there is clear evidence of a coherent and viable plan to link those who self-test positive, including members of groups exposed to increased vulnerability, to care and treatment then on utilitarian grounds it would still be reasonable and justifiable to argue for the inclusion of unsupervised HIVST as part of a public health screening program. However at this point in time there does not seem to be evidence of either a coherent or a viable linkage program, nor a focused discussion with regards to whose responsibility it is to ensure that people who have a positive self-test result are linked to confirmatory testing, and subsequent care and treatment, if and when needed. If this is an accurate description of the current state of planning with regards linkage of infected individuals to care and treatment, it is then unethical to potentially increase the burden of vulnerability, by integrating unsupervised HIVST as part of public health screening, especially among populations who are already exposed to the burdens of poverty, gender, power deficits and HIV infection, in resource poor environments Thus, despite the many potential benefits of HIVST, on utilitarian grounds an argument can be made against the ethical appropriateness of rolling out unsupervised HIVST as part of a public health screening program. This is particularly the case when there is evidence of effective home based HIV testing initiatives, which provide many of the same benefits of HIVST by increasing access to remote populations, couples testing and also provides a clear pathway for clients to link to care and treatment [2, 35–37].

Recognizing the reasonable concern of potential coercive testing and the possible aftermath of a positive self-test result is important in understanding the ethical implications of HIVST. If it could be determined that an individual who has a positive self-test result is responsible for seeking confirmatory testing and, if needed, could access treatment with ease, then the potential benefit of HIVST increases. Evidence suggests this is often the case, as many groups, including men, MSM, and couples, report that they prefer the convenience and privacy offered by HIVST to other HIV testing approached [2, 37]. However these same groups also report that there is still a need for counseling and information following HIVST [36]. Therefore, the context in which HIVST is introduced and how it is implemented is an important factor to consider when determining the ethical acceptability of integrating HIVST as part of a public health screening program. It should also be noted, however, that ethical concerns regarding the integration of HIVST as part of public health measures does not automatically rule out HIVST in the context of personal health care. This will be discussed further below.

Respect for Autonomy

However a further argument against unsupervised HIVST comes from considerations of the principle of respect of autonomy, particularly when using a conceptualization of autonomy in terms of relational autonomy is used [38–40].

Autonomy is generally defined as a multi-faceted concept including the ability to make decisions for one’s self, to exercise choice, to deliberate over options, to self-determine and to self-govern. The concept has evolved from its Greek origins via influences from Immanuel Kant and John Stuart Mill, with respective emphasis on deliberative self-regulation and the ability to follow one’s preferences, to current libertarian conceptions of autonomy. Libertarian conceptions of autonomy, as freedom from constraint and freedom to choose, are growing in Western society and are linked, within the context of health care, with consumerist free-choice [41].

However there is a growing critique of this conception of autonomy and its application within health care [7, 14, 42, 43]. A richer understanding of autonomy recognizes that human beings do not exist or flourish in isolation. An integral part of being human is being intimately connected to other people. It would therefore seem that in respecting our ability and right to exercise our autonomy, the socially embedded nature of our being should form part of any adequate notion of autonomy. Conceptualizations of autonomy may not be divorced from the cultural context in which, for example, issues of HIV screening (including the process of HIVST) arise. The cultural context sets the scene for a more relational perspective highlighting, for example, the societal implications of screening. Thus, while recognizing that the right to give informed consent is an important practical application of autonomy, so also is the recognition that in certain circumstances such as illness, serious stress, poverty and relative powerlessness, the exercise of one’s autonomy depends not only on the negative rights to non-interference but on the right to adequate support, assistance and protection. In this vein, it can be argued that the principles of respect for autonomy and justice are connected [43].

In most theories of autonomy two basic requirements must be fulfilled for autonomy to exist:

-

1.

Liberty (freedom from controlling or coercive influences) and

-

2.

Agency (capacity for intentional action) [10].

Respecting autonomy requires not only an attitude of respect for the individuals involved, it requires the taking of ‘respectful action’. It is more than non-interference; it may require developing and supporting the other’s capacity for autonomous choice by removing fears and conditions that undermine autonomous action. It requires us not only to not use others as means to our own ends, but to assist them in achieving their ends [10].

Within the context of HIVST in resource-poor environments two potential autonomy-related issues that may emerge are issues related to informed consent and fears of violence and criminalization following a positive result. With regards to informed consent the World Health Organization (WHO) HIV testing and counseling (HTC) guidelines indicate that mandatory testing is never warranted and that service must adhere to the 5Cs: consent, confidentiality, counselling, correct test results and connection/linkage to prevention, care and treatment. Thus, individuals who test for HIV must be informed of the process of HTC, about available follow-up services and of the right to refuse testing [44]. In the context of unsupervised HIVST the possibilities of ensuring that information about testing and available follow-up services is provided consistently, need to be examined.

Should such information and service provision be consistently available concerns regarding the ethical implications of unsupervised HIVST will likely diminish. The image of an individual collecting and administering a rapid HIV self-test in private, at a conducive time, to check his or her status rather that travelling to the nearest health facility for such testing, sometimes a considerable cost and inconvenience, appears to be reasonable. However, the image of the same individual collecting four such kits, taking them home and requiring a partner and two domestic workers to take the test with them, without any requirement to provide information or follow-up services, conjures up a different picture and set of concerns.

From the perspective of the relational reality of human life, basic human sympathy and moral behavior, it would seem incumbent that people living with HIV disclose their serostatus to their sexual partners. The implication for partners (and their children) in this scenario is, without question, potentially life threatening. However there are risks for the partner who discloses their HIV serostatus, such as potential stigma, abuse, violence or prosecution. Such risks go against supporting our relational existence and immediate-term concerns, of self-protection and survival, may override the moral imperative to disclose. It is also possible that an individual who self-tests for HIV may avoid confirmatory testing and not receive a HIV diagnosis. Self-testers that delay confirmatory testing may do so to reduce feelings of guilt or responsibility.

A conceptualization of autonomy, from the liberty element to the idea that, in certain circumstances, we are morally obliged to help people achieve their ends, is important in considering the ethical acceptability of the inclusion of unsupervised HIVST in public health screening programs. It seems that this is where there is a difference in enabling individual choice through access to HIVST by approving certain devices for individual use at personal cost—such as the current case with pregnancy and cholesterol test kits—and integrating HIVST as part of a public health screening program. If accurate HIVST kits are available, and their sale and use of quality products can be assured, arguments supporting individual autonomous choice suggest that access to HIVST kits should be facilitated, not prevented. This, broadly, is the argument developed by Allais et al. in the current issue.

However the integration of HIVST as part of a public health program puts greater onus on policy makers and practitioners to ensure public benefit from such a move. Such benefit should, as argued above, at worst neutralize any increased burden and at best increase overall public benefit of HIVST. Firstly there is the question regarding the existence of individual liberty as well as liberty rights for members of the vulnerable groups of concern in this paper—sex workers, many women in resource-poor environments, migrant and domestic workers in such environments. The restrictions on or basic lack of liberty of persons in such situations has significant implications for the ability of these individuals to exercise autonomy, autonomous choice, and the ability to autonomously refuse HIVST. Secondly, on the basis of the liberty issue (or absence thereof) it is possible to argue that if HIVST is introduced as a public health screening program liberty and autonomous decision making must be assured. This is a difficult proposition, though supervised HIVST appears to hold promise [35–37]. If HIVST is introduced without such assurance and in such contexts, it is ignoring the rights and dignity, and autonomy capacities of the individual members of the vulnerable groups of concern. One is thus directly infringing on the principle of respect for autonomy and using these vulnerable individuals as means to others’ ends.

Conclusion

The urgency to scale up diagnosis and treatment of HIV infection is clear. Effective home based testing and counseling for HIV is possible, as is supervised HIVST [2, 35–37]. Both of these testing strategies appear to offer efficient and effective ways to make screening for HIV highly acceptable and convenient and linkage to care and treatment possible. However, there is little evidence to date that this is the case for unsupervised HIVST [2]. The particular focus of this paper is on the ethical appropriateness of the introduction of unsupervised HIVST in the context of resource-poor environments, where women and girls, migrant workers, domestic workers, sex workers and MSM may be particularly vulnerable. These vulnerable groups are a significant part of the target populations where HIVST is being considered for public health screening purposes. On utilitarian grounds evidence must demonstrate that unsupervised HIVST in resource-poor settings will increase the benefit over burden to these vulnerable populations. On autonomy grounds there must also be assurance that both the liberty and agency of the vulnerable individuals of concern are adequately protected in unsupervised HIV programs as part of a public health initiative. Then and only then should unsupervised HIVST become part of public health screening.

References

United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA). First rapid home-use HIV kit approved; 2012 [cited 2013 Mar 8]. http://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm310545.htm.

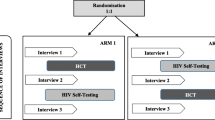

Pant Pai N, Sharma J, Shivkumar S, et al. Supervised and unsupervised self-testing for HIV in high- and low-risk populations: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2013;10(4):1001414. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.11001414.

Obermeyer CM, Bott S, Bayer R, et al. HIV testing and care in Burkina Faso, Kenya, Malawi and Uganda: ethics on the ground. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2013;13:6.

National AIDS and STI Control Programme (NASCOP), Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation, Kenya. Guidelines for HIV testing and counselling in Kenya. Nairobi: NASCOP; 2008 [cited 2013 Nov 29]. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---ilo_aids/documents/legaldocument/wcms_127533.pdf.

Richer ML, Venter WDF, Gray A. Enabling HIV self-testing in South Africa. S Afr J HIV Med. 2013 [cited 2013 Nov 29]; 13(4). http://www.sajhivmed.org.za/index.php/sajhivmed/article/view/858/762.

Meyers JE, El-Sadr WM, Zerbe A, Branson BM. Rapid HIV self-testing: long in coming but opportunities beckon. AIDS. 2013;27(11):1687–91.

Kearns AJ, O’Mathuna DP, Scott PA. Diagnostic self-testing: autonomous choices and relational responsibilities. Bioethics. 2009;24(4):199–207.

Dieffenbach CW, Fauci AS. Thirty years of HIV and AIDS: future challenges and opportunities. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(11):766–71.

Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2013. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2013 [cited 2014 May 27]. http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2013/gr2013/UNAIDS_Global_Report_2013_en.pdf.

Beauchamp T, Childress J. Principles of biomedical ethics. 7th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2013.

Gillon R. Ethics needs principles—four can encompass the rest—and respect for autonomy should be “first among equals”. J Med Ethics. 2003;29:307–12.

Schwartz L, Preece PE, Hendry RA. Medical ethics: a case-based approach. Edinburgh: Saunders; 2002.

Better 2 Know. Prostate health. Better 2 know online; 2014 [cited 2014 Apr 24]. http://www.better2know.ie/home-testing-kits/prostate-health.

Greaney AM, O’Mathuna DP, Scott PA. Patient autonomy and choice in healthcare: self-testing devices as a case in point. Med Health Care and Philos. 2012;15:383–95.

Ryan A, Ives J, Wilson S, Greenfield S. Why members of the public self-test, an interview study. FamPract. 2010;27:570–81.

Ilic D, O’Connor S, Green S, Wilt T. Screening for prostate cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;19(3):CD004720.

Walensky RP, Paltiel AD. Rapid HIV testing at home: does it solve a problem or create one? Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(6):459–62.

Modra L. Prenatal genetic testing kits sold at your local pharmacy: promoting autonomy or promoting confusion? Bioethics. 2006;20(5):254–63.

Whellams M. The approval of over the counter HIV tests: playing fair when making the rules. J Bus Ethics. 2008;77:5–15.

van Niekerk AA. Moral and social complexities of AIDS in Africa. J Med Philos. 2001;27(2):143–62.

United Nations. Universal Declaration on Human Rights. New York: United Nations; 1948 [cited 2014Jun 1]. http://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/index.shtml.

Nussbaum MC. Sex and social justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999.

McCaffery E. Taxing women. Chicago: Chicago University Press; 1997.

Enslin P. Multicultural education, gender and social justice: liberal feminist misgivings. Int J Educ Res. 2001;35:281–92.

World Health Organization (WHO).Integrating gender into HIV/AIDS programs in the health sector: tool to improve responsiveness to women’s needs. Geneva: WHO; 2009[cited 2014Jun 1]. http://www.who.int/gender/documents/hiv/9789241597197/en/.

World Health Organization (WHO). Child marriage: 39,000 every day. Geneva: WHO; 2013 [cited 2013 Mar 3]. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2013/child_marriage_20130307/en/index/html.

Fageeh WMK. Factors associated with domestic violence: a cross sectional survey among women in Jeddah Saudi Arabia. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004242. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004242.

Rautenbach C. Gender, equality, constitutional values and religious family laws in South Africa. Int J Discrimin Law. 2001;5(2–3):103–17.

Mulligan S. Confronting the challenge: poverty, gender and HIV in South Africa. Bern: Peter Lang; 2010.

Hardon A, Vernooij E, Bongololo—Mbera G, et al. Women’s views on consent, counselling and confidentiality in PMTCT: a mixed-methods study in four African countries. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):26.

Osinde MO, et al. Intimate partner violence among women with HIVinfection in rural Uganda: critical implications for policy and practice. BMC Women’s Health. 2011;11:50.

Holland S. Public health ethics. Cambridge: Polity Press; 2007.

Palmer VJ, Yelland JS, Taft AJ. Ethical complexities of screening for depression and intimate partner violence (IPV) in intervention studies. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(Suppl 5):S3.

Faden R, Power M. Social Justice: the moral foundations of public health. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006.

Doherty T, Tabana H, Jackson D, et al. Effect of home based HIV counselling and testing intervention in rural South Africa: cluster randomized trial. BMJ. 2013;346:f3481. doi:10.1136/bmj.f3481.

Choko AT, Desmond N, Webb El, et al. The uptake and accuracy of oral kits for HIV self-testing in high prevalence settings: a cross-sectional feasibility study in Blantyre, Malawi. PLoS Med. 2011;8(10):e1001102.

MacPherson P. Increasing access to HIV testing: self-testing and community testing approaches. IAPAC/BHIVA Conference: Controlling the HIV Epidemic with Antiretrovirals. London. 2013 [cited 2014 Apr 27]. http://www.iapac.org/tasp_prep/presentations/TPSlon13_Panel8_MacPherson.pdf.

Donchin A. Understanding autonomy relationally: towards a reconfiguration of bioethical principles. J Med Philos. 2001;26(4):365–86.

Stoljar N. Informed consent and relational conceptions of autonomy. J Med Philos. 2011;36:375–84.

Agich GJ. Why I wrote… dependence and autonomy in old age. Clin Ethics. 2010;5(2):108–10.

Moreno JD. The triumph of autonomy in bioethics and commercialization in American health care. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2007;16:415–9.

Baylis F, Kenny NP, Sherwin S. A relational account of public health ethics. Public Health Ethics. 2008;1(3):196–209.

Childress J, Faden R, Gaare R, et al. Public Health ethics: mapping the terrain. J Law Med Ethics. 2002;30(2):170–8.

World Health Organization (WHO). Statement on HIV testing and counselling: WHO, UNAIDS reaffirm opposition to mandatory HIV testing. Geneva: WHO; 2012 Nov 28 [cited 2014 Apr 25]. http://www.who.int/hiv/events/2012/world_aids_day/hiv_testing_counselling/en/.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Scott, P.A. Unsupervised Self-testing as Part Public Health Screening for HIV in Resource-Poor Environments: Some Ethical Considerations. AIDS Behav 18 (Suppl 4), 438–444 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0833-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0833-9