Abstract

Food quality is an important issue on the global agenda, particularly in high- and middle-income economies, but of little concern in designing Mexico’s food policy. Food policy has focused on quantity and in the case of maize, on satisfying domestic demand by supporting large commercial agriculture and importing from abroad. However, and as argued in this paper, obtaining a food staple (maize-tortilla) of quality is also an important issue for rural households and contributes to motivating continued smallholder production. Based on case studies in the rural district of Atlacomulco, in the state of Mexico, as well as in two regions of the state of Chiapas, this paper analyzes the production and consumption strategies of rural households. We focus on goals of food security and quality and note differential trends among households of varying characteristics and local contexts. We find that the motivation of small-scale producers to grow maize should be supported by Mexico’s food policy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Data provided by Hugo Perales from Programa de Apoyos Directos al Campo (PROCAMPO) based on maize producers, 2009.

From the mid-1960s, maize and other basic staples were subsidized by guaranteed prices (minimum) controlled by the state agency Compañía Nacional de Subsistencias Populares (CONASUPO). Prices tended to be above world prices (Appendini 2001). CONASUPO closed in 1999.

See SAGARPA-SIAP (2015). Increase in demand is due to population growth, as well as demand for animal feed and industrial use.

Mexico controls aftlatoxins, produced by a fungus present in aftlatoxins B1 (over 20 μg/kg is not allowed for human consumption) (Secretaría de Salud 2002). In contrast, import of transgenic maize is allowed, though forbidden to be sown in Mexico, except in experimental fields.

The program provides technical assistance, infrastructure, and equipment to farmers with less than 5 ha of land. In 2007 it covered 1.6 million hectares and 122.2 thousand maize and bean producers, but dwindled in 2012 to 330.9 thousand ha and 54 thousand producers (SAGARPA and FIRCO 2012).

MasAgro has a budget of 138 million USD over the course of 10 years. In 2012 the assigned budget was 20.3 million USD (SAGARPA and CIMMYT 2012); about 38 % of the average annual PROMAF budget in 2011 (SAGARPA and FIRCO 2012). These budgets represent only a third of the subsidies supporting the commercialization of maize by the government agency Apoyos y Servicios a la Comercialización Agropecuaria (ASERCA) in 2012 of which 80 % went to entrepreneurial farmers and market agents in Sinaloa (own estimates based on ASERCA) (SAGARPA and ASERCA 2013).

There have been several civil society initiatives to promote the consumption of quality tortillas. See for example, the “Sin maíz no hay país” movement (Without maize there is no country), the tortilla shops established by Asociación Nacional de Empresas Campesinas (ANEC), and the Coyote Rojo initiative in the Meseta Purépecha, Michoacan (Baker 2013; Fitting 2011; McNair 2012).

Macro level: Appendini (2001); Barkin (2002); Fitting (2011); Hewitt de Alcántara (1994); Puyana and Romero (2005); Rello and Saavedra (2010); Rubio (2013). At the household level: Appendini et al. (2003); Appendini et al. (2008); Bellon and Hellin (2011); Eakin et al. (2014b); Fitting (2011); de Janvry et al. (1997), de Janvry et al. (1995); Lerner and Appendini (2011); Yunez et al. (2000).

Econometric analysis applied to rural households in Mexico has also shown that small-scale farmers may respond in complex ways to changing market prices for maize, reflecting shadow prices that may differ substantially from market prices—an obvious reason for the persistence of maize in spite of falling prices from the 1990s to 2007 (Arslan and Taylor 2009; Dyer et al. 2006).

See Isakson (2011) for Guatemala.

Ejidos are landholdings distributed during the process of Agrarian Reform (1917–1992) organized in communities in which there are individual plots, common lands, and an urban area.

Nixtamal is the process by which the tortilla masa or dough is made. See footnote 17.

In 2000 the percentage was 35.1, a small decrease of workers in maize and bean agriculture (Contreras Molotla 2014 based on estimates data from the 2000 and 2010 population census). Rural refers to localities of 2500 inhabitants and less.

Maseca (part of Gruma corporation) controls 71.2 % of the maize flour market in Mexico, followed by Minsa (23.5 %). Four other firms account for the rest (Secretaria de Economía 2012).

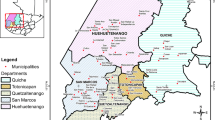

In the Atlacomulco region, 402 households were surveyed in five ejidos located in the municipalities of San Felipe del Progreso, Atlacomulco, Jocotitlán, and Ixtlahuaca. In Chiapas 605 questionnaires were administered to households in the regions of San Cristóbal de las Casas, Comitán and Villaflores. Ejidos were randomly selected from the 2007 ejido PROCAMPO database, and households were also randomly selected within communities. We will refer to the regions as Atlacomulco, Chiapas Highlands, Chiapas Mid and Lowlands. The purpose of the survey was to provide a database for the general project. For other publications, see Eakin et al. (2014b), (2015).

See Malassis, cited by Fonte 2002.

This is the method of making a traditional tortilla: First the grain is cooked with limestone, then ground and made into a masa (dough). Tortillas and other foods (tamales, atoles, pozol, etc.) are made from the masa. A small ball is formed and patted into a flat tortilla with a round metal press (traditionally it was done by hand) and baked on the comal (a flat clay or metal plate). Traditionally this is done over a pit with firewood, which continues to be preferred over a gas stove. Different social actors have different discourses. For example the maize flour/tortilla industry stresses the hygienic and nutritional, technical advantages of consuming industrialized maize flour and tortillas (Appendini 2012). The diversity of regional foods in Mexico also affects preferences and considerations of quality for tortillas and other maize-based foods (sopes, pellizcadas, and so forth).

PROCAMPO (1993 to present) is the most important subsidy for agricultural producers. It is a direct payment to farmers for each hectare registered in the program (up to 100 ha). In 2013 its name was changed to Proagro Productivo, linking the payments to practices enhancing productivity.

The Secretaría de Economía (2012) estimates a conversion rate of 1 kilo maize grain to produce 1.4 kilo of nixtamal masa tortillas. The production of tortillas with maize flour is more efficient than with grain/masa since the conversion rate is 1 kilo of maize to make 1.56 kilos of tortillas. The same source estimates average yearly consumption of tortillas per capita for rural population to be 79.5 kilos of tortillas (56.8 kilo maize for masa tortillas or 1.09 kilos a week, equal to about 4–5 kilos for an average household of four). This is a low consumption estimate compared to our survey results were weekly consumption of grain per household ranges from 13 to 24.6 kilos of maize per week (Table 1). The estimate is also low compared to a yearly per capita consumption of 274 kilos of maize per adult estimated by de Janvry et al. (1995) in the mid-1990s. One reason may be that de Janvry’s and our fieldwork was carried out in maize growing ejidos while the Secretaría de Economía estimate refers to the total rural population in Mexico.

Oportunidades is a poverty alleviation program paid bimonthly to women in order to support health and education. The program was named Progresa when initiated in 2002 and renamed Prospera in 2013.

Lerner and Appendini (2011) found similar patterns in households in the peri-urban area of the city of Toluca (capital of Mexico State). Many households plant a small plot of land around the house in order to have maize for tortillas and/or buy nixtamal handmade tortillas from women who make and sell these preferred tortillas.

At 12–13 pesos per kilo in 2011, a family consuming three kilos a day spends 39 pesos, 66 % of a daily wage.

Keleman et al. (2009) found similar trends in La Frailesca, Chiapas.

In Atlacomulco, 28 % of women older than 12 work off farm and contribute to household income; the percentage is 80 % for the Chiapas Mid and Lowlands, but 12 % for the Highlands (Survey data).

Questions referred to household consumption in the week prior to the survey: quantity of maize (own/purchased/other); use of maize flour; tortillas (homemade/purchased/other); tortillas nixtamal/maize flour.

The standard deviation for land for surplus households in maize is 3.5 for Mid and Lowland Chiapas (1.9 for Highland and 2.0 for Atlacomulco). The standard deviation for yields for surplus households is 2.7 for Mid and Lowland Chiapas, 0.8 in Highlands, and 3.4 in Atlacomulco.

Eakin et al. (2014b) show that 50 % of producers in Chiapas are maize sellers.

Data for consumption and provision of grain, flour, and tortillas was captured for the week prior to the survey. Deficit households may have grain and flour available.

Hence quality is the prerogative of relative higher income, as in the case of rich countries.

Highland Chiapas rural population is predominantly Tzeltal and Tzotzil. The rural population of Atlacomulco is predominantly Mazahua.

In the maize growing region of Sinaloa flour tortillas (wheat or maize) are mainly consumed. Criollo masa tortillas were never part of the consumption culture.

See for example, the Sin Maíz No Hay País movement; the tortilla shops established by ANEC and the Coyote Rojo initiative in the Meseta Purépecha, Michoacan (Baker 2013; Fitting 2011; McNair 2012). After years of advocacy by civil society groups, in 2011 “The right for food” has been included in the Mexican Constitution: article 4: “Every person has the right to food that is nutritious, sufficient, and of quality. The State will guarantee this” (Diario Oficial de la Nación 2011).

Abbreviations

- ANEC:

-

Asociación Nacional de Empresas Campesinas

- ASERCA:

-

Apoyos y Servicios a la Comercialización Agropecuaria

- CIMMYT:

-

Centro Internacional de Mejoramiento de Maíz y Trigo (International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center)

- CONASUPO:

-

Compañía Nacional de Subsistencias Populares

- DDR:

-

Distrito de Desarrollo Rural

- FAO:

-

Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations

- FIRCO:

-

Fideicomiso de Riesgo Compartido

- NAFTA:

-

North American Free Trade Agreement

- PROCAMPO:

-

Programa de Apoyos Directos al Campo

- PROMAF:

-

Programa de Apoyo a la Cadena Productiva de Maíz y Frijol

- SAGARPA:

-

Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería, Pesca y Alimentación

- SIAP:

-

Servicios de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera

References

Appendini, K. 2014. Reconstructing the maize market in rural Mexico. Journal of Agrarian Change 14(1): 1–25.

Appendini, K. 2012. La integración regional de la cadena maíz-tortilla. In La paradoja de la calidad. Alimentos mexicanos en América del Norte, ed. K. Appendini, and G. Rodríguez Gómez, 79–109. Mexico: El Colegio de México.

Appendini, K. 2001. De la milpa a los tortibonos. La reestructuración de la política alimentaria en México. 2nd. ed. Mexico: El Colegio de México, United Nation Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD).

Appendini, K. 1988. El papel del Estado en la comercialización de granos básicos. In Las sociedades rurales hoy, ed. J. Zepeda Patterson, 197–221. Michoacán, Mexico: El Colegio de Michoacán.

Appendini, K., R. García Barrios, and B. De la Tejera Hernández. 2003. Seguridad alimentaria y “calidad” de los alimentos: ¿una estrategia campesina? Revista Europea de Estudios Latinoamericanos y del Caribe (75) October: 65–83.

Appendini, K., L. Cortes, and V. Díaz Hinojosa. 2008. Estrategias de seguridad alimentaria en los hogares campesinos: la importancia de la calidad del maíz y la tortilla. In ¿Ruralidad sin agricultura? Perspectivas multidisciplinarias de una realidad fragmentada, ed. K. Appendini, and G. Torres-Mazuera, 103–127. Mexico: El Colegio de México.

Arslan, A., and J.E. Taylor. 2009. Farmers’ subjective valuation of subsistence crops: The case of traditional maize in Mexico. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 91(8): 957–972.

Austin, J., and G. Esteva. 1987. Food policy in Mexico. The search for self-sufficiency. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Avalos Satorio, B. 2006. What can we learn from past price stabilization policies and market reform in Mexico? Food Policy 31(4): 313–327.

Baker, L.E. 2013. Corn meets maize. Food movements and markets in Mexico. Lanham, MD: Rowan and Littlefield.

Barkin, D. 2002. The reconstruction of a modern Mexican peasantry. Journal of Peasant Studies 30(1): 73–90.

Bellon, M.R., and J. Hellin. 2011. Planting hybrids, keeping landraces: Agricultural modernization and tradition among small-scale maize farmers in Chiapas, Mexico. World Development 39(8): 1434–1443.

Contreras Molotla, F. 2014. Cambios ocupacionales en los contextos rurales de México, 2000 y 2010. PhD Dissertation. Centro de Estudios Demográficos, Urbanos y Ambientales. Mexico: El Colegio de México.

de Janvry, A., G. Gordillo, and E. Sadoulet. 1997. Mexico’s second agrarian reform. San Diego, CA: University of California, Center for US-Mexican Studies.

de Janvry, A., E. Sadoulet, and G. Gordillo. 1995. NAFTA and Mexico’s maize producers. World Development 23(8): 1349–1362.

Diario Oficial de la Nación. 2011. Tomo DCXCVII (9). Thursday 13 October 2011. www.scjn.gob.mx/normativa/…/00130217.pdf. Accessed 17 May 2015.

Dyer, G., S. Boucher, and J.E. Taylor. 2006. Subsistence response to market shocks. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 88(2): 279–291.

Eakin, H., J.C. Bausch, and S. Sweeney. 2014a. Agrarian winners of neoliberal reform: “the maize boom” of Sinaloa, Mexico. Journal of Agrarian Change 14(1): 26–51.

Eakin, H., H. Perales, K. Appendini, and S. Sweeney. 2014b. Selling maize in Mexico: The persistence of peasant farming in an era of global markets. Development and Change 45(1): 133–155.

Eakin, H., K. Appendini, S. Sweeney, and H. Perales. 2015. Correlates of maize, land, and livelihood change among maize farming households in Mexico. World Development. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.12.012.

FAO. 2012. Towards the future we want. End of hunger and make the transition to sustainable agricultural and food systems. Rome: FAO.

Fitting, E. 2011. The struggle for maize. Campesinos, workers, and transgenic maize in the Mexican countryside. Duke University Press: Durham, NC.

Fonte, M. 2002. Food systems, consumption models, and risk perception in late modernity. International Journal of Sociology of Agriculture and Food 10(1): 13–21.

Fox, J., and L. Haigh, eds. 2010. Subsidizing inequality: Mexican corn policy since NAFTA. Washington DC: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económica, University of California, Santa Cruz, CA.

Friedmann, H. 2005. From colonialism to green capitalism: Social movements and emergence of food regimes. In New directions in the sociology and development, ed. F.H. Buttel, and P. McMichael, 227–264. Binlgey, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Hewitt de Alcántara, C. ed. 1994. Economic restructuring and rural subsistence in Mexico. San Diego, CA: University of California, Center for US-Mexican Studies, United Nations Research Institute for Social Development, Centro Tepoztlán.

Isakson, S.R. 2011. Market provisioning and the conservation of crop biodiversity: An analysis of peasant livelihoods and maize diversity in the Guatemalan Highlands. World Development 39(8): 1444–1459.

Keleman, A., J. Hellin, and M.R. Bellon. 2009. Maize diversity, rural development, and farmers’ practices: Lessons from Chiapas Mexico. The Geographical Journal 175(1): 52–70.

Keleman, A., J. Hellin, and D. Flores. 2013. Diverse varieties and diverse markets: Scale-related maize “profitability crossover” in the Central Mexican Highlands. Human Ecology 41: 683–705.

Lerner, A.M., H. Eakin, and S. Sweeney. 2013. Understanding peri-urban livelihoods through an examination of maize production in the Toluca Metropolitan Area Mexico. Journal of Rural Studies 30: 52–63.

Lerner, A.M., and K. Appendini. 2011. Dimensions of peri-urban maize production in the Toluca-Atlacomulco Valley, Mexico. Journal of Latin American Geography 10(2): 87–106.

Matus Ruiz, M. 2012. Construcción de y debate sobre la calidad del quesillo artesanal oaxaqueño en Los Angeles, California. In La paradoja de la calidad. Alimentos mexicanos en América del Norte, ed. K. Appendini, and G. Rodriguez Gomez, 229–254. México: El Colegio de México.

McNair, A. 2012. La nueva normatividad agrícola y la paradoja de la calidad: un estudio de caso en Michoacán. In La paradoja de la calidad. Alimentos mexicanos en América del Norte, ed. K. Appendini, and G. Rodríguez Gómez, 143–172. Mexico: El Colegio de México.

Murdoch, J., T. Marsden, and J. Banks. 2000. Quality, nature, and embeddedness: Some theoretical considerations in the context of the food sector. Economic Geography 76(2): 107–125.

Perales, R.H., B.F. Benz, and S.B. Brush. 2005. Maize diversity and ethnolinguistic diversity in Chiapas, Mexico. PNAS 102(3): 949–954.

Perales, R.H., and S.B. Brush. 2007. A maize landscape: Ethnicity and agro-biodiversity in Chiapas Mexico. Agriculture, Ecosystem, and Environment 121: 211–221.

Preibisch, L.K., G. Rivera Herrejón, and S.L. Wiggins. 2002. Defending food security in a free-market economy. The gendered dimensions of restructuring in rural Mexico. Human Organization 61(1): 68–79.

Prigent-Semovin, A., and C. Herault-Fournier. 2005. The role of trust in the perception of quality of local food products: With particular reference to direct relationships between producer and consumer. Anthropology of Food 4. http://aof.revues.org/204?lang=fr. Accessed 13 March 2013.

Puyana, A., and J. Romero. 2005. Diez años con el TLCAN. Las experiencias del sector agropecuario mexicano. Mexico: El Colegio de México, Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Mexico.

Rello, F., and F. Saavedra. 2010. Cambios estructurales de las economías rurales en la globalización. RuralStruc Program. Phase II. Washington, DC: World Bank, French Cooperation, International Fund for Agricultural Development.

Rodríguez Gómez, G. 2012. La calidad en los sistemas agroalimentarios en América del Norte. In La paradoja de la calidad. Alimentos mexicanos en América del Norte, ed. K. Appendini, and G. Rodríguez Gómez, 19–24. Mexico: El Colegio de México.

Rubio, B. (ed.). 2013. La crisis alimentaria mundial. Impacto sobre el campo mexicano. Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México and Miguel Angel Porrúa.

SAGARPA and ASERCA. 2013. Programa de prevención y manejo de riesgos apoyo al ingreso objetivo y a la comercialización. Informe de resultados al cuarto trimestre ejercicio fiscal 2012. Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería, Pesca y Alimentación and Agencia de Servicios a la Comercialización y Desarrollo de Mercados Agropecuarios: México. http://aserca.gob.mx/riesgos/trimestrales/Documents/2012/informe_al_cuarto_trimestre_2012_3.pdf. Accessed 16 March 2015.

SAGARPA and CIMMYT. 2012. MasAgro ¿Cómo puede México producir alimentos para una población que crece a ritmo acelerado y en un momento en que el cambio climático hace parecer al futuro más incierto y desalentador que nunca? Mexico: Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería, Pesca y Alimentación and Centro Internacional de Mejoramiento de Maíz y Trigo. http://repository.cimmyt.org/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10883/1374/97930.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed 20 Aug 2014.

SAGARPA and FIRCO. 2012. Memoria documental PROMAF2010. Fideicomiso de riesgo compartido proyecto estratégico de apoyo a la cadena productiva de los productores de maíz y frijol (PROMAF 2010). http://www.firco.gob.mx/POTTtransparencia/Documents/MemoriasDocumentales/firco_md_promaf10%20doc%20publico.pdf. Accessed 8 April 2014.

SAGARPA-SIAP. 2015. Producción agrícola. Ciclo: Año agricola OI + PV 2012. Modalidad: Riego + temporal. Maíz grano. http://www.siap.gob.mx/cierre-de-la-produccion-agricola-por-estado/. Accesed 15 May 2015.

Secretaría de Economía. 2012. Análisis de la cadena de valor maíz-tortilla: Situación actual y factores de competencia local. Dirección General de Industrias Básicas. http://www.economia.gob.mx/files/comunidad_negocios/industria_comercio/informacionSectorial/20120411_analisis_cadena_valor_maiz-tortilla.pdf. Accessed 9 Sept 2014.

Secretaría de Salud. 2002. NORMA Oficial Mexicana NOM-188-SSA1-2002, Productos y Servicios. Control de aflatoxinas en cereales para consumo humano y animal. Especificaciones sanitarias. http://www.salud.gob.mx/unidades/cdi/nom/188ssa12.html. Accessed 9 April 2014.

Sweeney, S., D. Steigerwald, F. Davenport, and H. Eakin. 2013. Mexican maize production: evolving organizational and spatial structures since 1980. Applied Geography 39: 78–92.

Terragni, L., M. Boström, B. Halkier, and J. Mäkela. 2009. Can consumers save the world? Everyday food consumption and dilemmas of sustainability. Anthropology of Food S5. http://aof.revues.org. Accessed 28 May 2015.

Torres-Mazuera, G. 2008. Transformación identitaria en un ejido rural del centro de México. Reflexiones en torno a los cambios culturales en el nuevo contexto rural. In ¿Ruralidad sin agricultura? Perspectivas multidisciplinarias de una realidad fragmentada, ed. K. Appendini, and G. Torres-Mazuera, 239–254. Mexico: El Colegio de Mexico.

Turrent Fernandez, A., T.A. Wise, and G. Garvey. 2012. Factibilidad de alcanzar el potencial productivo de maíz en México. Mexican Rural Research Report No. 24. Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

World Bank. 2007. World development report 2008. Agriculture for development. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Yúnez Naude, A., J.E. Taylor, and J. Becerril García. 2000. Los pequeños productores rurales: características y análisis de impactos. In Los pequeños productores rurales en México: las reformas y las opciones, ed. A. Yúnez Naude, 101–137. El Colegio de México: México.

Acknowledgments

This paper is part of the research project “Market Integration and climate as the drivers of change in the Mexican Maize system.” This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant no. 0826871. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation (NFS). The authors sincerely appreciate the valuable comments from Hallie Eakin, Amy Lerner, Hugo Perales, and Cynthia Hewitt de Alcántara as well as two anonymous reviewers and thank the editor for his helpful guidance to finish this paper. Also, our thanks to Georgina Ortiz and Jaime Muñoz, for working the data, and to Fernando M. Pérez, who supported fieldwork in Chiapas. The authors are fully responsible for the final results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Appendini, K., Quijada, M.G. Consumption strategies in Mexican rural households: pursuing food security with quality. Agric Hum Values 33, 439–454 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-015-9614-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-015-9614-y