Abstract

The mini-clinical evaluation exercise (mini-CEX) is a well-established method of assessing trainees’ clinical competence in the workplace. In order to improve the quality of clinical learning, factors that influence the provision of feedback are worthy of further investigation. A retrospective data analysis of documented feedback provided by assessors using the mini-CEX in a busy emergency department (ED) was conducted. The assessors comprised emergency physicians (EPs) and trauma surgeons. The trainees were all postgraduate year one (PGY1) residents. The completion rate and word count for each of three feedback components (positive feedback, suggestions for development, and an agreed action plan) were recorded. Other variables included observation time, feedback time, the format used (paper versus computer-based), the seniority of the assessor, the gender of the assessor and the specialty of the assessor. The components of feedback provided by the assessors and the influence of these contextual and demographic factors were also analyzed. During a 26-month study period, 1101 mini-CEX assessments (from 273 PGY1 residents and 67 assessors) were collected. The overall completion rate for the feedback components was 85.3 % (positive feedback), 54.8 % (suggestions for development), and 29.5 % (agreed action plan). In only 22.9 % of the total mini-CEX assessments were all three aspects of feedback completed, and 7.4 % contained no feedback. In the univariate analysis, the mini-CEX format, the seniority of the assessor and the specialty of the assessor were identified as influencing the completion of all three components of feedback. In the multivariate analysis, only the mini-CEX format and the seniority of the assessor were statistically significant. In a subgroup analysis, the feedback-facilitating effect of the computer-based format was uneven across junior and senior EPs. In addition, feedback provision showed a primacy effect: assessors tended to provide only the first or second feedback components in a busy ED setting. In summary, the authors explored the influence of gender, seniority and specialty on paper and computer-based feedback provision during mini-CEX assessments for PGY1 residency training in a busy ED. It was shown that junior assessors were more likely to provide all three aspects of written feedback in the mini-CEX than were senior assessors. The computer-based format facilitated the completion of feedback among EPs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The mini-clinical evaluation exercise (mini-CEX) is a well-known reliable method of assessing trainees’ clinical competence in the workplace (Kogan et al. 2009; Al Ansari et al. 2013; Alves de Lima et al. 2013). It was introduced into the Taiwanese medical education system 10 years ago and has been widely integrated into medical education curriculums since then (Chen et al. 2005; Liao et al. 2013). Uniquely, it is the number and breadth of the structured feedback comments that make the mini-CEX a rich assessment tool (Pernar et al. 2011). Receiving appropriate feedback promotes the identification of strengths and weaknesses within trainees’ clinical competencies, which is crucial for effective teaching and learning (Carr 2006). Previous studies have documented the advantages of feasibility and utility of the mini-CEX for promoting feedback in a clinical workplace setting (Kogan et al. 2002; Wiles et al. 2007; Weller et al. 2009). However, not all trainees report receiving useful feedback, and in some cases, feedback provided by assessors may be poor (Fernando et al. 2008; Cohen et al. 2009). Thus, in order to improve the quality of clinical learning, factors that influence the provision of feedback are worth further investigation.

The digitalization of assessment tools in order to make workplace teaching and learning more efficient has become a worldwide trend. One randomized controlled study found that by modifying the format and process of the assessment tool, more recorded observations were made and assessor accuracy improved (Donato et al. 2008). Furthermore, both personal digital assistant (PDA)- and paper-based mini-CEX assessments have demonstrated high reliability (Torre et al. 2011). However, studies examining the correlation between digitalization and the provision of feedback in mini-CEX assessments are few (Torre et al. 2007, 2011). In this study, we aimed to explore the factors influencing the provision of feedback, including the influence of a computer-based format on the provision of feedback.

Materials and methods

Study design

Our study comprised a retrospective data analysis of the influence of contextual and demographic factors on the provision of feedback by assessors using the mini-CEX to evaluate the clinical competency of trainees in an emergency department (ED). The evaluations were conducted in the ED of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (CGMH), a 3800-bed tertiary hospital in Taoyuan, Taiwan. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital.

Participants

The assessors comprised emergency physicians (EPs) and trauma surgeons. The trainees were all postgraduate year one (PGY1) residents. According to the regulations of the Ministry of Health, all medical students should have a 1-year rotation after graduation and before choosing their own specialty. In addition to emergency medicine, the one-year rotation curriculum also includes internal medicine, gynecology/obstetrics, pediatrics, general surgery, community medicine and a number of months in the specialty of their choosing. Each PGY1 resident received a curriculum of 1 week of trauma emergency training and 3 weeks of non-trauma emergency training during the one-month ED rotation. A total of 67 assessors (50 EPs and 17 trauma surgeons) evaluated 273 PGY1 residents during their emergency medicine training.

Data collection

The data was collected between November 2009 and December 2011. The mini-CEX used was in a traditional Chinese format that has been previously validated (Chen et al. 2006). In the mini-CEX, a single assessor observes the trainee conducting a focused history-taking and physical examination. The trainee then presents any differential diagnoses and/or a management plan. The seven itemized clinical competencies (medical interviewing, physical examination, clinical skills, counseling skills, clinical judgment, organization/efficiency, and professionalism) are rated using a nine-point rating scale (1 = unsatisfactory and 9 = superior). This scaling was used as it is believed to provide greater accuracy (Cook and Beckman 2009). In our study, feedback was given to the trainees at the end of the mini-CEX as part of the workplace assessment. Feedback included three components: positive feedback (particular strengths), suggestions for development, and an agreed educational plan of action. Feedback time was estimated by the assessor and recorded on the mini-CEX form. The mini-CEX was completed weekly to evaluate the clinical competency of PGY1 doctors. However, PGY1 doctors were allowed to request additional mini-CEXs if they wished to receive more assessment and feedback on their performance during the ED rotation.

For the first 9 months, the mini-CEX and the feedback were provided to all trainees using a paper-based format. Over the following 17 months, the mini-CEX and feedback provided by the EPs shifted to a computer-based format, while those provided by the trauma surgeons remained in the paper-based format. The computer-based format was not provided for trauma surgeons due to lack of funding. The content of the different formats was identical.

When a computer-based format was used, immediately after evaluating the patient, the assessor and the trainee sat in front of a computer that ran the ED teaching support software. The computer format was easily accessible for EPs in the emergency department. The mini-CEX data were collected by a program assistant in the residency training office using a standard procedure.

Data analysis

We analysed the mean age of patients, the seniority of the assessor, the observation time, the feedback time, the gender of the assessor, the specialty of the assessor, the completion rate of each domain of clinical competency, the word count (in Chinese) used for feedback on each component, and the impact of the format used on the provision of all three aspects of feedback. We also analyzed the frequency of use for each feedback component (positive feedback, suggestions for development and an agreed plan of action), of all feedback components and of no feedback for weekly mini-CEXs. When comparing results between two groups, where appropriate, a χ 2 test or a Fisher’s exact test was applied for the categorical data. A two-tailed independent t test was used for the continuous variables. Bonferroni correction was applied to adjust multiple comparisons. Univariate and multivariate logistic regressions were used to identify possible correlates influencing the provision of all three aspects of feedback. Data were analyzed using SAS statistical software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Alpha was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Overall

A total of 1101 mini-CEX ratings of PGY1 residents were completed during the study period. During the study period, EPs rated 899 PGY1-patient encounters and trauma surgeons rated 202 PGY1-patient encounters. The EP-rated mini-CEXs comprised 295 paper-format evaluations and 604 computer-format evaluations. The overall completion rates for the components of positive feedback, suggestions for development and agreed action plan were 85.3, 54.8, and 29.5 %, respectively. Only 22.9 % of the total mini-CEXs contained all three components of feedback, while 7.4 % of mini-CEXs were without any feedback.

Quality analysis of feedback completed by faculties with different specialties

Feedback was provided on 878 (97.7 %) mini-CEXs rated by emergency physicians and on 142 (70.3 %) mini-CEXs rated by trauma surgeons. Using the paper format of the mini-CEX in the ED, the feedback time was longer when PGY1 residents were rated by trauma surgeons than when they were rated by EPs (Table 1). Except for clinical skills, the completion rate for other domains of clinical competency was similar for the EPs and trauma surgeons when the paper-based format was used.

The word counts of the feedback for each of the three components were similar for EPs and trauma surgeons. However, the absolute percentages of the three feedback components used (positive feedback, suggestions for development and an agreed action plan) were higher for the EP group: 89.2, 57.0 and 28.1 %, respectively when provided by EPs; and 67.3, 33.2 and 12.9 %, respectively when provided by trauma surgeons. Feedback containing all three components was provided on 19.0 % of the assessments by EPs and on 12.4 % of those completed by trauma physicians. Only 5.1 % of assessments completed by EPs, but 29.7 % of those by trauma surgeons, provided no feedback at all.

Comparing feedback on mini-CEXs using different formats

After a computer-based mini-CEX was implemented, EPs were requested to complete mini-CEXs in this format. The computer-based format contained exactly the same components as the paper-based format. The mean age of patients, observation time, feedback time and gender of the examinees were similar for both formats. However, the seniority of the assessor was greater and a higher proportion of men were in the group using the paper-based format. As it was decided that PGY1 doctors would be free to choose their assessors in the clinical placement setting, a selection bias could have resulted due to their choices.

In the clinical domain of competency, efficiency/organization and professionalism were evaluated more often using the computer-based format than using paper-based format (94.6 vs. 99.2 %, p < 0.001 and 93.9 vs. 99.3 %, p < 0.001, respectively). Clinical skills were evaluated more often using the paper-based format than using computer-based format (48.8 vs. 11.9 %). The difference between clinical skills’ results and other results is related to the interference of the implementation of direct observation of procedural skill (DOPS), which explained the reduction in the frequency of assessing technical skills in the mini-CEX. Therefore, it made no sense to compare the completion rates for the clinical skill assessment across the paper- and computer-based different formats.

EPs who used the paper-format mini-CEX provided more feedback for positive feedback than those used the computer-based format (a mean word count of 11.40 ± 7.31 vs. 8.98 ± 6.62, p < 0.001), while more feedback was provided using the computer-based format than paper-based format for agreed action plans (mean word count 12.8 ± 8.88 vs. 9.2 ± 5.1, p < 0.001; frequency of feedback component used 35.8 % vs. 28.1 %, p = 0.023). Feedback containing all three components was provided by 28.3 % of the mini-CEXs using the computer-based format and 19.0 % of mini-CEXs using the paper-based format (Table 1).

Factors associated with the provision of all aspects of feedback

The factors associated with the provision of all aspects of feedback during a mini-CEX evaluation in an ED are shown in Table 2. In the univariate analysis, the seniority of the assessor [odds ratio (OR) 0.41; 95 % CI 0.29–0.58], the mini-CEX format (OR 2.03; 95 % CI 1.51–2.73) and the specialty of the assessor (OR 2.39; 95 % CI 1.53–3.73) were statistically significant. However, in the multivariate logistic regression in which all covariates were adjusted, only the seniority of the assessor (OR 0.35; 95 % CI 0.24–0.51) and the mini-CEX format (OR 1.47; 95 % CI 1.01–2.15) were statistically significant. The results suggest that a computer-format evaluation and physicians with fewer than 10 years of seniority are more likely to complete all three aspects of feedback.

Subgroup analysis of age versus computer format

We further conducted a subgroup analysis of emergency physicians who used computer formats to determine the difference between junior and senior EPs in using computers as rating tools. We categorized EPs into junior and senior groups by seniority with a cut-off point of 10 years. Longer feedback times were observed for mini-CEXs provided by junior EPs than for those by seniors. Junior EPs also provided a significantly higher portion of all three aspects of feedback (37.1 %) than did seniors (8.60 %, p < 0.001) when using the computer format. Two of the feedback components, suggestions for development and an agreed action plan, were also used significantly more often by junior EPs than by seniors (Table 3).

Discussion

Recently, it has been continually emphasized in the literature that formative assessments such as the mini-CEX could be used as a tool for optimizing learning in a medical education context (Schuwirth 2013). The health professions are expected to nurture recipient reflection-in-action for achieving truly effective feedback (Archer 2010). However, fewer than a quarter of the mini-CEXs (22.9 %) recorded all aspects of feedback in our study. Moreover, some of the mini-CEXs were void of feedback, probably due to our busy ED setting. Indeed, Kogan et al. (2012) pointed out that provision of feedback is a complex and dynamic process influenced by many factors. Previous studies have also shown that provision of effective feedback in healthcare education can be problematic and that some barriers to giving feedback exist, namely, under using interactive the feedback methods of self-assessment and action plans (Holmboe et al. 2004; Colthart et al. 2008). Some new models of feedback in higher and professional education have addressed the impact of culture and continuum on complex and contextual feedback (Archer 2010; Boud and Molloy 2013) Therefore, we decided to explore the influence of contextual and demographic factors on the provision of feedback during mini-CEX assessments in an emergency department.

Several factors have been identified as influential in giving feedback, such as the specialty, the assessor group, the self-confidence of the assessor in his or her clinical and feedback skills and whether or not the assessor is an academic trainee (Fernando et al. 2008; Kogan et al. 2012). In our study, the seniority of the assessor and the computer-based format used were considered individually as negative and positive influential factors in giving feedback to learners in the ED. Compared with the itemized rating section, providing written feedback is usually more time-consuming. Li et al. (2016) evaluated EP efficiency in the Taiwanese healthcare system. They found that senior EPs take longer than junior EPs when ordering prescriptions and patient disposition in treating both urgent and non-urgent patients (Li et al. 2016). It is likely that some of the written feedback components were possibly omitted for these reasons in our busy ED.

No previous studies have been conducted to directly compare feedback obtained via different formats. Our results suggest that a computer-based format facilitates the provision of feedback in a mini-CEX evaluation across EPs. Indeed, focusing on the rating process rather than on the feedback, Torre et al. (2011) found similar results following the digitalization of the mini-CEX format. However, the rating process requires considerably less typing/writing than does the feedback process. Since for most people, typing is faster than handwriting, our results favor the use of a computer-based format for faster feedback provision. This would have obvious benefits in a busy ED setting for EPs and might also be applicable for mini-CEX assessments in other disciplines.

In our study, the electronic format of the mini-CEX had an uneven effect on facilitating feedback from senior and junior assessors. Feedback time and most of the completion rates were significantly higher among junior EPs than among seniors. Similar results have also been found in previous studies comparing mini-CEXs with paper-based and personal digital assistant (PDA)-based formats (Torre et al. 2007, 2011). This is possibly because junior faculty are likely to be more familiar with the operation of a computer interface in the assessment and feedback process than are seniors. From this perspective, we propose that, although the computer format generally facilitates the provision of the feedback, some barriers to its usage among senior assessors may exist (McLeod et al. 2003; Torre et al. 2011).

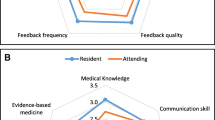

In this study, approximately 85.3 % of the assessors completed the complimentary part of the feedback, positive feedback. In contrast, only 54.8 % provided suggestions for development and 29.5 % provided an agreed action plan individually. The completion rate of each feedback component decreased in accordance with its order of presentation, which has also been found in previous studies (Fernando et al. 2008; Pelgrim et al. 2012). This phenomenon in our study could be a primacy effect: in a busy ED setting, some assessors tend to complete only the first or second feedback component, especially in situations of clinical overload or high stress. This can be inferred from Fig. 1. A previous study also revealed that the observation and evaluation times allotted to an EM faculty member are often limited (Chisholm et al. 2004). Another possible explanation is that, culturally, most people are unwilling to point out another’s weaknesses face to face, even if such an interaction takes place between a teacher and a trainee (Colletti 2000).

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, it is a retrospective data analysis and a selection bias could have resulted. Second, we did not incorporate environmental factors, such as ED crowding and the emergency physician’s clinical load. These factors are difficult to quantify but can influence the quality of a mini-CEX assessment. Third, we simply quantified the completion rate and word count of the feedback given by the assessors, instead of qualitatively analyzing the contents of the feedback. One could argue that the provision of all three components might not necessarily equate to high-quality feedback. Fourth, the trauma surgeons did not start with the computer format due to lack of funding. Fifth, it was decided that PGY1 trainees would be free to choose their assessors in the clinical placement setting; accordingly, a selection bias could have resulted. Sixth, the implementation of direct observation of procedural skill (DOPS) explains a reduction in the frequency of assessing technical skills in the mini-CEX. Therefore, it made no sense to compare the completion rate of clinical skill assessment using different formats. Finally, it is very likely that some of the communication between trainees and assessors was not documented in the mini-CEX form; further investigation is needed to evaluate the gap between verbal feedback and written feedback.

Conclusion

Our study analyzed the provision of feedback in mini-CEX assessments during PGY1 resident ED rotations. Junior assessors were more likely to provide all three aspects of feedback than were senior assessors. A computer-based format facilitated the completion of feedback, especially on the part of junior assessors among EPs. Additional studies are needed to qualitatively analyze differences and to consider the effects of computer-based formats used by other specialized doctors.

References

Al Ansari, A., Ali, S. K., & Donnon, T. (2013). The construct and criterion validity of the mini-CEX: A meta-analysis of the published research. Academic Medicine, 88(3), 413–420.

Alves de Lima, A., Conde, D., Costabel, J., Corso, J., & Van der Vleuten, C. (2013). A laboratory study on the reliability estimations of the mini-CEX. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 18(1), 5–13.

Archer, J. C. (2010). State of the science in health professional education: Effective feedback. Medical Education, 44(1), 101–108.

Boud, D., & Molloy, E. (2013). Feedback in higher and professional education: Understanding it and doing it well. Oxon: Routledge.

Carr, S. (2006). The Foundation Programme assessment tools: An opportunity to enhance feedback to trainees? Postgraduate Medical Journal, 82(971), 576–579.

Chen, W., Tsai, C. H., & Huang, K. Y. (2005). Clinical medical education and mini-CEX (clinical evaluation exercise). Journal of Medical Education, 9(4), 74–81.

Chen, W., Lin, C. C., Huang, C. C., Tsai, C. H., & Tsai, C. H. (2006). Implementation of the mini-CEX (clinical evaluation exercise): Experiences and preliminary results. Journal of Medical Education, 10(3), 232–239.

Chisholm, C. D., Whenmouth, L. F., Daly, E. A., Cordell, W. H., Giles, B. K., & Brizendine, E. J. (2004). An evaluation of emergency medicine resident interaction time with faculty in different teaching venues. Academic Emergency Medicine, 11(2), 149–155.

Cohen, S. N., Farrant, P. B., & Taibjee, S. M. (2009). Assessing the assessments: U.K. dermatology trainees’ views of the workplace assessment tools. British Journal of Dermatology, 161(1), 34–39.

Colletti, L. M. (2000). Difficulty with negative feedback: Face-to-face evaluation of junior medical student clinical performance results in grade inflation. Journal of Surgical Research, 90(1), 82–87.

Colthart, I., Bagnall, G., Evans, A., Allbutt, H., Haig, A., Illing, J., et al. (2008). The effectiveness of self-assessment on the identification of learner needs, learner activity, and impact on clinical practice: BEME Guide no. 10. Medical Teacher, 30(2), 124–145.

Cook, D. A., & Beckman, T. J. (2009). Does scale length matter? A comparison of nine- versus five-point rating scales for the mini-CEX. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 14(5), 655–664.

Donato, A. A., Pangaro, L., Smith, C., Rencic, J., Diaz, Y., Mensinger, J., et al. (2008). Evaluation of a novel assessment form for observing medical residents: A randomised, controlled trial. Medical Education, 42(12), 1234–1242.

Fernando, N., Cleland, J., McKenzie, H., & Cassar, K. (2008). Identifying the factors that determine feedback given to undergraduate medical students following formative mini-CEX assessments. Medical Education, 42(1), 89–95.

Holmboe, E. S., Yepes, M., Williams, F., & Huot, S. J. (2004). Feedback and the mini clinical evaluation exercise. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 19(5 Pt 2), 558–561.

Kogan, J. R., Bellini, L. M., & Shea, J. A. (2002). Implementation of the mini-CEX to evaluate medical students’ clinical skills. Academic Medicine, 77(11), 1156–1157.

Kogan, J. R., Holmboe, E. S., & Hauer, K. E. (2009). Tools for direct observation and assessment of clinical skills of medical trainees: A systematic review. JAMA, 302(12), 1316–1326.

Kogan, J. R., Conforti, L. N., Bernabeo, E. C., Durning, S. J., Hauer, K. E., & Holmboe, E. S. (2012). Faculty staff perceptions of feedback to residents after direct observation of clinical skills. Medical Education, 46(2), 201–215.

Li, C. J., Syue, Y. J., Tsai, T. C., Wu, K. H., Lee, C. H., & Lin, Y. R. (2016). The impact of emergency physician seniority on clinical efficiency, emergency department resource use, patient outcomes, and disposition accuracy. Medicine (Baltimore), 95(6), e2706.

Liao, K. C., Pu, S. J., Liu, M. S., Yang, C. W., & Kuo, H. P. (2013). Development and implementation of a mini-clinical evaluation exercise (mini-CEX) program to assess the clinical competencies of internal medicine residents: From faculty development to curriculum evaluation. BMC Medical Education, 13, 31.

McLeod, T. G., Ebbert, J. O., & Lymp, J. F. (2003). Survey assessment of personal digital assistant use among trainees and attending physicians. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 10(6), 605–607.

Pelgrim, E. A., Kramer, A. W., Mokkink, H. G., & Van der Vleuten, C. P. (2012). Quality of written narrative feedback and reflection in a modified mini-clinical evaluation exercise: An observational study. BMC Medical Education, 12, 97.

Pernar, L. I., Peyre, S. E., Warren, L. E., Gu, X., Lipsitz, S., Alexander, E. K., et al. (2011). Mini-clinical evaluation exercise as a student assessment tool in a surgery clerkship: Lessons learned from a 5-year experience. Surgery, 150(2), 272–277.

Schuwirth, L. (2013). Making the horse drink: Use of mini-CEX in an assessment for learning view. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 18(1), 1–4.

Torre, D. M., Simpson, D. E., Elnicki, D. M., Sebastian, J. L., & Holmboe, E. S. (2007). Feasibility, reliability and user satisfaction with a PDA-based mini-CEX to evaluate the clinical skills of third-year medical students. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 19(3), 271–277.

Torre, D. M., Treat, R., Durning, S., & Elnicki, D. M. (2011). Comparing PDA- and paper-based evaluation of the clinical skills of third-year students. WMJ, 110(1), 9–13.

Weller, J. M., Jolly, B., Misur, M. P., Merry, A. F., Jones, A., Crossley, J. G., et al. (2009). Mini-clinical evaluation exercise in anaesthesia training. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 102(5), 633–641.

Wiles, C. M., Dawson, K., Hughes, T. A., Llewelyn, J. G., Morris, H. R., Pickersgill, T. P., et al. (2007). Clinical skills evaluation of trainees in a neurology department. Clinical Medicine, 7(4), 365–369.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by Department of Emergency Medicine of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital and Chang Gung Medical Education Research Center (CGMERC). All authors thank Professor Lynn Monrouxe for her help in manuscript revision and English editing for improving the quality of this article.

Author Contributions

YCC and CHC contributed to the design of the study and the draft of the article. CHC is responsible for the statistical analysis. CKC, CHL1, and CHL2 contributed to the acquisition and interpretation of the data and also to the critical revision of the manuscript. CJN and JCC are responsible for postgraduate year one (PGY1) curriculum design and contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. (Abbreviations: CHL1: Ching-Hsing Lee; CHL2: Chien-Hung Liao)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, YC., Lee, CH., Chen, CK. et al. Exploring the influence of gender, seniority and specialty on paper and computer-based feedback provision during mini-CEX assessments in a busy emergency department. Adv in Health Sci Educ 22, 57–67 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-016-9682-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-016-9682-9