Summary

Modern macroeconomics has failed in the analysis of both the US banking and the euro crises, respectively, and there is also a rather inadequate view on a range of relevant policy issues. The approach presented herein looks at the reasons for analytical failure and suggests means of improvement – picking up proposals from the literature as well as contributing new ones. The economics profession did not anticipate the banking crisis and there is reluctance to switch to a new paradigm for stabilization policy analysis. Beyond this, there are several analytical challenges which should be integrated into a post-crisis approach: for example, the question of the true degree of economic openness and the role of multinational companies. Moreover, the macroeconomic impact of the digital economic expansion is largely underestimated. The traditional view on asset bubbles has become doubtful. A new paradigm should emphasize the triple analytical challenge of short-term financial market analysis, the routine new questioning of the systemic stability of economic systems and standard macroeconomic modeling – with some refinements; a “Schumpeterian Mundell-Fleming-Solow-Akerlof-model” and sustainability aspects are important on the one hand, on the other hand NKM models have to integrate a broader array of market imperfections. The perspectives presented could jump-start a new paradigm that combines a more realistic macro perspective with a complementary critical institutional analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Akerlof GA (1970) The Market for Lemons: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism. Q J Econ 84:488–500

Artus P, Virard MP (2005) le capitalism est en train de s’autodétruire (Capitalism on the Way to Self-Destruction), Paris: Edition La Découverte

Barrel R, Pain N (1997) Foreign Direct Investment, Technological Change, and Economic Growth within Europe. Econ J 107:1770–1786

Becker B, Milbourn T (2010) How did increased competition affect credit ratings? Harvard Business School Working Paper 09–051

Bernanke BS, Gertler M (1989) Agency costs, net worth, and business fluctuations. Am Econ Rev 79:14–31

Bernanke BS, Gertler M, Gilchrist S (1999) The Financial accelerator in a quantitative business cycle frameworks. In: Taylor JB, Woodford M (eds) Handbook of Macroeconomic Edition 1, vol 1, Chapter 21. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 1341–1393

BIS (1986) Recent innovations in international banking, Basel

Branson WH (1977) Asset markets and relative prices in exchange rate determination. Sozialwissenschaaftliche Annalen 1:69–89

Bretschger L, Hettich F (2002) Globalisation, capital mobility and tax competition: theory and evidence for OECD countries. Eur J Polit Econ 18(4):695–716

Brunnermeier MK (2014) Das letzte Kapital ist noch nicht geschrieben (Interview). Perspekt Wirtsch 15:234–245

Calomiris CW (2009) Banking Crises Yesterday and Today. The PEW Briefing Paper No. 8, Washington DC.

Campbell J, Mankiw G (1990) Permanent income, current income, and consumption. J Bus Econ Stat 8:265–279

Carlstrom C, Fuerst T (1997) Agency costs, net worth, and business fluctuations: a computable general equilibrium analysis. Am Econ Rev 87:893–910

Carrol CD, Dunn WE (1997) Unemployment expectations, jumping triggers and household balance sheets. NBER Macroecon Annu 1997

Christiano LJ, Eichenbaum M, Evans CL (2005) Nominal rigidities and the dynamic effects of a shock to monetary policy. J Polit Econ 113(1):1–46

Davis MA, Heathcote J (2005) Housing and the business cycles. Int Econ Rev 46(3):751–784

Deutsche Bundesbank (2010) Yields on bonds under safe haven effects. Monthly Report October 2010: 30–31

Dooley M, Hutchison M (2009) Transmission of the U.S. subprime crisis to emerging markets: evidence on the decoupling-recoupling hypothesis. The JIMF/Warwick Conference, April 6th, 2009

Field AJ (1984) A New Interpretation of the Onset of the Great Depression. J Econ Hist 44:489–498

Filardo A (2001) Should monetary policy respond to asset price bubbles? Some experimental results. In: Kaufman G (ed) Asset price bubbles: Implications for monetary and regulatory policies. Elsevier Science, Amsterdam

Fisher I (1933) The Debt-deflation theory of great depression. Econometrica 337–357

Froot KA, Stein JC (1991) Exchange rates and foreign direct investment: an imperfect capital markets approach. Quart J Econ 106(4):1191–1217

Eichengreen B, Barkbu B, Mody A (2011) International Financial Crises and the Multilateral Response: What the Historical Record Shows. Global Financial Crisis National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc., NBER Chapters

Goodhart CAE (2008) The background to the 2007 financial crisis. Int Econ EconPolicy 4(4):331–346

Hirschman AO (1970) Exit, voice and loyalty. Response to decline in firms, organizations and states. Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA

Hubbard RG (1998) Capital-Market Imperfections and Investment. J EconLit, Am Econ Assoc 36(1):193–225

Iacoviello M (2004) Consumption, house prices and collateral constraints: a structural econometric analysis. J Hous Econ 13(4):304–320

Iacoviello M (2005) House prices, borrowing constraints and monetary policy in the business cycle. Am Econ Rev 95(3):739–764

Iacoviello M, Neri S (2007) Housing market spillovers: Evidence from an estimated DSGE model. Boston College Working Papers in Economics no. 659

IMF (2006) Ireland: Financial System Stability Assessment Update. Washington DC

Issing O (2009) Asset prices and monetary policy. The Cato Journal, Winter

Jappelli T, Pagano M (1989) Consumption and capital market imperfections: An international comparison. Am Econ Rev 79(5):1088–1105

Jorgenson DW, Ho MS, Stiroh KJ (2005) Productivity – Information technology and the American growth resurgence. MIT Press, Cambridge

Jungmittag A, Welfens PJJ (2009) Liberalization of EU telecommunications and trade: theory, gravity equation analysis and policy implications. J of Int Econ Econ Policy 6:23–39

Kiyotaki N, Moore J (1997) Credit cycles. J Polit Econ 105:211–248

Kollman R, Roeger W, In’tVeld J (2012) Fiscal Policy in a Financial Crisis: Standard Policy vs Bank Rescue Measures. ECARES Working Paper 2012–008

Menden, A (2014) Ganz schön berechnend, Süddeutsche Zeitung, Munich, 3.8.2014, p. 11

Rajan RG (2005) Has financial development made the world riskier? NBER Working Paper No. 11728

Shiller RJ (2000) Irrational Exuberance. Press, Princeton University

Shiller RJ (2003) From Efficient Markets Theory to Behavioral Finance, Cowles Foundation Paper No. 1055, New Haven: Connecticut

Smets F, Wouters R (2007) Shocks and frictions in U.S. Business Cycles. Am Econ Rev 97(3):586–606

UNCTAD (2014) World Investment Report 2014. York, New

Villaverde JF, Garicano L, Santos T (2013) Political credit cycles: The case of the Eurozone. J Econ Perspect 27:145–166

Wagner H (2010) The causes of the recent financial crisis and the role of central banks in avoiding the next one, International Economics and Economic Policy, vol. 7, No. 1, 2010, pp. 63–82

Welfens PJJ (2009) Transatlantische Bankenkrise. Lucius, Stuttgart

Welfens PJJ (2010) Transatlantic banking crisis: analysis, rating, policy issues. IEEP 7(1):3–48

Welfens, PJJ (2011a) Innovations in Macroeconomics, 3rd revised edition, Heidelberg and New York

Welfens PJJ (2011b) The Transatlantic Banking Crisis: Lessons, Reforms and G20 Issues. In: Welfens PJJ, Ryan C (eds) Financial Market Integration and Growth – Structural Change and Economic Dynamics in the European Union. Springer, Heidelberg, pp 27–48

Welfens, PJJ (2012), Marshall-Lerner condition and economic globalization, International Economics and Economic Policy, Vol. 9 (2), June 2012, pp. 191-207

Welfens PJJ (2013) Social Security and Economic Globalization. Springer, Heidelberg and New York

Welfens PJJ, Perret JK (2014) Information & communication technology and true real GDP: economic analysis and findings for selected countries, International Economics and Economic Policy, vol 11 (1-2), pp 5–27

Welfens PJJ, Irawan T (2014). European innovation dynamics and US economic impact: theory and empirical analysis. IZA Discussion Paper Series No. 8507

Welfens PJJ, Perret JK, Erdem D (2010) Global Economic Sustainability Indicator: Analysis and Policy Options for the Copenhagen Process. J Int Econ EconPolicy 7(2):153–185

Zeldes SP (1989) Consumption and liquidity constraints: an empirical investigation. J Polit Econ 97(2):305–346

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

I gratefully appreciate the research assistance of Evgeniya Yushkova, Tony Irawan, Vladimir Udalov, Jens Perret and Arthur Korus (EIIW). I also appreciate editorial support by David Hanrahan, Schumpeter School of Business and Economics at the University of Wuppertal. An earlier version of this paper was presented as a keynote speech at a workshop of the symposium jointly held by the Center for Macroeconomic Research, Xiamen University and Springer Science, Heidelberg, on September 12, 2014. I also benefitted from my presentation on the Transatlantic Banking Crisis – and intensive discussions—at the Swiss Central Bank, February 9, 2010. As regards China this paper also has benefitted from discussions with the Wuppertal research team of the international Sincere project co-financed by the German DFG (chair of Professor Welfens). The usual disclaimer applies.

APPENDIX 1

APPENDIX 1

1.1 APPENDIX 2: Time to Fight the Risk of Deflation in the Euro Area

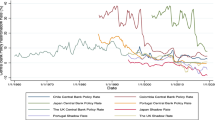

In 2014, it has become obvious that there is a deflation problem in the euro area – with the possible exception of Germany (at least in the short-term). Headline inflation and core inflation have been falling in the euro area since 2011, namely, based on the harmonized consumer price index. There is no doubt that the crisis countries of Greece, Cyprus and Portugal are facing deflation in 2014, namely, falling consumer prices and declining GDP deflator figures. Ireland’s temporary deflation certainly was part of a successful adjustment process, namely, improving the price competitiveness of Ireland’s tradable goods sector. Producer prices are falling in several EU countries and prospects for an economic upswing in 2014/2015 could raise producer prices and consumer prices in the medium term, respectively. However, the risk of deflation cannot be assessed without a closer look at expectations (information on expectations in the market can be taken from inflation hedge swaps; looking at index-link bonds might be rather misleading as the Euro crisis implies that such bonds might be less liquid than non-indexed bonds). The ECB’s forecast for 2015 – as of September 2014 – is only 1.1%.

Inflation expectations – based on ECB surveys of professional forecasters – have been falling in 2014 and expectations were above the actual inflation rate for several quarters so that one may expect anticipated inflation rates to correct for this transitory bias and to fall further over time. The euro area faces a standard monetary policy problem in the sense that the inflation rate for Germany should be higher than for Greece or Portugal. Both need a fall of the relative national price level to regain competitiveness vis-à-vis Germany and other euro countries (with 18 euro countries altogether). However, a similar argument could be made with respect to the US and the monetary policy of the US Federal Reserve System, which also employs a ‘one size fits all’ model for as many as 50 states. The ECB has reduced its central bank interest rate from 0.15% to 0.05% on September 4, 2014; at the same time the ECB declared it would buy asset-based securities - typically representing bundles of loans that banks have given to firms – and covered bonds.

Is this adequate to fight deflationary pressure? It will not suffice to quickly fight deflation unless the ECB declares what standard amount it will buy per quarter, as inflation/deflation expectations cannot be influenced in a decisive way if the ECB’s policy is vague. Given the rather limited amount of ABS and covered bonds available in the euro area, the ECB should encourage banks to create new ABS that will qualify for the ECB program if the respective bank itself holds at least 50% of the ABS until maturity – no other condition can easily put pressure on banks to do a careful job when allocating loans to firms and then bundling these loans in ABS (thus the type of inadequate ABS creation by banks observed in the US in 1998–2007 could be avoided and thus a strong risk exposure of the ECB is also very unlikely). Regional banks – which play a strong role in Germany, Italy and some other euro countries - should be encouraged to create risk-reducing, adequate cross-regional ABS through joint ABS creation with other regional banks, so that no dangerous regional risk enhancement will be embodied in ABS; this requirement also helps to create a level playing field (read: avoids favoring big national banks) and to develop the euro area’s capital markets which are much smaller than those in the US. A second question of the ECB monetary policy is the problem of “one size fits all” - is this an adequate monetary policy for the euro area and its member countries, respectively?

New empirical research from Dominic Quint (2014) has shown that after a difficult starting period of the euro area, the euro member countries did not face more monetary stress – defined by the difference between an optimal national policy and the ECB policy – than states in the US facing a one size fits all policy of the Federal Reserve Bank. It was only during the euro crisis of 2010–2013 that monetary stress increased again in the euro area but it was still much lower than at the start of the euro area. The basic difference between the US and the euro area lies in the field of fiscal policy: the IMF’s analysis has shown that a 1% output shock in the euro area will cause a reduction of the consumption-GDP ratio that is three times as large as in the case of an identical shock in the US; the degree of policy coordination in the euro area is quite weak compared to the US where federal fiscal counter-cyclical policy and automatic stabilizers work better than in the euro area.

A major problem in the euro area is that government expenditures at the supranational level is about 1% of GDP, while in the US the government expenditures of the federal level stand for about 11% of GDP (2012) plus another 9% for social security expenditures at the federal level. In the present setting the supranational policy layer cannot be a strong actor in fiscal policy in the EU.

In a new DSGE modeling paper, researchers from Deutsche Bundesbank – Stähler et al. (2014) – have shown that the fiscal policy multiplier in the euro area is higher for the case of infrastructure expenditure than for the case of government consumption. Thus supply-side fiscal policy can work. Thus there probably is at least one new consensus, namely, that fiscal policy works and that the higher its multiplier is, the stronger the focus of expansionary policy is on public investment. One may find it, however, rather surprising that the authors cannot identify international multiplier effects from public investment. Such multiplier effects may indeed be expected if such investment would mainly focus on investment in highways, railway networks and broadband infrastructure, since in an open economy perspective even infrastructure investment that reduces transportation costs between point A and B within country 1 will automatically reduce transportation costs between point A* and B, so that trade between both countries will be enhanced through such investment. This at least is the logic of the trade gravity equation, and Jungmittag and Welfens (2009) have presented evidence for EU countries that, for example, a rise of international telecommunications volume between countries i and j will raise trade between i and j – more international calls will be made if through more infrastructure investment and more competition, prices of international telecommunications are falling. More trade can bring about specialization gains and impulses for more innovation; innovation dynamics in EU countries in turn benefit from higher internet density and broadband density in these countries and the US (Welfens and Irawan, 2014). More public investment could also make a country more attractive for higher foreign direct investment inflows which normally not only bring a rise of the capital stock and capital intensity, respectively; it should also bring international technology transfer effects so that the marginal product of capital is raised and this in turn will stimulate investment. One should, however, note that empirical evidence from a study looking at EU single market dynamics in the context of time series analysis of innovation dynamics of Germany and the UK has pointed out that technology transfer effects in the UK could not be observed in the case of FDI inflows into the banking sector; only in the case of FDI into the manufacturing sector were such spillovers significant (Barrel and Pain 1997).

The conclusion drawn here is that a distinct euro area fiscal policy should focus mainly on infrastructure expenditures, namely, within a new concept that would allocate new competences to Brussels – the euro area supranational level – and government expenditures that should reach about 6% of GDP: roughly 2% for infrastructure expenditures, 2% for defense expenditures, 0.5% for supranational R&D project support, about 1% for traditional supranational expenditures plus 0.5% for projects on mobile life-long learning in the euro area (or in the EU if other EU countries also want to participate). Add another 0.5% of GDP for covering the first six month of unemployment insurance in all euro area countries and one has the necessary minimum for an efficient and effective fiscal policy in the euro area. This increasing of fiscal power in Brussels is not necessarily in contradiction with the principle of subsidiarity if the latter is – rightly so – interpreted in a dynamic perspective: With more fiscal power in Brussels and exclusive responsibility for counter-cyclical policy in the long run, the voters in EU countries will understand clearly the particular role and responsibility of the supranational policy layer and this in turn should strongly increase voter turnout at European elections (so far it is quite unclear to voters for which policy fields the EU really stands) at least in the euro area countries; and with a higher voter participation in supranational elections, political competition will be reinforced so that the optimum supranational government size will have increased. National parliaments and government of euro area countries could create the basis for a virtual fiscal union in Brussels until steps towards a political union have been taken; more formal coordination is needed in infrastructure policy where the European Commission so far has put emphasis on transnational networks (i.e. railways, pipelines, highways).

With a supranational counter-cyclical fiscal policy there should be a move towards euro bonds and the option for the supranational policy layer to adopt structural deficits of 0.5% of GDP while a special supranational income tax should generate a revenue of 6% of GDP. National income taxes would reduce correspondingly and if this is an optimum vertical government structure – in line with the theory of fiscal federalism – the net efficiency gain should easily be 0.5-1% of GDP and the aggregate income tax ratio could be reduced by that amount so that there is a win-win situation for all countries in the euro area. The structural deficits of member countries should be limited to 0.25% of GDP, which implies – together with a deficit-GDP ratio of 0.5% at the supranational level - in a context of a trend output growth rate of 1.5% a long run debt-GDP ratio of 0.5%. A debt-GDP ratio of 50% should be low enough to make sure that euro bonds will enjoy AAA rating and this in turn is a basis for the euro to maintain its role as an international reserve currency.

Such a position can only be achieved on the basis of being a big trading partner, having a world class banking system, maintaining a low inflation rate and enjoying a top government bond rating. The economic benefit amounts – as shown by this author – to about 0.5% of GDP if one assumes that the difference between the yield on euro bonds held by foreign central banks is 2–3 percentage points lower than the world yield on capital (say 1% compared to 3.5%); if the ratio of global reserves held in euro to the euro area GDP would be 50%, the euro area could effectively run an eternal current account deficit-GDP of 1.25%, if it is rather 20% (as in 2013) the net import-GDP ratio that is obtained for free by the euro area is 0. 5%.

As regards individual euro countries, fiscal devaluation could play a role for adjustment and higher net exports of goods and services: Such a fiscal devaluation means to reduce social security contributions – mostly on the payments of employers – so that marginal costs and prices will fall and international price competitiveness is improved; at the same time the value-added tax rate should be raised in a way that one has a revenue-neutral arrangement. The rise of the VAT rate will also stimulate exports and output. A rising output will in the end translate into higher wages which in turn will be a brake for net exports of goods and services. If the euro area enters deflation in 2015, this will contribute to dampening the inflation in other OECD countries as well and it could indeed undermine the economic upswing in some OECD partner countries. This, in turn, would have a negative repercussion effect on the output development of the euro area. One should not underestimate that the euro area is a large economy, roughly four times the size of the German economy. With inflationary expectations strongly decreasing in 2015, nominal interest rates will continue to fall. The ECB will have to adopt broader quantitative easing and it would be adequate to adopt a modeling approach that includes foreign direct investment in the analysis (Welfens 2011b). Deflation as a policy issue in the whole of Europe could become a serious challenge.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Welfens, P.J.J. Issues of modern macroeconomics: new post-crisis perspectives on the world economy. Int Econ Econ Policy 11, 481–527 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-014-0299-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-014-0299-2