Abstract

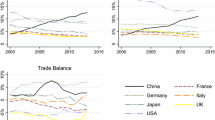

Trade elasticities play a crucial role in translating economic analysis of external adjustment issues into macroeconomic policy. Trade demand elasticities allow policy makers to draw important conclusions about exchange rate misalignments or trade balance changes. This paper endeavors to bring transition countries, namely those from Central and Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States, into the universe of estimated price and activity elasticities of trade volumes. The estimated results imply that the traditional ‘Marshall-Lerner’ condition is not satisfied for transition countries. The estimated price elasticities of export and import demands perform fairly well in predicting out-of-sample changes in trade balance ratios for a broad set of transition countries. In the long run, however, exports and imports are mainly driven by income changes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The CEE country group consists of Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovak Republic, and Slovenia.

CIS is comprised of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan.

Krugman (1989) also observed this phenomenon for other high-growth countries and called it the ‘45-degree rule’.

We choose 2008 as the end date, as the global financial crisis resulted in a great trade collapse with trade flows declining by substantially more than what would be expected from the decline in the world output under normal circumstances. See International Monetary Fund (2010).

The choice of the implemented tests was based on the results from a large scale simulation study conducted by Hlouskova and Wagner (2006), in which various panel unit root tests designed for cross-sectionally independent panels were examined with regard to their performance as a function of the time and cross-section dimensions.

Test results for variables entering the import demand equation are available upon request.

Test results for variables entering the export demand equation are available upon request.

To obtain such a statistical comparison we interact the estimated model for the whole sample with a group dummy variable for CIS countries and test whether estimates of the corresponding dummy variables (deviations of import elasticities between CIS and CEE countries) are significantly different from zero. The t-statistics and probability values are available upon request.

To obtain such a statistical comparison we interact the estimated model for the whole sample with a group dummy variable for CIS countries, as in the case of the GMM System estimator, and test whether estimates of the corresponding dummy variables (difference of import demand elasticities between CIS and CEE countries) are significantly different from zero. The t-statistics and probability values are available upon request.

Source: UNCTAD’s (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development) statistical database on http://uncstadstat.unctad.org and author’s own calculations.

The t-statistic and probability values for estimated export demand elasticities are available upon request.

Ideally, the export demand equation would be estimated on the data for non-commodity exports. This data is, however, not available for both groups of countries.

The estimation results are not shown here but can be provided by the author upon request.

All estimation results and codes can be provided by the author upon request.

The calculated Hausman statistic (χ 2(2) distributed) for MG-PMG is 0.66, for MG-DFE 0.00, and for PMG-DFE 0.18.

The calculated Hausman statistic (χ 2(2) distributed) for MG-PMG is 0.05, for MG-DFE 0.00, and for PMG-DFE 0.01.

The t-statistics and probability values for (differences in) estimated elasticities are available upon request.

Due to insignificant REER elasticities of non-oil exports, estimation result are not reported here but can be provided by the author upon request.

From the view of economic theory, ε X is expected to be negative, as export volumes tend to decrease in case of a real exchange rate appreciation, and ε M is expected to be positive. The condition for an improvement in the trade balance can then be written as |ε X | + ε M > 1, which represents the traditional ‘Marshall-Lerner’ condition. In our study, however, ε X is estimated to be positive, such that we use the expression ε M − ε X > 1.

Note that the satisfaction of the ‘Marshall-Lerner’ condition for single countries does not automatically imply the existence of the so-called ‘S-Curve’, as Bahmani-Oskooee et al. (2008) find evidence for the ‘S-Curve’ for Bulgaria and Croatia, but not for Russia. Bahmani-Oskooee and Kutan (2009) use monthly data for an earlier sample. Due to the lack of monthly or quarterly national accounts data for many countries included in the present paper, we prefer to apply dynamic panel estimation techniques to circumvent small sample handicaps.

We take into consideration only statistically significant whole-sample estimates in the short-run, as separate estimates for the two groups of transition countries are either not statistically significant or do not significantly differ from each other. Hence, the estimates from the GMM model are used for elasticities of imports, and those from the DFE model for elasticities of exports.

Single figures for obtained mean squared deviations can be provided by the author upon request.

In Georgia and Russia, however, the model with only REER changes has somewhat less predictive power, see Table 8.

References

Arellano M, Bond S (1991) Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Rev Econ Stud 58(2):277–297

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Harvey H, W. HS (2013a) Empirical tests of the Marshall-Lerner condition: a literature review. J Econ Stud 40(3):411–443

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Huseynov S, Jamilov R (2013b) Is there a J-curve for Azerbaijan? New evidence from industry-level analysis. Macroeconomics and finance in emerging market economies, forthcoming

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Kara O (2005) Income and price elasticities of trade: some new estimates. Int Trade J 19(2):165–178

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Kutan AM (2009) The J-curve in the emerging economies of Eastern Europe. Appl Econ 41(20):2523–2532

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Kutan AM, Ratha A (2008) The S-curve in emerging markets. Comp Econ Stud 50:341–351

Blundell R, Bond S (1998) Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. J Econ 87:115–143

Goldstein M, Khan MS (1981) Income and price effects in foreign trade. In: Jones R W, Kenen P B (eds) Handbook of international economics, vol II. Elsevier Science Publishers B. V., pp 1041–1105

Hacker RS, Hatemi-J A (2004) The effect of exchange rate changes on trade balances in the short and long run: evidence from German trade with transitional Central European economies. Econ Transit 12(4):777–799

Hakura DS, Billmeier A (2008) Trade elasticities in the Middle East and Central Asia: what is the role of oil? IMF working paper no. 08/216

Harris RDF, Tzavalis E (1999) Inference for unit roots in dynamic panels where the time dimension is fixed. J Econ 91:201–226

Hausman JA (1978) Specification tests in econometrics. Econometrica 46(6):1251–1271

Hlouskova J, Wagner M (2006) The performance of panel unit root and stationarity tests: results from a large scale simulation study. Econ Rev 25(1):85–116

Hooper P, Johnson K, Marquez J (2000) Trade elasticities for G-7 countries. Princeton Studies in International Economies, (87)

Houthakker HS, Magee SP (1969) Income and price elasticities in world trade. Rev Econ Stat 51(2):111–125

International Monetary Fund (2006a) Exchange rates and trade balance adjustment in emerging market economies

International Monetary Fund (2006b) Methodology for CGER exchange rate assessments

International Monetary Fund (2010) World economic outlook, October, Chapter 4.

Kaminski B, Wang ZK, Winters LA, Sapir A, Székely IP (1996) Export performance in transition economies. Econ Pol 11(23):421–442

Krugman P (1989) Differences in income elasticities and trends in real exchange rates. Eur Econ Rev 33:1031–1054

Levin A, Lin C, Chu CJ (2002) Unit root tests in panel data: asymptotic and finite-sample properties. J Econ 108:1–24

Maddala GS, Wu S (1999) A comparative study of unit root tests with panel data and a new simple test. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 61(S1):631–652

Pesaran MH, Shin Y, Smith RP (1999) Pooled mean group estimation of dynamic heterogenous panels. J Am Stat Assoc 94(446):621–634

Pesaran MH, Smith R (1995) Estimating long-run relationships from dynamic heterogenous panels. J Econ 68:79–113

Senhadji A (1998) Time-series estimation of structural import demand equations: a cross-country analysis. IMF Staff Pap 45(2):236–268

Senhadji A, Montenegro C (1999) Time-series analysis of export demand equations: a cross-country analysis. IMF Staff Pap 46(3):259–273

Stuc̆ka T (2003) The impact of exchange rate changes on the trade balance in Croatia. Croatian National Bank Working Paper No. 11

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Zeno Enders, Aasim Husain, Nicole Laframboise, and participants at the seminar of the Middle East and Central Asia Department at the IMF for helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The views expressed herein are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Bundesbank or the IMF, its Executive Board, or its management.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Data description

Import volume: value of imports of goods and services (denominated in US Dollar) deflated by price deflator for imports of goods and services (2000=100) and converted into national currency at the average market bilateral exchange rate to US Dollar in 2000.

Real domestic demand: GDP at constant prices (2000) expressed in national currency or GDP at current prices expressed in national currency deflated by GDP deflator (2000=100) less net exports (exports-imports, see data description for import and export volumes) expressed in national currency at 2000 prices.Real effective exchange rate: trade-weighted real exchange rate deflated by consumer price index (CPI), 2000=100, average total trade weights for 1999-2001, source: IMF Information Notice System.

Export volume: value of exports of goods and services (denominated in US Dollar) deflated by price deflator for exports of goods and services (2000=100) and converted into national currency at the average market bilateral exchange rate to US Dollar in 2000.

Non-oil export volume: in oil exporting countries value of non-oil exports (denominated in US Dollar) with values of exports of services (both denominated in US Dollar) deflated by price deflator for non-oil exports (2000=100) and converted into national currency at the average market bilateral exchange rate to US Dollar in 2000; in other countries total export volume (see data description for export volume).

World real gross domestic product: world real GDP expressed in US Dollar at 2000 prices.

Export-weighted real gross domestic product of main trading partners: GDPs at current prices in national currency deflated by GDP deflator (2000=100) and converted into US Dollar at average market bilateral exchange rate of the 10 most important export partner countries expressed in US Dollar at 2000 prices and weighted by their time-varying shares in exports of the exporting country (see data description for time-varying export shares).

Time-varying export shares: value of merchandise exports to one of the 10 most important export partners expressed in US Dollar relative to total value of merchandise exports to 10 most important export partners, source: IMF Direction of Trade Statistics.

Unless otherwise indicated, all variables are obtained from the IMF World Economic Outlook database.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Buzaushina, A. Trade elasticities in transition countries. Int Econ Econ Policy 12, 309–335 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-014-0273-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-014-0273-z

Keywords

- Income and price elasticities

- Imports

- Exports

- Trade balance adjustment

- Transition economies

- Dynamic panel estimation