Abstract

This paper addresses the relationship between the design of incentives to firms under regulation, mainly the rule for adjusting tariffs, and trade balance performance of the country. We also explore whether this relationship is relevant or not for a typical developing economy like Argentina. We find it is. To study these issues we perform comparative static numerical exercises using a CGE model where service obligation and no entry in regulated industries are assumed. We show that the capital account openness and the rate of exchange regime could be key elements to match with the regulatory regime. The potential inconsistency between the international trade regime and the regulatory regime should not be rejected a priori.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In most cases, reformers have chosen to promote incentives for efficiency in these sectors rather than to guarantee returns through cost-plus regimes. In Latin America, according to a database put together by Guasch (2003), of 954 concessions contracts awarded between the mid-1980s and 2000, 56 % were regulated under a price cap regime and 20 % under the rate-of-return regulation; 24 % of the contracts were hybrids.

It seems rational to expect that the recognition of the presence of a third party (such as the rest of the world) exchanging goods and (capital) services with the regulated party is likely to influence the optimal contract between the regulator and the regulated operator. These optimal contracts are typically modelled on the principal-agent framework in the regulation literature. For an overview, see Laffont and Martimort (2002) or Laffont and Tirole (1993).

To some extent, a rule for determining the tariff can be modelled as a distortion that modifies optimal trade policy (Bhagwati, Panagariya, and Srinivasan 1998 chapter 20). Leaving aside financial and temporal considerations, it is possible that a rate-of-return regulation favors a bigger initial inflow of foreign capital.

We adopt Piggott’s viewpoint “that CGE models are theoretical models with numbers.”

Hoque (1997) discusses international trade theorems when there is factor mobility between countries, but not between sectors; he finds that the international mobility of factors can be seen as a substitute for intersectoral mobility, making valid the Stolper-Samuelson and Rybczynski propositions.See also Jones and Kierzkowski (1986).

A summary of the main characteristics of these models can be found in Bhagwati et al. (1998).

The “small country assumption” in terms of Kehoe and Kehoe (1994).

Considering the information available from National Accounts for Argentina and input–output estimations (INDEC 2001).

The sectors under regulation are transport, telecommunications, electricity distribution, gas distribution, and water distribution. Although these sectors are under different regulatory regimes, we will assume that the aggregated sector is under either a price cap or rate-of-return regulation.

The trade balance must compensate the current account result. Notice that it is not influenced by entrance and exit of capital “in the same period.”

In short, the production function of sector S N , for example, can be written as: \( {q_N}(c_1^I,c_2^I,c_R^I,{Y_N}(L,{K_N})) = \min \left\{ {\frac{{c_1^I}}{{{a_{{1,N}}}}},\frac{{c_2^I}}{{{a_{{2,N}}}}},\frac{{c_R^I}}{{{a_{{R,N}}}}},{L^{\alpha }}K_N^{{1 - \alpha }}} \right\} \), where \( c_i^I \) is the amount of commodity i used as intermediate input.

Dierker et al. (1985) present an analysis of the existence of equilibrium under special pricing rules.

If this assumption were not included, we would need to accept some form of customer rationing (whether of households or firms), making the model much more complicated and inconclusive.

Remember that in the real world, the cost of capital is what drives the decision of investors to enter the country or not. When risk levels are high, one way of reducing this cost of capital and avoiding a binding participation constraint on potential investors in the sector is to grant some temporary degree of protection by either restricting entry or guaranteeing a rate of return to the operator, either implicitly (price cap) or explicitly (cost plus).

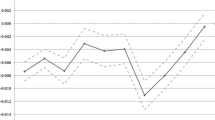

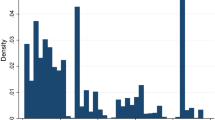

The welfare changes are computed in terms of the equivalent variation as a percentage of household income.

The “competitive” regime is virtual, since the regulated industry might exhibit the characteristics of a natural monopoly.

They become implicit shareholders who have to cover the increase in wage rates that benefits only domestic agents.

Simulations of an efficiency loss of the same magnitude gave similar results but with the opposite sign.

Owners of the firm, however, will not necessarily have incentives to introduce efficiency gains.

References

Bhagwati J, Panagariya A, Srinivasan T (1998) Lectures on International Trade, 2nd edn. MIT Press, Cambridge

Chisari O, Quesada L (2003) Trade Balance Constraints and Optimal Regulation. Centro de Estudios Económicos de la Regulación. Universidad Argentina de la Empresa, Buenos Aires

Chisari O, Estache A, Romero C (1999) Winners and losers of privatization and regulation of utilities: lesson from a general equilibrium model of Argentina. World Bank Econ Rev 13:357–378

Dierker E, Guesnerie R, Neuefeind W (1985) General equilibrium when some firms follow special pricing rules. Econometrica 53:1369–1393

Ginsburgh V, Keyzer M (1997) The Structure of Applied General Equilibrium Models. MIT Press, Cambridge

Guasch J (2003) Concessions: Bust or Boom? An Empirical Analysis of Ten Years of Experience in Concessions in Latin America and Caribbean. World Bank Institute, Washington, DC

Hoque A (1997) Effects of tariffs and factor endowments on income distribution and output composition. Economic Notes 3:549–566

INDEC (2001) Matriz insumo Producto Argentina 1997. Ministerio de Economía, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Jones R, Kierzkowski H (1986) Neighbourhood production structures with an application to international trade. Oxf Econ Pap 38:59–76

Kehoe P, Kehoe T (1994) A primer on static applied general equilibrium models. Federal Reserve of Minneapolis Quarterly Review 18:1

Laffont J, Martimort D (2002) The Theory of Incentives: The Principal-Agent Model. Princeton University Press, Princeton (NJ)

Laffont J, Tirole J (1993) A Theory of Incentives in Procurement and Regulation. MIT Press, Cambridge

Navajas F (2000) El impacto distributivo de los cambios en los precios relativos en la Argentina entre 1988–1998 y los efectos de las privatizaciones y la desregulación económica. in Fundación de Investigaciones Económicas Latinoamericanas. La Distribución del Ingreso en la Argentina. Buenos Aires: FIEL

Shoven J, Whalley J (1973) General equilibrium with taxes: a computational procedure and an existence proof. Rev Econ Stud 40:475–489

Ugaz C, Waddams-Price C (eds) (2003) Utility Privatization and Regulation. Elgar, Manchester

Van Bergeijk P, Haffner R (1996) Privatization, Deregulation and the Macroeconomy: Measuring, Modeling and Policy. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Acknowledgements

A first version was presented at the meeting of the Asociación Argentina de Economía Política. We thank Lucía Quesada and Enrique Neder, and anonymous referees for their constructive comments.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chisari, O.O., Estache, A., Lambardi, G.D. et al. The trade balance effects of infrastructure services regulation. Int Econ Econ Policy 10, 183–200 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-011-0200-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-011-0200-5