Abstract

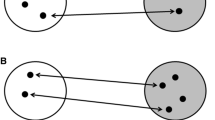

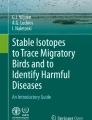

This paper is concerned mainly with the differences between obligate and facultative migration in birds. Obligate migration is considered “hard-wired”, in that the bird seems pre-programmed to leave its breeding area at a certain time each year, and to return at another time. Timing, directions and distances are relatively constant from year to year. This type of migration is thus characterised by its regularity, consistency and predictability. It is found in both short-distance and long-distance migrants, but mainly in the latter. In contrast, facultative migration is considered optional, occurring in response to conditions at the time. Individuals may migrate in some years but not in others, depending on the prevailing food supplies or weather conditions. The timing of autumn migration, and the distance travelled, can be highly variable between individuals and, at the population level, between years. Facultative migration is typical of many partial migrants, but is found in its most extreme form in so-called irruptive migrants. While individual obligate migrants typically return to the same breeding localities year after year, and sometimes also to the same wintering localities, individual irruptive migrants typically breed or winter in widely separated areas in different years, wherever conditions are favourable. It is suggested that these two types of migration are best considered not as distinct, but as lying at opposite ends of a continuum of variation in bird migratory behaviour. Both systems are adaptive; one to conditions in which resource levels vary regularly and predictably in space and time, and the other to conditions in which resource levels vary unpredictably. Suggestions are made for experimental work on captive irruptive species.

Zusammenfassung

Obligater und fakultativer Vogelzug: ökologische Aspekte

Dieser Artikel befasst sich hauptsächlich mit den Unterschieden zwischen obligatem und fakultativem Vogelzug. Obligater Zug wird als “festverankert” erachtet, da Vögel in diesem Fall ihr Brutgebiet jedes Jahr zu einer bestimmten, offensichtlich vorprogrammierten Zeit verlassen und wiederbesiedeln. Zeitablauf, Zugrichtungen und Zugstrecken sind relativ konstant zwischen verschiedenen Jahren. Diese Art von Zug zeichnet sich demnach aus durch Regelmäßigkeit, Konsistenz und Vorhersagbarkeit und kommt bei Kurzstreckenziehern, vor allem aber bei Langstreckenziehern vor. Im Gegensatz dazu wird fakultativer Vogelzug als optional und als Reaktion auf aktuelle Bedingungen betrachtet. So können Individuen in einigen Jahren ziehen, in anderen aber nicht, je nach Nahrungssituation und Wetter. Der Zeitablauf des Herbstzuges und seine Streckenlänge kann zwischen Individuen und auf Populationsebene von Jahr zu Jahr stark variieren. Fakultativer Zug ist für viele Teilzieher typisch und findet seine extremste Form bei sogenannten irruptiven Arten. Während individuelle obligate Zieher typischerweise alljährlich zu denselben Brutgebieten und manchmal auch zu den selben Wintergebieten zurückkehren, brüten oder überwintern individuelle fakultative Zieher in verschiedenen Jahren je nach günstigen Bedingungen häufig in weit voneinander entfernten Gebieten. Jedoch sollten diese beiden Typen von Vogelzug am besten nicht als grundsätzlich verschieden erachtet werden, sondern als Extreme entlang eines Kontinuums von Zugverhalten. Beide Zugtypen sind adaptiv, der eine unter Bedingungen, in denen Ressourcen regelmäßig und vorhersagbar über Raum und Zeit variieren, und der andere unter Bedingungen, in denen Ressourcen unvorhersagbar variieren. Der Artikel schließt mit Vorschlägen zu experimentellen Laborstudien an irruptiven Arten.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The total minutes of migratory restlessness is a function of the number of nights with activity and the mean number of minutes per night.

References

Baumgartner FM, Baumgartner AM (1992) Oklahoma bird life. Oklahoma University Press, Norman

Bensch S, Hasselquist D (1991) Territory infidelity in the polygynous great reed warbler Acrocephalus arundinaceus: the effect of variation in territory attractiveness. J Anim Ecol 60:857–871

Berthold P (2001) Bird migration: a general survey, 2nd edn. Oxford, Oxford University Press

Berthold P, Helbig AJ (1992) The genetics of bird migration: stimulus, timing and direction. Ibis 134:35–40

Berthold P, Bosch W, van den Jakubiec Z, Kaatz C, Kaatz M, Querner U (2002) Long-term satellite tracking sheds light on variable migration strategies of White Storks (Ciconia ciconia). J Ornithol 143:489–495

Berthold P, Kaatz M, Querner U (2004) Long-term satellite tracking of white stork (Ciconia ciconia) migration: constancy versus variability. J Orn 145:356–359

Brewer D, Diamond A, Woodsworth EJ, Collins BT, Dunn EH (2000) Canadian atlas of bird banding, vol 1. Ottawa, Canadian Wildlife Service

Browne SJ, Mead CJ (2003) Age and sex composition, biometrics, site fidelity and origin of Brambling Fringilla montifringilla wintering in Norfolk, England. Ringing Migr 21:145–153

Burton NHK, Evans PR (1997) Survival and winter site fidelity of Turnstones Arenaria interpres and Purple Sandpipers Calidris maritima in northeast England. Bird Study 44:35–44

Chan K (2005) Partial migration in the silvereye (Aves Zosateropidae): pattern, synthesis and theories. Ethol Ecol Evol 17:349–363

Forero MG, Donázar JA, Blas J, Hiraldo F (1999) Causes and consequences of territory change and breeding dispersal distance in the black kite. Ecology 80:1298–1310

Fuller M, Holt D, Schueck L (2003) Snowy owl movements: variation on a migration theme. In: Berthold P, Gwinner E, Sonnenschein E (eds) Avian migration. Springer, Berlin, pp 359–366

Gauthreaux SA (1982) The ecology and evolution of avian migration systems. In: Farner DS, King JR (eds) Avian biology, vol 6. Academic, New York, pp 93–167

Götmark F (1982) Irruptive breeding of the redpoll, Carduelis flammea, in South Sweden in 1975. Vår Fågelvärld 41:315–322

Gwinner E, Schwabl H, Schwabl-Benzinger I (1988) Effects of food-deprivation on migratory restlessness and diurnal activity in the garden warbler Sylvia borin. Oecologia 77:321–326

Helms CW (1963) The annual cycle and Zugunruhe in birds. Proc Int Orn Cong 13:925–939

Hildén O (1979) Territoriality and site tenacity of Temminck’s Stint Calidris temminckii. Ornis Fenn 56:56–74

Holmes RT, Sherry TW (1992) Site fidelity of migratory warblers in temperate breeding and neotropical wintering areas: applications for population dynamics, habitat selection, and conservation. In: Hagan JM, Johnston DW III (eds) Ecology, conservation of neotropical migrant landbirds. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC, pp 563–575

Lack D (1954) The natural regulation of animal numbers. Oxford, University Press

Lawn MR (1982) Pairing systems and site tenacity of the willow warbler Phylloscopus trochilus in Southern England. Ornis Scand 13:193–199

Lindström Å, Enemar A, Andersson G, von Proschwitz T, Nyholm NEI (2005) Density-independent reproductive output in relation to a drastically varying food supply: getting the density measure right. Oikos 110:155–163

Mikkonen AV (1983) Breeding site tenacity of the Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs and the Brambling F. montifringilla in northern Finland. Ornis Scand 14:36–47

Newton I (2006a) Advances in the study of irruptive migration. Ardea 94:432–460

Newton I (2006b) Movement patterns of common crossbills Loxia curvirostra in Europe. Ibis 148:782–788

Newton I (2008) The ecology of bird migration. Academic, London

Nisbet ICT, Medway L (1972) Dispersion, population ecology and migration of Eastern Great Reed Warblers Acrocephalus orientalis wintering in Malaysia. Ibis 114:451–494

Payevsky VA (1994) Age and sex structure, mortality and spatial winter distribution of Siskins (Carduelis spinus) migrating through eastern Baltic area. Die Vogelwarte 37:190–198

Peiponen VA (1967) Südliche Fortpflanzung und Zug von Carduelis flammea (L.) in Jahre 1965. Ann Zool Fenn 4:547–549

Pulido F (2012) Evolutionary genetics of partial migration in birds—the threshold model of migration revisited. Oikos (in press)

Pulido F, Berthold P (2003) Quantitative genetic analyses of migratory behaviour. In: Berthold P, Gwinner E, Sonneschein E (eds) Avian migration. Springer, Berlin, pp 53–77

Putnam LS (1949) The life history of the cedar waxwing. Wilson Bull 61:141–182

Ramenofsky M, Cornelius J, Helm B (2011) Physiological and behavioural responses of migrants to environmental cues. J Orn (in press)

Reynolds RT, Linkhart BD (1987) Fidelity to territory and mate in Flammulated Owls. In: Nero RW, Clark RJ, Knapton RJ, Hamre RH (eds) Biology, conservation of northern forest owls. Rocky Mountain Forest & Range Experimental Station, Fort Collins, pp 234–238

Roff DA (1996) The evolution of threshold traits in animals. Q Rev Biol 71:3–35

Shaw G (1990) Timing and fidelity of breeding for Siskins Carduelis spinus in Scottish conifer plantations. Bird Study 37:30–35

Smith N (1997) Observations of wintering Snowy Owls (Nyctea scandiaca) at Logan Airport, East Boston, Massachusetts from 1981 to 1997. In: Duncan JR, Johnson DH, Nicholls TH (eds) Biology and Conservation of Owls of the Northern Hemisphere: 2nd Int Symp, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, 5–9 Feb 1997, pp 591–597

Smith HG, Nilsson J-Å (1987) Intraspecific variation in migratory pattern of a partial migrant, the blue tit (Parus caeruleus): an evaluation of different hypotheses. Auk 104:109–115

Smith KW, Reed JM, Trevis BE (1992) Habitat use and site fidelity of green sandpipers Tringa ochropus wintering in southern England. Bird Study 39:155–164

Staicer CA (1992) Social behaviour of the Northern Parula, Cape May Warbler, and Prairie Warbler wintering in second-growth forest in southwestern Puerto Rico. In: Hagan JM, Johnston DW (eds) Ecology, conservation of neotropical migrant landbirds. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC, pp 308–320

Svärdson G (1957) The “invasion” type of bird migration. B Birds 50:314–343

Terrill SB (1987) Social dominance and migratory restlessness in the dark-eyed junco (Junco hyemalis). Behav Ecol Sociobiol 21:1–11

Terrill SB (1990) Ecophysiological aspects of movements by migrants in the wintering quarters. In: Gwinner E (ed) Bird migration. Physiology, ecophysiology. Springer, Berlin, pp 130–143

Terrill SB, Ohmart RD (1984) Facultative extension of fall migration by yellow-rumped warblers (Dendroica coronata). Auk 101:427–438

Troy DM (1983) Recaptures of redpolls: movements of an irruptive species. J Field Ornithol 54:146–151

van Noordwijk AJ, Pulido F, Helm B, Coppack T, Delingat J, Dingle H, Hedenström A, van der Jeugd H, Marchetti C, Nilsson A, Pérez-Tris J (2006) A framework for the study of genetic variation in migratory behaviour. J Ornithol 147:221–233

Wernham CV, Toms MP, Marchant JH, Clark JA, Siriwardena GM, Baillie SR (2002) The migration atlas: movements of the birds of Britain and Ireland. T & AD Poyser, London

Wilson HJ, Norriss DW, Walsh A, Fox AD, Stroud DA (1991) Winter site fidelity in Greenland white-fronted geese Anser albifrons flavirostris: implications for conservation and management. Ardea 79:287–294

Wiltschko W, Wiltschko R (2003) Mechanisms of orientation and navigation in migratory birds. In: Berthold P, Gwinner E, Sonnenschein E (eds) Avian migration. Springer, Berlin, pp 433–456

Yunick RP (1983) Winter site fidelity of some northern finches (Fringillidae). J Field Ornithol 54:254–258

Yunick RP (1997) Geographical distribution of re-encountered Pine Siskins captured in upstate, eastern New York during the 1989–90 irruption. N Amer Bird Bander 22:10–15

Zink G, Bairlein F (1995) Der Zug Europäischer Singvögel. AULA-Verlag, Wiesbaden

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Barbara Helm, Francisco Pulido, Marilyn Ramenofsky and an anonymous referee for helpful comments on this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Cristina Yumi Miyaki.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Newton, I. Obligate and facultative migration in birds: ecological aspects. J Ornithol 153 (Suppl 1), 171–180 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-011-0765-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-011-0765-3