Abstract

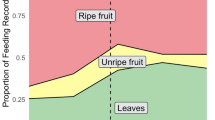

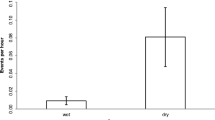

Spider monkeys exhibit a fission–fusion type of social organization. I studied party size and party composition in wild long-haired spider monkeys (Ateles belzebuth belzebuth) in three study periods at La Macarena, Colombia and found that overall party size was larger in the fruit-abundant season. Mean party size in which males were observed was relatively stable across seasons. In contrast, the mean party size of females varied. Females were observed in larger parties in the fruit-abundant season than in the fruit-scarce season. Moreover, whereas males associated with each other at an almost equal frequency across seasons, females associated with each other more frequently in the fruit-abundant season. Females with infants or small juveniles were more often in association with other individuals than were cycling females. The intensity of individual relationships varied according to season, such that even mothers and sons were not always strongly associated. In a large party, females with infants may gain from predation avoidance but they are at a disadvantage in terms of scramble competition. The balance between these factors may change with fruit availability and may influence party size in different periods. For males, party formation may facilitate the defense of resources from neighboring groups more than provide predation avoidance.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Alexander RD (1974) The evolution of social behavior. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 5:325–383

Altmann J (1974) Observational study of behaviour: sampling method. Behaviour 49:227–267

Altmann J (1980) Baboon mother and infants. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.

Boesch C, Boesch-Achermann H (2000) The chimpanzees of the Taï forest. Oxford University Press, New York

Carpenter CR (1933) Report on field studies of the howling monkey, Alouatta palliata inconsonans, and the red spider monkey, Ateles geoffroyi kuhl, with comparisons. Psychol Bull 30:734–735

Carpenter CR (1935) Behavior of red spider monkeys in Panama. J Mammal 16:171–180

Chapman CA (1990) Association patterns of spider monkeys: the influence of ecology and sex on social organization. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 26:409–414

Chapman CA, Wrangham RW, Chapman LJ (1995) Ecological constraints on group size: an analysis of spider monkey and chimpanzee subgroups. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 36:59–70

Chapman CA, Gautier-Hion A, Oates JF, Onderdonk DA (1999) African primate communities: determinants of structure and threats to survival. In Fleagle JG, Janson CH, Reed KE (eds) Primate communities. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 1–38

Clutton-Brock TH, Harvey PH (1977) Primate ecology and social organization. J Zool 183:1–39

Crook JH (1972) Sexual selection, dimorphism, and social organization in the primates. In: Cambell BG (ed) Sexual selection and the descent of man. Aldine, Chicago, pp 231–281

Eisenberg JF (1973) Reproduction in two species of spider monkeys, Ateles fusciceps and Ateles geoffroyi. J Mammal 54:955–957

Hernandez Lopez L, Mayagoitia L, Esquivel Lacroix C, Rojas Maya S, Mondragon Ceballos R (1998) The menstrual cycle of the spider monkey (Ateles geoffroyi). Am J Primatol 44:183–195

Inaba A, Izawa K (2000) Ecological and sociological studies in wild spider monkeys MB-1 group at La Macarena, Colombia (in Japanese). In: Izawa K (ed) Adaptive significance of fission-fusion society in Ateles. Miyagi University of Education, Sendai, pp 21–36

Izawa K (1998) Zoku kumozaru mo mureru—Rigou shusan shakai no sotogawa [Even spider monkeys do aggregate II. Outer side of fission-fusion social organization] (in Japanese). Monkey 42:3–14

Izawa K (2000) Two loud call of spider monkeys: mobbing call and long call. In: Izawa K (ed) Adaptive significance of fission-fusion society in Ateles (in Japanese). Miyagi University of Education, Sendai, pp 125–141

Izawa K, Mizuno A (1977) Palm-fruit cracking behavior of wild black-capped capuchin (Cebus apella). Primates 18:773–792

Janson CH (1988) Food competition in Brown capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella): quantitative effects of group size and tree productivity. Behaviour 105:53–76

Kano T (1982) The social group of pygmy chimpanzees (Pan paniscus) of Wamba. Primates 23:171–188

Kimura K, Nishimura A, Izawa K, Mejia CA (1994) Annual changes of rainfall and temperature in the tropical seasonal forest at La Macarena field station, Colombia. Field Stud New World Monkeys La Macarena Colombia 9:1–3

Klein LL (1972) The ecology and social organization of the spider monkey, Ateles belzebuth. PhD thesis, University of California, Berkley

Klein LL, Klein DB (1977) Feeding behaviour of the Colombian spider monkey. In: Clutton-Brock TH (ed) Primate ecology. Academic Press, London, pp 153–181

Matsushita K, Nishimura A (2000) Ecological and sociological studies in wild spider monkeys MB-3 group at La Macarena, Colombia. In: Izawa K (ed) Adaptive significance of fission-fusion society in Ateles (in Japanese). Miyagi University of Education, Sendai, pp 57–76

Nishida T (1968) The social group of wild chimpanzees in the Mahale Mountains. Primates 9:167–224

Roosmalen MGMV (1980) Habitat, preferences, diet, feeding strategy, and social organization of the black spider monkey (Ateles paniscus paniscus) in Surinam. PhD thesis, University of Wageningen, The Netherlands

Schaik CP van (1983) Why are diurnal primates living in groups? Behaviour 87:120–144

Shimooka Y (2000) Ecological and sociological studies in wild spider monkeys MB-2 group at La Macarena, Colombia (in Japanese). In: Izawa K (ed) Adaptive significance of fission-fusion society in Ateles. Miyagi University of Education, Sendai, pp 37–55

Sokal RR, Rohlf FJ (1995) Biometry. Freeman, New York

Stevenson PR (2002) Frugivory and seed dispersal by wooly monkeys at Tinigua National Park, Colombia. PhD thesis, State University of New York, Stony Brook

Stevenson PR, Quinones MJ, Ahumada JA (2000) Influence of fruit availability on ecological overlap among four neotropical primates at Tinigua National Park, Colombia. Biotropica 32:533–544

Strier KB (1986) The behavior and ecology of the wooly spider monkey, or Muriqui (Brachiteles arachnoides E. Geoffroyi 1806). Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

Symington MM (1987) Ecological and social correlates of party size in the black spider monkeys, Ateles paniscus chamek. PhD thesis, Princeton University, Princeton, N.J.

Symington MM (1988) Food competition and foraging party size in the black spider monkey (Ateles paniscus chamek). Behaviour 105:117–134

Symington MM (1990) Fission-fusion social organization in Ateles and Pan. Int J Primatol 11:47–61

Terborgh J (1983) Five new world primates. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Terborgh J, Janson CH (1986) The socioecology of primate groups. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 17:111–135

Wrangham RW (2000) Why are male chimpanzees more gregarious than mothers? A scramble competition hypothesis. In: Kappeler PM (ed) Primate males. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 248–258

Yamada M (1963) A study of blood-relationship in the natural society of Japanese macaque: an analysis of co-feeding, grooming and playmate relationships in Minoo-B troop. Primates 4:43–65

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the COE program promoted by the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture, JAPAN and by a Grant-in Aid from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture, International Scientific Research (Field Research) No.09041144 as a cooperative research project between Colombia and Japan. I am grateful to the Colombia–Japan primate research project members: Dr. Kosei Izawa, Dr. Carlos Mejia, Dr. Akisato Nishimura, Dr. Koshin Kimura, Ms. Agumi Inaba, Mr. Andres Link, and especially Dr. Pablo Stevenson who provided me with phenological data. Mr. Alvaro Sanabria P. and Mr. Nelson Silva greatly assisted me in the field. I also thank the Ministry of Environment of the Colombian Government for granting permission to undertake the investigation in Macarena-Tinigua National Park. I am grateful to Dr. Hideki Sugiura and two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments and I thank members of the Department of Ecology and Social Behavior and the Field Research Center of the Primate Research Institute, Kyoto University as well as members of the Research Group for Tropical Forest Primates for ever-fruitful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Shimooka, Y. Seasonal variation in association patterns of wild spider monkeys (Ateles belzebuth belzebuth) at La Macarena, Colombia. Primates 44, 83–90 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-002-0028-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-002-0028-2