Abstract

We build a pricing-to-market (PTM) model with firm heterogeneity, which allows for imperfect competition and market segmentation in the presence of flexible exchange rates, horizontal and vertical differentiation and different tastes of consumers in destination markets. We derive firm’s pricing behaviour in response to price and quality competition shocks. We show that there is PTM heterogeneity across firms if quality has a role. We empirically assess the main predictions of our theoretical framework on Italian firm-level data. We document that export-domestic price margins are significantly affected by price and quality competitiveness factors even controlling for foreign demand conditions, size, export intensity, destination markets and unobservables. Finally, we provide evidence of strong heterogeneity across firms in their reaction to price and quality competitiveness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Empirical literature provides evidence that preferences for quality vary across countries, e.g. Hummels and Klenow (2005) and Choi et al. (2009). Crinò and Epifani (2008) explicitely link taste for quality to per-capita income to study the relationship between productivity, quality and export intensity.

By the same token, having \( z_{j} > 1 \), is not sufficient for quality to affect utility; it is necessary that consumers appreciate quality, \( \delta_{l} > 0 \), so that both terms co-determine consumers’ valuation of firm j’s product.

In (1) \( \bar{P}_{l}^{'} = \int_{{j^{'} \in \Upomega }} {{{p_{{c,l,j^{'} }} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{p_{{c,l,j^{'} }} } {z_{{j^{'} }}^{{\delta_{l} }} }}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {z_{{j^{'} }}^{{\delta_{l} }} }}dj^{'} } \), where\( p_{{c,l,j^{'} }} \) is the price of variety \( j^{'} \ne j \) made by competitors in l. Note that in (1) the higher is quality, the higher is quantity demanded since \( \frac{{\partial q_{{_{l,j} }}^{dem} }}{{\partial z_{j} }} = \frac{{\delta_{l} L_{l} }}{{\gamma_{l} z_{j}^{{2\delta_{l} }} }}\left( {2\frac{{p_{o,l,j} E_{o,l} \tau_{o,l} }}{{z_{j}^{{\delta_{l} }} }} - M_{l} } \right) \), where the term in parentheses is positive since from (3) \( 2\frac{{p_{o,l,j} E_{o,l} \tau_{o,l} }}{{z_{j}^{{\delta_{l} }} }} = M_{l} + \frac{{a_{j} }}{{z_{j}^{{\delta_{l} }} }} \).

Profits earned in markets o and l, in terms of currency of country \( o \), are given respectively by \( \pi_{o,o} = \frac{{L_{o} }}{{4\gamma_{o} }}\left( {a_{o,o}^{'} - a_{o,j}^{'} } \right)^{2} \) and \( \pi_{o,l} = \frac{{L_{l} }}{{4\gamma_{l} }}\left( {a_{o,l}^{'} - a_{l,j}^{'} } \right)^{2} \).

Expression (4) comes from setting expected profits of producers located in the two countries and selling in the two markets equal to the entry costs (which are the same for all producers in all markets).

Also a rise in bilateral transport cost can be interpreted as a factor of fiercer competition, since it makes the destination-market cutoff marginal cost more stringent for exporters: higher transport costs amplifyes the competitive disadvantage of exporters with respect to domestic producers. This impact should not be confused with the trade liberalization effect that in (5) works through the term \( (1 + \tau^{ - k} )^{ - 1/(k + 2)} \): a fall of \( \tau \) increases competition in all markets, inducing a reduction of the average price \( \bar{P}_{l} \) (and hence a rise of \( C_{l} \)).

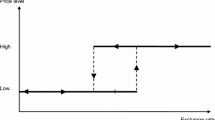

When \( 0 < V_{l} < 1 \), the more negative fob-price response characterising firms with higher a j derives from the fact that relevance of quality causes a reduction of the markup response to price competition, in correspondence of larger a j , which is outweighed by the increase in marginal cost. When \( V_{l} > 1 \), the markup response increases with \( a_{j} \) and this cumulates with the marginal cost rise, magnifying the impact of higher a j on price.

A quality level not too distant from competitors and/or a not too high taste fo quality would allow higher quality (but below-the-average) firms to smooth the negative price response with respect to lower quality ones.

For sake of simplicity we assume in (7) that trade cost variables are time independent. This implies that τ is constant: it gives rise to different price levels in the two markets, but it is not a cause of PTM. Morevoer in (7) \( C_{H} = {1 \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {1 {\bar{P}_{H} }}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {\bar{P}_{H} }} \) as \( E_{H,H} = \tau_{H,H} = 1 \).

Investigating export behaviour of a sample of Italian firms, Crinò and Epifani (2008) find strong support to the positive correlation between productivity and quality of goods.

We consider as exporting firms those sample units which have exported at least once in one or more of the destination markets. Fully exporting firms (that is, firms exporting the whole production) and those with less than 5 employees are not included.

It represents the microdata qualitative counterpart of the real effective exchange rate (REER). Using aggregate quarterly data over the period 1994–2007, the correlation between the ISTAT price competitiveness indicator (pcf) and the cyclical components of the REER from the Bank of International Settlements is statistically significant (see also Basile et al. 2009).

Export intensity can affect firms’ pricing strategies in number ways: first, firms with a low foreign projection are likely to implement ‘hit-and-run’ pricing strategies, maximizing profit margins abroad, disregarding the consequence of a possible exit; second, higher export intensities might reflect a higher notoriety of the firm’s brand abroad and, thus, a greater probability to make the price; third, almost fully export-oriented firms (i.e. firms characterized by a very high ratio between exports and total revenues) could be interested in pursuing pricing strategies mainly focused on defending their market shares abroad. As a consequence, the ultimate effect of export intensity on the response variable is likely to be highly nonlinear.

The introduction of domestic and foreign demand conditions in the model allows us to (partially) control for the perceived business environment faced by exporting firms. In an environment characterized by uncertainty and asymmetric information, indeed, firms cannot observe the actual level of competitiveness of foreign competitors, but they can only formulate conjectures about their relative position in terms of price and non-price (quality) factors. Obviously, these are not unconditional conjectures; rather they are affected by the perceived business environment faced by exporting firms.

The rationale for the inclusion of such a variable comes from the historical weaker export orientation and the bias toward lower-quality goods of Southern regions with respect to the rest of the Italian manufacturing sector.

The permanent-transitory decomposition has an appealing economic interpretation in our context since we are interested in permanent (rather than transitory) effects, particularly in the case of non-price (quality) competitiveness. Indeed, the level effect captures heterogeneous reactions of firms as opposed to shock effects which allows the model to take account of some short-run dynamics.

The probit equation includes as explanatory variables the size of the firm (in terms of log of the number of employees), the square of firm size, the geographical location of the firm and the industrial sector.

All estimates include sectoral, regional, time and destination market controls. Simulated maximum likelihood estimations have been performed by using 50 Halton sequences.

While the information provided by the survey possess the desirable property of being “internally” consistent, it is likely to expect that the variables involved may be “intrinsically” endogenous. In order to tackle this possible source of misspecification of the empirical framework, we consider a time lag between response and time-varying covariates.

Direct evidence of the fact that Italian firms sell abroad, on average, goods of higher quality compared with those sold by their competitors may be found in Lissovolick (2008).

References

Antoniades, A. (2008). Heterogeneous firms, quality and trade. Mimeo: Georgetown University.

Atkeson, A., & Burstein, A. (2008). Pricing-to-market, trade costs and international relative prices. Mimeo: UCLA University.

Auer, R., & Chaney, T. (2008). Cost pass-through in a competitive model of pricing-to-market. (Swiss National Bank Working Papers, 2008-06). Zurich: Swiss National Bank.

Baldwin, R. (1988). Hysteresis in import prices: The beachhead effect. American Economic Review, 78(4), 773–785.

Baldwin, R., & Harrigan, J. (2007). Zeros, quality and space: Trade theory and trade evidence. (NBER Working Paper Series 13214). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Basile, R., de Narids, S., & Girardi, A. (2009). Pricing to market of Italian exporting firms. Applied Economics, 41(12), 1543–1562.

Berman, N., Martin, P., & Mayer, T. (2009). How do different exporters react to exchange rate changes? Theory, empirics and aggregate implications. (CEPR Discussion Paper Series, 7493). London: Centre for Economic Policy Research.

Bernard, B. A., & Jensen, J. B. (1995). Exporters, jobs and wages in US manufacturing: 1976–87. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity: Microeconomics, 67–112.

Bernard, B. A., Eaton, J., Jensen, J. B., & Kortum, S. (2003). Plants and productivity in international trade. American Economic Review, 93(4), 1268–1290.

Betts, C., & Devereux, M. (1996). The exchange rate in a model of pricing to market. European Economic Review, 40(3–5), 1007–1021.

Choi, Y. C., Hummels, D., & Xiang, C. (2009). Explaining import quality: The role of income distribution. Journal of International Economics, 78(2), 293–303.

Corsetti, G., Dedola, L., & Leduc, S. (2005). DSGE models of high exchange rate volatility and low pass-through. (International Finance Discussion Papers 845). Washington, DC: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Crinò, R., & Epifani, P. (2008). Productivity and export intensity to high-income and low-income countries. Mimeo: Bocconi University.

Dornbusch, R. (1987). Exchange rates and prices. American Economic Review, 77(1), 93–106.

Greene, W. H. (2004). Interpreting estimated parameters and measuring individual heterogeneity in random coefficient models. (Working Papers 04-08). New York University, Leonard N. Stern School of Business, Department of Economics.

Hallak, J. C. (2006). Product quality and the direction of trade. Journal of International Economics, 68(1), 238–265.

Hummels, D., & Klenow, P. (2005). The variety and quality of a nation’s exports. American Economic Review, 95(3), 704–723.

Kneller, R., & Yu, Z. (2008). Quality selection, Chinese exports and theories of heterogeneous firm trade. (GEP Discussion Papers 08/44). Nottingham: University of Nottingham.

Krugman, P. R. (1987). Pricing to market when the exchange rate changes. In S. W. Arndt & J. D. Richardson (Eds.), Real financial linkages among open economies. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Lissovolick, B. (2008). Trends in Italy’s non-price competitiveness. (IMF Working Paper 08/124). Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Marston, R. C. (1990). Pricing to market in Japanese manufacturing. Journal of International Economics, 29(3–4), 217–236.

Melitz, M. J., & Ottaviano, G. I. P. (2008). Market size, trade, and productivity. Review of Economic Studies, 75(1), 295–316.

Rodriguez-Lopez, J. A. (2011). Prices and exchange rates: A theory of disconnect. Review of Economic Studies, 78(3), 1135–1177.

Wooldridge, J. (2002). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Acknowledgments

We thank Giuseppe De Arcangelis, Antonella Nocco, Francesco Nucci and two referees for their helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Basile, R., de Nardis, S. & Girardi, A. Pricing to market, firm heterogeneity and the role of quality. Rev World Econ 148, 595–615 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-012-0133-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-012-0133-2