Abstract

This paper presents an experimental approach to compare the performance of alternative business process designs. We use an example case of an electronic group buying setting to demonstrate how our approach can be applied in practice. More specifically, we chose a standard business process, the sales process as implemented on a group buying platform, to illustrate how a business process may be redesigned in order to better meet the needs of customers. For that purpose, we introduce a social technology feature to support cooperation among buyers in the sales process and then analyze the performance impact of the proposed business process redesign. We combine principles from design science and experimental economics to aid the business redesign process. To allow for an experimental evaluation in a controlled laboratory setting, we implement a simplified prototype model and an experimental electronic group-buying platform in the laboratory. We then employ the methods of experimental economics to generate process performance data and evaluate the effectiveness of the new process model design in the lab that can provide valuable insights to platform managers for redesigning the real-world system. We posit that combining the principles of design science and experimental economics offers researchers a useful and cost-effective method to systematically evaluate theoretical predictions about process model design.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Social technology refers to software that connects users and supports user-to-user interactions, and is typically deployed over Internet or mobile platforms.

In a fully developed business application, the experimental platform would likely include a simplified and scaled-down version of the commercial platform software and might use a formal business process language like UML to specify the alternative business process designs that are evaluated. Our prototype model is implemented with the z-tree software.

While it is desirable to base business process redesign proposals on theoretical arguments, our evaluation approach can also be used with purely exploratory rather than theoretically grounded hypotheses.

We use a simple and informal representation of the group-buying business process. In real business settings, it would be preferable to use some formal business process model representation language, such as UML, for example (Russel et al. 2006).

For readers who are interested in a more general overview of related studies on group buying behavior and economics tested in laboratory experiments we refer to Pelaez et al. (2013).

The trading terms (economic performance measures like buyer profit or surplus), bidding rules, and mechanism (double auction) are standard techniques in experimental economics.

Research in experimental economics has shown that the continuous double auction is generally the best performing pricing mechanism in terms of allocative efficiency of resources and also in terms of convergence speed, which is particularly important in laboratory experiments where trading sessions have be very short. For those reasons, double auctions are the default pricing mechanism for market experiments.

Recall that we repeated the experiment ten times over ten experimental rounds in which the WTP parameters were rotated among the buyers. We arbitrarily chose period 10 as the reference period, and used dummy coding to indicate the specific round. For example, period 1 was coded as P1 = 1 and P2, …, P9 = 0.

References

Anand KS, Aron R (2003) Group buying on the web: a comparison of price-discovery mechanisms. Manag Sci 49:15–46

Anderhub V, Engelmann D, Güth W (2002a) An experimental study of the repeated trust game with incomplete information. J Econ Behav Organ 48(2):197–216

Anderhub V, Gächter S, Königstein M (2002b) Efficient contracting and fair play in a simple principal-agent experiment. Exp Econ 5(1):5–27

Chen Y, Ledyard JO (2010) Mechanism design experiments. In: Durlauf SN, Blume LE (eds) Behavioural and experimental economics. Palgrave Macmillan Publishers Ltd., New York, pp 191–206

Chen J, Chen X, Kauffman RJ, Song X (2009) Should we collude? Analyzing the benefits of bidder cooperation in online group-buying auctions. Electron Commer Res Appl 8:191–202

Clemons EK (2008) How information changes consumer behavior and how consumer behavior deter-mines corporate strategy. J Manag Inform Syst 25:13–40

Davenport T (1993) Process innovation: reengineering work through information technology. Harvard Business School Press, Boston

Davenport T, Short J (1990) The new industrial engineering: information technology and business process redesign. Sloan Manag Rev 31:11–27

Dennis AR, Fuller RM, Valacich JS (2008) Media, tasks, and communication processes: a theory of media synchronicity. MIS Q 32:575

Fischbacher U (2007) Z-tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments, experimental economics. Exp Econ 10:171

Galbraith JK (1952) American capitalism—the concept of countervailing power. In: Houghton Mifflin, pp. 217

Granados N, Gupta A, Kauffman RJ (2010) Information transparency in business-to-consumer markets: concepts, framework, and research Agenda. Inform Syst Res 21:207–226

Gregor S, Hevner AR (2013) Positioning and presenting design science research for maximum impact. MIS Q 37(2):337–355

Hammer M, Champy J (1993) Reengineering the corporation: a manifesto for business revolution. Harper Collins, New York

Hevner, Alan R, March ST, Park J, Ram S (2004) Design science in information systems research. MIS Q 28:75–105

Hey JD, Morone A (2004) Do markets drive out lemmings (or vice versa)? Economica 71:637–659

Holthausen R, Verrecchia RE (1990) The effect of informativeness and consensus on price and volume behavior. Account Rev 65:191–208

Jing X, Xie J (2011) Group buying: a new mechanism for selling through social interactions. Manag Sci 57:1354–1372

Ku G, Malhotra D, Murnighan JK (2005) Towards a competitive arousal model of decision-making: a study of auction fever in live and Internet auctions. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 96:89–103

Kuhlthau C (1999) The role of experience in the information search process of an early career information worker: perceptions of uncertainty, complexity, construction, and sources. J Am Soc Inform Sci 50:399–412

Lang KR, Li T (2013–2014) Introduction to the special issue: business value creation enabled by social technology. Int J Electron Commer 18(2):5–10

Liang TP, Turban E (2012) Social commerce: a research framework for social commerce. Int J Electron Commer 16(2):5–13

Lind MR, Zmud RW (1991) Theinfluence of a convergence in understanding between technology providers and users on information technology innovativeness. Organ Sci 2:195–217

Overby E (2008) Process virtualization theory and the impact of information technology. Organ Sci 19:277–291

Peffers K, Tuunainen T, Rothenberger M, Chatterjee S (2008) A design science research methodology for information systems research. J Manag Inform Syst 24(3):45–77

Pelaez A, Lang KR, Yu Y (2013) Social buying: the effects of group size and communication on buyer performance. Int J Electron Commer 18(2):127–157

Rasmusen EB (2006) Strategic implications of uncertainty over one’s own private value in auctions. Adv Theor Econ 6:7

Rha J, Widdows R (2002) The internet and the consumer: countervailing power revisited. Prometh Crit Stud Innov 20:107–118

Rothschild M (1974) Searching for the lowest price when the distribution of price is unknown. J Politi Econ 82:689–711

Ruffle BT (2000) Some factors affecting demand withholding in posted-offer markets. Econ Theor 16:529–544

Rummler GA, Brache AP (1995) Improving performance: how to manage the white space in the organizational chart. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

Russel N, van der Aalst WMP, ter Hostedte AHM, Wohed P (2006) On the suitability of UML 2.0 activity diagrams for business process modeling. In: Proceedings of the 3rd Asia-Pacific Conference on Conceptual Modeling, Australian Computer Society, Darlinghurst, Australia, 53:95–104

Scherer FM, Ross D (1990) Industrial market structure and economic performance. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign's Academy for entrepreneurial leadership historical research reference in entrepreneurship

Simon HA (1972) Theories of bounded rationality. In: McGuire CB, Radner R (eds) Decision and organization. North-Holland, Amsterdam, pp 161–176

Simonsohn U, Ariely D (2008) When rational sellers face non-rational buyers: evidence from herding one Bay. Manag Sci 54:1624–1637

Smith VL (1989) Theory, experiment and economics. J Econ Perspect 3:151–169

Zigurs I, Buckland BK (1998) Atheory of task technology fit and group support systems effectiveness. MIS Q 12:313–334

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

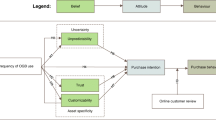

1.1 The experimental software: z-tree

In z-tree a market and the parameters of the market experiment are set up on the central computer, known as the server (left of diagram). The experimenter starts the z-tree software and loads up the file that contains the code and configuration, which will be used by each of the participants that are running z-leaf on computers in the lab. Data is stored on the file system of the z-leaf server as data files, where the experiment is controlled by the experimenter (bottom of diagram). Files are saved in both a proprietary format and excel files for easy import into statistical analysis packages such as SAS, R, STATA, SPSS, etc. A special module of R is available (at http://www.kirchkamp.de) to easily import data from these formats maintaining the structure of the data objects and is available.

In z-tree a market and the parameters of the market experiment are set up on the central computer, known as the server (left of diagram). The experimenter starts the z-tree software and loads up the file that contains the code and configuration, which will be used by each of the participants that are running z-leaf on computers in the lab. Data is stored on the file system of the z-leaf server as data files, where the experiment is controlled by the experimenter (bottom of diagram). Files are saved in both a proprietary format and excel files for easy import into statistical analysis packages such as SAS, R, STATA, SPSS, etc. A special module of R is available (at http://www.kirchkamp.de) to easily import data from these formats maintaining the structure of the data objects and is available.

Each z-leaf client runs independently (subjects on the right of the diagram) but connects to the server via the network to display market conditions or values. Response times within the application are excellent and transactions occur sub-second between the server and each Z-Leaf client. Once the experiment has concluded the z-leaf client shows a blank screen and awaits for the next experimental session to begin again, while the Z-leaf server saves the results in a separate file and resets the values from the previous session, which begins when the experimenter runs the next session with new participants. Researchers in economics have used z-tree to run experiments on many different topics as summarized in the table below. Some specific example studies include Anderhub et al. (2002a, b) and Hey and Morone (2004).

Economic models and treatments supported by z-tree

Public goods game (Falkinger mechanism) (punishment mechanism) | Conditional cooperation | Oligopoly experiments |

|---|---|---|

Ultimatum game | Comparative advantage | Money illusion |

Prisoner’s dilemma game | Principal agent | Absolute stranger |

Battle of the sexes | Posted offer | Bargaining |

Double auction (in an asset market) (with effort choice) | Two person two strategy (simultaneous) (sequential) | Collective action Collective markets |

1.2 Instructions for buyers

1.2.1 General overview

You will be presented with one item to place a bid. Each product has a specific value to you. A small time cost is assessed to you as the round progresses. During each round you will try to acquire each of the items for the best (lowest) possible price. You must work with other buyers to purchase the product. It requires two buyers to agree on a price before the seller can accept an offer. Your goal is to generate as much cumulative profit as possible, which is equal to the values of the products minus the sum of amounts you pay for them and your time costs. Each round will last two and a half minutes. There will be one practice followed by a number of “real” rounds. The total time for the entire exercise will be approximately one hour.

1.2.2 Bidding rules

Any buyer may submit a bid. You may join a bid that is no greater than the value of the item. You may submit a new bid as long as it is greater than the highest bid. Start your bidding low to maximize potential profit. New bids can only be done in increments of 1; therefore they can be 1 dollar higher than the maximum bid or 1 dollar lower than the minimum bid. Once you join a bid you will not be able to remove yourself from that offer. Once two bidders join an offer, the bid is automatically submitted to the seller. If the value of the item drops below the current bid price, the offer will be removed. The value of an item may be different for each buyer.

1.2.3 Making money

The profit you earn is equal to the value of the item bought, the bid you submit for the item, minus the time cost you spend for it. For example, if “item A” is worth $90 to you and you won the item at the end of the auction with a joint bid of $65, and your time cost spent is $5, you will earn a profit of ($90 − $65) − $5 = $20.

Your total game profit will be equal to the total of all your ten individual round profits.

1.2.4 Key summary points

-

Your goal is to make money.

-

You have a cost associated with the time you spend in the auction.

-

Keep a close watch on the clock especially as it counts down to the end.

-

Make sure you work with other buyers to get the best possible price.

-

Remember you need at least two buyers to make an offer.

-

Start your bidding low to give yourself the best possible profit.

1.3 Instructions for sellers (small groups)

1.3.1 General overview

You will be presented with two units of one item that you want to sell in an auction. You have a small cost associated with the time you spend in the auction. During each round you will try to sell your item for the highest possible price. Your goal is to generate as much profit as possible, which is equal to the price at which you sell the item minus the time cost you spend for it. Each round will last two and a half minutes. There will be one practice round and a number of “real” rounds. The total time for the entire exercise will be approximately one hour. Instructions for the big group treatment are similar and not included.

1.3.2 Bidding rules

Your product is automatically entered into the auction allowing bidders to submit bids, which you may accept. A bid will only be submitted to you when 2 buyers join the offer. You may choose to accept the bid at anytime or allow the bid to expire. The auction will end once you accept an offer or at the end of, 150 s (two and a half minutes).

1.3.3 Making money

The round profit you earn is equal to the highest offer you accept for the item minus the time cost for the item. For example, if the offer you accept is $90 at the end of the auction, and your time cost is $10, you will earn a profit of $90 − $10 = $80. Your total game profit will be equal to the total of all your round profits.

1.3.4 Key summary points

-

Your goal is to make money.

-

Try and get the largest profit possible.

-

You have a cost associated with the time you spend in the auction.

-

Keep a close watch on the clock especially as it counts down to the end.

1.4 Example buyer screens

1.5 Example seller screen

1.6 Example chatbox messages

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, Y., Pelaez, A. & Lang, K.R. Designing and evaluating business process models: an experimental approach. Inf Syst E-Bus Manage 14, 767–789 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10257-014-0257-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10257-014-0257-0