Abstract

Applying segment-wise altimetry-based gravest empirical mode method to expendable bathythermograph temperature, Argo salinity, and altimetric sea surface height data in March, June, and November from San Francisco to near Japan (30∘ N, 145∘ E) via Honolulu, we estimated the component of the heat transport variation caused by change in the southward interior geostrophic flow of the North Pacific subtropical gyre in the top 700 m layer during 1993–2012. The volume transport-weighted temperature (T I) is strongly dependent on the season. The anomaly of T I from the mean seasonal variation, whose standard deviation is 0.14∘C, was revealed to be caused mainly by change in the volume transport in a potential density layer of 25.0−25.5σ 𝜃 . The anomaly of T I was observed to vary on a decadal or shorter, i.e., quasi-decadal (QD), timescale. The QD-scale variation of T I had peaks in 1998 and 2007, equivalent to the reduction in the net heat transport by 6 and 10 TW, respectively, approximately 1 year before those of sea surface temperature (SST) in the warm pool region, east of the Philippines. This suggests that variation in T I affects the warm pool SST through modification of the heat balance owing to the entrainment of southward transported water into the mixed layer.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The North Pacific subtropical gyre consists of the poleward western boundary current (i.e., the Kuroshio) and the equatorward return flow in the interior region; on the whole, it transports a huge amount of heat poleward (e.g., Bryden et al.1991; Bryden and Imawaki2001). In addition to the change in the gyre volume transport (Sugimoto et al. 2010; Nagano et al. 2013), variation in the net heat transport of the subtropical gyre results from changes in the volume transport distribution with respect to temperature in the Kuroshio or equatorward interior return flow. Changes in the volume transport distributions of these currents with respect to temperature are accounted for by their volume transport-weighted temperatures (Bryden et al. 1991).

Of these components, we focus here on variation in the heat transport generated by basin-scale change in the gyre interior flow. White (1975) estimated long-term change in the volume transport of the gyre interior flow across the 30∘ N latitude by the sea surface dynamic height (SSDH) difference between two very distant points off the coasts of Asia and Baja California. To calculate the volume transport-weighted temperature of the gyre interior flow (T I), trans-Pacific hydrographic sections resolving the spatial variations of the interior flow and temperature are required.

Estimates of T I are limited to the World Ocean Circulation Experiment (WOCE) P02 line at 30∘ N latitude (Bryden and Imawaki 2001; Nagano et al. 2009) and the PX37 (from San Francisco to Honolulu) and PX40 (from Honolulu to Japan) lines (Uehara et al. 2008; Nagano et al. 2012). Bryden and Imawaki (2001) and Nagano et al. (2009) calculated T I to be 15.8 and 15.4∘C based on the WOCE P02 observations in October 1993–January 1994 and June–August 2004, respectively. Because T I is an essential factor in the gyre net heat transport, it is potentially related to climate variations such as the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) (e.g., Mantua et al.1997). T I can also be considered as the temperature of water transported by the gyre interior flow, and it is expected to be related to subduction in the North Pacific central region. Recently, Toyama et al. (2015) suggested that the subduction rate is related to the positive PDO phase with a lag of a few years. However, it is uncertain whether or not the difference between the two estimated T I values (0.4∘C) is attributable to climate variations.

On the basis of five expendable bathythermograph (XBT) sections collected by voluntary ships at the PX37 and PX40 lines, Nagano et al. (2012) revealed a greater variability in T I, with a maximal difference of 0.8∘C. This was probably associated with seasonal change in the volume transport distribution with respect to potential density. The PX37 and PX40 observations were conducted at irregular intervals in space and time; therefore, the almost simultaneously obtained trans-Pacific sections from San Francisco to near Japan are scarce. Thus, the variation in T I on interannual and longer timescales is not distinguishable from the seasonal variation when using in situ XBT sections.

To distinguish the interannual and longer timescale variations from the seasonal variation, a dataset with extensive coverage and high resolution in both space and time across the North Pacific for a sufficiently long duration is required. However, this is almost impossible to achieve using shipboard hydrographic surveys alone. For more than two decades, satellite altimeters have measured global sea surface height (SSH) at a spatiotemporal resolution that is high enough to resolve spatial variation in the subtropical gyre (e.g., Ducet et al.2000). The SSH data are useful for investigating interannual and longer timescale variations in the gyre interior flow. In the subtropical region, year-to-year variation in SSH is principally attributed to the baroclinic variation associated with the variation of the main thermocline (e.g., Kakinoki et al.2008; Nagano et al.2013). Baroclinic changes in the gyre interior flow are expected to be observed at the PX37 and PX40 lines by many voluntary ship XBT casts performed during the altimetric SSH observations.

By taking a sufficiently deep reference level, we can obtain SSDH based on hydrographic data; this is linearly related to altimetric SSH. The vertical distributions of temperature and salinity are represented as functions of SSDH, as performed in the Antarctic Circumpolar Current region by Sun and Watts (2001) and Swart et al. (2010), in the North Pacific western subarctic gyre region by Nagano et al. (2016), and in other regions. Through the linear relationship between SSDH and SSH, the vertical hydrographic distributions can be inferred by altimetric SSH. This method, which converts SSH data to hydrographic distributions, is termed the altimetry-based gravest empirical mode (AGEM) method. If the relationship between SSDH, SSH, and hydrographic profiles is determined from the altimetric and hydrographic data at the PX37 and PX40 lines, the AGEM method provides a sufficiently long time series of the hydrographic section of the North Pacific subtropical gyre interior flow.

In this study, we calculate the AGEM-based temperature, salinity, and geostrophic velocity for the PX37 and PX40 lines in order to complement the hydrographic data along these lines with the SSH data and to examine the variation in T I. We describe the data and the AGEM method in Section 2. In Section 3, we illustrate the seasonal and year-to-year variations in T I, the associated changes in the vertical structure of flow, and the quasi-decadal (QD) timescale variation of T I and its related variation in the gyre net heat transport (\(Q^{\prime }_{\mathrm {I}}\)). In Section 4, we summarize our results, discuss the relationship between T I and the PDO, and comment on the variation in the volume transport-weighted salinity in the subtropical gyre interior flow (S I).

2 Data and methods

2.1 Hydrographic and SSH data processing

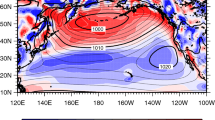

Temperature data down to a depth of approximately 760 m at the PX37 line (Fig. 1) have been obtained at horizontal intervals of approximately 60 km typically four or five times per year in various months since 1991 by Sippican Deep Blue XBT (Lockheed Martin Sippican, Inc.) as part of the Scripps High Resolution XBT Program (http://www-hrx.ucsd.edu). At the PX40 line, temperature data down to a 760 m depth have been collected at longitudinal intervals of 0.5∘ since 1998 approximately three times per year typically in March, June, and November by TSK T-7 XBT (Tsurumi-Seiki Co. Ltd.) as part of the Japan-Hawaii Monitoring Program (http://www.pol.gp.tohoku.ac.jp/kizu/jahmp/jahmp-e.htm).

Because salinity data were not collected for either line, we obtained them from 1∘×1∘ gridded hydrographic dataset, which was compiled using Argo data from 2001 by Hosoda et al. (2008) and are available as Grid Point Value of the Monthly Objective Analysis using the Argo data (MOAA GPV) in the Japan Argo database (http://www.jamstec.go.jp/ARGO/argoweb/argo). In this study, we used the XBT temperature data and Argo-based salinity data during 2001–2012 for the PX37 and PX40 lines.

Temperature profiles were vertically averaged over 10 m to eliminate small-scale noise features and then gridded from 10 to 700 m at vertical intervals of 10 m. The salinity data were averaged at the grid points of MOAA GPV within a horizontal distance of 150 km from individual XBT sites. They were further vertically interpolated down to 700 m at intervals of 10 m. Based on the temperature and salinity data, we calculated SSDH (H XBT, in meters), integrating from 10 to 700 m depth, using

where g is the gravitational acceleration and δ is the specific volume anomaly derived from the XBT temperature and Argo salinity data. From 10 to 700 m, the vertical integration along the z axis was discretized into the summation of the 10-m averaged δ value multiplied by the vertical interval of 10 m.

The depth of the XBT measurements was determined using the fall-rate equation proposed by Hanawa et al. (1995). Kizu et al. (2011) reported that Hanawa et al.’s correction method yields positive and negative fall rates for TSK T-7 and Sippican Deep Blue probes; in the present case, these depth biases result in temperature biases of up to 0.07 and −0.03∘C, respectively. Furthermore, data collected by Sippican Deep Blue XBT are known to be subject to time-varying biases in both depth and temperature (e.g., Cowley et al.2013), which are reported to cause positive temperature biases of up to 0.1∘C for the study period. Therefore, by integrating the vertically uniform error added to the observed temperature profiles, we estimated the error in H XBT to be approximately 2 cm. This is smaller than the error of the altimetric SSH anomalies (∼3 cm) (Le Provost 2001). The H XBT error due to the error in the Argo salinity (∼0.01, Hosoda et al.2008) is approximately 0.5 cm, which is even smaller than the error originated from the XBT temperature bias.

Weekly SSH anomalies during 1993–2012 were obtained from the Archiving, Validation and Interpretation of Satellite Oceanographic (AVISO) delayed-time updated mapped data (http://www.aviso.altimetry.fr/duacs/) (AVISO 2008). Because SSH anomalies are generally less reliable near the coast, data from regions shallower than 1000 m were excluded from the analysis. We added the SSH anomalies to the climatological SSDH values relative to 1000 dbar based on the World Ocean Atlas 2005 (Fig. 1) (Locarnini et al. 2006; Antonov et al. 2006) to obtain absolute SSH (H ALT) in meters.

2.2 Segment-wise AGEM method

As outlined in Section 1, we estimated temperature and salinity sections of the PX37 and PX40 lines using the AGEM method. However, it should be noted that vertical structures of temperature and salinity greatly vary along the lines (Uehara et al. 2008; Nagano et al. 2012). In this paper, to account for these spatial variations, we separated the PX37 and PX40 lines into three and five overlapping segments, respectively: 120–140∘W (PX37-1), 135–150∘W (PX37-2), 145–157∘W (PX37-3), 157–175∘W (PX40-1), 170∘W–175∘E (PX40-2), 165–180∘E (PX40-3), 155–170∘E (PX40-4), and 145–160∘E (PX40-5). Also, to account for the seasonal variation, we performed AGEM estimation for March, June, and November individually. With this separation, a sufficiently large number of XBT temperature and Argo salinity profiles (exceeding 270 profiles for each segment) could be used to construct AGEM fields for each segment and each month.

We constructed the segment-wise AGEM fields of potential temperature and salinity, i.e., the relationship between hydrographic profiles and H XBT, interpolating the data by a Gaussian weight function with an e-folding scale of 2.5 cm to remove the mismatch between the XBT temperature and the gridded Argo salinity. The AGEM fields of potential temperature down to a depth of 700 m for the eight segments in March, June, and November are shown in Fig. 2. The main thermocline, represented by a sharp vertical temperature gradient approximately between 8 and 18∘C, commonly deepens in all segments as SSDH, i.e., H XBT, increases. Furthermore, seasonal variation in stratification in the near-surface layer and spatial change in the main thermocline thickness along the lines are identified. In other words, even for a single value of H XBT, potential temperature profiles are substantially different in terms of months and locations (segments).

In Fig. 3, we show the potential temperature AGEM fields for the eight segments in the individual months with respect to H XBT at a depth of 400 m, around which the main thermocline exists in the segments east of PX40-2. Potential temperature values deduced from XBT measurements (dots) largely distribute around AGEM-based values (curves) for each segment. Because of strong smoothing with respect to H XBT, AGEM-based potential temperatures deviate from XBT values toward the ends of the AGEM curves, particularly at segments PX40-4 and PX40-5. Accordingly, high-frequency, large-amplitude variations in H XBT near the ends of the AGEM curves are filtered out by the AGEM method. Potential temperatures observed by XBT at the PX37 and PX40 lines are distributed over a wide range (exceeding 6∘C) for a range of H XBT values between approximately 1.4 and 1.8 m. By constructing segment-wise AGEM fields, regional characteristics of the potential temperature (e.g., thermostads corresponding to the mode waters) are reasonably represented. The potential temperature root-mean-square (RMS) errors for the segments are between 0.45 and 0.98∘C (Table 1). The salinity AGEM fields (not shown) are largely consistent with typical temperature-salinity relationships in each region.

Plots of H XBT versus potential temperature at 400 m depth in a March, b June, and c November at eight segments: PX37-1 (red), PX37-2 (blue), PX37-3 (orange), PX40-1 (green), PX40-2 (purple), PX40-3 (cyan), PX40-4 (magenta), and PX40-5 (black). Values based on XBT measurements and AGEM method are shown by dots and curves, respectively

H ALT is linearly related to H XBT, with correlation coefficients of 0.72–0.95 (Table 2), which are substantially higher than the 1 % significance level (i.e., within the 99 % confidence limit) based on the Student’s t test. Linear regressions between H XBT and H ALT were performed for each segment and month as

where a and b were obtained by the least square method (Table 2). The obtained values of the regression slope, i.e., a, are slightly larger than, or close to, unity. With the exception of the westernmost segment (i.e., PX40-5), the RMS differences are smaller than 6 cm, which is of the same order of magnitude as errors in the H ALT data. At PX40-5, where mesoscale eddies prevail, the RMS difference is approximately 11 cm. This large RMS difference is mainly due to the deeper mesoscale eddy contributions, which are not included in H XBT. Mesoscale eddies have time scales shorter than approximately five months. Therefore, to eliminate the effect of mesoscale eddies from H ALT, we smoothed H ALT using a fifth-order Butterworth filter with a half-power period of five months.

The elimination of the mesoscale fluctuations by the low-pass filter reduces the sensitivity of the results to the location of the western end point. As a test, we computed T I with the western end point fixed at 29∘9′ N, 150∘ E. The results were quite similar to those with the end point fixed at 30∘ N, 145∘ E. Therefore, we concluded that the results described below are independent of the location of the western end point. Hereafter, we present the results on the interior flow of the subtropical gyre with the western end point set at 30∘ N, 145∘ E. This location corresponds to the southern edge of the recirculation gyre south of the Kuroshio Extension (Inoue and Kouketsu 2016).

By converting the smoothed H ALT to H XBT (Eq. 1 and Table 2) and referring to the AGEM fields by H XBT for each month (Fig. 2), we estimated the potential temperature (𝜃), salinity (S), and potential density (σ 𝜃 ) profiles in the individual months during 1993–2012 at longitudinal intervals of approximately 0.5∘ from the smoothed H ALT. Furthermore, each AGEM-derived hydrographic section was spatially smoothed using a five-degree longitude running mean along the lines to remove the jumps across the segments.

In Fig. 4a, b, we show AGEM-derived potential temperature/density sections for states of relatively low and high T I anomalies in June 1993 and June 2007, respectively (year-to-year T I change will be described in Section 3). The AGEM method reproduces the seasonal thermocline in the near-surface layer and a vertically uniform potential density layer between 25.0 and 25.5 kg m−3 (expressed as 25.5σ 𝜃 hereafter) west of around 170∘ E. An eastward ascension of the potential density surfaces lower than 25.5σ 𝜃 suggests southward baroclinic volume transport. These characteristics coincide with those in Fig. 2 of Nagano et al. (2012), although mesoscale eddy structures shown in that study were filtered out in the present study by the spatial and temporal smoothing. By separating the PX37 and PX40 lines into the eight segments and constructing the AGEM fields for each month, the AGEM method provided plausible hydrographic sections.

In addition, we used the monthly 1∘×1∘ gridded hydrographic data collected by Argo floats, Roemmich-Gilson Argo Climatology (http://sio-argo.ucsd.edu/RG_Climatology.html), which was compiled by Roemmich and Gilson (2009). In order to investigate the dependency of the estimated T I on reference depth, the calculation was performed with reference depths of 700 and 1500 dbar for the period 2004–2012. They are quite similar to each other, with a correlation coefficient of 0.93. The mean value with a reference depth of 700 dbar is 1.3∘C higher than that with a 1500 dbar reference depth. Despite the significant bias in T I, its variation is almost independent of reference depth. It should be noted that in addition to the bias caused by the choice of reference depth, there would exist T I bias derived from that of XBT temperature. Therefore, in this paper, we mainly focus on the anomaly of T I from the mean seasonal variation.

3 Results

3.1 AGEM-based volume transport-weighted temperature

We calculated T I of the interior flow across the section along the PX37/40 line above a depth of 700 m (Fig. 5a), as

where the x coordinate is set along the line from the western end point (30∘ N, 145∘ E) to the point off San Francisco (38∘ N, 124∘ W), v is geostrophic velocity calculated with a reference depth of 700 m, and V I is volume transport across the section. It is obvious that T I is seasonally dependent, as was suggested by Nagano et al. (2012) based on five in situ hydrographic sections. The mean values in March, June, and November are 15.32, 15.48, and 15.87∘C, respectively. For comparison, T I values based on the WOCE P02 data by Bryden and Imawaki (2001) and Nagano et al. (2009) are shown using stars in Fig. 5a. Because the difference between the two estimated values (0.4∘C) is close to that between the November and June mean values (0.39∘C), it is likely attributable to the mean seasonal variation.

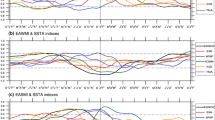

a Volume transport-weighted temperature of the subtropcial gyre interior flow T I in the top 700 m layer at PX37/40 line in March (asterisks), June (circles), and November (dots), and those at P02 line (stars) in November 1993 (Bryden and Imawaki 2001) and June 2004 (Nagano et al. 2009). Horizontal solid, dashed, and dashed-dotted lines show mean values in March, June, and November, respectively. b T I after removing the mean seasonal variation and the yearly time series interpolated using values within two standard deviations (thick solid line). T I based on Argo data during 2004–2012 is shown by thin solid line

Figure 6a, b show all distributions of volume transport with respect to potential density and the mean distributions in individual months from 1992 to 2012, respectively. The distributions above the isopycnal of approximately 25.1σ 𝜃 are clearly distinguishable among these months. The primary peak in volume transport exceeding 3 Sv (1 Sv=106 m3 s−1) in March (green lines) remains stable in a layer around the isopycnal of 24.9σ 𝜃 . In June (magenta lines), the primary peak frequently descends to a deeper layer below the depth of the isopycnal of 25.0σ 𝜃 (Fig. 6a), where the standard deviation of the volume transport is larger than that in the overlying layer (Fig. 6b). In November (blue lines), the volume transport distributes widely in deep layers below the isopycnal of 24.5σ 𝜃 and has an additional significant peak in a layer around 24.1σ 𝜃 . The existence of the shallow peak in volume transport causes very high T I in November (dots in Fig. 5a). Therefore, the seasonal variation in T I is associated with the distinct seasonal change in volume transport distribution with potential density.

a Distributions of volume transport at PX37/40 line with respect to potential density σ 𝜃 in March (green), June (magenta), and November (blue). b Mean distribution for the individual months (thick lines) together with the range of one standard deviation (shades) above and below the mean value. Vertical thin black line indicates zero volume transport. Volume transport was calculated at the potential density intervals of 0.25 kg m−3. Positive value indicates southward transport

3.2 Anomaly of T I from mean seasonal variation

Year-to-year change in the volume transport distribution yields interannual variation in T I, as shown in Fig. 5b. The standard deviation of the T I anomaly is 0.14∘C. In November 2003 and November 2008, the values of T I are lower than the November mean value minus twice the standard deviation. These extremely low T I values are attributed to the abrupt reduction in volume transport in a layer around the isopycnal of 25.4σ 𝜃 . The depths of the main pycnocline indicated by the isopycnal of 25.5σ 𝜃 in November 2003 (dashed line in Fig. 7) and November 2008 (thick solid line) are substantially shallower than the mean depth of the isopycnal (thin solid line) to the west of approximately 160 and 155∘ E, respectively. Particularly in November 2008, the upward isopycnal displacement from the mean depth reaches approximately 50 m at the western end point of the PX40 line. The fluctuations appear to have horizontal scales larger than 1000 km and are attributable to variation in the subtropical and/or recirculation gyres.

With the exception of the above extreme cases, we could not identify a significant year-to-year difference between potential temperature/density sections in relatively low- T I and high- T I states (as exemplified in Fig. 4a, b, respectively); however, the difference resulting in the year-to-year variation of T I might be revealed by integrating temperature and geostrophic current velocity along the entire line.

In principle, the variation in T I can be affected by both changes in temperature and geostrophic current velocity in the interior region. To reveal the factors contributing to the year-to-year variation in T I, referred to as \(T_{\mathrm {I}}^{\prime }\) hereafter, we separate 𝜃 and v into their seasonal mean variations and the anomalies as \({\theta }=\overline {\theta }+{\theta }^{\prime }\) and \(v=\overline {v}+v^{\prime }\), where 𝜃 ′ and v ′ are the anomalies from the long-term mean values in each month, \(\overline {\theta }\) and \(\overline {v}\), respectively. Here, a positive v indicates southward velocity. We partitioned the vertical integration range of Eq. 3 into layers between the depths (D) of the isopycnals of σ 𝜃 ±Δσ 𝜃 /2. As a result, \(T_{\mathrm {I}}^{\prime }\) is decomposed into three components with respect to potential density as

where

We set Δσ 𝜃 =0.25 kg m−3, which is sufficient for the expected temperature variation of the mode waters, and we calculated \(T^{\prime }_{1}\), \(T^{\prime }_{2}\), and \(T^{\prime }_{3}\) in isopycnal layers from 22.5 to 27.5σ 𝜃 .

The standard deviations of these components are shown in terms of potential density σ 𝜃 in Fig. 8a. Obviously, the dominant component of the T I anomaly originates from the anomaly of geostrophic current velocity, i.e., \(T^{\prime }_{2}\), (solid line) in all isopycnal layers. The variation is particularly large in layers above the isopycnal of 25.5σ 𝜃 and reaches its maximum in a layer between the isopycnals of 25.0 and 25.5σ 𝜃 . The maximum value exceeds 0.2∘C. The contribution from the variation in potential temperature, i.e., \(T^{\prime }_{1}\), (dashed line) is one or two orders of magnitude smaller than that from \(T^{\prime }_{2}\). The variation in \(T^{\prime }_{3}\) (dotted line) is practically negligible.

a Standard deviations of \(T_{1}^{\prime }\) (dashed line), \(T_{2}^{\prime }\) (solid line), and \(T_{3}^{\prime }\) (dotted line) in Eqs. 4–6 with respect to potential density σ 𝜃 . b Correlation coefficient (dashed line) and covariance (solid line) between \(T_{2}^{\prime }\) and \(T_{\mathrm {I}}^{\prime }\). Vertical solid and dotted lines indicate correlation coefficients of zero and ±0.33, the 1 % significance level (the confidence limit of 99 %). Values in a and b were calculated at potential density intervals of Δσ 𝜃 =0.25 kg m−3

To examine the relationship between \(T^{\prime }_{\mathrm {I}}\) and \(T^{\prime }_{2}({\sigma }_{\theta })\), we computed their covariance (solid line in Fig. 8a), which is defined as

where t n (n=1,2,⋯ ,N) is time. This shows the maximum value in a layer between the isopycnals of 25.0 and 25.5σ 𝜃 , where the standard deviation of \(T^{\prime }_{2}\) (solid line in Fig. 8a) is also maximal. In addition, the correlation coefficient, i.e., the covariance normalized by the standard deviations of \(T^{\prime }_{\mathrm {I}}\) and \(T^{\prime }_{2}({\sigma }_{\theta })\), (dashed line in Fig. 8b) is greater than 0.33 (the 99 % confidence limit based on the Student’s t test) in the layers above an isopycnal of 26.5σ 𝜃 . Thus, the year-to-year variation in \(T^{\prime }_{2}({\sigma }_{\theta })\) in a layer between the 25.0 and 25.5σ 𝜃 isopycnal surfaces contributes to that of \(T^{\prime }_{\mathrm {I}}\). The anomaly of the volume transport in the potential density layer (Fig. 9) is largely similar to that of T I (Fig. 5b). The anomaly of T I is principally attributable to the volume transport anomaly from the mean seasonal variation in a layer between the isopycnals of 25.0 and 25.5σ 𝜃 .

Same as Fig. 5b, but for AGEM-based volume transport in the layer between isopycnals of 25.0 and 25.5σ 𝜃 . Positive value indicates southward transport

Yearly time series of the T I anomaly obtained by a Gaussian smoothing with an e-folding time of 6 months is shown by the thick solid lines in Figs. 5b and 10a. During the study period, T I varies on a decadal or shorter, i.e., QD, timescale with marked peaks in 1998 and 2007. To examine the reliability of the yearly T I estimated by the AGEM method and the Gaussian smoothing for the data sampled in uneven time intervals, we illustrate yearly time series of the T I anomaly based on Roemmich-Gilson Argo Climatology (thin solid line in Fig. 5b). Although the values based on the Argo data from 2004 to 2005 are less accurate than those in the remaining period due to the sparse Argo float coverage, the peaks in 2007 and 2010 (thin solid line) correspond well with those of the AGEM-based T I (thick solid line). The correlation coefficient between them is 0.74, which is statistically significant within the 95 % confidence limit. Thus, the QD-scale variation of the AGEM-based T I is verified by the Argo data.

a Yearly anomaly of T I normalized by its standard deviation and b its related variation of the net heat transport of the subtropical gyre, i.e., \(Q^{\prime }_{\mathrm {I}}\) in Eq. 8 (solid lines). For comparison, monthly SST anomaly averaged in the North Pacific warm pool region (10–20∘ N, 125–160∘ E) and NPI, which are normalized by the standard deviations, are shown by dashed and dotted lines, respectively. Average SST anomaly in the warm pool region and NPI were smoothed by a fifth-order Butterworth filter with half-power period of 3 years

3.3 Impact of year-to-year T I variation on the net heat transport

The component of the net poleward heat transport variation of the subtropical gyre, which is related to T I variation due to basin-scale interior flow change, can be estimated as

where ρ is seawater density, C p is the specific heat capacity of seawater at constant pressure, and \(\overline {V}_{\text {STG}}\) is the average subtropical gyre volume transport. We set ρ C p and \(\overline {V}_{\text {STG}}\) to 3.99×106 J K−1 m−3 and 26.2 Sv, respectively (following the estimations by Nagano et al.2010). As in Fig. 10b, \(Q^{\prime }_{\mathrm {I}}\) reaches minima of -6 and -10TW (TW = 1012 W) in 1998 and 2007, respectively, when T I has significant maxima. The reductions in heat transport due to the enhancements of T I are equivalent to up to approximately 5 % of the absolute values of the gyre net heat transport (0.19–0.22 PW, where PW =1015 W), as estimated by Nagano et al. (2010).

The water transported by the interior southward subsurface flow through the PX37/40 line concentrates on the North Pacific warm pool region (east of the Philippines), ascending along the shoaling main pycnocline and subsequently being entrained into the mixed layer. In the annual mean state, the sea surface thermal forcing and heat advection by the Ekman and geostrophic currents are principally balanced by the entrainment of deep cold water through the mixed layer bottom (Niiler and Stevenson 1982; Qu 2003). The enhancement of T I, or the reduction of \(Q^{\prime }_{\mathrm {I}}\), in 1998 and 2007 might be related to the attenuation of cooling by the entrainment into the mixed layer east of the Philippines. Sea surface temperature (SST) averaged in the area of 10–20∘ N, 125–160∘ E (dashed line in Fig. 10) shows peaks in 1999 and 2008, which occur one year after the T I peaks (\(Q^{\prime }_{\mathrm {I}}\) troughs).

Assuming the thermal forcing at the sea surface and the horizontal advections to be invariant, the increasing rate of the temperature in the warm pool region is equivalent to the decreasing rate of cooling due to the entrainment from the mixed layer bottom. Under this assumption, the warm pool SST would increase by an amount of heat that is equivalent to the reduction of \(Q^{\prime }_{\mathrm {I}}\). The increasing rate of SST that is due to a \(Q^{\prime }_{\mathrm {I}}\) reduction of 10 TW is evaluated to be approximately 0.2∘C year−1 in a winter mixed layer of ∼100 m thickness (for example, see Fig. 5 in de Boyer Montégut et al.2004) in the specified area. This value is sufficiently large to contribute to the SST anomaly of 0.25∘C in 2008, and it is equivalent to 13 % of the annual mean cooling rate due to vertical entrainment (approximately −1.6∘C year−1) estimated by Qu (2003).

4 Summary and discussion

Applying the segment-wise AGEM method to XBT temperature, Argo salinity, and altimetric SSH data at the PX37 (San Francisco to Honolulu) and PX40 (Honolulu to near Japan, 30∘ N, 145∘ E) lines, we estimated the AGEM-based temperature, salinity, and geostrophic velocity sections down to 700 m depth from 1993 to 2012. We examined the volume transport-weighted temperature of the southward interior flow of the North Pacific subtropical gyre (T I). T I is substantially dependent on the seasonal change in volume transport distribution with potential density (as Nagano et al.2012 suggested based on in situ hydrographic data alone). The anomaly of T I from the mean seasonal variation, whose standard deviation is 0.14∘C, is found to originate from the change in the volume transport distribution in a layer between the isopycnals of 25.0 and 25.5σ 𝜃 .

We found that T I varies on the QD timescale, and the QD-scale variation is confirmed by the analysis of the Argo gridded data from 2004 to 2012. Marked peaks of the QD-scale T I variation are found in 1998 and 2007, approximately 1 year before the peaks of SST averaged in the North Pacific warm pool region, east of the Philippines. This is thought to be the reduction of the net heat transport of the North Pacific subtropical gyre by 6 and 10 TW, respectively. The reduction of the heat transport is equivalent to up to approximately 5 % of the absolute values of the net heat transport. It is suggested that the QD-scale increase of T I corresponds to the reduction in the rate of cooling due to the entrainment of water into the warm pool mixed layer by approximately 13 % of the annual mean rate. This result suggests the sizable impact of the QD-scale variation in T I on the SST change in the warm pool region.

To examine the relationship between the QD-scale variation of T I and climate variation, we show the North Pacific Index (NPI), which was defined as the area-weighted sea-level atmospheric pressure in the region of 30–65∘ N, 160∘ E–140∘ W by Trenberth and Hurrel (1994) (dotted lines in Fig. 10). The NPI is related to the dominant variation in SST by the PDO and varies on a QD timescale with troughs in 1997 and 2003, representing the intensification of the Aleutian Low. The enhancement of the subduction rate a few years after the positive PDO phase (NPI troughs) suggested by Toyama et al. (2015) are likely discernible by the peaks in T I (solid line) with a lag of up to 4 years. Although the time series of T I is not sufficiently long to make firm conclusions about the relationship between T I and the NPI (the equivalent degree of freedom is 2), the peaks of the T I anomaly, i.e., the troughs of the net poleward heat transport, seem to be caused by the intensification of the Aleutian Low associated with the positive PDO phase. This hypothesis should be tested by AGEM methods that are modified to allow application to areas other than the PX37 and PX40 lines using a more comprehensive dataset.

Finally, we comment on the volume transport-weighted salinity in the subtropical gyre interior flow, i.e., S I. As the QD-scale variation of T I is related to that of the warm pool SST, the variation in S I may affect the sea surface salinity (SSS) in the tropical region. By using the data derived from the AGEM method, we calculated S I and show the anomaly from the mean seasonal variation in Fig. 11. The anomalies of S I (thick line) and T I covary on the QD timescale. Hasegawa et al. (2013) reported the QD-scale variations of upper-ocean temperature and salinity in the warm pool region; their anomalies in the region east of the Philippines were negative during 2002–2005 and positive during 2007–2009. The relationship between warm pool temperature and salinity is similar to that between T I and S I. This supports the idea that SST and SSS in the region are substantially affected by variations in T I and S I, respectively, possibly through the vertical entrainment of water into the mixed layer.

Same as Fig. 5b, but for volume transport-weighted salinity S I

Note that the S I anomaly based on the Argo data (thin line) is depressed in 2009, whereas the AGEM-derived S I anomaly is elevated. This discrepancy may imply that the true variation in S I is attributable to the interannual and/or longer timescale variations of precipitation and evaporation in the extratropical region, in addition to the QD-scale change in the volume transport distribution of the subtropical gyre interior flow. Also, SSS in the central part of the North Pacific subtropical gyre has been reported to have increased during the last several decades due to the intensification of the global hydrological cycle (Hosoda et al. 2009; Durack et al. 2012). The AGEM-based S I has neither a clear increasing nor decreasing tendency. The Argo-based S I appears to have a decreasing trend possibly in response to the global hydrological cycle, although the analysis period is not sufficiently long to elucidate this relationship. In future work, longer time series of S I based on continuing Argo float data will clarify the role of the subtropical gyre in the hydrological cycle.

References

Antonov J I, Locarnini R A, Boyer T P, Mishonov A V, Garcia H E (2006) World ocean atlas 2005, vol 2. U.S. Government Printing Office, Salinity

AVISO (2008) SSALTO/DUACS User Handbook: (M)SLA and (m)ADT Near-Real Time and Delayed Time Products, Tech rep., CLS, Ramonville St Agnes

Bryden H, Imawaki S (2001) Ocean heat transport. In: Siedler H, Church J, Gould J (eds) Ocean Circulation and Climate: observing and modeling the global ocean. Academic, pp 455–474

Bryden H, Roemmich D, Church J (1991) Ocean heat transport across 24∘N in the Pacific. Deep-Sea Res. 38:297–324

Cowley R, Wijffels S, Cheng L, Boyer T, Kizu S (2013) Biases in expendable bathythermograph data: a new view based on historical side-by-side comparisons. J Atmos Oceanic Technol 30:1195–1225. doi:10.1175/JTECH-D-12-00127.1

de Boyer Montégut C, Madec G, Fischer AS, Lazar A, Iudicone D (2004) Mixed layer depth over the global ocean: an examination of profile data and a profile-based climatology. J Geophys Res 109(C12003). doi:10.1029/2004JC002378

Ducet N, Le Traon P Y, Reverdin G (2000) Global high-resolution mapping of ocean circulation from TOPEX/poseidon and ERS-1 and -2. J Geophys Res 105(C8):19,477–19,498

Durack P J, Wijffels S E, Matear R J (2012) Ocean salinities reveal strong global water cycle intensification during 1950 to 2000. Science 336(6080):455–458. doi:10.1126/science.1212222

Hanawa K, Rual P, Bailey R, Sy A, Szabados M (1995) A new depth-time equation for Sippican or TSK T-7, T-6 and T-4 expendable bathythermographs (XBT). Deep-Sea Res 42(8):1423–1451

Hasegawa T, Ando K, Ueki I, Mizuno K, Hosoda S (2013) Upper-ocean salinity variability in the tropical Pacific: case study for quasi-decadal shift during the 2000s using TRITON buoys and Argo floats. J Climate 26:8126–8138. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-12-00187.1

Hosoda S, Ohira T, Nakamura T (2008) A monthly mean dataset of global oceanic temperature and salinity derived from Argo float observations. JAMSTEC Rep Res Dev 8:47–59

Hosoda S, Suga T, Shikama N, Mizuno K (2009) Global surface layer salinity change detected by Argo and its implication for hydrological cycle intensification. J Oceanogr 65:579–586

Inoue R, Kouketsu S (2016) Physical oceanographic conditions around the S1 mooring site. J Oceanogr 72:453–464. doi:10.1007/s10872-015-0342-0

Kakinoki K, Imawaki S, Uchida H, Nakamura H, Ichikawa K, Umatani S, Nishina A, Ichikawa H, Wimbush M (2008) Variations of Kuroshio geostrophic transport south of Japan estimated from long-term IES observations. J Oceanogr 66:373–384

Kizu S, Sukigara C, Hanawa K (2011) Comparison of the fall rate and structure of recent T-7 XBT manufactured by Sippican and TSK. Ocean Sci 7:231–244. doi:10.5194/os-7-231-2011

Le Provost C (2001) Ocean tides. In: Fu L-L, Cazenave A (eds) Satellite altimetry and earth sciences: a handbook for techniques and applications. Academic, pp 267–303

Locarnini R A, Mishonov A V, Antonov J I, Boyer T P, Garcia H E (2006) World ocean atlas 2005, vol 1. U.S. Government Printing Office, Temperature

Mantua N J, Hare S R, Zhang Y, Wallace J M, Francis R C (1997) A Pacific interdecadal climate oscillation with impacts on salmon production. Bull Amer Meteor Soc 78(78):1069– 1079

Nagano A, Ichikawa K, Ichikawa H, Konda M, Murakami K (2009) Synoptic flow structures in the confluence region of the Kuroshio and the Ryukyu Current. J Geophys Res 114(C06007). doi:10.1029/2008JC005213

Nagano A, Ichikawa K, Ichikawa H, Tomita H, Tokinaga H, Konda M (2010) Stable volume and heat transports of the North Pacific subtropical gyre revealed by identifying the Kuroshio in synoptic hydrography south of Japan. J Geophys Res 115(C09002). doi:10.1029/2009JC005747

Nagano A, Ichikawa H, Yoshikawa Y, Kizu S, Hanawa K (2012) Variation of the southward interior flow of the North Pacific subtropical gyre, as revealed by a repeat hydrographic survey. J Oceanogr 68(2):361–368. doi:10.1007/s10872-012-0102-3

Nagano A, Ichikawa K, Ichikawa H, Konda M, Murakami K (2013) Volume transports proceeding to the Kuroshio Extension region and recirculating in the Shikoku Basin. J Oceanogr 3:285–293. doi:10.1007/s10872-013-0173-9

Nagano A, Wakita M, Watanabe S (2016) Dichothermal layer deepening in relation with halocline depth change associated with northward shrinkage of North Pacific western subarctic gyre in early 2000s. Ocean Dynam 66(2):163–172. doi:10.1007/s10236-015-0917-8

Niiler P P, Stevenson J (1982) The heat budget of tropical ocean warm-water pool. J Mar Res 40:465–480

Qu T (2003) Mixed layer heat balance in the western North Pacific. J Geophys Res 108 (C7). doi:10.1029/2002JC001536

Roemmich D, Gilson J (2009) The 2004–2008 Mean and annual cycle of temperature, salinity, and steric height in the global ocean from the Argo Program. Prog Oceanogr 82:81–100. doi:10.1016/j.pocean.2009.03.004

Sugimoto S, Hanawa K, Narikiyo K, Fujimori M, Suga T (2010) Temporal variations of the net Kuroshio transport and its relation to atmospheric variations. J Oceanogr 66(5):611– 619

Sun C, Watts DR (2001) A circumpolar gravest empirical mode for the Southern Ocean hydrography. J Geophys Res 106(C2):2833–2855

Swart S, Speich S, Ansorge IJ, Lutjeharms JRE (2010) An altimetry-based gravest empirical mode south of Africa: 1. Development and validation. J Geophys Res 115(C03002). doi:10.1029/2009JC005299

Toyama K, Iwasaki A, Suga T (2015) Interannual variation of annual subduction rate in the North Pacific estimated from a gridded Argo product. J Phys Oceanogr 45:2276–2293. doi:10.1175/JPO-D-14-0223.1

Trenberth KE, Hurrel JW (1994) Decadal atmosphere-ocean variations in the Pacific. Climate Dynam 9:303–319

Uehara H, Kizu S, Hanawa K, Yoshikawa Y, Roemmich D (2008) Estimation of heat and freshwater transports in the North Pacific using high-resolution expendable bathythermograph data. J Geophys Res 113:C02014. doi:10.1029/2002JC004165

White W B (1975) Secular variability in the large-scale baroclinic transport of the North Pacific from 1950–1970. J Mar Res 33(1):141–155

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the captain and crew of the T/V Miyagi-maru (Miyagi Prefectural Board of Education), Miyagi Prefecture, and members in Scripps High Resolution XBT Program. The MOAA GPV salinity data were provided in the Japan Argo database. The altimeter products were produced by Ssalto/Duacs and distributed by AVISO with support from CNES. Discussion about QD-scale variability with Dr. T. Hasegawa, Dr. I. Ueki, and Dr. M. Nonaka (JAMSTEC) and about AGEM method with Dr. J.-H. Park (KORDI) were insightful. Thanks are also extended to Dr. P. De Mey (Associate Editor of Ocean Dynamics) and anonymous reviewers for their encouraging and helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Pierre De Mey

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Nagano, A., Kizu, S., Hanawa, K. et al. Heat transport variation due to change of North Pacific subtropical gyre interior flow during 1993–2012. Ocean Dynamics 66, 1637–1649 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10236-016-1007-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10236-016-1007-2