Abstract

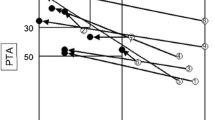

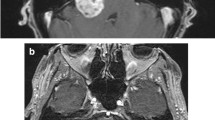

The cochlear nerve is most commonly located on the caudoventral portion of the capsule of vestibular schwannomas and rarely on the dorsal portion. In such a condition, total removal of the tumor without cochlear nerve dysfunction is extremely difficult. The purpose of our study was to identify the frequency of this anatomical condition and the status of postoperative cochlear nerve function; we also discuss the preoperative radiological findings. The study involved 114 patients with unilateral vestibular schwannomas operated on via a retrosigmoid (lateral suboccipital) approach. Locations of the cochlear nerve on the tumor capsule were ventral, dorsal, caudal, and rostral. Ventral and dorsal locations were further subdivided into rostral, middle, and caudal third of the tumor capsule. The postoperative cochlear nerve function and preoperative magnetic resonance (MR) findings were reviewed retrospectively. In 56 patients that had useful preoperative hearing, useful hearing was retained in 50.0 % (28 of 56) of patients after surgery. The cochlear nerve was located on the dorsal portion of the tumor capsule in four patients (3.5 %), and useful hearing was preserved in only one of these patients (25 %) in whom the tumor had been partially resected. This tumor-nerve anatomical relationship was identified in all tumors of <2 cm at preoperative MR cisternography. MR cisternography has the potential to identify the tumor–nerve anatomical relationship, especially in small-sized tumors that usually require therapeutic intervention that ensures hearing preservation. Hence, careful evaluation of the preoperative MR cisternography is important in deciding the therapeutic indications.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Baldwin DL, King TT, Morrison AW (1990) Hearing conservation in acoustic neuroma surgery via the posterior fossa. J Laryngol Otol 104(6):463–467

Ebersold MJ, Harner SG, Beatty CW, Harper CM Jr, Quast LM (1992) Current results of the retrosigmoid approach to acoustic neurinoma. J Neurosurg 76(6):901–909. doi:10.3171/jns.1992.76.6.0901

Fischer G, Fischer C, Remond J (1992) Hearing preservation in acoustic neurinoma surgery. J Neurosurg 76(6):910–917. doi:10.3171/jns.1992.76.6.0910

Gardner G, Robertson JH (1988) Hearing preservation in unilateral acoustic neuroma surgery. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 97(1):55–66

Glasscock ME 3rd, Hays JW, Minor LB, Haynes DS, Carrasco VN (1993) Preservation of hearing in surgery for acoustic neuromas. J Neurosurg 78(6):864–870. doi:10.3171/jns.1993.78.6.0864

Kanzaki J, Ogawa K, O-Uchi T, Shiobara R, Toya S (1991) Hearing preservation in acoustic neuroma surgery by the extended middle cranial fossa method. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 487:22–29

Koos WT, Day JD, Matula C, Levy DI (1998) Neurotopographic considerations in the microsurgical treatment of small acoustic neurinomas. J Neurosurg 88(3):506–512. doi:10.3171/jns.1998.88.3.0506

Nedzelski JM, Tator CH (1984) Hearing preservation: a realistic goal in surgical removal of cerebellopontine angle tumors. J Otolaryngol 13(6):355–360

Post KD, Eisenberg MB, Catalano PJ (1995) Hearing preservation in vestibular schwannoma surgery: what factors influence outcome? J Neurosurg 83(2):191–196. doi:10.3171/jns.1995.83.2.0191

Rhoton AL Jr, Tedeschi H (1992) Microsurgical anatomy of acoustic neuroma. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 25(2):257–294

Samii M, Carvalho GA, Nikkhah G, Penkert G (1997) Surgical reconstruction of the musculocutaneous nerve in traumatic brachial plexus injuries. J Neurosurg 87(6):881–886. doi:10.3171/jns.1997.87.6.0881

Samii M, Gerganov V, Samii A (2006) Improved preservation of hearing and facial nerve function in vestibular schwannoma surgery via the retrosigmoid approach in a series of 200 patients. J Neurosurg 105(4):527–535. doi:10.3171/jns.2006.105.4.527

Samii M, Matthies C (1997) Management of 1000 vestibular schwannomas (acoustic neuromas): hearing function in 1000 tumor resections. Neurosurgery 40(2):248–260

Sampath P, Rini D, Long DM (2000) Microanatomical variations in the cerebellopontine angle associated with vestibular schwannomas (acoustic neuromas): a retrospective study of 1006 consecutive cases. J Neurosurg 92(1):70–78. doi:10.3171/jns.2000.92.1.0070

Sasaki T, Shono T, Hashiguchi K, Yoshida F, Suzuki SO (2009) Histological considerations of the cleavage plane for preservation of facial and cochlear nerve functions in vestibular schwannoma surgery. J Neurosurg 110(4):648–655. doi:10.3171/2008.4.17514

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Comments

Nobutaka Kawahara, Yokohama, Japan

Nakamizo and his colleagues reported the anatomical location of the cochlear nerve in relation to vestibular schwannoma and the results of hearing preservation. According to their data, overall useful hearing preservation rate is 50 %, which varies according to the size of the tumor ranging from 100 % in <1 cm, 56 % in 1–2 cm, to 36–40 % in >2 cm tumors. These are quite excellent to other previous papers. In this manuscript, they further documented anatomical location of the cochlear nerve in relatively small tumors, and described that complete dorsal location of this nerve was observed in 3.5 % and the caudodorsal location in 10.8 %. Since the hearing preservation rate in these cases was worse than in others (25–40 %), they emphasized relatively conservative policy for these patients.

Anatomical location of the cochlear nerve was also reported by Sampath et al. (J Neurosurg 92:70, 2000). According to their data, the percentage of these locations is less 1 %, and they did not mention the rate of hearing according to the location of the nerve. This difference between these manuscripts is unclear but may be due to different subdivision classification or size of tumor included. Nevertheless, Nakamizo et al. reminded us of the importance of the anatomical location of the cochlear nerve on the functional preservation of hearing. In these days, smaller tumors are increasingly found due to wider use of MRI, in which hearing preservation would be the primary goal. In this regards, their data contributed greatly and have taught us an additional factor on hearing preservation, which may also be evaluated preoperatively by MRI.

Lars Poulsgaard, Copenhagen, Denmark

To improve the chance of hearing preservation in vestibular schwannoma surgery, Nakamizo and colleagues have studied the anatomical relationship between the tumor and the cochlear nerves.

This relationship could be established by preoperative MR cisternography in 29 % of all tumors regardless of tumor size. Not surprisingly the identifying rate decreased with increasing tumor size. The location of the cochlear nerves was established during surgery in 65 % of the cases.

The cochlear nerve shows much less anatomical variations than the facial nerve and is most frequently found in the caudoventral portion of the tumor capsule. In the rare case of dorsal locations of the cochlear nerve, hearing preservations was very difficult and often not achieved.

The overall useful hearing preservation was 50 % in the 56 patients that had hearing worth to preserve. Hearing preservation was 100 % in cases with tumor size less than 1 cm.

These excellent results are achieved by using the concept of “subperineurial” or “subcapsular” dissection of the cleavage plane between the tumor capsule and tumor parenchyma.

With the improvement of the MR imaging techniques, Nakamizo and colleagues demonstrate the ability to preoperatively locate the cochlear nerve (especially in small tumors) on the tumor surface. This additional information will undoubtedly contribute to a higher degree of hearing preservation and help us identify the cases where hearing would be less likely.

Madjid Samii, Hannover, Germany

I certainly agree with the authors’ concept that the goal of vestibular schwannoma surgery is maximal tumor removal with preservation of facial and cochlear functions. Precise knowledge of the course of these nerves in regards to the tumor allows including this information in the operative strategy and ultimately should enhance surgical safety.

The authors evaluated intraoperatively the location of the cisternal portion of the cochlear nerve in regards to vestibular schwannoma in 114 patients and attempt to correlate these data with hearing outcome. The nerve was located on the caudoventral portion in 59.5 %, the caudal portion in 18.9 %, the caudodorsal portion in 10.8 %, the ventral portion in 5.4 %, and the dorsal portion in 5.4 %. Based on their analysis, they conclude that total removal of the tumor without cochlear dysfunction is difficult in case the nerve is located on the dorsal tumor capsule.

MR cisternography is a useful method in identifying the cranial nerves in small vestibular schwannoma. The real difficulty, however, is to identify the cochlear nerve in larger tumors that reach the brainstem. In contrast to the facial nerve electrostimulation, there is no positive test to detect the cochlear one. In my experience of approximately 4,000 vestibular schwannoma surgeries, I have never encountered the cochlear nerve dorsal to the tumor. Still, working in the correct dissection plane and gradually stripping off the arachnoidea from the tumor capsule allows preserving the neural structures and to achieve complete tumor removal in most cases.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nakamizo, A., Amano, T., Mizoguchi, M. et al. Dorsal location of the cochlear nerve on vestibular schwannoma: preoperative evaluation, frequency, and functional outcome. Neurosurg Rev 36, 39–44 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-012-0400-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-012-0400-7