Abstract

Background

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is considered to be the most important risk factor for gastric cancer (GC). The International Agency for Research on Cancer reported that H. pylori eradication could reduce the risk of developing GC. Several clinical studies have investigated this relationship as well; however, their results are inconsistent owing to the varied inclusion criteria. To address the effect of H. pylori eradication on GC incidence, we conducted a comprehensive meta-analysis with several subgroup analyses to resolve these inconsistencies.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE and Ichushi-Web to identify randomized control trial and cohort study articles (English or Japanese) through December 2016. Manual searches were also conducted to identify unlisted references in these databases. Eligible studies reported GC incidence as an outcome, with comparisons between H. pylori eradication and control groups. Subgroup analyses were conducted by country, conditions at baseline, and follow-up periods.

Results

We selected 28 studies among 1583 references in the databases and 4 studies by manual searches. The H. pylori eradication group showed significantly lower risk of GC [odds ratio (OR) 0.46; 95% confidence interval 0.39–0.55]. The subgroup analyses indicated that the beneficial effect of eradication was greater in Japan (OR 0.39; 95% CI 0.31–0.49), particularly among those with benign conditions (OR 0.32; 95% CI 0.19–0.54), although none of them was statistically significant. However, reduction of gastric cancer after eradication was significantly greater (p = 0.01) in the groups with long-term (5 years or longer) follow-up (OR 0.32; 95% CI 0.24–0.43) as compared to those with shorter follow-up (less than 5 years) (OR 0.55; 95% CI 0.41–0.72).

Conclusion

Real world data showed that large-scale eradication therapy has been performed mostly for benign conditions in Japan. Since eradication effects in preventing gastric cancer are conceivably greater there, GC incidence may decline faster in Japan than expected from the previous meta-analyses data which were based on multi-national, mixed populations with differing screening quality and disease progression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) is one of the major cancers worldwide, with 952,000 new patients diagnosed in 2012 [1]. The incidence of GC in Korea, Japan, and China ranked first, third, and fifth in the world, respectively [2]. In Japan, GC was the third highest cause of mortality in 2016 and its incidence ranked first in 2013 among all cancers [3].

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is considered to be the most important risk factor for GC. In 1994, the International Agency for Research on Cancer classified H. pylori as a group 1 carcinogenic factor [4]. In 1998, a meta-analysis reported that H. pylori infection increases the risk of GC by approximately twofold [5]. In the past 2 decades, a number of clinical studies have been conducted to further prove whether H. pylori eradication therapy reduces the risk of GC. Several meta-analyses have been completed based on these studies, but the conclusions were inconsistent, because the inclusion criteria were variable [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15].

For instance, Chen et al. [11] reported the pooled relative risk of GC in each study comparing eradication and control groups among individuals with intestinal metaplasia (IM) or dysplasia (designated as IM or beyond) to those without them (designated as before IM). The relative risk of GC was higher in those with IM or beyond, compared to those before IM, leading to the conclusion that patients with IM have passed a “point of no return”. Hence, the benefit of risk reduction of GC through eradication therapy was lost. Lee et al. [12] demonstrated the association between the baseline GC incidence rate and the benefit of eradication therapy. The effect of eradication therapy was greater in populations with a higher baseline GC risk, particularly in those with an incidence rate higher than 150/100,000 person-years. They also mentioned that mass screening and eradication should be carried out in high-risk populations/areas. However, in their meta-analysis, they grouped the studies into low, intermediate, and high baseline incidence by tertiles of incidence rate in the groups not receiving eradication in each study. Therefore, the incidence rate reported in each study might not reflect the actual rates in the general populations/areas, as many studies included in the analysis evaluated patients treated for early neoplastic lesions. Some studies included patients in high-risk populations and others included those in low-risk populations, even though they were conducted in the same country. Moreover, the reason for the greater eradication effects in high-risk populations was not clearly explained. In contrast, exclusion of neoplastic lesions in studies conducted outside of Japan or Korea may not have been rigorous enough, since patients with more dysplastic lesions who would have been excluded in Japan might still have been enrolled in countries other than Japan or Korea. This could have resulted in an underestimation of the preventive effect of eradication on GC.

Therefore, I aimed to carry out a systematic review and meta-analysis to confirm the effect of H. pylori eradication therapy on the incidence of GC, particularly whether the effect is higher in geographical areas with high incidences of GC, as reported by Lee et al. [12]. I also aimed to investigate the causes accounting for any differences in incidence rates that were not completely explained in the previous studies.

Methods

This study is a systematic review and meta-analysis performed using data of randomized control trials (RCTs) and cohort studies according to the Cochrane [16], PRISMA [17] and MOOSE [18] guidelines. The protocol was registered in PROSPERO (Registration Number: CRD42016035345). We used Review Manager 5 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK) for the meta-analysis.

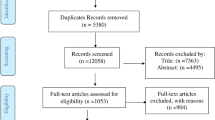

Two collaborators (TT and WT) independently searched both MEDLINE and Ichushi-Web (Japanese database for medical literature) using the terms, as shown in Fig. 1 (translation of the terms for Ichushi-Web is available in the Supplementary Materials). The search was conducted on February 20, 2017. Additional manual searches were also conducted by KS and TT to identify relevant papers, as shown in Fig. 1. The criteria for inclusion were: (1) RCTs or cohort studies published in peer-reviewed journals in English or Japanese until December 2016; (2) studies that reported the incidence rate of GC as an outcome; and (3) studies that compared eradication and control groups, including individuals either with absence of eradication therapy or failure of administered eradication therapy, or both. In studies that used chemical preventive treatment for GC in addition to eradication therapy, individuals receiving only eradication therapy were included in the eradication group. Studies that did not have any control group, targeted non-human objects, and reported only protocols (without results) were excluded. Studies including individuals who had gastric adenoma (including low-grade dysplasia), GC, or a state of being unclear at baseline (defined as first day of the follow-up period after H. pylori eradication therapy), but who had not undergone endoscopic resection or endoscopic submucosal dissection were excluded. Studies with an observation period less than 1 year were also excluded. In the case of data that was ambiguous in the original article, the corresponding author was contacted. If no response was received from the author, data from other meta-analyses were used.

Data included the sample size, number of patients who developed GC in each group, the follow-up period (mean, median, or the longest observed period), condition at baseline, and method for GC detection were extracted from selected studies. The number of participants at baseline was used as the denominator. However, the number of participants remaining at the middle or end of the follow-up periods was used if the baseline number could not be obtained. Individuals who were diagnosed with dysplasia at baseline were excluded if the literature described their subsequent development of GC. Individuals who developed GC within 1 year from baseline were excluded from the denominator. Statistical heterogeneity among studies was evaluated with I2 Higgins’s classification, which assigns thresholds of low heterogeneity, moderate heterogeneity, and high heterogeneity to I2 values of 25%, 50%, and 75%, respectively [19]. Because heterogeneity was not found to be statistically significant in the actual meta-analysis by the fixed-effects model, this model was considered appropriate and used to calculate the pooled odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI).

The incidence rate of GC varies in different countries [1] and the GC detection method and follow-up period were different across studies. The effect of the eradication therapy is reportedly affected by the condition of patients at the time of eradication [11]. Therefore, the subgroup analyses were also conducted to explore the potential heterogeneity as follows:

-

By country: Japan, Korea, China, other countries.

-

By condition at baseline: without GC, with GC.

-

By follow-up period: less than 5 years vs. 5 years or longer.

With regard to the condition at baseline, we also conducted an analysis on Japanese studies including individuals with gastritis and those with peptic ulcer, examined with endoscopy. To align the screening method, data using radiological method for screening [31] were excluded from the subgroup analyses.

Potential publication bias was assessed using funnel plot, Eggers’s test, and Begg’s test. As a sensitivity analysis, the OR was calculated excluding the studies that were identified as outliers on the funnel plot.

Results

Literature search and data extraction

The search strategy yielded 1529 potentially eligible studies from MEDLINE and 54 studies from Ichushi-Web. Twenty-eight studies [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47] from MEDLINE and no studies from Ichushi-Web were selected from the extracted studies, and four studies [48,49,50,51] were included based on the manual search. Thus, 32 studies were included in the meta-analysis (Fig. 1). Three studies did not have data on the number of participants and/or GC. Therefore, we obtained the data for two studies [35, 38] from authors and one study [41] from a published systematic review article [12].

Among the patients in the 32 studies, those diagnosed with dysplasia and indefinite dysplasia at baseline in 1 study [21], and those who developed GC within 1 year from baseline in 3 studies [30, 31, 33] were excluded. Ultimately, a total of 31,106 individuals were included in this analysis. The follow-up period ranged from 1 to 17.4 years (the longest period for a study by Take et al. [37]), and the mean age of the individuals ranged from 49.8 to 70.5.

Pooled data meta-analysis

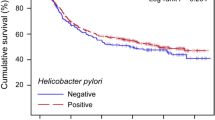

In the pooled data, 316 (1.9%) cases of GC occurred among 16,301 individuals who received H. pylori eradication therapy, and 535 (3.6%) cases of GC occurred among 14,805 individuals in the control group. The OR of GC occurrence with eradication therapy vs. control therapy was 0.46 (95% CI 0.39–0.55) based on the fixed-effects model (Fig. 2). No heterogeneity was found between the studies (I2 = 15%, p = 0.24). Uemura et al. [25] reported the lowest OR (OR 0.05, 95% CI 0.00–0.85), whereas Wong et al. [21] reported the highest OR (OR 3.28, 95% CI 0.13–81.33). As one paper utilized a radiologic screening method, we did Forest plot analysis excluding the data (supplementary Fig. 1), which showed essentially similar results (OR 0.46; 95% CI 0.38–0.54).

Subgroup analysis by countries

As only one study from Japan employed radiological method for screening, I excluded this study throughout the subgroup analyses to align detection methodology. Among all 31 studies, 16 were conducted in Japan [24,25,26,27,28,29,30, 32,33,34,35,36,37,38, 48, 49], 10 in Korea [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47, 50], 4 in China [20,21,22,23], and 1 in Colombia [51]. The subgroup of studies carried out in Japan had the lowest OR (OR 0.39; 95% CI 0.31–0.49), followed by Korea (OR 0.47; 95% CI 0.34–0.66), China (OR 0.62; 95% CI 0.42–0.91), and Colombia (OR 1.21; 95% CI 0.32–4.52) (Fig. 3a). However, the differences between countries were not statistically significant (p = 0.10). We additionally conducted a subgroup analysis for the two countries that had lower ORs (Japan and Korea), as well as one subgroup analysis for the other two countries (China and Colombia). The OR in the combined subgroup including Japan and Korea, wherein the major data represented 26 studies on the effect of eradication on GC were accumulated, was lower than that in the subgroup including China and Colombia (OR 0.39; 95% CI 0.31–0.49 vs. OR 0.62; 95% CI 0.42–0.91, p = 0.04) (forest plot data not shown).

Forest plot for the subgroup meta-analysis by a countries and b conditions at baseline with or without GC, or c with gastritis or peptic ulcer among Japanese studies. Average age for groups with or without gastric neoplasia was 64.8 ± 0.81, 52.1 ± 0.68 (mean ± standard error). Subgroup analysis by the length of follow-up (less than 5 years vs. 5 years or longer) was shown in d. All the subgroup analyses were done without including Yanaoka’s data [31], which utilized radiological method at screening. CI confidence interval, GC gastric cancer

Subgroup analysis by conditions at baseline

In 14 studies that included individuals without GC at baseline [20,21,22,23, 25, 26, 28, 30, 33, 36, 37, 39, 48, 51], subsequent GC occurred in 142 individuals (1.1%) among 12,615 who received eradication therapy and in 206 (3.0%) among 6857 control individuals. The OR comparing the eradication and control groups was 0.41 (95% CI 0.32–0.52) (Fig. 3b). In 17 studies that included individuals with GC at baseline [24, 27, 29, 32, 34, 35, 38, 40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47, 49, 50], GC developed in 169 (5.3%) among 3213 individuals who received eradication therapy and in 274 (6.4%) among 4292 individuals in the control group. The OR comparing the eradication and control groups was 0.51 (95% CI 0.40–0.64) (Fig. 3b). The test for differences between the baseline conditions was not statistically significant (p = 0.23).

Among the Japanese studies that included individuals without GC, those with gastritis and peptic ulcer were extracted and analyzed. Four studies described the number of individuals in each baseline disease and subsequent GC development. All the individuals (327 from the eradication group and 495 from the control group) in the study by Watanabe et al. [33] and a part of the individuals (207 of 404 for the eradication group and 211 of 304 for the control group) in the study by Ogura et al. [28] were included as those with gastritis at baseline. The OR comparing the eradication and control groups was 0.21 (95% CI 0.06–0.67) in this subgroup (Fig. 3c). The rest of the individuals in Ogura et al.’s study [28], and all individuals in the two studies by Mabe et al. [30] and Take et al. [37] were analyzed as those with peptic ulcer, and the OR was 0.39 (95% CI 0.21–0.70) (Fig. 3c). The OR comparing the eradication and control groups for both gastritis and peptic ulcer was 0.32 (95% CI 0.19–0.54) (Fig. 3c).

As the length of follow-up period might influence the outcome of eradication therapy, ORs between the two follow-up periods (less than 5 years vs. 5 years or longer) was analyzed. One paper [34] did not precisely describe the follow-up period, and thus was excluded from the analysis. The OR in the group with long follow-up periods was significantly lower (p = 0.01) (OR 0.32; 95% CI 0.24–0.43) than that (OR 0.55; 95% CI 0.41–0.72) of shorter follow-up group (Fig. 3d).

Quality assessment

No publication bias was found according to Egger’s test (p = 0.39) or Begg’s test (p = 0.41). However, the study by Kato et al. [35] was detected as an outlier according to the funnel plot (Supplementary Fig. 2).

A sensitivity analysis was performed excluding the study [35] that was detected as an outlier. The OR based on the pooled data meta-analysis was 0.44 (95% CI 0.37–0.52; I2 = 0%).

Relationship between incidence and mortality of GC in each country

We analyzed the incidence and mortality data of GC in 11 countries in 2012 [2, 52] to examine their relationship. Korea and Japan, countries with higher incidences of GC (41.8/100,000 and 29.9/100,000), showed lower mortality/incidence ratios (0.31 and 0.41) than the other countries, such as Taiwan (11.1/100,000 for incidence and 0.61 for mortality/incidence), France (4.7/100,000 and 0.62), and the USA (3.9/100,000 and 0.51) (Fig. 4).

Incidence and mortality/incidence of gastric cancer (age-standardized) in each region/country in 2012. Data from Taiwan Cancer Registry [52] for Taiwan and GLOBOCAN [2] for other countries were used. Incidence and mortality in Taiwan were age-standardized to world standard population in 2000 (those of other countries were age-standardized to that in 2012)

Discussion

This meta-analysis of 32 studies showed that H. pylori eradication therapy had a significant effect on reducing the incidence of subsequent GC with an OR of 0.46, although the countries, conditions at baseline, and follow-up periods varied among the studies. This result was consistent with other meta-analyses [7,8,9, 11, 12]. Thus, the present meta-analysis provided further robust evidence of the effect of eradication therapy.

Our subgroup analysis results showed that the effect of eradication therapy tended to be greater in countries with high incidences of GC, such as Japan and Korea. This finding not only corroborated with the meta-analysis that showed higher effects in the areas with higher incidence rates of GC [12], but also extended the impact of eradication to country level.

In our subanalysis based on the Japanese studies, the eradication effect tended to be higher in individuals with gastritis than those with peptic ulcer at baseline. The average age of subjects in benign conditions [52.1 ± 0.7, mean (M) ± standard error (SE)] as compared with that of patients with neoplasia (64.8 ± 0.8, M ± SE), supporting that a greater eradication effect can be expected when doing eradication therapy earlier age period preferably before irreversible changes in the mucosa occur as no beneficial effect of eradication therapy in preventing metachronous GC has been reported, particularly in individuals with IM or dysplasia [53]. Chen et al. [11] concluded in their meta-analysis that the overall reduction of GC risk was mainly attributed to preventing progression in patients with condition before IM at baseline. Transformations to malignancy may be difficult to prevent in those with IM or dysplasia. We did not compare the effect between subjects with and without IM. However, the difference in condition at baseline is one of the possible reasons for the difference in the effect of eradication among countries. Thus, inclusion of subjects with neoplastic lesions, such as dysplasia [20, 21], would have depreciated the effect of eradication on GC development. In other words, the pre-cancerous conditions or early-stage GC at baseline that had been missed in countries with inferior endoscopic methods of detecting early lesions might develop into macroscopically visible cancers during the follow-up period, resulting in higher incidence of GC after eradication therapy, as compared with Japan and Korea. Indirect support for early detection would lead to better survival [54, 55], and indeed, lower mortality/incidence ratio (Fig. 4), a surrogate marker for early curable lesions, was reported in these two countries.

An RCT published after completion of our analysis reported that patients who received eradication therapy following endoscopic resection of early GC or high-grade adenoma showed greater improvement in the grade of gastric corpus atrophy, as well as lower rates of metachronous GC than those who received placebo [56] after a long-term follow-up. Furthermore, Choi et al. recently published new data showing effectiveness in reducing gastric cancer by H. pylori eradication after a prolonged follow-up [57] and changed their previous negative conclusion on the effect of eradication in preventing metachronous gastric cancer [43]. Similar effect of follow-up period on the outcome of eradication effect was also presented in a famous trial conducted in China [22]. Our subgroup analysis showing greater risk reduction of gastric cancer in the groups with prolonged follow-up period is consistent with these reports.

This meta-analysis has several limitations. First, the data were extracted from only studies published in English or Japanese. Those written in other languages, such as Korean and Chinese, were not included. A meta-analysis including more studies written in other languages may help to build further robust evidence. Second, most of the studies conducted in Japan and Korea included more individuals with the condition before IM than those with IM or beyond. Conversely, Chinese studies included more individuals with IM or beyond than those with the condition before IM. Thus, the effects of incidence rate and condition at baseline were not comparable. When more data are available in China and other countries, another meta-analysis should be performed to examine the impact of those factors on OR. Third, the data that dealt the eradication effect in benign conditions were limited. Thus, although the effect of eradication in benign conditions numerically showed higher preventive effect as compared with that in malignant conditions, but it did not reach statistical significance requiring additional data for more robust conclusion. Nevertheless, this meta-analysis will provide a basis for estimating the magnitude of the preventive effect of eradication therapy on GC following insurance approval for H. pylori-related conditions in Japan.

In conclusion, this meta-analysis strengthens the evidence for the potential of eradication therapy to reduce the risk of GC in nations with high incidence rates of GC. Early identification of individuals with pre-cancerous gastric conditions and GC at enrollment using endoscopy might play a significant role in improving the effect of eradication therapy. This result corroborates the meta-analysis by Lee et al. [12]. However, they only described the association between the incidence of GC in specific areas (but not in entire countries) and the effect of eradication therapy, and they did not show the causality. In the present meta-analysis, we considered the difference in endoscopic techniques in the different countries and found higher incidences of GC in the areas with superior endoscopic detection of early lesions. This is exemplified by the higher survival rate of GC (namely, low mortality/incidence rate) and the number of endoscopic GC resections, which is an index of detection skill for mucosal cancers. One of the reasons for the association between the incidence of GC and the effect of eradication could be accounted for if the incidence of GC and the consequences of endoscopic examination are considered.

References

Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–86.

Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11 (Internet). Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2013. http://globocan.iarc.fr. Accessed 1 Apr 2018.

Cancer Registry and Statistics (Internet). Cancer Information Service, National Cancer Center, Japan. 2014. https://ganjoho.jp/en/professional/statistics/table. Accessed 1 Apr 2018.

Schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Lyon, 7–14 June 1994. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 1994;61:1–241.

Huang JQ, Sridhar S, Chen Y, Hunt RH. Meta-analysis of the relationship between Helicobacter pylori seropositivity and gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:1169–79.

Fuccio L, Zagari RM, Eusebi LH, Laterza L, Cennamo V, Ceroni L, et al. Meta-analysis: can Helicobacter pylori eradication treatment reduce the risk for gastric cancer? Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:121–8.

Ford AC, Forman D, Hunt RH, Yuan Y, Moayyedi P. Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy to prevent gastric cancer in healthy asymptomatic infected individuals: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2014;348:g3174.

Yoon SB, Park JM, Lim CH, Cho YK, Choi MG. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic resection of gastric tumors: a meta-analysis. Helicobacter. 2014;19:243–8.

Jung DH, Kim JH, Chung HS, Park JC, Shin SK, Lee SK, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication on the prevention of metachronous lesions after endoscopic resection of gastric neoplasm: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0124725.

Bang CS, Baik GH, Shin IS, Kim JB, Suk KT, Yoon JH, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication for prevention of metachronous recurrence after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. J Korean Med Sci. 2015;30:749–56.

Chen HN, Wang Z, Li X, Zhou ZG. Helicobacter pylori eradication cannot reduce the risk of gastric cancer in patients with intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia: evidence from a meta-analysis. Gastric Cancer. 2016;19:166–75.

Lee YC, Chiang TH, Chou CK, Tu YK, Liao WC, Wu MS, et al. Association between Helicobacter pylori eradication and gastric cancer incidence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1113–24.e5.

Doorakkers E, Lagergren J, Engstrand L, Brusselaers N. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort Studies. J Natl Cancer Inst 2016. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djw132.

Rokkas T, Rokka A, Portincasa P. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the role of Helicobacter pylori eradication in preventing gastric cancer. Ann Gastroenterol. 2017;30:414–23.

Seta T, Takahashi Y, Noguchi Y, Shikata S, Sakai T, Sakai K, et al. Effectiveness of Helicobacter pylori eradication in the prevention of primary gastric cancer in healthy asymptomatic people: a systematic review and meta-analysis comparing risk ratio with risk difference. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0183321.

Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1. 0. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. 2013.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–9.

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–12.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60.

Wong BC, Lam SK, Wong WM, Chen JS, Zheng TT, Feng RE, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication to prevent gastric cancer in a high-risk region of China: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:187–94.

Wong BC, Zhang L, Ma JL, Pan KF, Li JY, Shen L, et al. Effects of selective COX-2 inhibitor and Helicobacter pylori eradication on precancerous gastric lesions. Gut. 2012;61:812–8.

Li WQ, Ma JL, Zhang L, Brown LM, Li JY, Shen L, et al. Effects of Helicobacter pylori treatment on gastric cancer incidence and mortality in subgroups. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/dju116.

Zhou L, Lin S, Ding S, Huang X, Jin Z, Cui R, et al. Relationship of Helicobacter pylori eradication with gastric cancer and gastric mucosal histological changes: a 10-year follow-up study. Chin Med J (Engl). 2014;127:1454–8.

Uemura N, Mukai T, Okamoto S, Yamaguchi S, Mashiba H, Taniyama K, et al. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on subsequent development of cancer after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 1997;6:639–42.

Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, Matsumura N, Yamaguchi S, Yamakido M, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784–9.

Takenaka R, Okada H, Kato J, Makidono C, Hori S, Kawahara Y, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication reduced the incidence of gastric cancer, especially of the intestinal type. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:805–12.

Fukase K, Kato M, Kikuchi S, Inoue K, Uemura N, Okamoto S, et al. Effect of eradication of Helicobacter pylori on incidence of metachronous gastric carcinoma after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer: an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:392–7.

Ogura K, Hirata Y, Yanai A, Shibata W, Ohmae T, Mitsuno Y, et al. The effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on reducing the incidence of gastric cancer. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:279–83.

Shiotani A, Uedo N, Iishi H, Yoshiyuki Y, Ishii M, Manabe N, et al. Predictive factors for metachronous gastric cancer in high-risk patients after successful Helicobacter pylori eradication. Digestion. 2008;78:113–9.

Mabe K, Takahashi M, Oizumi H, Tsukuma H, Shibata A, Fukase K, et al. Does Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy for peptic ulcer prevent gastric cancer? World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4290–7.

Yanaoka K, Oka M, Ohata H, Yoshimura N, Deguchi H, Mukoubayashi C, et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori prevents cancer development in subjects with mild gastric atrophy identified by serum pepsinogen levels. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:2697–703.

Maehata Y, Nakamura S, Fujisawa K, Esaki M, Moriyama T, Asano K, et al. Long-term effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on the development of metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:39–46.

Watanabe M, Kato J, Inoue I, Yoshimura N, Yoshida T, Mukoubayashi C, et al. Development of gastric cancer in nonatrophic stomach with highly active inflammation identified by serum levels of pepsinogen and Helicobacter pylori antibody together with endoscopic rugal hyperplastic gastritis. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:2632–42.

Watari J, Moriichi K, Tanabe H, Kashima S, Nomura Y, Fujiya M, et al. Biomarkers predicting development of metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic resection: an analysis of molecular pathology of Helicobacter pylori eradication. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:2349–58.

Kato M, Nishida T, Yamamoto K, Hayashi S, Kitamura S, Yabuta T, et al. Scheduled endoscopic surveillance controls secondary cancer after curative endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer: a multicentre retrospective cohort study by Osaka University ESD study group. Gut. 2013;62:1425–32.

Shichijo S, Hirata Y, Sakitani K, Yamamoto S, Serizawa T, Niikura R, et al. Distribution of intestinal metaplasia as a predictor of gastric cancer development. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:1260–4.

Take S, Mizuno M, Ishiki K, Hamada F, Yoshida T, Yokota K, et al. Seventeen-year effects of eradicating Helicobacter pylori on the prevention of gastric cancer in patients with peptic ulcer; a prospective cohort study. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:638–44.

Ami R, Hatta W, Iijima K, Koike T, Ohkata H, Kondo Y, et al. Factors associated with metachronous gastric cancer development after endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51:494–9.

Kim N, Park RY, Cho SI, Lim SH, Lee KH, Lee W, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and development of gastric cancer in Korea: long-term follow-up. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:448–54.

Han JS, Jang JS, Choi SR, Kwon HC, Kim MC, Jeong JS, et al. A study of metachronous cancer after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:1099–104.

Seo JY, Lee DH, Cho Y, Lee DH, Oh HS, Jo HJ, et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori reduces metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2013;60:776–80.

Bae SE, Jung HY, Kang J, Park YS, Baek S, Jung JH, et al. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on metachronous recurrence after endoscopic resection of gastric neoplasm. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:60–7.

Choi J, Kim SG, Yoon H, Im JP, Kim JS, Kim WH, et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori after endoscopic resection of gastric tumors does not reduce incidence of metachronous gastric carcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:793–800e1.

Kim YI, Choi IJ, Kook MC, Cho SJ, Lee JY, Kim CG, et al. The association between Helicobacter pylori status and incidence of metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Helicobacter. 2014;19:194–201.

Kwon YH, Heo J, Lee HS, Cho CM, Jeon SW. Failure of Helicobacter pylori eradication and age are independent risk factors for recurrent neoplasia after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer in 283 patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:609–18.

Lim JH, Kim SG, Choi J, Im JP, Kim JS, Jung HC. Risk factors for synchronous or metachronous tumor development after endoscopic resection of gastric neoplasms. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:817–23.

Kim SB, Lee SH, Bae SI, Jeong YH, Sohn SH, Kim KO, et al. Association between Helicobacter pylori status and metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic resection. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:9794–802.

Kato M, Asaka M, Nakamura T, Azuma T, Tomita E, Kamoshida T, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication prevents the development of gastric cancer—results of a long-term retrospective study in Japan. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:203–6.

Nakagawa S, Asaka M, Kato M, Nakamura T, Kato C, Fujioka T, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication and metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic mucosal resection of early gastric cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:214–8.

Kim HJ, Hong SJ, Ko BM, Cho WY, Cho JY, Lee JS, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication suppresses metachronous gastric cancer and cyclooxygenase-2 expression after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Korean J Helicobacter Up Gastrointest Res. 2011;11:117–23.

Mera R, Fontham ET, Bravo LE, Bravo JC, Piazuelo MB, Camargo MC, et al. Long term follow up of patients treated for Helicobacter pylori infection. Gut. 2005;54:1536–40.

Cancer Registry Annual Report. 2012 Taiwan (in Taiwanese) (Internet) Health Promotion Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare. 2015. http://www.hpa.gov.tw/Pages/Detail.aspx?nodeid=269&pid=5190. Accessed 1 Apr 2018.

Lee YC, Chen TH, Chiu HM, Shun CT, Chiang H, Liu TY, et al. The benefit of mass eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection: a community-based study of gastric cancer prevention. Gut. 2013;62:676–82.

Cancer Statistics in Japan. 2015 (Internet). Foundation for Promotion of Cancer Research. 2015. http://ganjoho.jp/data/reg_stat/statistics/brochure/2015/cancer_statistics_2015.pdf. Accessed 1 Apr 2018.

Kaneko E, Nakamura T, Umeda N, Fujino M, Niwa H. Outcome of gastric carcinoma detected by gastric mass survey in Japan. Gut. 1977;18:626–30.

Choi IJ, Kook MC, Kim YI, Cho SJ, Lee JY, Kim CG, et al. Helicobacter pylori therapy for the prevention of metachronous gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1085–95.

Choi JM, Kim SG, Choi J, Park JY, Oh S, et al. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication for metachronous gastric cancer prevention: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;88:475–85.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Tomomi Takeshima, PhD, and Wentao Tang, PhD, employees of Milliman, for performing the literature search, developing the first draft (TT) and analyzing data (WT). The author would also like to thank Shinzo Hiroi, PhD, at the time employed by Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., for contribution to study design and interpretation of data and to Akihito Uda, Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., for coordinating this study. I would like to thank Editage (http://www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Human rights statement

This study is a meta-analysis on the published literatures and does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Informed consent

No individual patient data were used for the analysis, which should exempt this study from the requirement of obtaining informed consents.

Conflict of interest

KS has received research grants from Eisai Pharma, Daiichi Sankyo Pharma, and Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, and received lecture fees from Astellas Pharma, Fujifilm, EA Pharma, and Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. This study was funded by Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sugano, K. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on the incidence of gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastric Cancer 22, 435–445 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-018-0876-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-018-0876-0