Abstract

Background

We conducted a survey regarding irregular bowel movement in gastrectomized patients. Their defecation frequency, intestinal microflora, and intestinal environment were studied and compared with those of healthy controls.

Methods

As a first step, a questionnaire survey on bowel movement, involving 769 patients and 312 healthy controls (total: 1,081 subjects), was carried out. As a second step, the defecation frequency (scoring of the survey results conducted to evaluate the state of constipation/diarrhea), intestinal microflora, and intestinal environment were evaluated in 190 gastrectomized patients with irregular bowel movement and 31 controls identified in the first survey.

Results

First step: Of the 769 patients, 58% complained of irregular bowel movements (constipation, diarrhea, or their alternate occurrence), and their frequency of complaints was significantly higher (p < 0.01) than that in the healthy controls (33%). Second step: The levels of the most predominant obligate anaerobe and harmful bacteria in the feces were lower and higher, respectively, the fecal pH was lower, the fecal water content was lower, and the level of putrefactive metabolites in the feces was higher in the gastrectomized patients than in the healthy controls. The intestinal flora and environment were more disrupted in the totally gastrectomized than in the partially gastrectomized patients.

Conclusions

Many gastrectomized patients with irregular bowel movements exhibited significant changes showing impaired intestinal microflora and metabolite levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Advances in surgical procedures have improved the prognostic results of gastric cancer treatment [1]. However, very few effective strategies have been established to control postgastrectomy sequelae. An increasing number of patients suffer from sequelae: (1) malnutrition related to a decrease in gastric hydrochloric acid/digestive enzyme secretion and digestive hypofunction, (2) vagotomy-related reduction of digestive tract movement, (3) dumping syndrome, (4) reflux esophagitis, (5) iron-deficiency anemia, and (6) bone disorders related to calcium malabsorption [2–6]. As these disorders further reduce the digestive tract function, approximately 50% of patients who have undergone gastrectomy complain of irregular bowel movements, including diarrhea and constipation, as postoperative sequelae (unpublished data of survey of members of the ALPHA CLUB [Postgastrectomy Patients’ Association, http://alpha-club.jp/]). No study has investigated the defecation frequency or intestinal microflora/environment in a large number of patients who have undergone gastrectomy. To improve bowel movements, patients with irregular bowel movements after gastrectomy are advised to consume food containing a large amount of dietary fiber and fermented food such as yogurt.

We conducted a questionnaire survey regarding the defecation frequency in members of the ALPHA CLUB to obtain findings that would be useful for the prevention/treatment of irregular bowel movements in gastrectomized patients. Subsequently, we selected patients with abnormalities in defecation and analyzed their intestinalicroflora/environment.

Subjects, materials, and methods

Subjects and study schedule

Survey on bowel movement

A questionnaire survey regarding defecation frequency was carried out involving members of the ALPHA CLUB (Postgastrectomy Patients’ Association, http://alpha-club.jp/) (1,060 gastrectomized subjects, age 35–79 years) and their families (spouses who served as controls). Questionnaire sheets were collected from 782 gastrectomized subjects (collection rate 74%) and 404 controls (38%, subjects’ families without gastrectomy). However, responses from 769 gastrectomized subjects and 312 controls (total: 1,081 subjects) were analyzed upon the exclusion of those who had had proximal gastrectomy and 13 gastrectomized subjects (2 actually without gastrectomy, 2 who died, and 9 who did not respond to any questions) and 92 controls (no response to questions). On April 18, 2008, a questionnaire was sent to the subjects by mail. On May 15, the questionnaire collection was completed.

Survey on irregular bowel movement

From among the 1,081 participants in the above survey, the subjects in this survey were 201 gastrectomized patients and 33 controls (total 234) from whom informed consent regarding participation was obtained. Prior to this study, the study contents and methods were sufficiently explained to the subjects, and written informed consent was obtained according to the Helsinki Declaration (adopted in 1964, revised in 1975, 1983, 1989, 1996, and 2000). Entry criteria included the absence of purgatives/antidiarrheal agents taken routinely. Of the 234 subjects, 190 gastrectomized patients (121 males, 69 females, mean age 65 ± 10 years) and 31 controls (14 males, 17 females, mean age 62 ± 8 years) (total 221) were analyzed, excluding 6 who dropped out during the survey period, 1 in whom stool collection was impossible, 1 control with a history of gastrectomy, and 5 who took antimicrobial agents during the survey period.

This survey was conducted from June 19 until July 3, 2008, and from June 26 until July 10, 2008.

Examination methods

Survey by diary

Survey on bowel movement

A questionnaire survey was carried out to investigate the defecation frequency, stool features, presence or absence of current consultations at an outpatient clinic/treatment, drug therapy, frequency of yogurt/lactic acid bacteria-beverage ingestion, and postingestion bowel condition. (A questionnaire was sent to members of the ALPHA CLUB by mail to request them to respond voluntarily and cooperate with a subsequent survey.)

Survey on irregular bowel movement

The subjects recorded a diary regarding the following issue by the 24-h remembering method every day during the 2-week study period:

-

Q1 Bowel movement state (1. normal, 2. constipation, and 3. diarrhea)

-

Q2 Defecation frequency

-

Q3 Stool features (several options can be chosen. 1. round/solid, 2. solid, 3. banana-shaped, 4. semi-paste, 5. muddy, and 6. watery)

-

Q4 Condition (one option only, 1. very good, 2. good, 3. usual, 4. bad, and 5. very bad)

-

Q5 Drug name (you should write it only when taking a drug.)

-

Q6 Others (matters regarding diet/exercise may be freely written.)

We evaluated constipation and diarrhea in the subjects via the scoring of the diary results, as described below:

-

1.

Scoring of stool features

Solid stool score: [(Number of subjects selecting “round/solid” × 2) + (Number of subjects selecting “solid” × 1)]/defecation frequency

Loose stool score: [(Number of subjects selecting “watery” × 2) + (Number of subjects selecting “muddy” × 1)]/defecation frequency

-

2.

Scoring of the defecation frequency

Low frequency score: When the defecation frequency during 14 days was less than 14, differences from 14 were regarded as the score.

High frequency score: When the defecation frequency during 14 days exceeded 14, differences from 14 were regarded as the score.

-

3.

Scoring of bowel movement

Constipation score: Solid stool score × 10 + low frequency score + number of answers on “constipation” during 14 days

Diarrhea score: Loose stool score × 10 + high frequency score + number of answers on “diarrhea” during 14 days

A decrease in these scores reflects the normalization of defecation or relief of constipation/diarrhea. We established these scores as indices of constipation/diarrhea.

Stool test

Sample collection and transport

For a stool test, a stool sample was collected once during the final 3 days in week 2 of the survey on irregular bowel movement. The sample was divided into two parts, with one part placed in a tube (for microflora analysis) containing 2 ml of RNAlater (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) and the other part placed in a blank tube (for organic acid analysis, water content/pH measurement, and determination of putrefactive metabolite levels); the tubes were transported in a refrigerator to Yakult Central Institute for Microbiological Research.

Microflora test

-

1.

Fecal sampling

After a stool sample-containing tube was weighed, RNAlater (Ambion) was added at a ninefold volume to prepare a fecal suspension.

-

2.

Isolation of total RNA

For RNA stabilization, fecal homogenate (ten times dilution, 200 μl) was added to 1 ml of sterilized phosphate buffer solution (PBS), and then centrifuged at 5,000×g for 10 min. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet was stored at −80°C until it was used for the extraction of RNA. RNA [7, 8] was isolated using a method described elsewhere. Finally, the nucleic acid fraction was suspended in 1 ml of nuclease-free water (Ambion).

-

3.

Determination of the bacterial count by reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

A standard curve was generated using RT-qPCR data (using the threshold cycle [C T], the cycle number when threshold fluorescence was reached) and the corresponding cell count, which was determined microscopically by 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) staining [9] for the dilution series of the standard strains described elsewhere [7, 8]. To determine the bacteria present in samples, three serial dilutions of an extracted RNA sample were used for RT-qPCR, and the C T values in the linear range of the assay were applied to the standard curve generated in the same experiment to obtain the corresponding bacterial cell count in each nucleic acid sample and then converted to the number of bacteria per sample. The specificity of the RT-qPCR assay using group- or species-specific primers was determined as described previously [7, 8].

-

4.

Total bacterial counts

The total number of bacteria was determined by smearing a dilution of a formalin-fixed stool sample over a glass slide, staining bacteria with DAPI, detecting stained bacteria under a fluorescence microscope, and counting them using image-analysis software [9].

Measurement of the fecal concentrations of organic acids

A portion of the homogenized stool was isolated, weighed, mixed with 0.15 M perchloric acid in a fourfold volume, and reacted at 4°C for 12 h. Next, the mixture was centrifuged at 4°C and 20,400×g for 10 min, and the supernatant was filtered with a 0.45-μm membrane filter (Millipore Japan, Tokyo), and then sterilized. The concentrations of organic acids in this sample were measured using a Waters high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (Waters 432 Conductive Detector; Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA) and a Shodex Rspack KC-811 column (Showa Denko, Tokyo, Japan) [10]. We prepared a standard mixed solution consisting of 1–20 mM succinic acid, lactic acid, formic acid, acetic acid, propionic acid, isobutyric acid, butyric acid, isovaleric acid, and valeric acid, and calculated the concentrations of organic acids based on the standard curve.

Stool pH and water content

The stool pH was measured by directly inserting the glass electrode of a D-51 pH meter (Horiba Seisakusho, Tokyo, Japan) into the homogenized stool. The stool water content was calculated as the weight difference between before and after freeze-drying of a portion of the stool.

Analysis of fecal putrefactive metabolites

We measured the fecal levels of indole, ammonia, phenol, and p-cresol. A stool sample weighing approximately 2.5 g was mixed with 0.1 M PBS (pH 5.5) at 9 times the stool weight, homogenized with glass beads, and filtered with gauze. A tenfold serial dilution of this sample was used for measurement. To measure the levels of phenol and p-cresol, the sample was mixed with PBS at 9 times the stool weight, and homogenized using a stomacher (Organo, Tokyo, Japan). The stool suspension was stored at −30°C until measurement. Various putrefactive metabolites were measured, as described below. (1) Indole: a coloring reaction test was performed immediately after the dilutions were prepared. To 1.5 ml of a coloring solution prepared by dissolving 14.7 g of p-dimethyl aminobenzaldehyde in a sulfuric acid/alcohol mixture (52 ml of concentrated sulfuric acid and 948 ml of 95% ethanol) or a control coloring solution (the sulfuric acid/alcohol mixture), 0.3 ml of a 70-fold dilution of a stool sample was added. The mixture was immediately stirred, reacted at room temperature for 20 min, and centrifuged at 1,390×g for 10 min. The supernatant was placed on a microplate at 0.2 ml/well, and the absorbance at 570 nm was determined using a microplate reader (FLUO star; BMG Lab Technologies, Durham, NC, USA). As control indole solutions, 0–0.3 mM (ratio 1.5, 11 concentrations) indole solutions were prepared immediately before use. (2) Ammonia: a kit for measuring ammonia (Ammonia Test, Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Tokyo) was used. (3) Phenol and p-cresol: in a glass test tube (TST-SCR; ASAHI TECHNO GLASS, Chiba, Japan), 5 ml of a tenfold stool dilution, 2 ml of concentrated hydrochloric acid, and 0.1 ml of an internal standard solution (250 μg/ml parachlorophenol solution) were placed. The tube was sealed with a heat-proof screw cap (9998CAPH415-15; ASAHI TECHNO GLASS), and the mixture was hydrolyzed at 100°C for 60 min in an aluminum block heater (TAITEC, Saitama, Japan). It was cooled at water temperature, mixed with 4 ml of diethyl ether, agitated for 1 min for extraction, and centrifuged at 1,650×g for 10 min. The solvent layer (supernatant) at 3 ml was placed in another test tube, mixed with 3 ml of 0.05 N NaOH/methanol, and evaporated to dryness using a centrifugal concentrator (VC-360; TAITEC) and an aspirator (ASP-13; ASAHI TECHNO GLASS). The pellet was re-dissolved in 1.0 ml of distilled water, and centrifuged at 12,000×g for 20 min. The supernatant was filtered (0.45 μm), and used as an HPLC assay sample. As standard solutions, we used 0.02–6 μg/ml phenol solutions and 0.2–60 μg/ml p-cresol solutions. These solutions were assayed by HPLC using a fluorescence detector (excitation wavelength 260 nm, measuring wavelength 305 nm) and a UV detector (270 nm).

Statistical analysis

To compare the results of analysis between the two groups (gastrectomized subjects and controls), we employed the non-parametric Wilcoxon’s coded rank sum test (stool score, fecal microflora, fecal organic acids, and putrefactive metabolites) and the parametric Student’s t-test (fecal water content and pH). The results were compared among the groups using the multiple comparison test. The detection rate was analyzed using Fisher’s direct probability test. We used SPSS Ver. 11 statistical software (SPSS Japan, Tokyo, Japan). In all tests, p < 0.05 was regarded as significant.

Results

Survey on bowel movement

Incidence and type of irregular bowel movement in gastrectomized subjects and controls (with respect to age)

Of the 769 gastrectomized subjects, 58% complained of irregular bowel movement (“constipation tendency”, “diarrhea tendency”, and “repeated constipation and diarrhea”). The percentage was significantly higher than that (33%) in the controls (subjects’ families without gastrectomy) (p < 0.01, Fig. 1a, b). When dividing the irregular bowel movements in the gastrectomized subjects into the above 3 types, the proportions of subjects classified as having each type were similar, at approximately 20% (Fig. 1a). Among the gastrectomized subjects, the incidence of irregular bowel movement was the highest in those aged 30–49 years. It decreased with age (Fig. 1a). The proportions of subjects with the 3 types of irregular bowel movement differed among the age groups. However, most subjects aged 30–49 years reported “diarrhea tendency”. The interval from surgery did not influence the incidence of irregular bowel movement or the proportions of subjects with the 3 types (data not shown).

Incidence and type of irregular bowel movements in gastrectomized subjects and controls (with respect to age). a Gastrectomized subjects, b controls. Purple squares constipation tendency, green squares diarrhea tendency, yellow squares repeated constipation/diarrhea, blue squares normal, white squares no response

Of the gastrectomized subjects, 25% reported the use of purgatives. In particular, approximately 50% of those with “constipation tendency” had taken them (data not shown). Furthermore, 24% of the gastrectomized subjects had taken stomachics or digestive enzyme preparations. Among these subjects, approximately 30% of those with “constipation tendency” or “diarrhea tendency” had taken such preparations. Approximately 40% of the gastrectomized subjects had consumed yogurt or lactic acid beverages every day (data not shown).

Survey on irregular bowel movement

Comparison of the defecation state with respect to defecation symptom score-based typing in the gastrectomized subjects

In the gastrectomized subjects (n = 190), the constipation (constipation score, low solid stool score, frequency score) and diarrhea (diarrhea score, loose stool score) symptom scores were significantly higher than those in the controls (n = 31) (p < 0.05 each, Table 1).

To divide the 190 gastrectomized subjects on the basis of their symptoms, the mean constipation and diarrhea scores were calculated. Subjects with a constipation score similar to/higher than the mean were assigned to the constipation group (n = 53, group A), and those with a diarrhea score similar to/higher than the mean to the diarrhea group (n = 67, group B). Subjects in whom both constipation and diarrhea scores were similar to/higher than the means were assigned to the constipation + diarrhea group (n = 18, group C). Those in whom the two scores were below the means were assigned to the normal group (n = 52, group D). When the 190 gastrectomized subjects were divided on the basis of the type of bowel movement, subjects comprising group A, group B, and group D accounted for approximately 30% each. Those comprising group C accounted for 10%; this percentage was significantly lower (p < 0.05 each, Table 1).

Comparison of the fecal microflora, organic acid concentrations, and levels of putrefactive metabolites with respect to defecation symptom score-based typing in the gastrectomized subjects

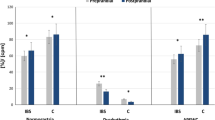

In the gastrectomized subjects, the fecal level of Clostridium leptum subgroup, a type of dominant obligate anaerobe, was lower than in the controls (p < 0.05). Furthermore, in the gastrectomized subjects, the level of Enterobacteriaceae, which is noxious, was higher than in the controls (p < 0.05). In the patients, the fecal pH was lower than in the controls (p < 0.05); in addition, the water content of stools was lower (p < 0.05). In the gastrectomized subjects, the intestinal levels of putrefactive metabolites such as ammonia and phenol were higher than those in the controls (p < 0.05). No significant differences in the intestinal microflora or environment were revealed between the bowel movement-type groups in the gastrectomized patients (Table 2).

Comparison of various measurement scores between subjects who underwent total gastrectomy and those who underwent distal partial gastrectomy

In subjects who underwent total gastrectomy, the total fecal bacterial count, dominant obligate anaerobe (C. coccoides group, C. leptum subgroup, and B. fragilis group) counts, and beneficial bacterial (Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, p < 0.05 each, Table 3) counts were lower than the counts in those who underwent partial gastrectomy. As well, the harmful bacterial (Enterobacteriaceae and C. perfringens, p < 0.05 each, Table 3) counts were greater and the intestinal microflora was more disordered in the total gastrectomy group than in the distal partial gastrectomy group. In subjects who underwent total gastrectomy, the fecal level of ammonia was higher than that in the subjects who underwent distal partial gastrectomy, suggesting disturbance of the intestinal environment (p < 0.05, Table 3).

Discussion

We conducted a large-scale survey regarding bowel movement, involving 769 gastrectomized members of the ALPHA CLUB (Postgastrectomy Patients’ Association, http://alpha-club.jp/). Approximately 60% of these subjects complained of irregular bowel movement, and the proportions of subjects with “constipation tendency”, “diarrhea tendency”, and “repeated constipation and diarrhea” were similar. This was consistent with the results of a previous questionnaire survey involving 100 gastrectomized subjects carried out by the ALPHA CLUB (unpublished data of survey for members of the ALPHA CLUB): approximately 50% complained of irregular bowel movement; and constipation tendency was noted in 22 subjects, diarrhea tendency in 13, and repeated constipation and diarrhea in 16. The present survey, carried out at an interval of more than 10 years after the previous survey, reconfirmed that most gastrectomized patients suffered from irregular bowel movement. Furthermore, the present survey initially showed that the incidence of irregular bowel movement in gastrectomized patients was higher than that in controls without gastrectomy (57 and 33%, respectively), reflecting gastrectomized patients’ serious issues regarding bowel movement. When analyzing bowel movement in gastrectomized subjects with respect to age, we found that the proportion of subjects with irregular bowel movement was higher in those aged 30–49 years than in those aged 60–79 years (83 vs. 57%, respectively). In addition, the proportions of subjects with “diarrhea tendency” and “repeated constipation and diarrhea” were higher, whereas the proportion of subjects with “constipation tendency” was lower in those aged 30–49 years, suggesting that the incidence of irregular bowel movement in gastrectomized subjects and the proportions of subjects with each type depend on age. In elderly persons, the digestive and physiological intestinal functions, as well as peristalsis, are generally reduced, sometimes leading to irregular bowel movement and subsequent symptoms even in the absence of surgical intervention [11–15]. It seemed in the present study, however, that young patients with fully restored intestinal functions were more susceptible to the influence of gastrectomy, which seemed to be an unclear cause of functional bowel disease.

To evaluate the state of constipation/diarrhea, we carried out scoring of the survey results. With respect to the types of bowel movement, the subjects were divided into 4 groups based on the constipation and diarrhea scores. In group A, consisting of gastrectomized patients, the constipation scores (constipation, hard stools, and low-frequency scores) were significantly higher than those in the healthy controls (p < 0.05 each). In group B, the diarrhea scores (diarrhea, loose stools, and high-frequency scores) were significantly higher (p < 0.05 each) than those in the healthy controls. The scoring of symptoms such as irregular bowel movements is very difficult. However, our scoring method for the defecation frequency in gastrectomized patients facilitated the evaluation of irregular bowel movements such as constipation and diarrhea in a large number of such patients.

In stool specimens from the gastrectomized subjects, the level of Clostridium leptum subgroup, a type of enteric dominant obligate anaerobe, was lower than the level in stool specimens from the healthy controls, whereas the level of Enterobacteriaceae, which is harmful, was higher, suggesting that the intestinal microflora was impaired. Shimoyama et al. [16] analyzed the fecal microflora in 74 patients who underwent surgery for gastric cancer, and reported that the enteric Bifidobacterium count was lower than that in 37 healthy adults, whereas the Enterobacteriaceae and Streptococcus (Enterococcus) counts were greater. In the present study, a similar tendency was noted: gastrectomized subjects showed a lower obligate anaerobe count and greater Enterobacteriaceae count than the healthy controls. In the gastrectomized subjects, the intestinal microflora was affected. On the other hand, when the gastrectomized subjects were divided into groups A, B, C, and D, there were no marked differences among the groups in the intestinal microflora. A previous study suggested that vagotomy- or endocrine hypofunction-related dyscoordination of the digestive tract and abnormalities in the regulation of gastrointestinal tract hormone secretion were etiologically involved in irregular bowel movements in gastrectomized patients [17]. Therefore, it was strongly suggested that, as a cause of stool abnormalities in gastrectomized patients, the involvement of such abnormal physiological functions may be rather more important than disturbances of the intestinal microflora or environment. The results shown in Table 3 revealed statistically significant differences in certain microflora even small differences. The clinical significance is uncertain as yet, although we have some clues interpreting their significance in relation to clinical symptoms. Of note, a representative probiotic, Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota, was confirmed to regulate bowel movement in healthy adults [18, 19] and reduce disturbance of the intestinal flora/environment in elderly persons [20]. Intestinal indigenous Lactobacillus and L. casei strain Shirota are different types of bacteria. Thus, L. casei strain Shirota may also be useful in gastrectomized patients.

In the present study, in the gastrectomized subjects, the intestinal levels of putrefactive metabolites such as ammonia and phenol were higher than those in the healthy controls, suggesting disturbance of the intestinal environment. Ammonia and phenol in the intestinal tract are produced by enteric bacteria via amino acid decomposition [21, 22]. The intestinal levels of these compounds are elevated with a high-protein diet ingestion-related increase in the area of the matrix utilized by enteric bacteria [23]. Therefore, in the gastrectomized subjects, gastrectomy-related digestive hypofunction may have resulted in the influx of large areas of these matrices into the large intestine, increasing the levels of ammonia and phenol. In the subjects who underwent total gastrectomy, the intestinal microflora and environment were more markedly affected in comparison with findings in subjects who underwent distal partial gastrectomy, suggesting that total gastrectomy leads to an influx of undigested food into the digestive tract, causing abnormalities.

The present survey showed that most gastrectomized patients complained of irregular bowel movements, and that their intestinal microflora/environment was impaired.

References

Adachi Y, Kitano S, Sugimachi K. Surgery for gastric cancer: 10-year experience worldwide. Gastric Cancer. 2001;4:166–74.

Matsumoto H, Masamune O, Nunode Y, Masaki K, Ohshiba S, Okada K, et al. Malabsorption after gastrectomy-effect of enzymatic preparation. Nippon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zassi. 1982;79:33–9.

Geer RJ, Richards WO, O’Dorisio TM, Woltering EO, Williams S, Rice D, et al. Efficacy of octreotide acetate in treatment of severe postgastrectomy dumping syndrome. Ann Surg. 1990;212:678–87.

Kawa Y, Seshimo A, Kameoka S. A study on gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) after distal gastrectomy. Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg. 2003;36:347–53.

Hsu-Chang CY. Bone disorder after gastrectomy—clinical & experimental studies. Nippon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1990;91:1581–90.

Pacelli F, Bossola M, Rosa F, Tortorelli AP, Papa V, Doglietto GB. Is malnutrition still a risk factor of postoperative complications in gastric cancer surgery? Clin Nutr. 2008;27:398–407.

Matsuda K, Tsuji H, Asahara T, Kado Y, Nomoto K. Sensitive quantitative detection of commensal bacteria by rRNA-targeted reverse transcription-PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:32–9.

Matsuda K, Tsuji H, Asahara T, Matsumoto K, Takada T, Nomoto K. Establishment of an analytical system for the human fecal microbiota, based on reverse transcription-quantitative PCR targeting of multicopy rRNA molecules. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:1961–9.

Jansen GJ, Wildeboer-Veloo AC, Tonk RH, Franks AH, Welling GW. Development and validation of an automated, microscopybased method for enumeration of groups of intestinal bacteria. J Microbiol Methods. 1999;37:215–21.

Kikuchi H, Yajima T. Correlation between water-holding capacity of different types of cellulose in vitro and gastrointestinal retention time in vivo of rats. J Sci Food Agric. 1992;60:139–46.

Baba T, Fuse K, Hirata M. Characteristics of Irregular bowel movement in elderly person. J Geriatric Gastroenterol. 1989;2:115–20.

Kawamura A, Kinoshita Y. Irregular bowel movement in elderly person. J Geriatric Gastroenterol. 2004;16:31–4.

Johanson JF, Sonnenberg A, Koch TR. Clinical epidemiology of chronic constipation. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1989;11:525–36.

Pilotto A, Franceschi M, Vitale D, Zaninelli A, Di Mario F, Seripa D. Rengo F; FIRI (Fondazione Italiana Ricerca sull’Invecchiamento); SOFIA Project Investigators. The prevalence of diarrhea and its association with drug use in elderly outpatients: a multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2816–23.

Lew JF, Glass RI, Gangarosa RE, Cohen IP, Bern C, Moe CL. Diarrheal deaths in the United States, 1979 through 1987. A special problem for the elderly. JAMA. 1991;265:3280–4.

Shimoyama K, Hori S, Tamura K, Yamamura M, Tanaka M, Yamazaki K. Microflora of patients with stool abnormality. Bifidobacteria Microflora. 1984;3:35–42.

Aoki T, Hanyu N. The management of the disorder after the gastric resection. Iyaku (Medicine and Drug) Journal Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan; 2000. pp. 25–35.

Matsumoto K, Takada T, Shimizu K, Kado Y, Kawakami K, Makinoet I, et al. The effects of a probiotic milk product containing Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota on the defecation frequency and the intestinal microflora of sub-optimal health state volunteers: a randomized placebo-controlled cross-over study. Biosci Microflora. 2006;25:39–48.

Matsumoto K, Takada T, Shimizu K, Moriyama K, Kawakami K, Hirano K, et al. Effects of a probiotic fermented milk beverage containing Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota on defecation frequency, intestinal microbiota, and the intestinal environment of healthy individuals with soft stools. J Biosci Bioeng. 2010;110:547–52.

Shioiri T, Yahagi K, Nakayama S, Asahara T, Yuki N, Kawakami K, et al. The effects of a synbiotic milk product containing Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota and transgalactosylated oligosaccharides on defecation frequency, intestinal microflora, organic acid concentrations, and putrefactive metabolite of sub-optimal health state volunteers: a randomized placebo-controlled cross-over study. Biosci Microflora. 2006;25:137–46.

Macfarlane GT, Cummings JH, Allison C. Protein degradation by human intestinal bacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1986;132:1647–56.

Bakke OM. Urinary simple phenols in rats fed diets containing different amounts of casein and 10 per cent tyrosine. J Nutr. 1969;98:217–21.

Cummings JH, Hill MJ, Bone ES, Branch WJ, Jenkins DJ. The effect of meat protein and dietary fiber on colonic function and metabolism. II. Bacterial metabolites in feces and urine. Am J Clin Nutr. 1979;32:2094–101.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Yakult Honsha Co., Ltd. and Yakult Central Institute for Microbiological Research for their cooperation. No financial assistance was received in support of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aoki, T., Yamaji, I., Hisamoto, T. et al. Irregular bowel movement in gastrectomized subjects: bowel habits, stool characteristics, fecal flora, and metabolites. Gastric Cancer 15, 396–404 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-011-0129-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-011-0129-y