Abstract

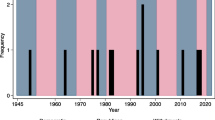

In this paper, we attempt to provide an economic explanation for the adoption of bill co-sponsorship by the US House of Representatives in 1967. We demonstrate empirically that key features of legislative production prior to 1967 (when House members’ support for a bill was indicated by introduction of duplicate bills) and post-1967 (when political support for a bill is indicated by co-sponsorship) are strikingly similar. Specifically, the raw number of supporters of a bill, whether indicated by duplicate bills or by co-sponsorship, is not nearly as critical to advancement of that bill through the House of Representatives as is the political power of the individual who introduces it and those who support it. The relative sizes of these effects are highly consistent over time. In effect, this finding means that the underlying factors of importance in the House’s legislative production function did not change significantly when bill co-sponsorship was adopted. This suggests that the change in operating procedure may have been driven by an intra-chamber struggle to control the legislative outcomes. We present empirical evidence that is highly consistent with this hypothesis—adoption of bill co-sponsorship in 1967 coincides exactly with the post-World War II peak in a concentration ratio of legislation passed in the US House of Representatives. Prior to the 90th Congress, there was a more-or-less steady increase in concentration of legislation passed by the five busiest committees that peaked at over 0.4 in the 90th Congress and then declined precipitously to under 0.15 by the 93rd Congress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Rep. William Colmer of Mississippi served on the House Rules Committee that unanimously approved limited co-sponsorship in 1967.

Because the Rules Committee agreed unanimously on this proposed change, no roll call vote of the full House membership was required or taken. In 1978 members of the US House of Representatives passed House Resolution 86, which removed the restriction on the number of bill co-sponsors.

Hence, the ith duplicate bill is not included in the calculations for mean characteristics of its counterparts in the same duplicate family. The Stata code used to generate all variables and subsequent estimates is available upon request.

OLS does not require distributional assumptions for the error component to derive coefficient estimates, whereas probit and logit require strong distributional assumptions about the disturbance to derive the estimates. Additionally, OLS will generate approximately the same average partial effects as probit and logit. Heteroskedasticity can be mitigated by using robust standard errors; however, we also control for clustering which is actually a much bigger problem of inference. We understand that for extreme values of the independent variables predicted probabilities can fall outside the unit interval. However, in our analysis we are not primarily concerned with the extreme tails of the distribution; that is, we are concerned more with how average behavior is changing across two different institutional settings. See Wooldridge (2010, pp. 563). We also estimate the same models using probit and logit. The average partial effects for logit and probit were not significantly different form the marginal effects reported for OLS. These results are available upon request.

Though 29 years in the House of Representatives is uncommon, this statement clarifies the extent to which seniority has an effect on bills being reported out of the committee.

These results are available upon request.

The Legislative Reorganization Act of 1946 had expanded the jurisdiction of standing committees and as a result increased the political influence of the committee chairs (Kravitz 1990).

This really was an intra-party fight between members of the Democratic Party, which enjoyed a roughly 2-1 majority in the House of Representatives during the 1960s. Of course, many of these individuals were Southern Democrats—conservative in philosophy rather than liberal.

The formation in 1965 of the Joint Committee on the Organization of the Congress eventually resulted in the Legislative Reorganization Act of 1970.

The context of this statement must be taken into consideration to understand its implications. Joseph G. Cannon has long been looked at as a strong handed ruler during his tenure as Speaker of the House. However, Mr. Cannon was not a preference outlier when he assumed control of the house (Krehbiel and Wiseman 2001). Further, his response to criticism of ruling with czar-like power cited that the majority of the House stood behind his actions. Upon the “revolt”, Cannon vacated his seat as the House Chair, but was subsequently reinstated, showing that the majority still stood behind his leadership. These notions seem to suggest that this was more of a reformation of Cannon’s power, rather than a revolt against his control.

References

Akerlof GA (1983) Loyalty filters. Am Econ Rev 73(1):54–65

Bernhard W, Sulkin T (2013) Commitment and consequences: reneging on cosponsorship pledges in the U.S. House. Legis Stud Q 38(4):461–487

Browne WP (1985) Multiple sponsorship and bill success in U.S. state legislatures. Legis Stud Q 10(4):483–488

Burkett T (1997) Cosponsorship in the United States Senate: a network analysis of Senate communication and leadership, 1973–1990. Ph.D. dissertation, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC

Campbell JE (1982) Cosponsoring legislation in the U.S. Congress. Legis Stud Q VII(3):415–422

Colmer W (1967) Congressional Record: 10710

Cook J (2000) Cosponsorship and the United States Congress. CongressWatch

Cox GW, McCubbins MD (2005) Setting the agenda: responsible party government in the US House of representatives. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Crain WM, Leavens DR, Tollison RD (1986) Final voting in legislatures. Am Econ Rev 76(4):833–841

Crain WM, Tollison RD (1980) The sizes of majorities. South Econ J 46:726–734

Crain WM, Tollison RD (1982) Team production in political majorities. Micropolitics 2:111–121

Fowler JH (2006a) Legislative cosponsorship networks in the US House and Senate. Soc Netw 28:454–465

Fowler JH (2006b) Connecting the Congress: a study of cosponsorship networks. Polit Anal 14:456–487

Haeberle SH (1978) The institutionalization of the subcommittee in the United States House of Representatives. J Polit 40(4):1054–1065

Harward BM, Moffett KW (2010) The calculus of cosponsorship in the U.S. Senate. Legis Stud Q 35(1):117–143

Highton B, Rocca MS (2005) Beyond the roll-call arena: The determinants of position taking in congress. Polit Res Q 58(2):303–316

Kessler D, Krehbiel K (1996) Dynamics of cosponsorship. Am Polit Sci Rev 90(3):555–566

Koger G (2003) Position taking and cosponsorship in the US House. Legis Stud Q 28(2):225–246

Kravitz W (1990) The advent of the modern Congress: the legislative reorganization Act of 1970. Legis Stud Q 15(3):375–399

Krehbiel K (1995) Cosponsors and Wafflers from A to Z. Am J Polit Sci 39:906–923

Krehbiel K, Wiseman A (2001) Joseph G. Cannon: Majoritarian from Illinois. Legis Stud Q 26(3):357–389

Krutz GS (2005) Issue and institutions: ‘Winnowing’ in the U.S. Congress. Am J Polit Sci 49(2):313–326

Leibowitz AA, Tollison RD (1980) A theory of legislative organization: making the most of your majority. Q J Econ 94:261–277

Purpura S, Wilkerson J, Hillard D (2008) The U.S. policy agenda legislation corpus volume I—a language resource from 1947–1998. http://crow.ee.washington.edu/~hillard/PurpuraWilkersonHillardLREC2008.pdf

Rohde DW (1991) Parties and leaders in the post reform House. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Tanger SM, Laband DN (2009) An empirical analysis of bill co-sponsorship in the U.S. Senate: the Tree Act of 2007. For Policy Econ 11(4):260–265

Tanger SM, Seals RA, Laband DN (2012) Does bill co-sponsorship affect campaign contributions? Evidence from the U.S. House of Representatives, 2000–2008. working paper, Auburn University

Thomas S, Grofman B (1993) The effects of congressional rules about bill cosponsorship on duplicate bills: changing incentives for credit claiming. Public Choice 75:93–98

Thomas S, Grofman B (1992) Determinents of legislative success in House committees. Public Choice 74:233–243

Volden C, Wiseman AE (2009) Legislative effectiveness in Congress. Manuscript presented at the 2009 Annual meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association

Volden C, Wiseman AE, Wittmer DE (2013) When are women more effective lawmakers than men? Am J Polit Sci 57(2):326–341

Wilson RK, Young CD (1997) Cosponsorship in the United States Congress. Legis Stud Q 22(1):25–43

Wooldridge JeffreyM (2010) Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data, 2nd edn. MIT Press, Cambridge

Zhang Y, Friend AJ, Traud AL, Porter MA, Fowler JH, Mucha PJ (2008) Community structure in congressional cosponsorship networks. Phys A 387(7):1705–1712

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We received helpful comments from our colleagues John Sophocleus, Michael Stern, Randy Beard, and from colleagues who attended a brownbag lunch seminar hosted by the School of Public Policy at Georgia Tech. We did not solicit co-sponsors. While duplicate versions of this paper might indicate support for the scientific contribution we present, they most assuredly would not be appreciated by the authors of this paper. We are solely responsible for any errors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Laband, D.N., Seals, R.A. & Wilbrandt, E.J. On the importance of inequality in politics: duplicate bills and bill co-sponsorship in the US House of Representatives. Econ Gov 16, 353–378 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10101-015-0170-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10101-015-0170-0