Abstract

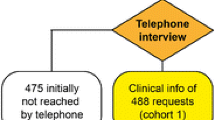

Two-tier serology is often used to confirm a diagnosis of Lyme disease. One hundred and four patients with physician diagnosed erythema migrans rashes had blood samples taken before and after 3 weeks of doxycycline treatment for early Lyme disease. Acute and convalescent serologies for Borrelia burgdorferi were interpreted according to the 2-tier antibody testing criteria proposed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Serostatus was compared across several clinical and demographic variables both pre- and post-treatment. Forty-one patients (39.4 %) were seronegative both before and after treatment. The majority of seropositive individuals on both acute and convalescent serology had a positive IgM western blot and a negative IgG western blot. IgG seroconversion on western blot was infrequent. Among the baseline variables included in the analysis, disseminated lesions (p < 0.0001), a longer duration of illness (p < 0.0001), and a higher number of reported symptoms (p = 0.004) were highly significantly associated with positive final serostatus, while male sex (p = 0.05) was borderline significant. This variability, and the lack of seroconversion in a subset of patients, highlights the limitations of using serology alone in identifying early Lyme disease. Furthermore, these findings underline the difficulty for rheumatologists in identifying a prior exposure to Lyme disease in caring for patients with medically unexplained symptoms or fibromyalgia-like syndromes.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013) Notice to readers: final 2012 reports of nationally notifiable infectious diseases. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 62:669–682

Bacon R, Kugeler K, Mead P (2008) Surveillance for lyme disease—United States, 1992–2006. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 57:1–9

Steere AC (2001) Lyme disease. N Engl J Med 345:115–125. doi:10.1056/NEJM200107123450207

Wormser GP, Nowakowski J, Nadelman RB et al (2008) Impact of clinical variables on Borrelia burgdorferi-specific antibody seropositivity in acute-phase sera from patients in North America with culture-confirmed early Lyme disease. Clin Vaccine Immunol 15:1519–1522. doi:10.1128/CVI.00109-08

Dinerman H, Steere AC (1992) Lyme disease associated with fibromyalgia. Ann Intern Med 117:281–285

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1995) Recommendations for test performance and interpretation from the Second National Conference on Serologic Diagnosis of Lyme Disease. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 44:590–591

Aguero-Rosenfeld ME, Nowakowski J, Bittker S et al (1996) Evolution of the serologic response to Borrelia burgdorferi in treated patients with culture-confirmed erythema migrans. J Clin Microbiol 34:1–9

Kalish RA, McHugh G, Granquist J et al (2001) Persistence of immunoglobulin M or Immunoglobulin G Antibody responses to Borrelia Burgdorferi 10–20 years after active Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis 33:780–785. doi:10.1086/322669

Aberer E, Schwantzer G (2012) Course of antibody response in Lyme Borreliosis patients before and after therapy. ISRN Immunol 2012:1–4. doi:10.5402/2012/719821

Schwarzwalder A, Schneider M (2010) Sex differences in the clinical and serologic presentation of early lyme disease: results from a retrospective review. Gend Med 7:320–329. doi:10.1016/j.genm.2010.08.002

Jarefors S, Bennet L, You E et al (2006) Lyme borreliosis reinfection: might it be explained by a gender difference in immune response? Immunology 118:224–232. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02360.x

Aucott J, Seifter A, Rebman A (2012) Probable late lyme disease: a variant manifestation of untreated Borrelia burgdorferi infection. BMC Infect Dis 12:173. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-12-173

Strle F, Wormser GP, Mead P, Dhaduvai K (2013) Gender disparity between cutaneous and non-cutaneous manifestations of Lyme Borreliosis. PLoS One 8:e64110. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0064110

Bennet L, Stjernberg L, Berglund J (2007) Effect of gender on clinical and epidemiologic features of Lyme borreliosis. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 7:34–41

Kuehn BM (2013) CDC estimates 300,000 US cases of Lyme disease annually. J Am Med Assoc 310:1110. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.278331

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Lyme Disease Research Foundation. The authors would like to thank Eric Weinstein for assistance with the manuscript and figures.

Disclosures

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rebman, A.W., Crowder, L.A., Kirkpatrick, A. et al. Characteristics of seroconversion and implications for diagnosis of post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome: acute and convalescent serology among a prospective cohort of early Lyme disease patients. Clin Rheumatol 34, 585–589 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-014-2706-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-014-2706-z