Abstract

This paper attempts to reconcile two strands of literature on oil and speculation: one that posits the predominance of supply/demand fundamentals, and one that investigates the hypothesis of speculative trading. To do so, we develop a Markov switching analysis based on the WTI crude oil futures price, CFTC disaggregated data, and fundamentals of the oil price. The benefits of this approach are twofold: (1) the model is able to track changes in the underlying business cycle, and (2) the model explicitly incorporates data on the net positions of money managers as a proxy for speculative activity. After verifying the sensitivity of our results to the inclusion of supply and demand factors on the oil market, we cannot eliminate statistically the possibility of speculation among the main reasons behind the 2008 oil price swing. We also explicitly recognize the influence of many other economic variables during that specific time period.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Note that the futures data are probably an underestimate, since they do not include options or over-the-counter trades. Furthermore, it is important to note that major oil producers, like Saudi Arabia and the other OPEC countries, deal only in the spot market and not in the futures market.

So far, futures exchanges themselves, principally NYMEX, have been allowed to set their own limits.

Processors and merchants include traditional commercial users, processors and producers of the commodity who are actively engaged in the physical markets, and are using the futures to hedge the associated price risk.

Swap dealers are traders who deal primarily in swaps and hedge those transactions in the futures markets. A large portion of swap dealers’ trading represents commodity index investors and swap dealer positions are often used as a proxy for their activity.

Other reportable agents might include large individual speculative traders or market-makers, as well as firms managing their own assets.

Notably, a substantial portion of passive investors are known to gain desired exposures to commodities markets through swap dealers.

The short-run price elasticity of demand is estimated to be less than −0.1 and the long-run price elasticity ranges between −0.2 and −0.3 (Hamilton 2009a).

Total OPEC production rose steadily month by month from January through July 2008, and average daily production during these seven months was about 4 percent above the average daily production in 2007.

These results are not reported here to conserve space, and may be obtained upon request.

Usual unit root tests results (ADF, PP, KPSS) are not reproduced to conserve space, and may be obtained upon request.

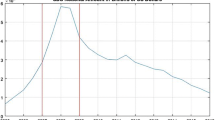

This estimation routine generates two by-products in the form of the regime and smoothed probabilities. Recall that the regime probability at time t is the probability that state t will operate at t, conditional on the information available upto t − 1. The other by-product is the smoothed probability, which is the probability of a particular state in operation at time t conditional on all information in the sample. The smooth probability allows the researcher to 'look back', and observe how regimes have evolved overtime (Fong and See 2002). Since both plots are similar, we only reproduce the smooth probability in the paper to conserve space.

More details about the distributional characteristics for the Morkov-switching process, and further diagnostic tests regarding the symmetry of the Markov transition matrix and the simple nested null hypothesis that the data follow a geometric random walk with i.i.d. innovations may be obtained upon request to the authors.

Note that we obtain qualitatively similar results by using the OPEC's crude oil and liquid fuels supply variable.

Since this period, OPEC spare capacity has continuously risen: it has more than quadrupled by April 2009, largely due to the global economic downturn and steadily weaker demand.

The S&P GSCI is one of the most widely tracked commodity indexes, and generally considered an industry benchmark. It is computed as a production-weighted average of the prices from 24 commodity futures markets with a relatively heavy weighting towards energy markets (Irwin and Sanders 2012).

Recall that the smooth probability is the probability of a particular state in operation at time t conditional on all information in the sample. It allows the researcher to ‘look back’, and observe how regimes have evolved over time.

References

Ahn D (2009) Speculation and commodity prices: anatomy of a quasi-bubble from 2006 to 2008. Report, Lehman Brothers, USA

Ang A, Bekaert G (2002) Regime switches in interest rates. J Bus Econ Statist 20(2):163–182

Bradley MD, Jansen DW (2004) Forecasting with a nonlinear dynamic model of stock returns and industrial production. Int J Forecast 20(2):321–342

Büyükşahin B, Harris JH (2011) Do speculators drive crude oil futures prices? Energy J 32(2):167–202

Caballero R, Farhi E, Gourinchas P (2008) Financial crash, commodity prices and global imbalances. Brookings Pap Econ Act 2:1–55

Chan KF, Treepongkaruna S, Brooks R, Gray S (2011) Asset market linkages: evidence from financial, commodity and real estate assets. J Bank Finance 35(6):1415–1426

Cifarelli G, Paladino G (2010) Oil price dynamics and speculation: a multivariate financial approach. Energy Econ 32(2):363–372

Clements MP, Krolzig HM (2002) Can oil shocks explain asymmetries in the us business cycle? Empirical Econ 27(2):185–204

Engemann KM, Kliesen KL, Owyang MT (2011) Do oil shocks drive business cycles? Some US and International Evidence. Macroecon Dynam 15(S3):498–517

Fan Y, Xu JH (2011) What has driven oil prices since 2000? A structural change perspective. Energy Econ 33:1082–1094

Fattouh B (2010) The dynamics of crude oil price differentials. Energy Econ 32(2):334–342

Fong WM, See KH (2002) A Markov switching model of the conditional volatility of crude oil futures prices. Energy Econ 24:71–95

Franses PH, van Dijk D (2003) Non-linear time series models in empirical finance, 2nd edn. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Guidolin M, Timmermann A (2006) An econometric model of nonlinear dynamics in the joint distribution of stock and bond returns. J Appl Econom 21(1):1–22

Greene WH (2003) Econometric analysis, 5th edn. Prentice Hall, New Jersey

Hamilton JD (1983) Oil and the macroeconomy since World War II. J Political Econ 91(2):228–248

Hamilton JD (1989) A new approach to the economic analysis of non-stationary time series and the business cycle. Econometrica 57:357–384

Hamilton JD (1996) This is what happened to the oil-price macroeconomy relationship. J Monet Econ 38(2):215–220

Hamilton JD (2008) Regime-switching models. In: Durlauf SN, Blume LE (eds) The new palgrave dictionary of economics, 2nd edn. Palgrave Macmillan, New York, pp 1–15

Hamilton JD (2009a) Understanding crude oil prices. Energy J 30(2):179–206

Hamilton JD (2009b) Causes and consequences of the oil shock of 2007–08. Brookings Pap Econ Act 1:215–261

Hamilton JD (2011) Nonlinearities and the macroeconomic effects of oil prices. Macroecon Dynam 15(S3):364–378

He LY, Fan Y, Wei YM (2009) Impact of speculator’s expectations of returns and time scales of investment on crude oil price behaviors. Energy Econ 31:77–84

Herrera AM, Lagalo LG, Wada T (2011) Oil price shocks and industrial production: is the relationship linear? Macroecon Dynam 15(S3):472–497

Irwin SH, Sanders DR (2012) Testing the Masters hypothesis in commodity futures markets. Energy Econ 34:256–269

Khan MS (2009) The 2008 oil price bubble. Policy Brief #PB09-19, Peterson Institute for International Economics, Washington, DC, USA

Kaufmann RK, Ullman B (2009) Oil prices, speculation, and fundamentals: interpreting causal relations among spot and futures prices. Energy Econ 31:550–558

Kilian L (2009) Not all oil price shocks are alike: disentangling demand and supply shocks in the crude oil market. Amer Econ Rev 99(3):1053–1069

Kilian L (2010) Explaining fluctuations in gasoline prices: a joint model of the global crude oil market and the US retail gasoline market. Energy J 31(2):105–130

Kilian L, Hicks B (2012) Did unexpectedly strong economic growth cause the oil price shock of 2003–2008? J Forecasting (forthcoming)

Kilian L, Murphy D (2010) The role of inventories and speculative trading in the global market for crude oil. CEPR Discussion Paper No. 7753, London

Kilian L, Vigfusson RJ (2011) Nonlinearities in the oil price-output relationship. Macroecon Dynam 15(S3):337–363

Krolzig HM (1997) Markov Switching vector autoregressions: modelling, Statistical Inference and Application to Business Cycle Analysis. Springer, Berlin

Kumar S, Managi S, Matsuda A (2012) Stock prices of clean energy firms, oil and carbon markets: a vector autoregressive analysis. Energy Econ 34(1):215–226

Medlock KB III, Jaffe AM (2009) Who is in the oil futures market and how has it changed?. Baker Institute Study, Rice University, USA

Parsons JE (2010) Black gold & fool’s gold: speculation in the oil futures market. Economia 10(2):81–116

Raymond JE, Rich RW (1997) Oil and the macroeconomy: a markov state-switching approach. J Money Credit Banking 29(2):193–213

Ribeiro R, Eagles L, Von Solodkoff N (2009) Commodity prices and futures positions. Research Note, Morgan JP; Global Asset Allocation & Alternative Investments

Sanders DR, Irwin SH, Merrin RP (2009) The adequacy of speculation in agricultural futures markets: too much of a good thing? Research Report 2008–02, University of Illinois, Illinois

Saporta V, Trott M, Tudela M (2009) What can be said about the rise and fall in oil prices? Bank Engl Q Bull 49(3):215–225

Sornette D, Woodard R, Zhou WX (2009) The 2006–2008 oil bubble: evidence of speculation, and prediction. Physica A: Statis Mech Appl 388(8):1571–1576

Taylor SJ (2008) Modelling financial time series, 2nd edn. World Scientific Publishing, London

Tang K, Xiong W (2010) Index investing and the financialization of commodities. NBER Working Paper #16385, USA

Till H (2009) Has there been excessive speculation in the us oil futures markets? What can we (carefully) conclude from new cftc data? Working Paper. EDHEC Risk Institute

Working H (1960) Speculation on hedging markets. Stanford University Food Research Institute Studies 1(2):185–220

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank for fruitful discussions anonymous referees and the Editor Prof. Shunsuke Managi, as well as Jean-Marie Chevalier, Michel Laffitte and the Members of the Working Group on the Volatility of Oil Prices—Frederic Baule, Frederic Lasserre, Ivan Odonnat, Edouard Viellefond—of which the Report Chevalier (2010) has been submitted to Christine Lagarde, French Minister of Economics, Industry and Employment on February 9, 2010. The author wishes to thank also the experts consulted during the preparation of the report at the IEA, the CFTC, the US Treasury, the US Department of State, the Federal Reserve, the EIA, the Congressional Research Service, the US Senate, the US Department of Energy, the CSIS, PFC Energy, the World Bank, the IMF, Deutsche Bank (Washington, DC USA) and the European Commission (DG MARKT, DG ECFIN, DG TREN (Brussels)): Didier Houssin, David Fyfe, Jacqueline Hamra Mesa, Robert Rosenfeld, Eric Juzenas, James Moser, Nela Richardson, Stephen Sherrod, Rafael Martinez, Gregory Kuserk, Jordon Grimm, Sandra Cvitan, Douglas Hengel, Roger Diwan, Trevor Reeve, Patricia White, Howard Gruenspecht, Bob Ryan, Robert Pirog, Rena Miller, Cory Claussen, Patrick McCarty, Mark Jickling, Carmen Difiglio, Guy Caruso, Adam Sieminski, George Kramer, Thomas Helbling, Matthew Jones, Randall Dodd, Ana Fiorella Carvajal, Paulo de Sa, Shane Streifel, Masami Kojima, Robert Bacon, Jean−Christophe Donnellier, Christophe Destais, Maxime Schenckery, Cameron Griffith, Jean−Guillaume Poulain, Roland Lhomme, Hannes Huhtaniemi, Alexandre Mathis, Peer Ritter, Joan Canton, Asa Johannesson Linden, Jan Panek, Eero Ailio, Klaus−Dietman Jacobi, Marcus Lippold, Malcolm Mcdowell, Zslot Tasnadi, Adam Szolyak. All errors and omissions remain by the author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Chevallier, J. Price relationships in crude oil futures: new evidence from CFTC disaggregated data. Environ Econ Policy Stud 15, 133–170 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10018-012-0045-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10018-012-0045-3