Abstract

A new aquareovirus was isolated from cultured Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus) fry at a facility where massive mortalities had occurred during the start-feeding phase. The same virus was also detected in juveniles (about 10 grams) of the 2013 generation at two other production sites, but not in larger fish from generations 2007–2012. The virus replicated in BF-2 and CHSE-214 cell cultures and produced syncytia and plaque-like cytopathic effects. This Atlantic halibut reovirus (AHRV) was associated with necrosis of the liver and pancreas, syncytium formation in these tissues, and distinct viroplasm areas within the syncytium in halibut fry. Transmission electron microscopy revealed that the viroplasm contained virions, non-enveloped, icosahedral particles approximately 70 nm in diameter with a double capsid layer, amorphous material, and tubular structures. The RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) gene from the AHRV isolates showed the highest amino acid sequence identity (80 %) to an isolate belonging to the species Aquareovirus A, Atlantic salmon reovirus TS (ASRV-TS). A partial sequence from the putative fusion-associated small transmembrane (FAST) protein of AHRV was obtained, and this sequence showed the highest amino acid sequence identity (46.8 %) to Green River Chinook virus which is an unassigned member of the genus Aquareovirus, while a comparison with isolates belonging to the species Aquareovirus A showed <33 % identity. A proper assessment of the relationship of AHRV to all members of the genus Aquareovirus, however, is hampered by the absence of genetic data from members of several Aquareovirus species. AHRV is the first aquareovirus isolated from a marine coldwater fish species and the second reovirus detected in farmed fish in Norway. A similar disease of halibut fry, as described in this paper, has also been described in halibut production facilities in Canada and Scotland.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus) production in Norway is limited to a few broodfish sites delivering fish to a small number of marine production sites. The dominating disease problems during the last 10 years have been related to Atlantic halibut nervous necrosis virus (AHNNV), infectious pancreatic necrosis virus (IPNV), and bacterial infections caused by Aeromonas sp and Vibrio spp. [1–5]. At some sites, mortality has been associated with liver necrosis with unknown aetiology [4]. Similar liver pathology has also been described in captive juvenile Atlantic halibut in Atlantic Canada [6]. The authors of that study concluded that the pathology was a result of an aquareovirus infection, and they found acute necrosis of proximal renal tubules in addition to the liver pathology. The fish were also infected with bacteria, but the causative agent of the disease and the observed mortality was believed to be of viral origin. A reovirus-like hepatitis in post-weaned farmed Atlantic halibut resulting in a mortality rate exceeding 95 % has also been described in Scotland [7]. However, none of these studies including sequencing of parts of the viral genome from the infected halibut, leaving the question about the virus identity open.

In 2013, we received material from a population of farmed Atlantic halibut that had experienced a high rate of mortality during weaning. The histopathology showed a resemblance to that described by Cusack et al. [6] and Ferguson et al. [7]. Transmission electron microscopy revealed the presence of virus-like particles with morphology similar to that of members of the family Reoviridae. Several members of this family have been isolated from fish, and the majority belong to the genus Aquareovirus [8, 9]. Aquareoviruses have been isolated from finfish and crustaceans and resemble the orthoreoviruses, but they possess 11 dsRNA genome segments and have a genome size of about 23 kbp. Aquareovirus particles are non-enveloped, spherical, multiple shelled, and about 80 nm in diameter. A typical cytopathic effect in cell culture is the production of large syncytia [10].

The aim of this study was to identify the virus associated with the high mortality of Atlantic halibut larvae at a hatchery in Norway, describe the histopathology in infected fish, and characterize the possible causative agent.

Materials and methods

A high mortality rate was observed in juveniles of Atlantic halibut, Hippoglossus hippoglossus, that were kept in a commercial hatchery at 12 °C (80–90 % mortality), starting about 40 days after start-feeding (90–100 days after fertilization). The larvae were fed enriched Artemia but stopped eating prior to the onset of mortality. Moribund and dead larvae were removed daily from the affected tanks. Moribund larvae were collected from the rearing tanks and transported to the Fish Disease Research Laboratory at the University of Bergen in May 2013, where fish from three different tanks were processed for histology and histopathology (n = 14), and later transmission electron microscopy (n = 1). Five of the fish that were received, from two of the tanks experiencing mortality, were homogenized, sterile filtered (0.2 µm), and inoculated onto a selection of different cell cultures for virus isolation. Lastly, 10 larvae from the same two tanks were used for RNA extraction and downstream real-time RT-PCR. Water samples from the main sea water intake, and before and after the brood fish tanks, were filtered, RNA was extracted as described by Andersen et al. [11], and Artemia used as feed were sampled for real-time RT PCR analysis.

In addition to this first batch of fish, 79 larvae from both affected and unaffected tanks were stored at −80 °C until RNA extraction. Lastly, in order to examine whether the virus was present in older fish, 63 halibut of different generations (2007–2013, between 5 and 15 fish per generation) were collected from four different production sites in western Norway. Gill, liver, kidney and brain tissues from these individuals were stored at −80 °C until RNA extraction, and liver (n = 63) and kidney (n = 43) samples were used for real-time RT-PCR screening.

Histology

The larvae were cut in two and fixed by immersion in a modified Karnovsky fixative in which the distilled water had been replaced by a Ringers solution. The fixative contained 4 % sucrose. Before embedding in EMBED-812 (Electron Microscopy Sciences), the tissues were stained/post-fixed in 2 % OsO4 for 60 minutes. Semi- and ultrathin sections were cut on a Reichert-Jung Ultracut E. The ultrathin sections (about 30 nm) were stained for 90 minutes in a 2 % aqueous uranyl acetate solution, followed by lead citrate. Semithin sections, 1.0 µm, were stained with toluidine blue. The semi- and ultrathin sections were used for examination of tissue changes and the possible presence of pathogens.

Cell cultures

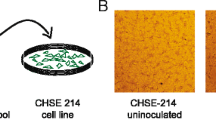

Histology and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) revealed the presence of reovirus- like particles in the liver and pancreas of the halibut larvae. The following cell cultures were tested as possible culture systems for these reovirus-like particles: BF2 cells (ATCC no. CCL-91), CHSE-214 cells (ATCC no. CRL-1681), RTgill cells, and ASK cells [12–15]. The cells were cultured in 75-cm2 tissue culture flasks at 20 °C in Eagle’s minimum essential medium (EMEM) supplemented with foetal bovine serum (10 %), L-glutamine (2 mM), non-essential amino acids (1 %), HEPES (10 mM) and gentamicin (20 μg ml−1). The cells were subcultured biweekly and formed monolayers within 2-7 days.

An aquareovirus, termed Atlantic halibut reovirus (AHRV), was isolated from the Atlantic halibut larvae collected from the two tanks with high mortality during start-feeding. For virus propagation, cell culture medium was removed from cell monolayers, cells were washed with PBS (pH 7.3), and sterile-filtered homogenate from the halibut larvae, diluted in serum-depleted medium (2 % FBS, L-glutamine, non-essential amino acids, HEPES, gentamicin), was added and allowed to adsorb for 90 minutes. The cells were incubated at 15 °C for 4–5 weeks, or until cytopathic effect (CPE) was observed. For all virus isolation procedures, a negative control of each cell culture type used was included and treated similarly to the infected cells.

RNA extractions

The extraction of RNA from the halibut, artemia, and cell cultures were done as described by Devold et al. [12]. The RNA samples were stored at −20 °C.

RT-PCR, sequencing and real-time RT-PCR

Primers targeting conserved areas in segments two and seven from chum salmon reovirus (accession nos. AF418295 and AF418300), Atlantic salmon reovirus (Accession nos. EF434978 and FJ652575) and a turbot aquareovirus (accession nos. HM989931 and HM989936) were constructed (Table 1). All PCR products were processed using ExoSAP-IT® reagent (Affymetrix®) and sequenced using a BigDye Terminator Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems). Sequencing was done on PCR products, and all products were sequenced at least twice. Sequencing was performed at the sequencing facility at the University of Bergen (http://seqlab.uib.no/).

The partial sequences of a segment believed to be the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) gene from two Atlantic halibut reovirus isolates, AHRV241013 and AHRV060513, have been deposited in the GenBank database under the accession numbers KJ499467 and KJ499468, respectively. The accession number for the partial sequence of a possible FAST protein gene from AHRV060513 is KJ913664.

Based on the partial sequence from the putative FAST protein gene (Segment 7) a TaqMan real-time RT-PCR assay was developed (Table 2). This assay was used in all testing of the RNA from halibut tissues and cell cultures inoculated with homogenates from the moribund halibut larvae. The RNA from the tissues of the halibut juveniles was also tested for the presence of Atlantic halibut nervous necrosis virus (AHNNV) and infectious pancreatic necrosis virus (IPNV) using TaqMan real-time RT-PCR assays [16, 17]. During the real-time RT-PCR screening, a housekeeping gene, elongation factor 1 alpha (EF1A1), was used as an internal control [18].

Phylogeny

Sequence data were analyzed and assembled using VectorNTI software. The partial amino acid sequences of the putative RdRp and FAST proteins from AHRV were aligned with homologous protein sequences from selected reoviruses already available in the EMBL nucleotide database. To perform pairwise comparisons between the different virus proteins, the multiple sequence alignment editor GeneDoc (available at http://www.psc.edu/biomed/genedoc) was used. Polymorphic regions were aligned manually.

Phylogenetic analysis of the alignment of the putative RdRp was performed using the software TREE-PUZZLE 5.2 with maximum likelihood (ML) as optimality criterion, and the VT matrix for amino acid substitution. Bootstrapping of ML trees was done by 1000 quartet puzzling (QP) steps. Phylogenetic trees were drawn using TreeView [19].

Results

The production site for halibut larvae had repeatedly been losing larvae during start-feeding and through the weaning phase for the last two years. The mortality rate ranged from 80 to 90 % in the different production tanks. During the period when mortality was observed, the larvae stopped eating, became passive, showing no escape behaviour, and died after a few days. The affected larvae were all positive for the presence of a member of the aquareoviruses (here named Atlantic halibut reovirus, AHRV), and negative for the presence of nervous necrosis virus (NNV) and infectious pancreas necrosis virus (IPNV). The Ct values obtained from this initial batch (n = 10), using the AHRV-7 real-time RT-PCR assay, ranged from 17.8 to 22.1. No parasites or bacteria were observed during the microscopic examination of the moribund larvae. The sea water intake and the artemia used as feed were negative for the presence of AHRV.

Of the 79 larvae received after the initial batch, 32 were from tanks with a high mortality rate (3 different tanks), and 31 of these were positive for the Atlantic halibut reovirus by real time RT-PCR screening (Ct values 18.6–28.9). Twenty-seven larvae came from a tank with halibut showing abnormal behaviour and were sampled twice, only a few days apart (n = 6 followed by n = 21). The Ct values obtained for this tank ranged from 20 to 37, with increasing prevalence from the first to the second sampling (50 % and 95 %, respectively). The last 20 larvae were from two tanks in which the larvae showed normal behaviour (n = 6 and n = 14) and were negative for the aquareovirus by real-time RT-PCR.

The tissue samples (liver, kidney) collected from different generations (2007–2013) of halibut at four different production sites in western Norway showed the presence of AHRV only in the 2013 generation at two production sites, with the exception of one positive in the 2010 generation at one of these sites. The positive fish from the 2013 generation had Ct values (AHRV-7) ranging from 20.0 to 32.0, while the housekeeping gene had Ct values around 16.0. Bacteria or parasites were not found in any of the tissues from these generations. However, the 2007-2012 generations from one site were positive for the presence of a microsporidian, possibly the one previously observed by Nilsen et al. [20].

Histopathology

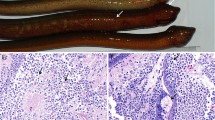

Sections of the moribund larvae showed multifocal necrosis in the liver and pancreas and areas of syncytial formation in these tissues (Fig. 1). Large subcellular inclusions were present in the syncytial areas (Fig. 1). There were no signs of inflammation in these areas. Food material could be observed in the gut of some individuals.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) showed that the subcellular inclusion in the syncytial areas in the liver and pancreas were viroplasm containing large amounts of viruses (Fig. 2A). The viroplasm, which was not surrounded by a membrane, consisted of amorphous material that constituted areas with variable electron density and virus-like particles (Fig. 2B). Tubular structures were also observed in the viroplasm, and at high magnification, the more electron-lucent areas of the viroplasm contained short, fibre-like structures (Fig. 3). The most frequently observed particles were spherical, about 70 nm in diameter, lacked an envelope, and had what seemed to be a double capsid structure (Fig. 4A). The inner capsid was about 34 nm in diameter. Smaller particles, about the same size as the inner capsid, were also observed in the viroplasm. These virus-like particles had a reovirus-like morphology.

A and B. Tubular structures (arrow) in the viroplasm. Virions (V). A. Bar = 200 nm. B. Viroplasm with tubular inclusions (arrow). Bar = 200 nm. C. Magnification of the central area of the viroplasm containing granular material (G), fibre-like material (F), and small electron-dense areas (ED). Bar = 200 nm

The necrotic areas in liver and pancreas tissues lacked cellular structure and consisted of cellular debris and virions (Fig. 4B).

Cell cultures

There was a progressive development of cytopathic effect (CPE) in both BF-2 cells and CHSE-214 cells. Microscopic examinations of the infected cell cultures showed multiple discrete plaques containing a central syncytium surrounded by slightly elongated cells at the margins of the syncytia (Fig. 5). The syncytium consisted of large, multinucleated cells, appeared after 6 days at 15 °C in BF-2 cells, and continued to grow until most of the monolayer was affected. The loss of these syncytial cells by lysis and the loss of the monolayer occurred after 11-13 days. This plaque formation progressed until most of the monolayer became affected. Subsequent passage of the supernatant from the infected cells did not result in CPE in BF-2 or CHSE-214 cells unless the supernatant was first subjected to freeze/thaw cycles (−80 °C and 20 °C). Testing of the supernatant and the remaining cells layer of the infected BF-2 cells before each passage resulted in Ct values as low as 12 using the real-time RT-PCR assay (AHRV-7 assay).

The development of CPE in CHSE-214 cells was similar to that observed in BF-2 cells, but at a slower rate, and the first syncytia were observed after 10 days (Fig. 5). The progression of CPE did not lead to a complete loss of the monolayer, but after 16 days, the loss of the syncytial cells started. Testing of the supernatant and the remaining cell layer in the infected CHSE-214 cells before each passage resulted in Ct values slightly above 20 (AHRV-7 assay).

No CPE was observed in ASK cells and RTgill cells, and the Ct values obtained using the AHRV-7 assay were always above 25 (range 25–30). The negative controls in all virus isolation procedures showed no CPE, and testing of cells from negative controls by real-time RT-PCR using the AHRV-7 assay gave negative results (data not shown).

Partial genome sequence of AHRV

Using primers targeting the RdRp gene from aquareoviruses (accession nos. AF418295, EF434978, and HM989931), the nearly complete sequence (3624 and 3246 nucleotides) from a segment containing one large open reading frame (ORF) were obtained from the two aquareovirus isolates, AHRV241013 and AHRV060513 (accession nos. KJ499467 and KJ499468). This segment codes for a protein with an RdRp catalytic domain between amino acids 551 and 799 predicted using Motif Scan (http://myhits.isb-sib.ch/cgi-bin/motif_scan). The conserved polymerase amino acid motifs DXXXXD (motif A), SG (motif B) and GDD (motif C), present in all members of the genera Aquareovirus and Orthoreovirus, were identified at positions 592–597, 649–650 and 740–742, respectively (accession no. KJ499467). Alignment of the nucleotide and the predicted amino acid sequences of AHRV with RdRp gene sequences from other aquareoviruses showed the highest similarity to chum salmon reovirus (CSRV-CS) and Atlantic salmon reovirus (ASRV-TS), respectively. Both isolates belong to the species Aquareovirus A (Table 3). The amino acid sequence identity between the putative RdRp from AHRV and turbot reovirus (SMReV) was 76.7 %, while the amino acid similarities to other aquareoviruses sequenced were below 60 %.

A partial sequence was also obtained from a segment that might code for a fusion-associated small transmembrane (FAST) protein (accession no. KJ913664). This sequence showed the highest nucleotide and predicted amino acid sequence similarity (52.6 % and 46.8 %) to Green River Chinook virus (accession no. KC588381), which is an unassigned member of the genus Aquareovirus, while the amino acid sequence identity compared to members of the species Aquareovirus A is <33.0 % (Table 4). The real-time RT-PCR assay (AHRV-7) used in this study targets this gene sequence from the two AHRV isolates.

Phylogeny

A phylogenetic tree showing the relationship of AHRV to other members of the genus Aquareovirus was constructed based on the available RdRp sequences (Fig. 6). AHRV clusters close to a clade containing CSRV, ASRV-AS and the turbot virus SMReV. American grass carp reovirus (AGCRV; species Aquareovirus G), is the second closest relative, while the other known Norwegian fish reovirus, piscine reovirus (PRV), is only distantly related to AHRV.

The phylogenetic position of the AHR virus based on analysis of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from selected members of the genera Aquareovirus and Orthoreovirus. Four orthoreoviruses (baboon orthoreovirus, BoRV; Broome virus, BroV; mammalian orthoreovirus 1; and mammalian orthoreovirus 2) were used as outgroups. The support values are frequencies (%) at which a given branch appeared in 1000 bootstrap replications

Discussion

An aquareovirus was isolated from Atlantic halibut larvae from a facility with a high mortality rate during the start-feeding phase (Table 3). This is the second member of the genus Aquareovirus isolated from strictly marine fish [21]. The larvae did not show any clinical signs of infection with parasites or bacteria. The observed mortality rate and results of histopathology and TEM studies showed changes similar to those described in moribund Atlantic halibut larvae in Canada and Scotland [6, 7]. The viroplasm and the morphology of the virions in the syncytial areas are also similar to those described in the two published studies. However, we did not find any changes in renal tissues as described by Cusak et al. [6] or syncytial giant cell formation of the mucosal epithelium of the intestine [7], but we did find severe lesions, with syncytial formation and necrosis, in the liver and pancreatic tissues. Mild pancreatitis, with influx of neutrophils and macrophages, was seen in some of the specimens from Scotland [7], while such inflammatory responses were not seen in the pancreatic tissues of the larvae in the present study. Despite some slight differences the histopathology, the disease appears to be same as that described in the two earlier studies, and the reovirus-like virions match the description given in the two papers [6, 7].

Species demarcation criteria for the genus Aquareovirus have traditionally been based on number of genome segments, host range and disease symptoms, number of capsid layers, presence of spiked or unspiked cores, cross-hybridization, electropherotype analysis by gel electrophoresis, serological comparison, ability to reassort during mixed infections, conserved terminal sequences, and RNA and amino acid sequence analysis [10]. However, members of a species in the genus Aquareovirus may also be identified based on the identity of RdRp sequences. Members of the same species should have >95 % amino acid (aa) sequence identity, while the corresponding values between species are 57–74 % [10]. Based on amino acid sequence identity of the two AHRV isolates, with the highest identity (80 %) to a member of the species Aquareovirus A (ASRV-TS), this virus is put in an uncertain position, with less than 95 % aa identity but higher than 74 % aa identity.

The host range of members assigned to the species Aquareovirus A includes American oyster and anadromous or fresh water fish only, while the host for AHRV is a strictly marine fish, the Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus) [22–25]. The closest aquareovirus marine relative of AHRV, based on the identity of the RdRp gene (SMReV, 76.7 %), has been isolated from turbot (Scophthalmus maximus) in China [21]. Turbot is a warm (temperate)-water species, while halibut is a cold-water species with little sharing of habitats with turbots. Hence, the host species, halibut, suggests that AHRV could be a member of a new distinct species within the genus Aquareovirus. However, more data are needed before a clear conclusion about the taxonomical status of the AHRV can be reached. A major problem for a proper assessment of the relationship of AHRV with respect to all aquareoviruses is the absence of genetic data from members of several species and unassigned reoviruses that could be members of the genus Aquareovirus.

The cytopathic effect (CPE) in the two cell cultures, BF-2 cells and CHSE-214 cells, showed discrete plaques containing large syncytia and elongated cells around the plaque margins. This CPE is characteristic for many Aquareovirus but does also occur with many orthoreoviruses [26, 27]. The fusion-associated small transmembrane (FAST) proteins are responsible for the induction of syncytia and may also trigger apoptosis [28–30]. The ability of the AHRV to cause syncytia in cell cultures suggests that this virus also carries a FAST protein. This is also supported by the partial sequences obtained from the AHRV isolates, showing 46.8 % nucleotide sequence identity to the FAST protein genes from the unassigned aquareovirus Green River Chinook virus. The identity compared to the recognized member of the species Aquareovirus A (CSRV) was <33.0 %.

AHRV is the second member of the family Reoviridae detected in farmed fish in Norway, the first being the unassigned virus, piscine reovirus (PRV), associated with heart and skeletal muscle inflammation in Atlantic salmon [31]. PRV is widespread in both farmed and wild Atlantic salmon in Norway [32], while AHRV has only been detected in farmed halibut fry. Future studies will show if this virus is also associated with the halibut fry mortalities in Canada and Scotland, and if AHRV is present in wild halibut in Norway.

References

Aspehaug V, Devold M, Nylund A (1999) The phylogenetic relationship of nervous necrosis virus from halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus). Bull Eur Assoc Fish Pathol 19:196–202

Biering E et al (1994) Susceptibility of Atlantic halibut Hippoglossus hippoglossus to infectious pancreatic necrosis virus. Dis Aquat Organ 20:183–190

Grotmol S et al (2000) Characterisation of the capsid protein gene from a nodavirus strain affecting the Atlantic halibut Hippoglossus hippoglossus and design of an optimal reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) detection assay. Dis Aquat Org 39:79–88

Johansen R (2013) Fiskehelserapporten 2012. Veterinærinstituttet, Oslo (ISSN 1893-1480)

Nylund A et al (2008) New clade of betanodaviruses detected in wild and farmed cod (Gadus morhua) in Norway. Arch Virol 153(3):541–547

Cusack RR et al (2001) Pathology associated with an aquareovirus in captive juvenile Atlantic halibut Hippoglossus hippoglossus and an experimental treatment strategy for a concurrent bacterial infection. Dis Aquat Organ 44(1):7–16

Ferguson HW, Millar SD, Kibenge FS (2003) Reovirus-like hepatitis in farmed halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus). Vet Rec 153(3):86–87

Lupiani B, Subramanian K, Samal SK (1995) Aquareoviruses. Annu Rev Fish Dis 5:175–208

Nibert ML, Duncan R (2013) Bioinformatics of recent aqua- and orthoreovirus isolates from fish: evolutionary gain or loss of FAST and fiber proteins and taxonomic implications. PLoS One 8(7):e68607

King AM et al (2012) Virus taxonomy: classification and nomenclature of viruses. Ninth report of the international committee on taxonomy of viruses, vol 9. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Andersen L, Hodneland K, Nylund A (2010) No influence of oxygen levels on pathogenesis and virus shedding in Salmonid alphavirus (SAV)-challenged Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.). Virol J 7:198

Devold M et al (2000) Use of RT-PCR for diagnosis of infectious salmon anaemia virus (ISAV) in carrier sea trout Salmo trutta after experimental infection. Dis Aquat Organ 40(1):9–18

Bols NC et al (1994) Development of a cell line from primary cultures of rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum), gills. J Fish Dis 17(6):601–611

Lannan CN, Winton JR, Fryer JL (1984) Fish cell lines: establishment and characterization of nine cell lines from salmonids. Vitro 20(9):671–676

Fryer JL, Lannan CN (1994) Three decades of fish cell culture: a current listing of cell lines derived from fishes. J Tissue Cult Methods 16(2):87–94

Korsnes K et al (2005) Viral encephalopathy and retinopathy (VER) in Atlantic salmon Salmo salar after intraperitoneal challenge with a nodavirus from Atlantic halibut Hippoglossus hippoglossus. Dis Aquat Org 68:7–15

Watanabe K et al (2006) Virus-like particles associated with heart and skeletal muscle inflammation (HSMI). Dis Aquat Organ 70(3):183–192

Overgard AC, Nerland AH, Patel S (2010) Evaluation of potential reference genes for real time RT-PCR studies in Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus Hippoglossus L.); during development, in tissues of healthy and NNV-injected fish, and in anterior kidney leucocytes. BMC Mol Biol 11:36

Page RD (1996) TreeView: an application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Comput Appl Biosci 12(4):357–358

Nilsen F, Ness A, Nylund A (1995) Observations on an intranuclear microsporidian in lymphoblasts from farmed Atlantic halibut larvae (Hippoglossus hippoglossus L.). J Eukaryot Microbiol 42(2):131–135

Ke F et al (2011) Turbot reovirus (SMReV) genome encoding a FAST protein with a non-AUG start site. BMC Genomics 12:323

Meyers TR (1979) A reo-like virus isolated from juvenile American oysters (Crassostrea virginica). J Gen Virol 43(1):203–212

Winton JR et al (1987) Morphological and biochemical properties of four members of a novel group of reoviruses isolated from aquatic animals. J Gen Virol 68(Pt 2):353–364

Samal SK et al (1990) Molecular characterization of a rotaviruslike virus isolated from striped bass (Morone saxatilis). J Virol 64(11):5235–5240

Attoui H et al (2002) Common evolutionary origin of aquareoviruses and orthoreoviruses revealed by genome characterization of Golden shiner reovirus, Grass carp reovirus, Striped bass reovirus and golden ide reovirus (genus Aquareovirus, family Reoviridae). J Gen Virol 83(Pt 8):1941–1951

Duncan R (1999) Extensive sequence divergence and phylogenetic relationships between the fusogenic and nonfusogenic orthoreoviruses: a species proposal. Virology 260(2):316–328

DeWitte-Orr SJ, Bols NC (2007) Cytopathic effects of chum salmon reovirus to salmonid epithelial, fibroblast and macrophage cell lines. Virus Res 126(1–2):159–171

Shmulevitz M, Duncan R (2000) A new class of fusion-associated small transmembrane (FAST) proteins encoded by the non-enveloped fusogenic reoviruses. EMBO J 19(5):902–912

Salsman J et al (2005) Extensive syncytium formation mediated by the reovirus FAST proteins triggers apoptosis-induced membrane instability. J Virol 79(13):8090–8100

Clarke P et al (2005) Mechanisms of apoptosis during reovirus infection. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 289:1–24

Palacios GF et al (2010) Heart and skeletal muscle inflammation of farmed salmon is associated with infection with a novel reovirus. PLoS one 5(7):e11487

Garseth AH et al (2013) Piscine reovirus (PRV) in wild Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar L., and sea-trout, Salmo trutta L., in Norway. J Fish Dis 36(5):483–493

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Blindheim, S., Nylund, A., Watanabe, K. et al. A new aquareovirus causing high mortality in farmed Atlantic halibut fry in Norway. Arch Virol 160, 91–102 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-014-2235-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-014-2235-8