Abstract

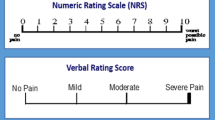

Understanding changes in patient-reported outcomes is indispensable for interpretation of results from clinical studies. As a consequence the term “minimal clinically important difference” (MCID) was coined in the late 1980s to ease classification of patients into improved, not changed or deteriorated. Several methodological categories have been developed determining the MCID, however, all are subject to weaknesses or biases reducing the validity of the reported MCID. The objective of this study was to determine the reproducibility and validity of a novel method for estimating low back pain (LBP) patients’ view of an acceptable change (MCIDpre) before treatment begins. One-hundred and forty-seven patients with chronic LBP were recruited from an out-patient hospital back pain unit and followed over an 8-week period. Original and modified versions of the Oswestry disability index (ODI), Bournemouth questionnaire (BQ) and numeric pain rating scale (NRSpain) were filled in at baseline. The modified questionnaires determined what the patient considered an acceptable post-treatment outcome which allowed us to calculate the MCIDpre. Concurrent comparisons between the MCIDpre, instrument measurement error and a retrospective approach of establishing the minimal clinically important difference (MCIDpost) were made. The results showed the prospective acceptable outcome method scores to have acceptable reproducibility outside measurement error. MCIDpre was 4.5 larger for the ODI and 1.5 times larger for BQ and NRSpain compared to the MCIDpost. Furthermore, MCIDpre and patients post-treatment acceptable change was almost equal for the NRSpain but not for the ODI and BQ. In conclusion, chronic LBP patients have a reasonably realistic idea of an acceptable change in pain, but probably an overly optimistic view of changes in functional and psychological/affective domains before treatment begins.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Aseltine RH, Carlson KJ, Fowler FJ Jr, Barry MJ (1995) Comparing prospective and retrospective measures of treatment outcomes. Med Care 33:AS67–AS76

Beaton DE (2000) Understanding the relevance of measured change through studies of responsiveness. Spine 25:3192–3199. doi:10.1097/00007632-200012150-00015

Bland JM, Altman DG (1986) Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1:307–310

Bland JM, Altman DG (1997) Cronbach’s alpha. BMJ 314:572

Bland JM, Altman DG (2003) Applying the right statistics: analyses of measurement studies. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 22:85–93. doi:10.1002/uog.122

Bolton JE, Breen AC (1999) The Bournemouth questionnaire: a short-form comprehensive outcome measure. I. Psychometric properties in back pain patients. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 22:503–510. doi:10.1016/S0161-4754(99)70001-1

Bolton JE, Humphreys BK (2002) The Bournemouth questionnaire: a short-form comprehensive outcome measure. II. Psychometric properties in neck pain patients. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 25:141–148. doi:10.1067/mmt.2002.123333

Childs JD, Piva SR, Fritz JM (2005) Responsiveness of the numeric pain rating scale in patients with low back pain. Spine 30:1331–1334. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000164099.92112.29

Copay AG, Subach BR, Glassman SD, Polly DW Jr, Schuler TC (2007) Understanding the minimum clinically important difference: a review of concepts and methods. Spine J 7:541–546. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2007.01.008

Crosby RD, Kolotkin RL, Williams GR (2003) Defining clinically meaningful change in health-related quality of life. J Clin Epidemiol 56:395–407. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00044-1

Davidson M, Keating JL (2002) A comparison of five low back disability questionnaires: reliability and responsiveness. Phys Ther 82:8–24

de Vet HC, Terwee CB, Knol DL, Bouter LM (2006) When to use agreement versus reliability measures. J Clin Epidemiol 59:1033–1039. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.10.015

de Vet HC, Terwee CB, Ostelo RW, Beckerman H, Knol DL, Bouter LM (2006) Minimal changes in health status questionnaires: distinction between minimally detectable change and minimally important change. Health Qual Life Outcomes 4:54–62. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-4-54

Farrar JT, Portenoy RK, Berlin JA, Kinman JL, Strom BL (2000) Defining the clinically important difference in pain outcome measures. Pain 88:287–294. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00339-0

Fayers PM, Machin D (2000) Mulit-item scales. In: Fayers PM, Machin D (eds) Quality of life: assessment, analysis and interpretation. Wiley, pp 72–90

Fischer D, Stewart AL, Bloch DA, Lorig K, Laurent D, Holman H (1999) Capturing the patient’s view of change as a clinical outcome measure. JAMA 282:1157–1162. doi:10.1001/jama.282.12.1157

Guyatt GH, Berman LB, Townsend M, Taylor DW (1985) Should study subjects see their previous responses? J Chronic Dis 38:1003–1007. doi:10.1016/0021-9681(85)90098-0

Guyatt GH, Norman GR, Juniper EF, Griffith LE (2002) A critical look at transition ratings. J Clin Epidemiol 55:900–908. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(02)00435-3

Guyatt GH, Osoba D, Wu AW, Wyrwich KW, Norman GR (2002) Methods to explain the clinical significance of health status measures. Mayo Clin Proc 77:371–383. doi:10.4065/77.4.371

Guyatt GH, Townsend M, Keller JL, Singer J (1989) Should study subjects see their previous responses: data from a randomized control trial. J Clin Epidemiol 42:913–920. doi:10.1016/0895-4356(89)90105-4

Hartvigsen J, Lauridsen HH, Ekstrom S, Nielsen MB, Lange F, Kofoed N et al (2005) Translation and validation of the danish version of the Bournemouth questionnaire. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 28:402–407. doi:10.1016/j.jmpt.2005.06.012

Jaeschke R, Singer J, Guyatt GH (1989) Measurement of health status. Ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Control Clin Trials 10:407–415. doi:10.1016/0197-2456(89)90005-6

Kalauokalani D, Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Koepsell TD, Deyo RA (2001) Lessons from a trial of acupuncture and massage for low back pain: patient expectations and treatment effects. Spine 26:1418–1424. doi:10.1097/00007632-200107010-00005

Lauridsen HH, Hartvigsen J, Manniche C, Korsholm L, Grunnet-Nilsson N (2006) Danish version of the Oswestry disability index for patients with low back pain. Part 1: Cross-cultural adaptation, reliability and validity in two different populations. Eur Spine J 15:1705–1716. doi:10.1007/s00586-006-0117-9

Lauridsen HH, Hartvigsen J, Manniche C, Korsholm L, Grunnet-Nilsson N (2006) Danish version of the Oswestry disability index for patients with low back pain. Part 2: Sensitivity, specificity and clinically significant improvement in two low back pain populations. Eur Spine J 15:1717–1728. doi:10.1007/s00586-006-0128-6

Lydick E, Epstein RS (1993) Interpretation of quality of life changes. Qual Life Res 2:221–226. doi:10.1007/BF00435226

Manniche C, Ankjær-Jensen A, Olesen A, Fog A, Williams K, Biering-Sørensen F (1999) Statens Institut for Medicinsk Teknologivurdering: Ondt i ryggen. Forekomst, behandling og forebyggelse i et MTV-perspektiv. Medicinsk Teknologivurdering Ser B 1(1)

Mcgraw KO, Wong SP (1996) Forming inferences about some intraclass correlation coefficients. Psychol Methods 1:30–46. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.1.1.30

McGregor AH, Hughes SP (2002) The evaluation of the surgical management of nerve root compression in patients with low back pain: Part 2: patient expectations and satisfaction. Spine 27:1471–1476. doi:10.1097/00007632-200207010-00019

Middel B, Goudriaan H, de Greef M, Stewart R, van Sonderen E, Bouma J et al (2006) Recall bias did not affect perceived magnitude of change in health-related functional status. J Clin Epidemiol 59:503–511. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.08.018

Norman GR, Stratford P, Regehr G (1997) Methodological problems in the retrospective computation of responsiveness to change: the lesson of Cronbach. J Clin Epidemiol 50:869–879. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(97)00097-8

Oort FJ, Visser MR, Sprangers MA (2005) An application of structural equation modeling to detect response shifts and true change in quality of life data from cancer patients undergoing invasive surgery. Qual Life Res 14:599–609. doi:10.1007/s11136-004-0831-x

Pellise F, Vidal X, Hernandez A, Cedraschi C, Bago J, Villanueva C (2005) Reliability of retrospective clinical data to evaluate the effectiveness of lumbar fusion in chronic low back pain. Spine 30:365–368. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000152096.48237.7c

Redelmeier DA, Guyatt GH, Goldstein RS (1996) Assessing the minimal important difference in symptoms: a comparison of two techniques. J Clin Epidemiol 49:1215–1219. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(96)00206-5

Revicki D, Hays RD, Cella D, Sloan J (2008) Recommended methods for determining responsiveness and minimally important differences for patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol 61:102–109. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.03.012

Rogosa DR, Willett JB (1983) Demonstrating the reliability of the difference score in the measurement of change. J Educ Meas 20:335–343. doi:10.1111/j.1745-3984.1983.tb00211.x

Roland M, Fairbank J (2000) The Roland-Morris disability questionnaire and the Oswestry disability questionnaire. Spine 25:3115–3124. doi:10.1097/00007632-200012150-00006

Sprangers MA, Van Dam FS, Broersen J, Lodder L, Wever L, Visser MR et al (1999) Revealing response shift in longitudinal research on fatigue–the use of the thentest approach. Acta Oncol 38:709–718. doi:10.1080/028418699432860

Streiner DL, Norman GR (2003) Health measurement scales. A practical guide to their development and use. Oxford Medical Publications, Oxford

Westaway MD, Stratford PW, Binkley JM (1998) The patient-specific functional scale: validation of its use in persons with neck dysfunction. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 27:331–338

Williamson A, Hoggart B (2005) Pain: a review of three commonly used pain rating scales. J Clin Nurs 14:798–804. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01121.x

Wright JG (1996) The minimal important difference: who’s to say what is important? J Clin Epidemiol 49:1221–1222. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(96)00207-7

Yelland MJ, Schluter PJ (2006) Defining worthwhile and desired responses to treatment of chronic low back pain. Pain Med 7:38–45. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00087.x

Acknowledgments

We thank Jytte Johannesen and Ida Bhanderi for administering the questionnaires. Furthermore, we would like to thank the management and staff at Backcenter Funen for their enthusiastic participation in the project. A special thanks to the seven chiropractic clinics for their involvement in recruiting patients for the study. The study was supported by the Foundation of Chiropractic Research and Postgraduate Education, The Faculty of Health Science at the University of Southern Denmark and The European Chiropractic Union.

Conflict of interest statement

The funding bodies have no control over design, conduct, data, analysis, review, reporting, or interpretation of the research conducted with the funds.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lauridsen, H.H., Manniche, C., Korsholm, L. et al. What is an acceptable outcome of treatment before it begins? Methodological considerations and implications for patients with chronic low back pain. Eur Spine J 18, 1858–1866 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-009-1070-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-009-1070-1