Abstract

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) exhibits a narrow host range and a specific tissue tropism. Mice expressing major entry receptors for HCV permit viral entry, and therefore the species tropism of HCV infection is considered to be reliant on the expression of the entry receptors. However, HCV receptor candidates are expressed and replication of HCV-RNA can be detected in several nonhepatic cell lines, suggesting that nonhepatic cells are also susceptible to HCV infection. Recently it was shown that the exogenous expression of a liver-specific microRNA, miR-122, facilitated the efficient replication of HCV not only in hepatic cell lines, including Hep3B and HepG2 cells, but also in nonhepatic cell lines, including Hec1B and HEK-293T cells, suggesting that miR-122 is required for the efficient replication of HCV in cultured cells. However, no infectious particle was detected in the nonhepatic cell lines, in spite of the efficient replication of HCV-RNA. In the nonhepatic cells, only small numbers of lipid droplets and low levels of very-low-density lipoprotein-associated proteins were observed compared with findings in the hepatic cell lines, suggesting that functional lipid metabolism participates in the assembly of HCV. Taken together, these findings indicate that miR-122 and functional lipid metabolism are involved in the tissue tropism of HCV infection. In this review, we would like to focus on the role of miR-122 and lipid metabolism in the cell tropism of HCV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

More than 170 million individuals worldwide are chronically infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV), and the cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) induced by HCV infection are life-threatening diseases [1]. On the other hand, HCV infection sometimes induces extra-hepatic manifestations (EHM), including mixed cryoglobulinemia and non-Hodgkin lymphoma [2–5]. The mechanisms of the pathogenesis and cell tropism of HCV have not been fully elucidated yet owing to the lack of an appropriate infection model. Although chimpanzees are susceptible to HCV infection, the use of these animals to study experimental infection is ethically problematic, and no other animal model with susceptibility to HCV infection has been established [6]. Furthermore, robust in vitro HCV propagation has been limited to the combination of cell-culture-adapted clones based on the genotype 2a JFH1 strain (HCVcc) and human liver cancer-derived Huh7 cells [7, 8]. The expression of a liver-specific microRNA, miR-122, has been shown to dramatically enhance the translation and replication of HCV-RNA [9]. Recently, several reports have shown that the exogenous expression of miR-122 facilitates the efficient replication of viral RNA in several hepatic and nonhepatic cell lines [10–13]. Of note, the clinical application of a specific inhibitor of miR-122 to chronic hepatitis C patients is now in progress [14]. In addition, it has been shown that liver-specific expression of very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL)-associated proteins is involved in the assembly of infectious HCV particles [15, 16]. This review will focus on the role of miR-122 expression and lipid metabolism in HCV infection.

microRNA and virus infection

miRNAs were first identified by Lee et al. [17] and since that time a great number of miRNAs have been registered in the miRNA database. miRNA incorporated into RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) interacts with a target mRNA via a specific recognition element. RISC contains argonaute 2 (Ago2), Dicer, and TAR RNA binding protein (TRBP) [18, 19]. In humans, Ago2 plays a pivotal role in the repression of translation of target genes [20]. It is now commonly believed that miRNAs play important roles in cell homeostasis, and that abnormality of miRNA expression participates in the development of several diseases, including viral infections [18, 19]. miRNAs encoded by Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) were identified in 2004 [4, 21], and over 200 viral miRNAs have been reported in several DNA viruses, especially in herpesviruses [22, 23]. Previous reports have shown that viral miRNAs participate in viral propagation by regulating the host gene expression [22, 23]. Many viral miRNAs suppress the host gene expression involved in innate and acquired immunities and enhance viral propagation [22, 24, 25]. Most RNA viruses replicate in the cytoplasm, and thus it had been believed that RNA viruses do not encode viral miRNAs. Rouha et al. [26] showed that an RNA virus, the tick-borne encephalitis virus, is capable of producing functional miRNA by the insertion of an miRNA element into viral RNA. Actually, it has been shown that virus-derived small RNAs emerge by infection with RNA viruses, including influenza virus and West Nile virus [27, 28]. These data suggest that both viral-encoded and host gene-derived miRNAs are involved in the regulation of viral propagation.

Liver-specific microRNA, miR-122

miR-122 is a liver-specific microRNA and is the microRNA most abundantly expressed in the liver [29–31]. Although Li et al. [32] have suggested that hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha (HNF4A) positively regulates the expression of miR-122, the details on the tissue specificity of miR-122 expression have not been fully elucidated yet. miR-122 targets the 3′untranslated region (3′UTR) of the mRNAs of cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding protein (CPEB), hemochromatosis (Hfe), hemojuverin (Hjv), disintegrin, and metalloprotease family 10 (ADAM10) and represses their translation [33–35]. miR-122 activates the translation of p53 mRNA through the suppression of CPEB and participates in cellular senescence [33]. Through the inhibition of Hfe and Hjv, miR-122 participates in iron metabolism [34]. Esau et al. [36] showed that miR-122 positively regulated lipid metabolism through the reduction of the mRNAs of lipid-associated proteins, and that inhibition of miR-122 expression attenuated liver steatosis in high-fat-fed mice, suggesting that miR-122 may be an attractive therapeutic target for metabolic diseases. miR-122 has also been shown to be involved in the propagation of hepatitis viruses, including hepatitis B virus (HBV) and HCV [9, 37, 38]. Wang et al. [38] have revealed that miR-122 suppresses cyclin G1, and this factor is known to enhance the replication of HBV by inhibiting the binding of p53 to HBV enhancer elements. In other reports, a low level of miR-122 expression in plasma was significantly associated with the incidence of HBV-related HCC [39]. These results suggest that miR-122 expression inhibits the propagation and pathogenesis of HBV. On the other hand, miR-122 expression enhances the propagation of HCV through genetic interaction with the 5′UTR of the HCV genome [9]. It is interesting to note that the effects of miR-122 expression on viral propagation are different between HBV and HCV.

miR-122 expression and HCV infection (Fig. 1)

Jopling et al. [9] reported for the first time that the inhibition of miR-122 dramatically decreased RNA replication in HCV replicon cells harboring subgenomic (SGR) or fullgenomic (FGR) viral RNA. They identified the 21 nucleotide (nt) of the miR-122 binding site in the 5′ end of the 5′UTR of HCV RNA. In addition, lack of enhancement of HCV replication by the expression of a mutant miR-122 incapable of binding to the 5′UTR was canceled by the introduction of a complementary mutation in the 5′UTR, suggesting that direct interaction of miR-122 with the 5′UTR is crucial for the enhancement of HCV replication. In subsequent reports, they identified a second adjacent miR-122 binding site in the 5′UTR [40]. Furthermore, ectopic expression of the mutant miR-122 rescued the replication of an HCV RNA possessing mutations in both miR-122 binding sites, suggesting that the interaction of miR-122 with both sites in the 5′UTR is required to augment viral replication. In addition, Machlin et al. [41] have revealed that not only the seed sequence but also nucleotides located at the positions of 15 and 16 in miR-122 are required for the enhancement of HCV replication. Interestingly, nucleotides 15 and 16 are not required for the conventional microRNA function of miR-122, suggesting that the conventional machinery of miR-122 is not involved in the miR-122-dependent enhancement of HCV replication. A recent study showed that the interaction of miR-122 with the 5′UTR of HCV was also required for the efficient production of infectious particles in cell culture [42].

miR-122 enhances the translation of hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA. Primary miRNA (pri-miRNA) transcribed by RNA polymerase II in the nucleus is processed into precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA) by Drosha and DiGeorge syndrome critical region protein 8 (DGCR8). Pre-miRNA is exported into the cytoplasm by nucleocytoplasmic shuttle protein exportin 5, processed to 22nt by dicer, and then incorporated into argonaute proteins to form the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). The passenger strand of miRNA (blue) is degraded and the guide strand (red) is matured in the RISC. Generally, miRNA represses the translation of host mRNA by binding to its 3’untranslated region (3′UTR). In contrast, liver-specific miR-122 binds to two sites in the 5′UTR of the HCV genome and enhances its translation and replication. GTP Guanosine-5-triphosphate, IRES internal ribosomal entry site

Although the precise mechanisms of the miR-122-mediated enhancement of HCV replication have not been fully elucidated yet, Henke et al. [43], by using polymerase defective viral RNA, showed that miR-122 stimulated the translation of HCV RNA by enhancing the association of ribosomes at an early initiation stage. They concluded that miR-122 might contribute to HCV liver tropism at the level of translation. Wilson et al. [44] showed that knockdown of Ago2 in SGR cells and HCVcc-infected cells attenuated HCV replication, and that knockdown of Ago2 also reduced the translation of the polymerase defective HCV RNA. Shimakami et al. [45] showed that miR-122 stabilized viral RNA and reduced its decay in concert with Ago2, and that miR-122-dependent stabilization of HCV RNA was not observed in Ago2-knockout murine embryonic fibroblasts. These results suggest that Ago2 is required for the efficient enhancement of both the translation and replication of HCV. On the other hand, Machlin et al. [41] have suggested that the 3′ overhang binding of miR-122 to the 5′ end of the HCV genome participates in circumvention from the recognition by the cytoplasmic RNA sensor, RIG-I. It is feasible to speculate that miR-122 has other functions in the HCV life cycle, in addition to the stabilization of viral RNA and evasion from the host’s innate immune response.

Establishment of new permissive cell lines for HCV propagation by the expression of miR-122

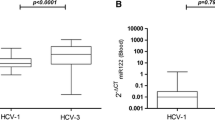

The lack of immunocompetent small animal models and cell culture systems to support the propagation of HCV in patient sera has hampered both the understanding of the HCV life cycle and the development of antiviral drugs [46]. HCV replicon cells in which the HCV genome autonomously replicates, and pseudotype viruses bearing HCV E1 and E2 glycoproteins were established to assess viral replication and entry, respectively [47, 48]. Afterwards, an infectious HCV derived from the JFH1 strain of genotype 2a (HCVcc) was developed [7, 8]. On the basis of the data obtained from these in vitro systems, the HCV life cycle has been clarified, and host factors involved in HCV propagation have been identified as therapeutic targets for chronic hepatitis C [46]. However, the robust propagation of HCVcc in well-characterized human liver cell lines other than Huh7 had not been successful until recently. Chang et al. [49] showed that the exogenous expression of miR-122 facilitated the replication of HCV RNA in kidney-derived HEK-293 cells. In addition, Lin et al. have demonstrated that the expression of miR-122 and depletion of interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF-3) permit replication of the HCV genome in mouse fibroblasts [50]. These results suggest that the expression of miR-122 might facilitate the efficient replication of HCVcc not only in hepatic cells but also in nonhepatic cells. In fact, the expression level of miR-122 in Huh7 cells has been shown to be higher than that in other hepatic cell lines, including Huh6, HepG2, and Hep3B cells [10]. Recently, two groups reported that miR-122 expression facilitated the efficient propagation of HCVcc in human hepatic cell lines [10, 11]. Narbus et al. [11] showed that HepG2 cells stably expressing CD81 and miR-122 supported efficient replication and the production of infectious particles. Interestingly, internal ribosomal entry site (IRES)-dependent translation of HCV exhibited a slight (1.4–2.1-fold) increase by the expression of miR-122 in HepG2 cells compared with that in parental cells, suggesting that miR-122 is required for efficient RNA replication but not in translation in HepG2 cells upon infection with HCVcc. Kambara et al. [10] established a novel permissive cell line for the propagation of HCVcc by the expression of miR-122 in Hep3B cells. miR-122 expression facilitated the efficient propagation of HCVcc and the establishment of HCV replicon cells in Hep3B cells. In addition, “cured” Hep3B cells established by the elimination of HCV RNA from the Hep3B replicon cells facilitated the efficient propagation of HCVcc compared to parental cells. Interestingly, the expression of miR-122 in the “cured” Hep3B cells was significantly higher than that in the parental cells. In addition, Ehrhadt et al. [51] have shown that the expression levels of miR-122 in Huh7-derived cured cells, including Huh7.5 and Huh-Lunet cells, are significantly higher than those in parental Huh7 cells. Collectively, these results suggest that miR-122 is a key determinant of the efficient replication of HCVcc in hepatic cell lines.

Expression of miR-122 facilitates the efficient replication of HCV in nonhepatic cells

In clinical studies, negative strands of HCV genome have been detected in nonhepatic tissues of chronic hepatitis C patients, suggesting the possibility of extrahepatic propagation of HCV [52–56]. In addition, HCV replication was detected in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of patients with occult HCV infection [57]. Roque-Afonso et al. [52] showed that highly divergent variants of HCV were detectable in PBMCs, but not in plasma or in liver, suggesting the possibility of the extrahepatic propagation of HCV. Furthermore, previous reports have suggested that recurrences of HCV infection after antiviral treatment or liver transplantation were attributable to chronic infection of HCV in extrahepatic tissues [58]. Collectively, these results might suggest a correlation between extrahepatic HCV replication and the development of EHM, including mixed cryoglobulinemia and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, which are frequently observed in chronic hepatitis C patients. However, details of the extrahepatic propagation of HCV have not been studied owing to the lack of an appropriate experimental model [59, 60].

HCV replicon cells have been established in several nonhepatic cell lines. Kato et al. [61] established JFH1-based SGR cells by using HeLa and HEK293 cells, suggesting that the HCV genome can replicate in nonhepatic cells. In addition, Fletcher et al. [62] showed that brain endothelial cells supported HCV entry and replication, suggesting that HCV infection in the central nervous system participates in HCV-associated neuropathologies. Given the marked effects of miR-122 expression on the propagation of HCVcc in hepatic cell lines, we hypothesized that the expression of miR-122 in nonhepatic cell lines would facilitate the establishment of novel permissive cell lines for HCV. Recently, we have shown that Hec1B cells derived from the human uterus exhibited a low level of viral replication and the exogenous expression of miR-122 significantly enhanced replication upon infection with HCVcc [63]. In addition, an miR-122-specific inhibitor for miR-122 called locked nucleic acid (LNA-miR-122) inhibited the enhancement of HCVcc replication in Hec1B cells expressing miR-122, while the basal replication of HCVcc in parental Hec1B cells was resistant to the treatment. These results suggest that Hec1B cells permit HCV replication in an miR-122-independent manner and the exogenous expression of miR-122 enhances viral replication. In this report, cured Hec1B cells established by the elimination of HCV RNA from Hec1B replicon cells exhibited more potent replication of HCVcc than the parental cells. As seen in the cured Hep3B cells, the expression levels of miR-122 in the Hec1B cured cells were significantly higher than those in the parental cells [63]. Taken together, these results show that the expression of miR-122 facilitates the replication of HCVcc in nonhepatic cells.

Viral assembly in nonhepatic cells

Previous reports have shown that the production of VLDL is involved in the formation of infectious HCV particles [15, 16]. Apolipoprotein B (ApoB), apolipoprotein E (ApoE), and microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTTP) have major roles in the secretion of VLDL. Gastaminza et al. [15] have demonstrated that ApoB and MTTP are cellular factors essential for the efficient assembly of infectious HCV particles. They concluded that HCV acquired hepatocyte tropism through utilization of the VLDL secretory pathway. On the other hand, studies by other groups have demonstrated that infectious HCV particles are highly enriched in ApoE, which is a major determinant of HCV infectivity and production [64]. In their reports, small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated knockdown of ApoB and treatment with MTTP inhibitors exhibited no significant effect on the infectivity and production of HCV, suggesting that ApoE but not ApoB is required for viral assembly. In addition, Mancone et al. [65] have shown that apolipoprotein A-I (ApoA-I) is required for the replication of HCV and the production of infectious particles. Collectively, these results suggest that several VLDL-associated proteins are involved in HCV assembly.

In our recent report, the viral assembly process was shown to be impaired in nonhepatic cells exogenously expressing miR-122, in spite of the efficient replication of the HCV genome [63]. Interestingly, low but substantial infectious titers were detected in hepatic Hep3B cells upon infection with HCVcc, even though the RNA replication was lower than that in nonhepatic Hec1B cells expressing miR-122. The expression levels of VLDL-associated proteins, including ApoE, ApoB, and MTTP, in nonhepatic cell lines were significantly lower than those in hepatic cell lines, suggesting that lack of expression of VLDL-associated proteins is one of the reasons for the inability of nonhepatic cells to produce infectious particles. Miyanari et al. [66] showed that lipid droplets (LDs) were required for the formation of infectious particles via interaction between the core protein and viral RNA. Interestingly, only a small amount of LDs was detected in nonhepatic cells, including Hec1B and HEK293T cells, compared with the amount in hepatic cell lines, suggesting that a low level of LD formation is also involved in the impairment of infectious particle formation in nonhepatic cells [63]. Taken together, these findings suggest the possibility that the reconstitution of functional lipid metabolism in nonhepatic cells facilitates the production of infectious particles.

Tropism of HCV infection

In many cases, the cell tropism of viral infection is defined by the expression of virus-specific receptors. The expression of CD4 and chemokine receptors has an important role in the determination of the lymphotropism of human immunodeficiency virus infection [67]. In measles virus infection, the signaling lymphocyte activation molecule is a determinant of lymphotropism [68, 69]. Previous reports have shown that human CD81, scavenger receptor class B1 (SR-B1), Claudin1 (CLDN1), and Occludin (OCLN) are crucial for HCV entry [70–73]. Although murine cells cannot permit HCV entry, the exogenous expression of human-derived receptor candidates in murine cells has been shown to facilitate HCV entry, suggesting that HCV-specific receptors participate in the determination of the cell tropism of HCV [74, 75]. However, previous reports have also revealed that HCV receptor candidates were highly expressed in many nonhepatic tissues [62, 76], and our recent report has demonstrated that many nonhepatic cells permit the entry of HCV pseudotypes [63]. In addition, many reports have suggested the possibility of HCV replication in extrahepatic sites such as PBMCs and neuronal cells [55, 62], suggesting that host factors other than receptors could be involved in the tissue tropism of HCV.

Although previous reports have shown that host factors such as VAMP-associated protein (VAP)-A, VAP-B, cyclophilin A, FK506 binding protein 8, and heat shock protein 90 participate in HCV replication, these molecules are unlikely to participate in the determination of the liver tropism of HCV, owing to their ubiquitous expression [46, 77–79]. As described above, miR-122 is abundantly expressed specifically in hepatocytes and is essential for the efficient replication of HCV. In addition, a recent report showed that hepatocyte-like cells derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) expressed high levels of miR-122 and supported the entire life cycle of HCVcc, suggesting that miR-122 might be one of the most critical determinants of the liver tropism of HCV infection [80, 81]. On the other hand, VLDL-associated proteins, including ApoB, ApoE, and MTTP, are specifically expressed in hepatic cells, and no infectious particles are produced in nonhepatic cells such as Hec1B and 293T-CLDN cells [63]. Collectively, these data suggest that the VLDL-producing system is involved in the liver tropism of HCV.

Although HCV can internalize not only into hepatocytes but also into nonhepatic cells through receptor-mediated endocytosis, miR-122 expression and functional lipid metabolism in hepatocytes facilitate the efficient replication and assembly of HCV (Fig. 2). On the other hand, lack of expression of miR-122 and VLDL-associated proteins might be associated with the incomplete propagation of HCV in nonhepatic cells (Fig. 2).

HCV replication in hepatocytes and nonhepatic cells. Chronic HCV infection induces liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and is also often associated with the development of extrahepatic manifestations (EHM) such as malignant lymphoma and autoimmune diseases. Not only hepatocytes but also nonhepatic cells express major HCV receptors, including CD81, SR-BI, CLDN1, and OCLN. In hepatocytes, functional expression of miR-122 and lipid metabolism facilitate the efficient propagation of HCV. In contrast, the lack of expression of miR-122 and very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL)-associated proteins might be associated with the incomplete propagation of HCV in nonhepatic cells. Low levels of HCV replication in nonhepatic cells may participate in the development of EHM

Conclusion

Recent progress in HCV research has revealed that the tissue tropism of HCV is reliant on the expression of liver-specific miR-122 and a functional lipid metabolism rather than being reliant on the expression of entry receptors. However, the molecular mechanisms of the enhancement of viral replication induced by the interaction of miR-122 with the 5′UTR of HCV and the assembly of viral particles via VLDL-producing machinery remain unknown. In addition, the participation of nonhepatic cells in the development of EHM has been suggested, through an incomplete or low level of HCV replication. Elucidation of the liver tropism of HCV will provide a clue to the development of new antiviral drugs for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C and could lead to an understanding of the pathogenesis of EHM induced by HCV infection.

References

Seeff LB. Natural history of chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2002;36:S35–46.

Hartridge-Lambert SK, Stein EM, Markowitz AJ, Portlock CS. Hepatitis C and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the clinical perspective. Hepatology. 2012;55:634–41.

Calleja JL, Albillos A, Moreno-Otero R, Rossi I, Cacho G, Domper F, et al. Sustained response to interferon-alpha or to interferon-alpha plus ribavirin in hepatitis C virus-associated symptomatic mixed cryoglobulinaemia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:1179–86.

Gumber SC, Chopra S. Hepatitis C: a multifaceted disease. Review of extrahepatic manifestations. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:615–20.

Galossi A, Guarisco R, Bellis L, Puoti C. Extrahepatic manifestations of chronic HCV infection. J Gastrointest Liver Dis. 2007;16:65–73.

Bukh J. A critical role for the chimpanzee model in the study of hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2004;39:1469–75.

Wakita T, Pietschmann T, Kato T, Date T, Miyamoto M, Zhao Z, et al. Production of infectious hepatitis C virus in tissue culture from a cloned viral genome. Nat Med. 2005;11:791–6.

Lindenbach BD, Evans MJ, Syder AJ, Wolk B, Tellinghuisen TL, Liu CC, et al. Complete replication of hepatitis C virus in cell culture. Science. 2005;309:623–6.

Jopling CL, Yi M, Lancaster AM, Lemon SM, Sarnow P. Modulation of hepatitis C virus RNA abundance by a liver-specific microRNA. Science. 2005;309:1577–81.

Kambara H, Fukuhara T, Shiokawa M, Ono C, Ohara Y, Kamitani W, et al. Establishment of a novel permissive cell line for the propagation of hepatitis C virus by expression of microRNA miR122. J Virol. 2012;86:1382–93.

Narbus CM, Israelow B, Sourisseau M, Michta ML, Hopcraft SE, Zeiner GM, et al. HepG2 cells expressing microRNA miR-122 support the entire hepatitis C virus life cycle. J Virol. 2011;85:12087–92.

Sainz B Jr, Barretto N, Yu X, Corcoran P, Uprichard SL. Permissiveness of human hepatoma cell lines for HCV infection. Virol J. 2012;9:30.

Fukuhara T, Tani H, Shiokawa M, Goto Y, Abe T, Taketomi A, et al. Intracellular delivery of serum-derived hepatitis C virus. Microbes Infect. 2011;13:405–12.

Lanford RE, Hildebrandt-Eriksen ES, Petri A, Persson R, Lindow M, Munk ME, et al. Therapeutic silencing of microRNA-122 in primates with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Science. 2010;327:198–201.

Gastaminza P, Cheng G, Wieland S, Zhong J, Liao W, Chisari FV. Cellular determinants of hepatitis C virus assembly, maturation, degradation, and secretion. J Virol. 2008;82:2120–9.

Cun W, Jiang J, Luo G. The C-terminal alpha-helix domain of apolipoprotein E is required for interaction with nonstructural protein 5A and assembly of hepatitis C virus. J Virol. 2010;84:11532–41.

Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993;75:843–54.

Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–33.

Huntzinger E, Izaurralde E. Gene silencing by microRNAs: contributions of translational repression and mRNA decay. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:99–110.

Hutvagner G, Simard MJ. Argonaute proteins: key players in RNA silencing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:22–32.

Pfeffer S, Zavolan M, Grasser FA, Chien M, Russo JJ, Ju J, et al. Identification of virus-encoded microRNAs. Science. 2004;304:734–6.

Boss IW, Renne R. Viral miRNAs and immune evasion. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1809:708–14.

Ziegelbauer JM. Functions of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus microRNAs. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1809:623–30.

Umbach JL, Kramer MF, Jurak I, Karnowski HW, Coen DM, Cullen BR. MicroRNAs expressed by herpes simplex virus 1 during latent infection regulate viral mRNAs. Nature. 2008;454:780–3.

Nachmani D, Stern-Ginossar N, Sarid R, Mandelboim O. Diverse herpesvirus microRNAs target the stress-induced immune ligand MICB to escape recognition by natural killer cells. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:376–85.

Rouha H, Thurner C, Mandl CW. Functional microRNA generated from a cytoplasmic RNA virus. Nucl Acids Res. 2010;38:8328–37.

Perez JT, Varble A, Sachidanandam R, Zlatev I, Manoharan M, Garcia-Sastre A, et al. Influenza A virus-generated small RNAs regulate the switch from transcription to replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:11525–30.

Hussain M, Torres S, Schnettler E, Funk A, Grundhoff A, Pijlman GP, et al. West Nile virus encodes a microRNA-like small RNA in the 3′ untranslated region which up-regulates GATA4 mRNA and facilitates virus replication in mosquito cells. Nucl Acids Res. 2012;40:2210–23.

Lagos-Quintana M, Rauhut R, Yalcin A, Meyer J, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T. Identification of tissue-specific microRNAs from mouse. Curr Biol. 2002;12:735–9.

Chang J, Provost P, Taylor JM. Resistance of human hepatitis delta virus RNAs to dicer activity. J Virol. 2003;77:11910–7.

Chang J, Nicolas E, Marks D, Sander C, Lerro A, Buendia MA, et al. miR-122, a mammalian liver-specific microRNA, is processed from hcr mRNA and may downregulate the high affinity cationic amino acid transporter CAT-1. RNA Biol. 2004;1:106–13.

Li ZY, Xi Y, Zhu WN, Zeng C, Zhang ZQ, Guo ZC, et al. Positive regulation of hepatic miR-122 expression by HNF4alpha. J Hepatol. 2011;55:602–11.

Burns DM, D’Ambrogio A, Nottrott S, Richter JD. CPEB and two poly(A) polymerases control miR-122 stability and p53 mRNA translation. Nature. 2011;473:105–8.

Castoldi M, Vujic Spasic M, Altamura S, Elmen J, Lindow M, Kiss J, et al. The liver-specific microRNA miR-122 controls systemic iron homeostasis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:1386–96.

Bai S, Nasser MW, Wang B, Hsu SH, Datta J, Kutay H, et al. MicroRNA-122 inhibits tumorigenic properties of hepatocellular carcinoma cells and sensitizes these cells to sorafenib. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:32015–27.

Esau C, Davis S, Murray SF, Yu XX, Pandey SK, Pear M, et al. miR-122 regulation of lipid metabolism revealed by in vivo antisense targeting. Cell Metab. 2006;3:87–98.

Qiu L, Fan H, Jin W, Zhao B, Wang Y, Ju Y, et al. miR-122-induced down-regulation of HO-1 negatively affects miR-122-mediated suppression of HBV. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;398:771–7.

Wang S, Qiu L, Yan X, Jin W, Wang Y, Chen L, et al. Loss of microRNA 122 expression in patients with hepatitis B enhances hepatitis B virus replication through cyclin G(1)-modulated P53 activity. Hepatology. 2012;55:730–41.

Zhou J, Yu L, Gao X, Hu J, Wang J, Dai Z, et al. Plasma microRNA panel to diagnose hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4781–8.

Jopling CL, Schutz S, Sarnow P. Position-dependent function for a tandem microRNA miR-122-binding site located in the hepatitis C virus RNA genome. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:77–85.

Machlin ES, Sarnow P, Sagan SM. Masking the 5′ terminal nucleotides of the hepatitis C virus genome by an unconventional microRNA-target RNA complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:3193–8.

Shimakami T, Yamane D, Welsch C, Hensley L, Jangra RK, Lemon SM. Base pairing between hepatitis C virus RNA and microRNA 122 3′ of its seed sequence is essential for genome stabilization and production of infectious virus. J Virol. 2012;86:7372–83.

Henke JI, Goergen D, Zheng J, Song Y, Schuttler CG, Fehr C, et al. MicroRNA-122 stimulates translation of hepatitis C virus RNA. EMBO J. 2008;27:3300–10.

Wilson JA, Zhang C, Huys A, Richardson CD. Human Ago2 is required for efficient microRNA 122 regulation of hepatitis C virus RNA accumulation and translation. J Virol. 2011;85:2342–50.

Shimakami T, Yamane D, Jangra RK, Kempf BJ, Spaniel C, Barton DJ, et al. Stabilization of hepatitis C virus RNA by an Ago2-miR-122 complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:941–6.

Moriishi K, Matsuura Y. Host factors involved in the replication of hepatitis C virus. Rev Med Virol. 2007;17:343–54.

Lohmann V, Korner F, Koch J, Herian U, Theilmann L, Bartenschlager R. Replication of subgenomic hepatitis C virus RNAs in a hepatoma cell line. Science. 1999;285:110–3.

Bartosch B, Dubuisson J, Cosset FL. Infectious hepatitis C virus pseudo-particles containing functional E1–E2 envelope protein complexes. J Exp Med. 2003;197:633–42.

Chang J, Guo JT, Jiang D, Guo H, Taylor JM, Block TM. Liver-specific microRNA miR-122 enhances the replication of hepatitis C virus in nonhepatic cells. J Virol. 2008;82:8215–23.

Lin LT, Noyce RS, Pham TN, Wilson JA, Sisson GR, Michalak TI, et al. Replication of subgenomic hepatitis C virus replicons in mouse fibroblasts is facilitated by deletion of interferon regulatory factor 3 and expression of liver-specific microRNA 122. J Virol. 2010;84:9170–80.

Ehrhardt M, Leidinger P, Keller A, Baumert T, Diez J, Meese E, et al. Profound differences of microRNA expression patterns in hepatocytes and hepatoma cell lines commonly used in hepatitis C virus studies. Hepatology. 2011;54:1112–3

Roque-Afonso AM, Ducoulombier D, Di Liberto G, Kara R, Gigou M, Dussaix E, et al. Compartmentalization of hepatitis C virus genotypes between plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Virol. 2005;79:6349–57.

Zehender G, De Maddalena C, Bernini F, Ebranati E, Monti G, Pioltelli P, et al. Compartmentalization of hepatitis C virus quasispecies in blood mononuclear cells of patients with mixed cryoglobulinemic syndrome. J Virol. 2005;79:9145–56.

Blackard JT, Kemmer N, Sherman KE. Extrahepatic replication of HCV: insights into clinical manifestations and biological consequences. Hepatology. 2006;44:15–22.

Laskus T, Operskalski EA, Radkowski M, Wilkinson J, Mack WJ, deGiacomo M, et al. Negative-strand hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from anti-HCV-positive/HIV-infected women. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:124–33.

Fletcher NF, Wilson GK, Murray J, Hu K, Lewis A, Reynolds GM, et al. Hepatitis C virus infects the endothelial cells of the blood-brain barrier. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:634–43 e6.

Castillo I, Rodriguez-Inigo E, Bartolome J, de Lucas S, Ortiz-Movilla N, Lopez-Alcorocho JM, et al. Hepatitis C virus replicates in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with occult hepatitis C virus infection. Gut. 2005;54:682–5.

Laskus T, Radkowski M, Wilkinson J, Vargas H, Rakela J. The origin of hepatitis C virus reinfecting transplanted livers: serum-derived versus peripheral blood mononuclear cell-derived virus. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:417–21.

Ito M, Masumi A, Mochida K, Kukihara H, Moriishi K, Matsuura Y, et al. Peripheral B cells may serve as a reservoir for persistent hepatitis C virus infection. J Innate Immun. 2010;2:607–17.

Ramirez S, Perez-Del-Pulgar S, Carrion JA, Costa J, Gonzalez P, Massaguer A, et al. Hepatitis C virus compartmentalization and infection recurrence after liver transplantation. Am J Transpl. 2009;9:1591–601.

Kato T, Date T, Miyamoto M, Zhao Z, Mizokami M, Wakita T. Nonhepatic cell lines HeLa and 293 support efficient replication of the hepatitis C virus genotype 2a subgenomic replicon. J Virol. 2005;79:592–6.

Fletcher NF, Yang JP, Farquhar MJ, Hu K, Davis C, He Q, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection of neuroepithelioma cell lines. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1365–74.

Fukuhara T, Kambara H, Shiokawa M, Ono C, Katoh H, Morita E, et al. Expression of microRNA miR-122 facilitates an efficient replication in nonhepatic cells upon infection with hepatitis C virus. J Virol. 2012;86:7918–33.

Jiang J, Luo G. Apolipoprotein E but not B is required for the formation of infectious hepatitis C virus particles. J Virol. 2009;83:12680–91.

Mancone C, Steindler C, Santangelo L, Simonte G, Vlassi C, Longo MA, et al. Hepatitis C virus production requires apolipoprotein A-I and affects its association with nascent low-density lipoproteins. Gut. 2010;60:378–86.

Miyanari Y, Atsuzawa K, Usuda N, Watashi K, Hishiki T, Zayas M, et al. The lipid droplet is an important organelle for hepatitis C virus production. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1089–97.

Dragic T, Litwin V, Allaway GP, Martin SR, Huang Y, Nagashima KA, et al. HIV-1 entry into CD4+ cells is mediated by the chemokine receptor CC-CKR-5. Nature. 1996;381:667–73.

Tatsuo H, Ono N, Tanaka K, Yanagi Y. SLAM (CDw150) is a cellular receptor for measles virus. Nature. 2000;406:893–7.

Yanagi Y, Takeda M, Ohno S. Measles virus: cellular receptors, tropism and pathogenesis. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:2767–79.

Pileri P, Uematsu Y, Campagnoli S, Galli G, Falugi F, Petracca R, et al. Binding of hepatitis C virus to CD81. Science. 1998;282:938–41.

Scarselli E, Ansuini H, Cerino R, Roccasecca RM, Acali S, Filocamo G, et al. The human scavenger receptor class B type I is a novel candidate receptor for the hepatitis C virus. EMBO J. 2002;21:5017–25.

Evans MJ, von Hahn T, Tscherne DM, Syder AJ, Panis M, Wolk B, et al. Claudin-1 is a hepatitis C virus co-receptor required for a late step in entry. Nature. 2007;446:801–5.

Ploss A, Evans MJ, Gaysinskaya VA, Panis M, You H, de Jong YP, et al. Human occludin is a hepatitis C virus entry factor required for infection of mouse cells. Nature. 2009;457:882–6.

Michta ML, Hopcraft SE, Narbus CM, Kratovac Z, Israelow B, Sourisseau M, et al. Species-specific regions of occludin required by hepatitis C virus for cell entry. J Virol. 2010;84:11696–708.

Dorner M, Horwitz JA, Robbins JB, Barry WT, Feng Q, Mu K, et al. A genetically humanized mouse model for hepatitis C virus infection. Nature. 2011;474:208–11.

Tani H, Komoda Y, Matsuo E, Suzuki K, Hamamoto I, Yamashita T, et al. Replication-competent recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus encoding hepatitis C virus envelope proteins. J Virol. 2007;81:8601–12.

Hamamoto I, Nishimura Y, Okamoto T, Aizaki H, Liu M, Mori Y, et al. Human VAP-B is involved in hepatitis C virus replication through interaction with NS5A and NS5B. J Virol. 2005;79:13473–82.

Foster TL, Gallay P, Stonehouse NJ, Harris M. Cyclophilin A interacts with domain II of hepatitis C virus NS5A and stimulates RNA binding in an isomerase-dependent manner. J Virol. 2011;85:7460–4.

Okamoto T, Nishimura Y, Ichimura T, Suzuki K, Miyamura T, Suzuki T, et al. Hepatitis C virus RNA replication is regulated by FKBP8 and Hsp90. EMBO J. 2006;25:5015–25.

Schwartz RE, Trehan K, Andrus L, Sheahan TP, Ploss A, Duncan SA, et al. Modeling hepatitis C virus infection using human induced pluripotent stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:2544–8.

Wu X, Robotham JM, Lee E, Dalton S, Kneteman NM, Gilbert DM, et al. Productive hepatitis C virus infection of stem cell-derived hepatocytes reveals a critical transition to viral permissiveness during differentiation. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002617.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fukuhara, T., Matsuura, Y. Role of miR-122 and lipid metabolism in HCV infection. J Gastroenterol 48, 169–176 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-012-0661-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-012-0661-5