Abstract

Background and purpose

Cancer patients treated with targeted therapies (e.g., epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors) are susceptible to dermatologic adverse events (AEs) including secondary skin infections. Whereas infections such as paronychia and cellulitis have been reported, nasal vestibulitis (NV) has not been described with the use of these agents. The aim of our study was to characterize NV in cancer patients treated with targeted therapies.

Methods

We utilized a retrospective chart review of cancer patients who had been referred to dermatology and were diagnosed with NV. We recorded data including demographics, referral reason, underlying malignancy, targeted anticancer regimen, NV treatment, and nasal bacterial culture results.

Results

One Hundred Fifteen patients were included in the analysis, of which 13 % experienced multiple NV episodes. Skin rash was the most common reason (90 %) for a dermatology referral. The most common underlying malignancies were lung (43 %), breast (19 %), and colorectal (10 %) cancer. Sixty-eight percent of patients had been treated with an EGFRI-based regimen. Nasal cultures were obtained in 60 % of episodes, of which 94 % were positive for one or more organisms. Staphylococcus aureus was the most commonly isolated organism [methicillin-sensitive S. aureus 43 %; methicillin-resistant S. aureus 3 %].

Conclusions

We report the incidence and characteristics of an unreported, yet frequent dermatologic condition in cancer patients treated with targeted therapies. These findings provide the basis for additional studies to describe the incidence, treatment, and consequences of this event. A better understanding of NV would mitigate its impact on patients’ quality of life and risk for additional dermatologic AEs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Targeted therapies allow for a tailored approach to treating patients with various cancers, by targeting pathways critical to cancer cell growth and proliferation. Although marked by a favorable adverse event (AE) profile vis-à-vis conventional chemotherapy, the ensuing dermatologic AEs are prevalent and concerning [1, 2]. Examples include rash, xerosis, pruritus, mucositis, hand-foot skin reaction, paronychia, and hair and nail changes, all of which impair patients’ quality of life [2–4]. Notably, skin infections (bacterial, viral, dermatophytic) seem prevalent [5] but have received little attention. In our clinic, we have increasingly encountered nasal vestibulitis (NV) in patients treated with targeted therapies, though a literature search did not reveal any reported cases.

NV is an acute inflammation of the tissue around the nasal vestibule—a part of the anterior nasal cavity. The area is lined by keratinized stratified squamous epithelium and abundant hair follicles [6], and is an ecological niche of Staphylococcus aureus, with estimated carriage rates of 20 % in the general population [7]. Although no studies to date have investigated the incidence or prevalence of NV, it appears to be a common condition [8], especially in the elderly. Common microbial flora of the nose and paranasal sinuses includes S. aureus, S. epidermidis, Haemophilus influenzae, Corynebacteria, Micrococci, Streptococcus pneumonia and viridans, along with the anaerobic Propionibacterium acnes [9]. Upon epithelial barrier disruption, the colonizing organisms can become pathogenic [10]. For example, S. aureus nasal carriage is a risk factor for other skin and soft tissue infections, both community-acquired and nosocomial [11]. S. aureus carriage rates vary by age, gender, and ethnicity, with higher nasal colonization rates among healthcare workers, patients with dermatologic conditions (e.g., psoriasis, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma or T-cell lymphoma, mycosis fungoides, Sezary syndrome) or diabetes mellitus, and those receiving hemodialysis [11–15].

Clinically, patients with NV present with local erythema, nasal tenderness, crusting, and/or epistaxis. Use of topical emollients and antibiotics may suffice for mild episodes, although severe cases mandate systemic antibiotics. Predisposing factors for NV range from environmental (e.g., low humidity, altered pH), mechanical (e.g., constant rhinorrhea, nose picking, foreign bodies, nasal trauma/stents), and individual variables (e.g., smoking, immunosuppression), to medication use (e.g., diuretics, isotretinoin), surgery, infections (e.g., herpes simplex/zoster), and systemic conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus [16–21]. Notably, any condition leading to epithelial disruption can result in entry of microbes. Infections within the “danger area” of the face, which includes the nasal vestibule, portend an increased risk of spread to contiguous facial areas and to the cavernous sinuses through valveless facial veins [20, 22]. Building upon previous findings of Eilers et al. and Eames et al. [5, 23], which suggest an increased rate of skin and nail infections in patients receiving targeted agents, we characterize and report the occurrence of NV in cancer patients.

Materials and methods

We conducted an Institutional Review Board-approved retrospective chart review of electronic medical records (EMRs) of cancer patients treated in the Dermatology Service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC), and the Waterland Hospital in Purmerend, The Netherlands. The search was limited to patients, who in addition to their AEs, also had NV. At MSKCC, we utilized the Information Systems’ DataLine service to identify relevant EMRs (April 2010–July 2013), using “nasal vestibulitis” as the search term.

Data retrieved from the EMRs included patient demographics, age, gender, ethnicity, referral reason, referral season, underlying malignancy and treatment, pertinent medical history, nasal symptoms including concurrent rash or xerosis (with severity/grade, if noted), risk factors for nasal conditions, concomitant anticoagulant and/or inhalant use, current upper respiratory tract infection (URTI), current smoking status, and NV treatment and outcome.

When available, we retrieved wound culture and antimicrobial susceptibility results of samples obtained from the anterior nares during the episodes of NV. A swab collected from superficial nasal wounds was used to inoculate bacteria on colistin-nalidixic acid, MacConkey, and chocolate agar plates (BBL, Becton-Dickinson, Inc., Sparks, MD). The plates were incubated for 3 days at 35 °C and checked daily for evidence of growth. All recovered isolates were fully identified except for isolates resembling usual skin flora (including Corynebacteria, Coagulase-negative Staphylococci in mixed culture, group D streptococci (not enterococci), Lactobacillus sp., Micrococcus sp., and viridans streptococcal species). Identification and in vitro antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed using an automated platform (MicroScan Autoscan-4 system, Siemens Inc., Hoffman Estates, IL). Interpretation of susceptibility results was done in accordance with guidelines from the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [24].

The following data were extracted: pathogen, growth quantity, and antibiotic susceptibilities, including minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values. Data were recorded for any bacterial cultures (performed simultaneously) of skin lesions elsewhere, and their results were correlated with respect to bacterial identity, antibiotic susceptibility, and MIC profile. We also recorded modifications in NV treatment that were based on reports of susceptibility testing.

Results were entered into a database and descriptive statistics were employed. Goodness of fit chi-square analysis was performed using Stata/SE 12.0 to examine whether significant differences (P < 0.05) existed with NV seasonal distribution or reason for dermatology referral.

Results

Demographics

Details from 115 patients who developed NV while on anticancer treatment were included in the analysis (Table 1). Of these, 13 % (n = 15) experienced more than one NV episode (total number of episodes = 134), the majority (n = 12 of 15) of which were receiving the same treatment upon NV recurrence. The median patient age was 58 years (range, 19–92), and the male to female ratio was 1:2.4.

Concomitant medications and comorbidities

Anticoagulant and inhalant medication use was noted during 22/134 (16 %) and 6/134 (5 %) episodes of NV, respectively. Of the 115 patients, only 4 (3 %) were active smokers, and none were experiencing current URTI. The most common comorbidities were infections (including past viral, bacterial, fungal; n = 16), diabetes (n = 13), hypothyroidism (n = 15), hypertension (n = 36), hyperlipidemia (n = 37), gastroesophageal reflux disease (n = 18), cardiac (heart disease, heart murmur, palpitations, others; n = 17), and depression (n = 14). Underlying hematologic issues included anemia (n = 5), cytopenia (n = 2), leukemia (n = 2), thrombocytopenia (n = 1), and iron deficiency (n = 1), recorded in 10/115 patients (9 %), with 1 patient having two conditions (anemia and thrombocytopenia).

Cancer type and treatment (Table 1)

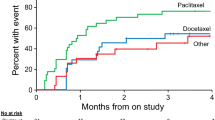

The most common underlying cancer types were lung (non-small cell) (n = 49), breast (n = 22), and colorectal (n = 12). Of the patients undergoing anticancer therapy, 84 % (n = 97) were being treated with a targeted agent, 68 % (n = 78) were receiving an EGFRI-based regimen, while 34 % (n = 39) were on some form of cytotoxic chemotherapy. Erlotinib (n = 35), cetuximab (n = 13), afatinib (n = 9), pertuzumab (n = 8), and panitumumab (n = 8) were the most common EGFRIs that were being administered singly or as doublet therapy, or along with cytotoxic chemotherapy.

Nasal vestibulitis

The seasonal distribution of NV episodes was spring (34 %), winter (33 %), fall (23 %), and summer (10 %) [χ 2(3) = 18.78, P = 0.0003]. In a majority (90 %) of patients, the primary reason for dermatology referral was a skin rash [χ 2(2) = 163.8, P = 0.000]. When additional details pertaining to the 134 episodes of NV were investigated, rash and xerosis were noted in 86 (64) and 77 (57 %) episodes, respectively. In 41 cases (57 %) of NV, rash and xerosis co-occurred in the same patient (Table 2). Symptom severity was mild to moderate (Grade 1/2) (Table 2). The most frequent nasal symptoms during the 134 episodes of NV were crusting (31 %), epistaxis (27 %), xerosis/dry nares/desquamation (7 %), impetigo (5 %), erosions (5 %), pustules (3 %), pain (2 %), erythema (2 %), and irritation (2 %). Folliculitis and furunculosis in the nasal vestibule were noted in 1 case each (1 %). Patients were on anticoagulants only during 5/36 epistaxis episodes.

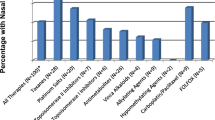

Bacterial cultures from superficial wounds in the nasal vestibule were obtained in 81/134 (60 %) episodes, of which 76 (94 %) were positive for one or more organisms (Fig. 1a and b). In 28 % (21/76) of episodes in which positive culture results were obtained, reports revealed polymicrobial growth. The most frequent organism identified was methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) in 43 % (n = 33) of episodes with positive microbial cultures, with 18 % (n = 6) of MSSA strains reported to be tetracycline-resistant. Laboratory-reported methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) was cultured in 2 episodes of NV. The most frequently isolated Gram-negative bacteria included Serratia marcescens (n = 3) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n = 3). In 49/76 episodes, polymicrobial flora representative of “skin flora” or “pharyngeal flora” was noted. In patients whose other-site rashes were cultured simultaneously (n = 8), organisms were similar in three cases (38 %), with regard to bacterial identity, antibiotic susceptibility, and MIC profile.

Data reflects percentage of bacterial cultures which were positive for one or more organisms (n=76). Reports labeled as skin/pharyngeal flora (including coagulase-negative staphylococci, S. pneumoniae, Corynebacterium sp., and others) are not included. In 21 episodes, culture results were polymicrobial

The antimicrobial MIC distributions for S. aureus isolates are listed in Table 4. Isolates demonstrated resistance to moxifloxacin (n = 30), penicillin (n = 26), clindamycin (n = 4), and levofloxacin (n = 2); and showed intermediate susceptibility to erythromycin (n = 14), tetracycline (n = 5), oxacillin (n = 2), amoxicillin-clavulanate (n = 2), ampicillin-sulbactam (n = 2), cefazolin/cefotaxime/ceftriaxone/chloramphenicol (n = 2), linezolid (n = 1), and imipenem (n = 1).

Most episodes (95 %) of NV were treated with 2 % topical mupirocin, alone (75 %) or in combination with other topical agents (3 %) or oral antibiotics (12 %) (Table 3). In 10 % of treated episodes, other topical agents (e.g., retapamulin, polysporin, chlorhexidine, saline) and oral antibiotics (alone or in combination) were used. Nasal symptoms cleared in 60 % of episodes; the condition did not improve in 6 %, while 34 % had no dermatology follow-up. NV treatment was modified based on susceptibility testing in 14 % (11/76) of NV episodes.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that NV is a clinically significant, yet poorly recognized AE among cancer patients receiving targeted therapies. Abundant clinical data exists on dermatologic AEs to targeted therapies, including rash, paronychia, xerosis, and pruritus, however, secondary dermatologic infections have received little attention [5, 23]. The epidemiology and clinical characteristics of NV remain largely undefined [8, 16]. Furthermore, there is incongruity in its descriptive terminology; the various descriptors include “nasal vestibulitis”, “nasal vestibular furunculosis”, “vestibule furunculosis”, and “nasal infection” [8]. These hindrances may be due to NV’s banal nature, mild symptoms, and infrequent need for treatment in healthy individuals. However, patients treated with targeted therapies frequently develop dermatologic AEs characterized by epidermal disruption and bacterial infection susceptibility [25, 26]. Therefore, these patients may be more likely to develop NV and are more prone to secondary skin infections due to spread of pathogenic organisms from the nares.

In most of our patients, NV occurred simultaneously with rash and/or xerosis, both well-recognized AEs to targeted therapies, especially the EGFRIs. Furthermore, NV can occur with diuretics and isotretinoin use [18], agents known to cause xerosis. Since 68 % of our patients were receiving EGFRI-based regimens, it is reasonable to infer that NV is a potential AE, especially in patients with concomitant rash/xerosis, though there appears to be no correlation with severity (Table 2).

Keratinocytes are dependent on EGFR signaling for normal cutaneous homeostasis and play an important role in innate and adaptive immune responses [10, 27, 28]. During EGFR inhibition, there is decreased barrier and antibiotic protein synthesis in the skin and nasal vestibule. Such disruption in epithelial/follicular barrier integrity can cause susceptibility to infections and microbial colonization [5]. In addition, the interplay between the EGFR, STAT1 and STAT3, and antimicrobial peptides (e.g., cathelicidins, β-defensins) also contributes to skin immunity [29].

Although it has not been determined whether EGFRIs negatively affect immune function, one study demonstrated that erlotinib (the most common targeted agent used in our patients), leads to inhibition of T-cell proliferation and activation [30]. Therefore, we postulate that in patients on erlotinib-based regimens (30 %), altered immune status could have contributed to NV and rash development. Furthermore, because NV may be an infectious process [8], proposing a relationship between EGFRI use and NV is in agreement with earlier work, which found that EGFRI-treated patients had increased susceptibility to cutaneous infections [5]. The authors found that out of 221 EGFRI-treated patients, 38 % developed bacterial, viral, or fungal infections. These findings are important since skin and soft tissue infections can result in bacteremia [31], especially among patients on erlotinib [32, 33], and lead to increased morbidity and mortality.

In our patients, MSSA was the most common pathogen isolated (43 %), consistent with previous observations that S. aureus is the main causative organism in NV [8]. The mean nasal carriage rate of S. aureus is 37.2 % in the general population, and varies significantly among healthcare workers, hospitalized or dialysis patients, drug addicts, and patients with diabetes, HIV, and S. aureus skin lesions [7]. The prevalence of MRSA in our patient cohort (2.6 %) is lower than carriage rates reported among hospitalized patients (3.4 and 7.3 % in two studies) [34, 35]. Since nasal colonization with S. aureus may lead to increased risk of other-site infections [11], and because NV can cause more serious complications (e.g., orbital abscesses, cavernous sinus thrombosis, necrotizing pneumonia) [20, 22, 36–38], we recommend that oncologists inspect patients’ anterior nares and question about symptoms, especially during treatment with EGFRIs among other targeted therapies. Associated medical and hematologic conditions, concomitant anticoagulant or inhalant use, current URTI, and smoking status did not appear to influence the NV development in our subset of patients, most likely due to their low frequency and low-risk characteristics. However, a higher number of NV episodes occurred during winter months, suggesting a role for colder temperatures [39].

We could not correlate S. aureus isolation with NV severity due to lack of existing NV grading scales/scores. However, the frequently noted clinico-morphological features in our patients suggest a temporal scale, which includes mild [xerosis, fissures, erythema, crusting (Fig. 2a), impetiginization], moderate [furunculosis, folliculitis, epistaxis, with/without mild features; Fig. 2b], and severe [edematous and painful nose, with/without mild or moderate features] afflictions. Given that NV is currently a poorly defined entity, these observations may lay the framework for a clinical severity grading scale.

a Honey-colored crusts in the nasal vestibule of a patient receiving panitumumab for metastatic colorectal cancer (also note the background acneiform facial rash). b Furunculosis with xerosis, fissuring, erythema, and crusting, extending onto the upper lip, in a patient being treated with cetuximab for metastatic rectal cancer

As proposed earlier [8, 16], we found that mild/moderate NV responded to intranasal antibiotics (90 %, mupirocin-based), while severe cases required oral antibiotics. Many patients had no dermatology follow-up (34 %); however, NV cleared in 60 % of episodes without complications/hospitalization, perhaps due to timely treatment. For mild cases, saline humidification, nasal emollients, and use of antibiotic ointments (e.g., mupirocin, retapamulin, bacitracin zinc/polymyxin B, chlorhexidine/neomycin) are advised. With the use of emollients (e.g., petroleum jelly, mineral oils) inappropriate for intranasal use, the rare development of lipoid pneumonia must be considered [40, 41]. For severe infections, it is appropriate to administer oral antibiotics based on susceptibility patterns. For recurrences, consider decolonization; however, this approach has limited success; indiscriminate use of intranasal mupirocin may lead to development of resistance [42]. Resistance rates range from 3 to 5 % among MRSA isolates in US/Canadian hospitals; [43] and 1.7 % for MSSA in Latin America [44]. Lastly, in chronic/persistent NV, cutaneous neoplasms (e.g., basal or squamous cell carcinoma) should be ruled out [20].

Our study had several limitations. First, instances where the term “nasal vestibulitis” was not used in the EMR were not captured; we included only cases with a definitive NV diagnosis. Second, all cases were diagnosed by one investigator, introducing the possibility of selection bias. Nevertheless, due to its obscurity and poor awareness of potential complications, our study likely underestimates the incidence of NV in targeted therapy-treated patients. Third, the retrospective nature precluded inclusion of a treatment-regimen matched control group, making it difficult to identify risk factors, incidence data, or culprit anticancer drug(s). Further, although the majority (82 %) received targeted drugs, nine patients received monochemotherapy and 11 were seen for posttreatment follow-up. This suggests that although NV is uncommon in patients receiving conventional chemotherapy or no therapy, there are exceptions. Fourth, culture and sensitivity testing were not done in all patients. Also, though some patients may have been “carriers” of the identified pathogens, baseline microbial culture sensitivity testing is not standard-of-care. Finally, histopathology would have provided better correlation but is impractical.

Conclusion

This is the first study to identify NV as a frequent AE accompanying skin rash/xerosis in cancer patients, primarily during EGFRI treatment, though other targeted and chemotherapeutic agents may also be responsible. Larger-scale systematic studies exploring the epidemiology, etiopathogenesis (including phage typing), clinical features, and management strategies to better define NV, would be natural follow-ups to this initial endeavor. Taken together, our findings are sufficient testimony to NV being clinically significant, and underscore the importance of proactive and careful inspection of the anterior nares along with questioning about related symptoms in cancer patients on treatment. We hope to generate awareness among oncologists, dermatologists, and nurses about this clinically significant yet under-recognized condition.

References

Balagula Y, Lacouture ME, Cotliar JA (2010) Dermatologic toxicities of targeted anticancer therapies. J Support Oncol 8(4):149–161

Rosen AC, Case EC, Dusza SW et al (2013) Impact of dermatologic adverse events on quality of life in 283 cancer patients: a questionnaire study in a dermatology referral clinic. Am J Clin Dermatol 14(4):327–333

Boers-Doets CB, Gelderblom H, Lacouture ME, Epstein JB, Nortier JW, Kaptein AA (2013) Experiences with the FACT-EGFRI-18 instrument in EGFRI-associated mucocutaneous adverse events. Support Care Cancer: Off J Multinat Assoc Support Care Cancer 21(7):1919–1926

Sibaud V, Dalenc F, Chevreau C et al (2011) HFS-14, a specific quality of life scale developed for patients suffering from hand-foot syndrome. Oncologist 16(10):1469–1478

Eilers RE Jr, Gandhi M, Patel JD et al (2010) Dermatologic infections in cancer patients treated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst 102(1):47–53

Gray H (2008) Nose, nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. In: Standring S (ed) Gray’s anatomy: The anatomical basis of clinical practice, 40th edn. Elsevier-Churchill Livingstone, Philadelphia, p 551

Kluytmans J, van Belkum A, Verbrugh H (1997) Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology, underlying mechanisms, and associated risks. Clin Microbiol Rev 10(3):505–520

Dahle KW, Sontheimer RD (2012) The Rudolph sign of nasal vestibular furunculosis: questions raised by this common but under-recognized nasal mucocutaneous disorder. Dermatol Online J 18(3):6

Haug RH (2012) Microorganisms of the nose and paranasal sinuses. Oral Maxillofacial Surg Clinics N Am 24(2):191–196, vii–viii

Percival SL, Emanuel C, Cutting KF, Williams DW (2012) Microbiology of the skin and the role of biofilms in infection. Int Wound J 9(1):14–32

Wertheim HF, Melles DC, Vos MC et al (2005) The role of nasal carriage in Staphylococcus aureus infections. Lancet Infect Dis 5(12):751–762

Talpur R, Bassett R, Duvic M (2008) Prevalence and treatment of Staphylococcus aureus colonization in patients with mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome. Br J Dermatol 159(1):105–112

Nguyen V, Huggins RH, Lertsburapa T et al (2008) Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and Staphylococcus aureus colonization. J Am Acad Dermatol 59(6):949–952

Kullander J, Forslund O, Dillner J (2009) Staphylococcus aureus and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev: Publ Am Assoc Cancer Res Cosponsored Am Soc Prev Oncol 18(2):472–478

Becker K, von Eiff C (2011) Staphylococcus, micrococcus, and other catalase-positive cocci. In: Bernard KA, Dumler JS, Petti CA, Richter SS, Vandamme PAR (eds) Manual of clinical microbiology. Vol 1, 10th edn. ASM Press, Washington

Rambur B, Winbourn MW (1994) Recognizing nasal vestibulitis in the primary care setting. Nurse Pract. 19(12):22, 25–26

Robson AK, Burge SM, Millard PR (1992) Nasal mucosal involvement in lupus erythematosus. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 17(4):341–343

Williams RE, Doherty VR, Perkins W, Aitchison TC, Mackie RM (1992) Staphylococcus aureus and intra-nasal mupirocin in patients receiving isotretinoin for acne. Br J Dermatol 126(4):362–366

Kojima Y, Tsuzuki K, Takebayashi H, Oka H, Sakagami M (2013) Therapeutic evaluation of outpatient submucosal inferior turbinate surgery for patients with severe allergic rhinitis. Allergol Int: Off J Japan Soc Allergol

Önerci TM (2010) Nasal vestibulitis and nasal furunculosis and mucormycosis. In: Önerci TM, (ed). Diagnosis in Otorhinolaryngology. Vol VII: Springer

von Schoenberg M, Robinson P, Ryan R (1992) The morbidity from nasal splints in 105 patients. Clini Otolaryngol Allied Sci 17(6):528–530

DiNubile MJ (1988) Septic thrombosis of the cavernous sinuses. Arch Neurol 45(5):567–572

Eames T, Grabein B, Kroth J, Wollenberg A (2010) Microbiological analysis of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor therapy-associated paronychia. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol: JEADV 24(8):958–960

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility testing; Twenty-Second Informational Supplement. CLSI document M100-S22. 2012. Vol 32 (3). Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute

Lichtenberger BM, Gerber PA, Holcmann M et al (2013) Epidermal EGFR controls cutaneous host defense and prevents inflammation. Sci Transl Med 5(199):199ra111

Mascia F, Lam G, Keith C et al (2013) Genetic ablation of epidermal EGFR reveals the dynamic origin of adverse effects of anti-EGFR therapy. Sci Transl Med 5(199):199ra110

Sugita K, Kabashima K, Atarashi K, Shimauchi T, Kobayashi M, Tokura Y (2007) Innate immunity mediated by epidermal keratinocytes promotes acquired immunity involving Langerhans cells and T cells in the skin. Clin Exp Immunol 147(1):176–183

Gutowska-Owsiak D, Ogg GS (2012) The epidermis as an adjuvant. J Investig Dermatol 132(3 Pt 2):940–948

Niyonsaba F, Ushio H, Nakano N et al (2007) Antimicrobial peptides human beta-defensins stimulate epidermal keratinocyte migration, proliferation and production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. J Investig Dermatol 127(3):594–604

Luo Q, Gu Y, Zheng W et al (2011) Erlotinib inhibits T-cell-mediated immune response via down-regulation of the c-Raf/ERK cascade and Akt signaling pathway. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 251(2):130–136

Wilson J, Guy R, Elgohari S et al (2011) Trends in sources of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteraemia: data from the national mandatory surveillance of MRSA bacteraemia in England, 2006–2009. J Hosp Infect 79(3):211–217

Grenader T, Gipps M, Goldberg A (2008) Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia secondary to severe erlotinib skin toxicity. Clin Lung Cancer 9(1):59–60

Li J, Peccerillo J, Kaley K, Saif MW (2009) Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia related with erlotinib skin toxicity in a patient with pancreatic cancer. JOP: J Pancreas 10(3):338–340

Davis KA, Stewart JJ, Crouch HK, Florez CE, Hospenthal DR (2004) Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) nares colonization at hospital admission and its effect on subsequent MRSA infection. Clin Infect Dis: Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am 39(6):776–782

Hidron AI, Kourbatova EV, Halvosa JS et al (2005) Risk factors for colonization with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in patients admitted to an urban hospital: emergence of community-associated MRSA nasal carriage. Clin Infect Dis: Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am 41(2):159–166

Mahasin Z, Saleem M, Quick CA (2001) Multiple bilateral orbital abscesses secondary to nasal furunculosis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 58(2):167–171

Laifer G, Frei R, Adler H, Fluckiger U (2006) Necrotising pneumonia complicating a nasal furuncle. Lancet 367(9522):1628

Sethi P, Jones ST, Valenzuela AA (2013) Septic cavernous sinus thrombosis with diffuse spread leading to cerebral ischemia. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands)

Veach HO (1940) Aluminum chlorid in folliculitis of the nose. Cal West Med 52(2):76

Wright BA, Jeffrey PH (1990) Lipoid pneumonia. Semin Respir Infect 5(4):314–321

Sharma A, Ohri S, Bambery P, Singh S (2006) Idiopathic endogenous lipoid pneumonia. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci 48(2):143–145

Patel JB, Gorwitz RJ, Jernigan JA (2009) Mupirocin resistance. Clini Infect Dis: Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am 49(6):935–941

Hetem DJ, Bonten MJ (2013) Clinical relevance of mupirocin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. J Hosp Infect 85(4):249–256

Gales AC, Andrade SS, Sader HS, Jones RN (2004) Activity of mupirocin and 14 additional antibiotics against staphylococci isolated from Latin American hospitals: report from the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program. J Chemother (Florence, Italy) 16(4):323–328

Acknowledgments

We thank the MSKCC Information Systems’ data delivery group (DataLine), especially Joseph Schmeltz (Data Administrator) and Stuart Gardos (Project Manager), for the assistance with data acquisition and Bernadette Murphy (Medical Photographer) for clinical photographs.

Conflicts of interest

JNR, VRB, MK, NEB, YT, and TV have nothing to disclose. CBB-D has a speaking, consultant, or advisory role with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eusa Pharma, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Serono, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche. MEL has a speaking, consultant or advisory role with Advancell, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Augmentium, Aveo, Bayer, Berg Pharma, Biopharm Communications, Boehringer Ingelheim, Brickell Biotech, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Clinical Assistance Programs, Clinical Care Options, EMD Serono, Envision Communications, Foamix, Galderma, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Helsinn, Institute for Medical Education and Research, Integro-MC, Lindi Skin, Medscape, Medtrend International, Merck, Nerre Therapeutics, Novartis, Novocure, Oncology Specialty Group, OSI Pharmaceuticals, Permanyer, Physicians Education Resource, Pierre Fabre, Pfizer, Reata Pharmaceuticals, Roche, Sandoz, Sanofi Aventis, and Threshold Pharmaceuticals.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

These authors, Janelle N. Ruiz and Viswanath Reddy Belum, contributed equally to this manuscript.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ruiz, J.N., Belum, V.R., Boers-Doets, C.B. et al. Nasal vestibulitis due to targeted therapies in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 23, 2391–2398 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2580-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2580-x