Abstract

Purpose

Parents’ stress levels are high prior to their child’s hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) and during transplant hospitalization, usually abating after discharge. Nevertheless, a subgroup of parents continues to experience frequent anxiety and mood disruption, the causes of which are not well understood. The purpose of this study was to assess whether clinical complications of HSCT could explain variation in parents’ recovery of emotional functioning.

Methods

Pediatric HSCT recipients (n = 165) aged 5–18 and their parents were followed over the first year post-transplant. Health-related quality of life assessments and medical chart reviews were performed at each time period (baseline, 45 days, 3, 6, and 12 months). We tested the association between clinical complications [acute and chronic graft versus host disease (aGVHD and cGVHD), organ toxicity, and infection] and longitudinally measured parental emotional functioning, as assessed by the Child Health-Ratings Inventories. The models used maximum likelihood estimation with repeated measures.

Results

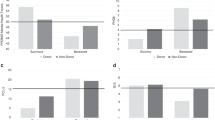

In adjusted analyses covering the early time period (45 days and 3 months), aGVHD grade ≥2, intermediate or poor organ toxicity, and systemic infection were associated with decreases in mean parental emotional functioning of 5.2 (p = 0.086), 5.8 (p = 0.052), and 5.1 (p = 0.023) points, respectively. In the later time period (6 and 12 months), systemic infection was associated with a decrease of 20 points (p < 0.0001). cGVHD was not significantly associated.

Conclusions

When children experience clinical complications after HSCT, parental emotional functioning can be impacted. Intervening at critical junctures could mitigate potential negative consequences for parents and their children.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Packman W, Weber S, Wallace J, Bugescu N (2010) Psychological effects of hematopoietic SCT on pediatric patients, siblings and parents: a review. Bone Marrow Transplant 45(7):1134–1146. doi:10.1038/bmt.2010.74

Jobe-Shields L, Alderfer M, Barrera M, Vannatta K, Currier J, Phipps S (2009) Parental depression and family environment predict distress in children prior to stem-cell transplantation. J Dev Behav Pediatr 30(2):140–146. doi:10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181976a59

Copelan EA (2006) Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. N Engl J Med 354(17):1813–1826. doi:10.1056/NEJMra052638

Downey G, Coyne JC (1990) Children of depressed parents: an integrative review. Psychol Bull 108(1):50–76. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.108.1.50

Vrijmoet-Wiersma CM, Egeler RM, Koopman HM, Norberg AL, Grootenhuis MA (2009) Parental stress before, during, and after pediatric stem cell transplantation: a review article. Support Care Cancer 17(12):1435–1443. doi:10.1007/s00520-009-0685-4

Parsons S, Terrin N, Ratichek S, Tighiouart H, Recklitis C, Chang G (2009) Trajectories of HRQL following pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) [abstract]. International Society for Quality of Life Research Annual Conference. Springer, New Orleans, pp A–44, Abstract #1420

Parsons SK, Shih MC, Mayer DK, Barlow SE, Supran SE, Levy SL, Greenfield S, Kaplan SH (2005) Preliminary psychometric evaluation of the Child Health Ratings Inventories (CHRIs) and Disease-Specific Impairment Inventory-HSCT (DSII-HSCT) in parents and children. Qual Life Res 14(6):1613–1625. doi:10.1007/s11136-005-1004-2

Parsons SK, Shih MC, DuHamel KN, Ostroff J, Mayer DK, Austin J, Martini DR, Williams SE, Mee L, Sexson S et al (2006) Maternal perspectives on children’s health-related quality of life during the first year after pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplant. J Pediatr Psychol 31(10):1100–1115. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsj078

Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD (1992) The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 30(6):473–483. doi:10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002

Rodday A, Terrin N, Chang G, Parsons S (2012) Performance of the parent emotional functioning (PREMO) screener in parents of children undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Qual Life Res. doi:10.1007/s11136-012-0240-5

National Cancer Institute (2009) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4.0 (CTCAE). National Cancer Institute, Bethesda MD. www.cancer.gov

Shulman H, Sullivan K, Weiden P, McDonald G, Striker G, Sale G, Hackman R, Tsoi M, Storb R, Thomas E (1980) Chronic graft-versus-host disease syndrome in man. A long-term clinicopathologic study of 20 Seattle patients. Amer J Med 69(1):204–217. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(80)90380-0

Glucksberg H, Storb R, Fefer A, Buckner CD, Neiman PE, Clift RA, Lerner KG, Thomas ED (1974) Clinical manifestations of graft-versus-host disease in human recipients of marrow from HL-A-matched sibling donors. Transplantation 18(4):295–304. doi:10.1097/00007890-197410000-00001

Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, Klingemann HG, Beatty P, Hows J, Thomas ED (1995) 1994 Consensus Conference on Acute GVHD Grading. Bone Marrow Transplant 15(6):825–828

Bearman SI, Appelbaum FR, Buckner CD, Petersen FB, Fisher LD, Clift RA, Thomas ED (1988) Regimen-related toxicity in patients undergoing bone marrow transplantation. J Clin Oncol 6(10):1562–1568

Hedeker D, Gibbons R (1997) Application of random-effects pattern-mixture models for missing data in longitudinal studies. Psychol Methods 2(1):64–78. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.2.1.64

Manne S, DuHamel K, Ostroff J, Parsons S, Martini DR, Williams SE, Mee L, Sexson S, Austin J, Winkel G et al (2003) Coping and the course of mother’s depressive symptoms during and after pediatric bone marrow transplantation. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 42(9):1055–1068. doi:10.1097/01.CHI.0000070248.24125.C0

Nelson AE, Miles MS, Belyea MJ (1997) Coping and support effects on mothers’ stress responses to their child’s hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 14(4):202–212. doi:10.1177/104345429701400404

Dermatis H, Lesko LM (1990) Psychological distress in parents consenting to child’s bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 6(6):411–417

Rodrigue JR, MacNaughton K, Hoffmann RG III, Graham-Pole J, Andres JM, Novak DA, Fennell RS (1997) Transplantation in children. A longitudinal assessment of mothers’ stress, coping, and perceptions of family functioning. Psychosomatics 38(5):478–486. doi:10.1016/S0033-3182(97)71425-7

Streisand R, Rodrigue JR, Houck C, Graham-Pole J, Berlant N (2000) Brief report: parents of children undergoing bone marrow transplantation: documenting stress and piloting a psychological intervention program. J Pediatr Psychol 25(5):331–337. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/25.5.331

Phipps S, Dunavant M, Lensing S, Rai SN (2005) Psychosocial predictors of distress in parents of children undergoing stem cell or bone marrow transplantation. J Pediatr Psychol 30(2):139–153. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsi002

Manne S, Nereo N, DuHamel K, Ostroff J, Parsons S, Martini R, Williams S, Mee L, Sexson S, Lewis J et al (2001) Anxiety and depression in mothers of children undergoing bone marrow transplant: symptom prevalence and use of the Beck depression and Beck anxiety inventories as screening instruments. J Consult Clin Psychol 69(6):1037–1047. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.69.6.1037

Warner CM, Ludwig K, Sweeney C, Spillane C, Hogan L, Ryan J, Carroll W (2011) Treating persistent distress and anxiety in parents of children with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 28(4):224–230. doi:10.1177/1043454211408105

Funding

This study was supported by American Cancer Society grant RSGPB-02-186-01-PBP (Parsons, PI) and NIH grant R01 CA119196 (Parsons, PI).

Conflict of interest

We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

Bearman maximum overall toxicity:

Regimen-related, non-hematologic toxicity during the first 100 days following HSCT was evaluated for all patients using the Bearman Toxicity Scale, which is widely used in HSCT-related clinical studies. [15] The scale utilizes a four-point scale from 0–3, (range, absent to severe, end-organ damage) for each of eight organ systems [e.g., cardiac, bladder, renal, pulmonary, hepatic, CNS (central nervous system), stomatitis, and GI (gastrointestinal)]. Maximum overall toxicity is classified as “good,” “intermediate,” or “poor,” based on the combination of toxicity grading for each organ system. “Good” is defined as ≤grade 1 in all organ systems or maximum toxicity of 2 in ≤2 organ systems. “Intermediate” is defined as maximum toxicity of 2 in ≥3 organ systems, and “poor” is defined as maximum toxicity of 3 in at least one organ system.

Appendix 2

Participating institutions and site investigators in the journeys to recovery study

Central Project Staff

Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA: Susan K. Parsons, MD, MRP, Principal Investigator

Site Principal Investigators

Baylor College of Medicine/Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, TX: Lynette Harris, PhD and Robert A. Krance, MD, Principal Investigators

City of Hope, Duarte, CA: Sunita Patel, PhD, Principal Investigator; Joseph Rosenthal, MD, Site Consultant

Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA: Christopher Recklitis, PhD, MPH, Principal Investigator

Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA: Karen L. Syrjala, PhD, Principal Investigator; Jean Sanders, MD, Co-Principal Investigator

Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI: Mary Jo Kupst, PhD, Principal Investigator; Kristin Bingen, PhD and James Casper, MD, Co-Principal Investigators

University of Pittsburgh/Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA: Robert B. Noll, PhD, Principal Investigator; Linda J. Ewing, PhD, RN, Co-Principal Investigator

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Terrin, N., Rodday, A.M., Tighiouart, H. et al. Parental emotional functioning declines with occurrence of clinical complications in pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Support Care Cancer 21, 687–695 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-012-1566-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-012-1566-9