Abstract

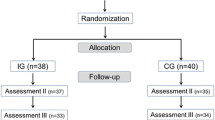

Pediatricians’ job performance, work engagement, and job satisfaction are essential for both the individual physician and quality of care for their little patients and parents. Therefore, it is important to maintain or possibly augment pediatricians’ individual and professional competencies. In this study, we developed and implemented a psychosocial competency training (PCT) teaching different psychosocial competencies and stress coping techniques. We investigated (1) the influence of the PCT on work-related characteristics: stress perception, work engagement, job satisfaction and (2) explored pediatricians’ outcomes and satisfaction with PCT. Fifty-four junior physicians working in pediatric hospital departments participated in the training and were randomized in an intervention (n = 26) or a control group (n = 28). In the beginning, at follow-up 1 and 2, both groups answered a self-rated questionnaire on perceived training outcomes and work-related factors. The intervention group showed that their job satisfaction significantly increased while perceived stress scores decreased after taking part in the PCT. No substantial changes were observed with regard to pediatricians’ work engagement. Participating physicians evaluated PCT with high scores for training design, content, received outcome, and overall satisfaction with the training.

Conclusion: Professional psychosocial competency training could improve junior pediatricians’ professional skills, reduce stress perception, increase their job satisfaction, and psychosocial skills. In addition, this study indicates that the PCT is beneficial to be implemented as a group training program for junior pediatricians at work.

What is Known: • Junior pediatricians often report experiencing high levels of job strain and little supervisory support. • High levels of job demands make pediatricians vulnerable for mental health problems and decreased work ability. |

What is New: • Development, implementation, and evaluation of a psychosocial competency training for junior pediatricians working in clinical settings • Psychosocial competency training has the potential to improve pediatricians’ psychosocial skills and perceptions of perceived work-related stress and job satisfaction. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- b:

-

Beta weight

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COPSOQ:

-

Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire

- N:

-

Numbers

- M:

-

Mean

- MD:

-

Median

- P:

-

Probability

- PCT:

-

Psychosocial competency training

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- UWES:

-

Utrecht Work Engagement Scale

References

Ayres J, Malouff JM (2007) Problem-solving training to help workers increase positive affect, job satisfaction, and life satisfaction. Eur J Work Organ Psychol 16:279–294

Bernburg M, Vitzthum K, Groneberg DA, Mache S (2016) Physicians’ occupational stress, depressive symptoms and work ability in relation to their working environment: a cross-sectional study of differences among medical residents with various specialties working in German hospitals. BMJ Open 15:6

Bourbonnais R, Brisson C, Vinet A, Vezina M, Abdous B, Gaudet M (2006a) Effectiveness of a participative intervention on psychosocial work factors to prevent mental health problems in a hospital setting. Occup Environ Med 63:335–342

Bourbonnais R, Brisson C, Vinet A, Vézina M, Lower A (2006b) Development and implementation of a participative intervention to improve the psychosocial work environment and mental health in an acute care hospital. Occup Environ Med 63:326–334

Brooks SK, Chalder T, Gerada C (2011) Doctors vulnerable to psychological distress and addictions: treatment from the Practitioner Health Programme. J Ment Health 20:157–164

Buchberger B, Heymann R, Huppertz H, Friepörtner K, Pomorin N, Wasem J (2011) The effectiveness of interventions in workplace health promotion as to maintain the working capacity of health care personal. GMS Health Technol Assess 1

Burton NW, Pakenham KI, Brown WJ (2008) Feasibility and effectiveness of psychosocial resilience training: a pilot study of the READY program. Psychol Health Med 15:266–277

Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK (1989) Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. J Pers Soc Psychol 56:267–283

Czabała C, Charzyńska K, Mroziak B (2011) Psychosocial interventions in workplace mental health promotion: an overview. Health Promot Int 26(Suppl 1):i70–i84. doi:10.1093/heapro/dar1050

Goldhagen BE, Kingsolver K, Stinnett SS, Rosdahl JA (2015) Stress and burnout in residents: impact of mindfulness-based resilience training. Adv Med Educ Pract 25:525–532

Holton MK, Barry AE, Chaney JD (2015) Employee stress management: an examination of adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies on employee health. Work

Irving JA, Dobkin PL, Park J (2009) Cultivating mindfulness in health care professionals: a review of empirical studies of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR. Complement Ther Clin Pract 15:61–66

Kirkpatrick DL, Kirkpatrick DJ (2006) Evaluating training programs: the four levels. Berrett-Koehler Publishers

Krasner MS, Epstein RM, Beckman H (2009) Association of an educational program in mindful communication with burnout, empathy, and attitudes among primary care physician. JAMA 302:1284–1293

Kristensen T, Hannerz H, Høgh A, Borg V (2005) The Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ)—a tool for the assessment and improvement of the psychosocial work environment. Scand J Work Environ Health 31:438–449

Lagerveld SE, Blonk RW, Brenninkmeijer V, Wijngaards-de Meij L, Schaufeli WB (2012) Work-focused treatment of common mental disorders and return to work: a comparative outcome study. J Occup Health Psychol 17:220–234

Leppin AL, Gionfriddo MR, Sood A, Montori VM, Erwin PJ, Zeballos-Palacios C, Bora PR, Dulohery MM, Brito JP, Boehmer KR, Tilburt JC (2014) The efficacy of resilience training programs: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-3-20

Levenstein S, Prantera C, Varvo V, Scribano ML, Berto E, Luzi C (1993) Development of the Perceived Stress Questionnaire: a new tool for psychosomatic research. J Psychsom Res 37:19–32

Li J, Weigl M, Glaser J, Petru R, Siegrist J, Angerer P (2013) Changes in psychosocial work environment and depressive symptoms: a prospective study in junior physicians. Am J Ind Med 56:1414–1422

Mache S, Vitzthum K, Nienhaus A, Klapp BF, Groneberg DA (2009) Physicians’ working conditions and job satisfaction: does hospital ownership in Germany make a difference? BMC Health Serv Res 9:148

McCue JD, Sachs CL (1991) A stress management workshop improves residents’ coping skills. Arch Intern Med 151:2273–2277

Nuebling M, Hasselhorn HM (2010a) The Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire in Germany: from the validation of the instrument to the formation of a job-specific database of psychosocial factors at work. Scand J Public Health 38:120–124

Puskar KR, Sereika S, Tusaie-Mumford K (2003) Effect of the Teaching Kids to Cope (TKC) program on outcomes of depression and coping among rural adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs 16:71–80

Rabe M, Giacomuzzi S, Nübling M (2012) Psychosocial workload and stress in the workers’ representative. BMC Public Health 12:909

Ramirez AJ, Graham J, Richards MA, Cull A, Gregory WM (1996) Mental health of hospital consultants: the effects of stress and satisfaction at work. Lancet 347:724–728

Sautier LP, Scherwath A, Weis J, Sarkar S, Bosbach M, Schendel M, Ladehoff N, Koch U, Mehnert A (2015) Assessment of work engagement in patients with hematological malignancies: psychometric properties of the German version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale 9 (UWES-9). Rehabilitation 54:297–303

Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB (2003) Utrecht Work Engagement Scale: preliminary manual. Occupational Health Psychology Unit, Utrecht University, Utrecht Netherlands. pp 1-58

Sen S, Kranzler HR, Krystal JH, Speller H, Chan G, Gelernter J, Guille C (2010) A prospective cohort study investigating factors associated with depression during medical internship. Arch Gen Psychiatry 67:557–565

Sepällä P, Mauno S, Feldt T (2009) The construct validity of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale: multisample and longitudinal evidence. J Happiness Stud 10:459–481

Shapiro SL, Astin JA, Bishop SR (2005) Mindfulness-based stress reduction for health care professionals: results from a randomized trial. Int J Stress Manag 12:164–176

Sood A, Prasad K, Schroeder D, Varkey P (2011) Stress management and resilience training among Department of Medicine faculty: a pilot randomized clinical trial. J Gen Intern Med 26:858–861

Strijk JE, Proper KI, van Mechelen W, van der Beek AJ (2013) Effectiveness of a worksite lifestyle intervention on vitality, work engagement, productivity, and sick leave: results of a randomized controlled trial. Scand J Work Environ Health 39:66–75

Tan L, Wang MJ, Modini M, Joyce S, Mykletun A, Christensen H, Harvey SB (2014) Preventing the development of depression at work: a systematic review and meta-analysis of universal interventions in the workplace. BMC Med 12:74

van Berkel J, Boot CR, Proper KI, Bongers PM, van der Beek AJ (2014) Effectiveness of a worksite mindfulness-related multi-component health promotion intervention on work engagement and mental health: results of a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 28:1

Weigl M, Müller A, Angerer P, Hoffmann F (2014) Workflow interruptions and mental workload in hospital pediatricians: an observational study. BMC Health Serv Res 24:433

Weigl M, Schneider A, Hoffmann F, Angerer P (2015) Work stress, burnout, and perceived quality of care: a cross-sectional study among hospital pediatricians. Eur J Pediatr 174:1237–1246

West CP, Dyrbye LN, Rabatin JT, Call TG, Davidson JH, Multari A, Romanski SA, Hellyer JMH, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TF (2014) Intervention to promote physician well-being, job satisfaction, and professionalism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 174:527–533

Zimber A, Gregersen S, Kuhnert S, Nienhaus A (2010) Workplace health promotion through human resources development part I: development and evaluation of qualification programme for prevention of psychic stresses. Gesundheitswesen 72:209–215

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Karin Vitzthum for language editing and proof-reading.

Authors’ contribution

SM, MB, and LB designed the study. MB, LB, and SM performed the investigation. SM and MB analyzed the data. SM and MB wrote the manuscript. SM, MB, LB, and DG interpreted the data and contributed substantially to its revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was granted by the Free University Berlin. The study is in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individuals participants included in this study.

Funding

No funding support.

Additional information

Communicated by Jaan Toelen

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bernburg, M., Baresi, L., Groneberg, D. et al. Does psychosocial competency training for junior physicians working in pediatric medicine improve individual skills and perceived job stress. Eur J Pediatr 175, 1905–1912 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-016-2777-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-016-2777-8