Abstract

There are many theories that explain how route knowledge is acquired. We examined here if the sequence of elements that are part of a route can become integrated into a single unit, to the extent that the processing of individual transitions may only be relevant in the context of this entire unit. In Experiments 1 and 2, participants learned a route for ten blocks. Subsequently, at test they were intermittently exposed to the same training route along with a novel route which contained partial overlap with the original training route. Results show that the very same stimulus, appearing in the very same location, requiring the very same response (e.g., left turn), was responded to significantly faster in the context of the original training route than in the novel route. In Experiment 3, we employed a modified paradigm containing landmarks and two matched routes which were both substantially longer and contained a greater degree of overlap than the routes in Experiments 1 and 2. Results were replicated, namely, the same overlapping route segment, common to both routes, was performed significantly slower when appearing in the context of a novel than the original route. Furthermore, the difference between the overlapping segments was similar to the difference observed for the non-overlapping segments, i.e., an old route segment in the context of a novel route was processed as if it were an entirely novel segment. We discuss the results in relation to binding, chunking, and transfer effects, as well as potential practical implications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

BLOCK (upper-case) refers to a segment connecting two intersections, whilst block (lower-case) refers to a group of experimental trials).

As explained above, block (lower-case) refers to a group of trials and not route segment (BLOCKS).

References

Anderson, J. R., & Matessa, M. (1997). A production system theory of serial memory. Psychological Review, 104(4), 728.

Bailenson, J. N., Shum, M. S., & Uttal, D. H. (2000). The initial segment strategy: A heuristic for route selection. Memory and Cognition, 28(2), 306–318.

Bo, J., & Seidler, R. D. (2009). Visuospatial working memory capacity predicts the organization of acquired explicit motor sequences. Journal of Neurophysiology, 101, 3116–3125.

Boucher, L., & Dienes, Z. (2003). Two ways of learning associations. Cognitive Science, 27, 807–842.

Cleeremans, A., & McClelland, J. L. (1991). Learning the structure of event sequences. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 120, 235–253.

Elman, J. L. (1990). Finding structure in time. Cognitive Science, 14, 179–211.

Epstein, R. A., & Vass, L. K. (2014). Neural systems for landmark-based wayfinding in humans. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 369, 20120533.

Foo, P., Duchon, A., Warren, W. H., Jr., & Tarr, M. J. (2007). Humans do not switch between path knowledge and landmarks when learning a new environment. Psychological Research, 71(3), 240–251.

Fu, E., Bravo, M., & Roskos, B. (2015). Single-destination navigation in a multiple-destination environment: a new “later-destination attractor” bias in route choice. Memory and cognition, 43(7), 1043–1055.

Ganor-Stern, D., Plonsker, R., Perlman, A., & Tzelgov, J. (2013). Are all changes equal? Comparing early and late changes in sequence learning. Acta Psychologica, 144(1), 180–189.

Gillner, S., & Mallot, H. A. (1998). Navigation and acquisition of spatial knowledge in a virtual maze. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 10, 445–463.

Giroux, I., & Rey, A. (2009). Lexical and sub-lexical units in speech perception. Cognitive Science, 33, 260–272.

Goldstone, R. L. (2000). Unitization during category learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 26, 86–112.

Gopher, D., Well, M., & Bareket, T. (1994). Transfer of skill from a computer game trainer to flight. Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 36(3), 387–405.

Green, C. S., & Bavelier, D. (2008). Exercising your brain: a review of human brain plasticity and training-induced learning. Psychology and aging, 23(4), 692–701.

Hochmair, H. H., & Frank, A. U. (2002). Influence of estimation errors on wayfinding-decisions in unknown street networks—analyzing the least angle strategy. Spatial Cognition and Computation, 2(4), 283–313.

Ishikawa, T., Fujiwara, H., Imai, O., & Okabe, A. (2008). Wayfinding with a GPS-based mobile navigation system: A comparison with maps and direct experience. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 28(1), 74–82.

Karni, A., & Sagi, D. (1991). Where practice makes perfect in texture discrimination: Evidence for primary visual cortex plasticity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 88(11), 4966–4970.

Klippel, A., Tappe, H., & Habel, C. (2003). Pictorial representations of routes: Chunking route segments during comprehension. In C. Freksa, W. Brauer, C. Habel, K. F. Wender (Eds.), Spatial Cognition III. Routes and Navigation, Human Memory and Learning, Spatial Representation and Spatial Learning (pp. 11–33). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

Knowlton, B. J., & Squire, L. R. (1996). Artificial grammar learning depends on implicit acquisition of both abstract and exemplar-specific information. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 22, 169–181.

Kuipers, B. (1978). Modeling spatial knowledge. Cognitive Science, 2, 129–153.

Kuipers, B. (2000). The spatial semantic hierarchy. Artificial Intelligence, 19, 191–233.

Kuipers, B., Tecuci, D. G., & Stankiewicz, B. J. (2003). The skeleton in the cognitive map: A computational and empirical exploration. Environment and Behavior, 35(1), 81–106.

Li, B., Zhu, K., Zhang, W., Wu, A., & Zhang, X. (2013). A comparative study of two wayfinding aids with simulated driving tasks—GPS and a dual-scale exploration aid. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 29(3), 169–177.

Maguire, E. A., Woollett, K., & Spiers, H. J. (2006). London taxi drivers and bus drivers: a structural MRI and neuropsychological analysis. Hippocampus, 16(12), 1091–1101.

Mayr, U. (1996). Spatial attention and implicit sequence learning: Evidence for independent learning of spatial and nonspatial sequences. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 22, 350–364.

Meilinger, T. (2008). The network of reference frames theory: A synthesis of graphs and cognitive maps. In C. Freksa, N. Newcombe, P. Gärdenfors, & S. Wölfl (Eds.), Spatial cognition VI: Learning, reasoning, and talking about space (pp. 44–360). Berlin: Springer.

Meilinger, T., Frankenstein, J., & Bülthoff, H. H. (2014). When in doubt follow your nose—a wayfinding strategy. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1363.

Miller, G. A. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information. The Psychological Review, 63, 81–97.

Newell, A., & Simon, H. A. (1972). Human problem solving. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Pashler, H., & Baylis, G. C. (1991). Procedural learning: II. Intertrial repetition effects in speeded-choice tasks. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 17(1), 33–48.

Perlman, A., Hoffman, Y., Tzelgov, J., Pothos, E. M., & Edwards, D. J. (2016). The notion of contextual locking: Previously learnt items are not accessible as such when appearing in a less common context. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 69(3), 410–431.

Perlman, A., Pothos, E. M., Edwards, D., & Tzelgov, J. (2010). Task-relevant chunking in sequence learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 36, 649–661.

Perlman, A., & Tzelgov, J. (2006). Interactions between encoding and retrieval in the domain of sequence-learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 32(1), 118–130

Perruchet, P., & Vinter, A. (2002). The self-organizing consciousness. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 25, 297–388.

Pothos, E. M., & Wolff, J. G. (2006). The simplicity and power model for inductive inference. Artificial Intelligence Review, 26(3), 211-225.

Rhodes, B. J., Bullock, D., Verwey, W. B., Averbeck, B. B., & Page, M. P. A. (2004). Learning and production of movement sequences: Behavioral, neurophysiological, and modeling perspectives. Human Movement Science, 23, 699–746.

Richter, K.-F., & Klippel, A. (2005). A model for context-specific route directions. In C. Freksa, M. Knauff, B. Krieg-Brückner, B. Nebel, & T. Barkowsky (Eds.), Spatial cognition IV. Reasoning, action, interaction (pp. 58–78). Berlin: Springer.

Rosenbaum, D. A., Hindorff, V., & Munro, E. M. (1987). Scheduling and programming of rapid finger sequences: Tests and elaborations of the hierarchical editor model. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 13, 193–203.

Rosenbaum, D. A., Kenny, S. B., & Derr, M. A. (1983). Hierarchical control of rapid movement sequences. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 9, 86–102.

Rumelhart, D. E., & McClelland, J. L. (1986). Parallel distributed processing. Foundations (Vol. 1). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Sakai, K., Kitaguchi, K., & Hikosaka, O. (2003). Chunking during human visuomotor sequence learning. Experimental Brain Research, 152, 229–242.

Sakellaridi, S., Christova, P., Christopoulos, V. N., Vialard, A., Peponis, J., & Georgopoulos, A. P. (2015). Cognitive mechanisms underlying instructed choice exploration of small city maps. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 9, 1–12

Sanchez, D. J., Yarnik, E. N., & Reber, P. J. (2014). Quantifying transfer after perceptual-motor sequence learning: how inflexible is implicit learning? Psychological Research, 79(2), 327–343.

Schwarb, H., & Schumacher, E. H. (2010). Implicit sequence learning is represented by stimulus–response rules. Memory and Cognition, 38, 677–688.

Seidler, R. D., Bo, J., & Anguera, J. A. (2012). Neurocognitive contributions to motor skill learning: The role of working memory. Journal of Motor Behavior, 44(6), 445–453.

Simon, H. A., & Barenfeld, M. (1969). Information-processing analysis of perceptual processes in problem solving. Psychological Review, 76, 473–483.

Strickrodt, M., O’Malley, M., & Wiener, J. M. (2015). This place looks familiar—how navigators distinguish places with ambiguous landmark objects when learning novel routes. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1–12.

Vallacher, R. R., & Wegner, D. M. (1987). What do people think they’re doing? Action identification and human behavior. Psychological review, 94(1), 3–15.

Verwey, W. B. (1999). Evidence for a multi-stage model of practice in a sequential movement task. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 25, 1693–1708.

Verwey, W. B. (2001). Concatenating familiar movement sequence: The versatile cognitive processor. Acta Psychologica, 106, 69–95.

Verwey, W. B., Lammens, R., & van Honk, J. (2002). On the role of the SMA in the discrete sequence production task. A TMS study. Neuropsychologia, 40, 1268–1276.

Verwey, W. B., Shea, C. H., & Wright, D. L. (2015). A cognitive framework for explaining serial processing and sequence execution strategies. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 22(1), 54–77.

Verwey, W. B., & Wright, D. L. (2014). Learning a keying sequence you never executed: Evidence for independent associative and motor chunk learning. Acta psychologica, 151, 24–31.

Werner, S., Krieg-Brückner, B., & Herrmann, T. (2000). Modelling navigational knowledge by route graphs. In C. Freksa, W. Brauer, C. Habel, & K. F. Wender (Eds.), Spatial cognition II: Integrating abstract theories, empirical studies, formal methods, and practical applications (pp. 295–316). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

Willingham, D. B., Wells, L. A., Farrell, J. M., & Stemwedel, M. E. (2000). Implicit motor sequence learning is represented in response locations. Memory and Cognition, 28, 366–375.

Ziessler, M. (1998). Response–effect learning as a major component of implicit serial learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 24, 962–978.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was not funded.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics

All procedures performed in the reported studies were in accordance with the institutional ethical committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

A. Perlman and Y. Hoffman contributed equally to this publication (order of authorship for these authors was determined by coin toss).

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

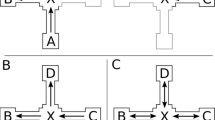

Simple algorithms for modeling sequence learning: We ask what kind of simple algorithms could, in principle, describe performance in our experiments and, specifically, the key finding that the overlapping stimuli were responded to differently in the context of a practiced sequence than in isolation. These algorithms are clearly not cognitive models, but still they may be useful in that they illustrate the algorithmic complexity of the obtained results. For example, imagine one needs to program the order of operations for a robot from 1 to n. This can be done in several ways, A–D.

In this (A) situation after 1, 2 has to appear. Even when a robot performs Action 2 after (say) 6 rather than after the Action 1, it knows to proceed to Action 3. In B, if 2 appears, then 3 may not necessarily appear, rather, only if 1 and 2 appear in sequence will 3 follow.

In C and D situations, Action 3 must appear after Action 2 that follows Action 1. In Situation C for example, when the robot performs Action 2 after (say) Action 6 rather than after the first action, it does not know that it has to continue to Action 3. If the robot in situation D performs Action 6 and then 3, it will correctly infer Action 4. Yet even in such a case the robot does not seem able to reproduce the obtained behavioral results, as the overlapping segment is performed differently in the original and novel routes. The very same route sequence is performed differently by the cognitive system according to the route context it appears in.

One of the possibilities that arise from this study is that during training, there is a transition from declarative memory of separate connections between the locations from 1 to n, that is as in A, to procedural and automatic execution where Action 1 leads to Action 2 which leads to Action 3 which leads to 4 as in B, C and D. If one preforms the route in an automatic manner as a unit, but at some point transfers to a different route that partly overlaps with the old route, performance must revert again to declarative memory of separate connections between the locations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hoffman, Y., Perlman, A., Orr-Urtreger, B. et al. Unitization of route knowledge. Psychological Research 81, 1241–1254 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-016-0811-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-016-0811-0