Abstract

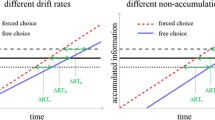

Choosing among different options is costly. Typically, response times are slower if participants can choose between several alternatives (free-choice) compared to when a stimulus determines a single correct response (forced-choice). This performance difference is commonly attributed to additional cognitive processing in free-choice tasks, which require time-consuming decisions between response options. Alternatively, the forced-choice advantage might result from facilitated perceptual processing, a prediction derived from the framework of implementation intentions. This hypothesis was tested in three experiments. Experiments 1 and 2 were PRP experiments and showed the expected underadditive interaction of the SOA manipulation and task type, pointing to a pre-central perceptual origin of the performance difference. Using the additive-factors logic, Experiment 3 further supported this view. We discuss the findings in the light of alternative accounts and offer potential mechanisms underlying performance differences in forced- and free-choice tasks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Note that Berlyne (1957a, b) has already speculated about why participants do respond at all in free-choice tasks and why the respective RTs are longer than in forced-choice tasks. Briefly, he alluded to the idea of enhanced response competition in the case of free-choice tasks where no clear stimulus-induced bias exists. We return to this interpretation in the General Discussion and relate it to the present findings.

Of course, individuals could spontaneously (i.e., without explicit instruction) conceive free choices as stimulus–response links like “if an X appears, then I press the left key about half of the times”. However, research indicates that most individuals substantially benefit from the explicit instruction to use such stimulus–response links (for review, see Gollwitzer & Sheeran, 2006), suggesting that spontaneous planning does not play a critical role. Further, implementation intentions are the more effective the more clearly defined the linked behavior in the “then”-part is (Gollwitzer, 1993; Gollwitzer, Wieber, Meyers, & McCrea, 2010). The definiteness of the if–then plan is necessarily higher for forced- than for free-choice tasks in setups like the present study. Thus, one might in fact speak of stimulus–response links that are provided by forced-choice instructions. We do not deny this possibility and return to this view in the General Discussion. For now, however, as our reasoning was derived from the framework of implementation intentions, we prefer speaking of if–then plans.

In Berlyne’s (1957a) experiments both (forced-choice) stimuli were presented in a free-choice trial.

Due to a programming error, participants 1–16 of Experiment 1b had only 85 instead of 90 trials per block.

At least in Experiment 3, Berlyne (1957a) doubled the free-choice trials for analyses to reach a comparable numbers of trials.

This refers not only to the immediately preceding trial, but to the longer history of previous responses.

References

Aarts, H., Dijksterhuis, A., & Midden, C. (1999). To plan or not to plan? Goal achievement or interrupting the performance of mundane behaviors. European Journal of Social Psychology, 29, 971–979.

Achtziger, A., Bayer, U. C., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (2012). Committing to implementation intentions: attention and memory effects for selected situational cues. Motivation and Emotion, 36, 287–300.

Bayer, U. C., Achtziger, A., Gollwitzer, P. M., & Moskowitz, G. B. (2009). Responding to subliminal cues: do if-then plans facilitate action preparation and initiation without conscious intent? Social Cognition, 27, 183–201.

Berlyne, D. E. (1957a). Conflict and choice time. British Journal of Psychology, 48, 106–118.

Berlyne, D. E. (1957b). Uncertainty and conflict: a point of contact between information-theory and behavior-theory concepts. Psychological Review, 64, 329–339.

Bieleke, M., Dambacher, M., Hübner, R., & Gollwitzer, P.M. (2013). A sequential sampling model account of implementation intention effects. Manuscript in preparation.

Brandstätter, V., Lengfelder, A., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (2011). Implementation intentions and efficient action initiation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81, 946–960.

Brass, M., & Haggard, P. (2008). The what, when, whether model of intentional action. The Neuroscientist, 14, 319–325.

Elsner, B., & Hommel, B. (2001). Effect anticipation and action control. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 27, 229–240.

Frith, C. (2013). The psychology of volition. Experimental Brain Research, 229, 289–299.

Gaschler, R., & Nattkemper, D. (2012). Instructed task demands and utilization of action effect anticipation. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 578.

Gollwitzer, P. M. (1993). Goal achievement: the role of intentions. European Review of Social Psychology, 4, 141–185.

Gollwitzer, P. M. (1999). Implementation intentions: strong effects of simple plans. American Psychologist, 54, 493–503.

Gollwitzer, P. M., & Brandstätter, V. (1997). Implementation intentions and effective goal pursuit. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 186.

Gollwitzer, P. M., & Sheeran, P. (2006). Implementation intentions and goal achievement: a meta-analysis of effects and processes. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 69–119.

Gollwitzer, P. M., Wieber, F., Meyers, A. L., & McCrea, S. M. (2010). How to maximize implementation intention effects. In C. R. Agnew, D. E. Carlston, W. G. Graziano, & J. R. Kelly (Eds.), Then a miracle occurs: focusing on behavior in social psychological theory and research (pp. 137–161). New York: Oxford Press.

Herwig, A., & Horstmann, G. (2011). Action–effect associations revealed by eye movements. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 18, 531–537.

Herwig, A., Prinz, W., & Waszak, F. (2007). Two modes of sensorimotor integration in intention-based and stimulus-based actions. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 60(11), 1540–1554.

Herwig, A., & Waszak, F. (2009). Intention and attention in ideomotor learning. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 62, 219–227.

Herwig, A., & Waszak, F. (2012). Action–effect bindings and ideomotor learning in intention- and stimulus-based actions. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 444.

Hommel, B. (1998). Automatic stimulus-response translation in dual-task performance. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 24, 1368–1384.

Hommel, B., Müsseler, J., Aschersleben, G., & Prinz, W. (2001). The theory of event coding (TEC): a framework for perception and action planning. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 24, 849–937.

Hübner, R., Steinhauser, M., & Lehle, C. (2010). A dual-stage two-phase model of selective attention. Psychological Review, 117(3), 759–784. doi:10.1037/a0019471.

Janczyk, M. (2013). Level 2 perspective taking entails two processes: evidence from PRP experiments. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 39, 1878–1887.

Janczyk, M., Heinemann, A., & Pfister, R. (2012a). Instant attraction: immediate action–effect bindings occur for both, stimulus- and goal-driven actions. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 446.

Janczyk, M., Nolden, S., & Jolicoeur, P. (2014). No difference in dual-task costs between forced- and free-choice tasks. Manuscript in revision.

Janczyk, M., Pfister, R., Crognale, M., & Kunde, W. (2012b). Effective rotations: action effects determine the interplay of mental and manual rotations. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 141, 489–501.

Janczyk, M., Skirde, S., Weigelt, M., & Kunde, W. (2009). Visual and tactile action effects determine bimanual coordination performance. Human Movement Science, 28, 437–449.

Kühn, S., Elsner, B., Prinz, W., & Brass, M. (2009). Busy doing nothing: evidence for nonaction–effect binding. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 16, 542–549.

Kunde, W. (2001). Response-effect compatibility in manual choice reaction tasks. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 27, 387–394.

Kunde, W., Pfister, R., & Janczyk, M. (2012). The locus of tool-transformation costs. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 38, 703–714.

Lengfelder, A., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (2001). Reflective and reflexive action control in patients with frontal brain lesions. Neuropsychology, 15, 80–100.

Lien, M.-C., & Proctor, R. W. (2002). Stimulus-response compatibility and psychological refractory period effects: implications for response selection. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 9, 212–238.

Mattler, U., & Palmer, S. (2012). Time course of free-choice priming effects explained by a simple accumulator model. Cognition, 123, 360–437.

Metzker, M., & Dreisbach, G. (2009). Bidirectional priming processes in the Simon task. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 35, 1770–1783.

Miller, J., & Reynolds, A. (2003). The locus of redundant-targets and non-targets effects: evidence from the psychological refractory period paradigm. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 29, 1126–1142.

Müsseler, J., & Hommel, B. (1997). Blindness to response-compatible stimuli. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 23, 861–872.

Nachev, P., Kennard, C., & Husain, M. (2008). Functional role of supplementary and pre-supplementary motor areas. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 9, 856–869.

Orbell, S., & Sheeran, P. (2000). Motivational and volitional processes in action initiation: a field study of the role of implementation intentions. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30, 780–797.

Paelecke, M., & Kunde, W. (2007). Action–effect codes in and before the central bottleneck: evidence from the psychological refractory period paradigm. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 33, 627–644.

Parks-Stamm, E. J., Gollwitzer, P. M., & Oettingen, G. (2007). Action control by implementation intentions: effective cue detection and efficient response initiation. Social Cognition, 25, 248–266.

Pashler, H. (1984). Processing stages in overlapping tasks: evidence for a central bottleneck. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 10, 358–377.

Pashler, H. (1994). Dual-task interference in simple tasks: data and theory. Psychological Bulletin, 116, 220–244.

Pashler, H., & Johnston, J. C. (1989). Chronometric evidence for central postponement in temporally overlapping tasks. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 41A, 19–45.

Passingham, R. E., Bengtsson, S. L., & Lau, H. C. (2010). Medial frontal cortex: from self-generated action to reflection on one’s own performance. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 14, 16–21.

Pfister, R., Heinemann, A., Kiesel, A., Thomaschke, R., & Janczyk, M. (2012). Do endogenous and exogenous action control compete for perception? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 38, 279–284.

Pfister, R., Kiesel, A., & Hoffmann, J. (2011). Learning at any rate: action–effect learning for stimulus-based actions. Psychological Research, 75, 61–65.

Pfister, R., Kiesel, A., & Melcher, T. (2010). Adaptive control of ideomotor effect anticipations. Acta Psychologica, 135(3), 316–322.

Pfister, R., & Kunde, W. (2013). Dissecting the response in response-effect compatibility. Experimental Brain Research, 224, 647–655.

Posner, M. I. (1980). Orienting of attention. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 32, 3–25.

Posner, M. I., Snyder, C. R., & Davidson, B. J. (1980). Attention and the detection of signals. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 109, 160–174.

Prinz, W. (1998). Die Reaktion als Willenshandlung. Psychologische Rundschau, 49, 10–20.

Ratcliff, R. (1978). A theory of memory retrieval. Psychological Review, 85(2), 59–108.

Schüür, F., & Haggard, P. (2011). What are self-generated actions? Consciousness and Cognition, 20, 1697–1704.

Schweickert, R. (1978). A critical path generalization of the additive factor method: analysis of a Stroop task. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 18, 105–139.

Sternberg, S. (1969). The discovery of processing stages: extensions of Donders’ method. Acta Psychologica, 30, 276–315.

Telford, C. W. (1931). The refractory phase of voluntary and associative responses. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 14, 1–36.

Tombu, M., & Jolicoeur, P. (2003). A central capacity sharing model of dual-task performance. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 29, 3–18.

Van Selst, M., & Jolicoeur, P. (1997). Decision and response in dual-task interference. Cognitive Psychology, 33, 266–307.

Webb, T. L., & Sheeran, P. (2007). How do implementation intentions promote goal attainment? A test of component processes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43, 295–302.

Welford, A. T. (1951). The “psychological refractory period” and the timing of high-speed performance: a review and a theory. British Journal of Psychology, 43, 2–19.

Wieber, F., & Sassenberg, K. (2006). I can’t take my eyes off it: attention attraction effects of implementation intentions. Social Cognition, 24, 723–752.

Wolfensteller, U., & Ruge, H. (2011). On the timescale of stimulus-based action–effect learning. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 64, 1273–1289.

Wykowska, A., & Schubö, A. (2012). Action intentions modulate allocation of visual attention: electrophysiological evidence. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 379.

Wykowska, A., Schubö, A., & Hommel, B. (2009). How you move is what you see: action planning biases selection in visual search. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 35, 1755–1769.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG; German Research Foundation), grant JA 2307/1-1 awarded to Markus Janczyk. The co-authors were supported by the DFG research unit FOR 1882 Psychoeconomics. We thank Arvid Herwig for many helpful comments on a previous version of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Janczyk, M., Dambacher, M., Bieleke, M. et al. The benefit of no choice: goal-directed plans enhance perceptual processing. Psychological Research 79, 206–220 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-014-0549-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-014-0549-5