Abstract

Nemrut volcano, adjacent to Lake Van (Turkey), is one of the most important peralkaline silicic centres in the world, where magmatism for ~570,000 years has been dominated by peralkaline trachytes and rhyolites. Using onshore and Lake Van drill site tephra samples, we document the phenocryst and glass matrix compositions, confirming a complete spectrum from very rare mafic to dominantly silicic magmas. Magma mixing has been common and, along with the multi-lineage nature of the magmas, indicates that Nemrut has been a very open system where, nevertheless, compositionally zoned caps developed during periods of relative eruptive quiescence. Geothermometry suggests that the intermediate-silicic magmas evolved in an upper crustal magma reservoir at temperatures between 1100 and 750 °C, at fO2 close to the FMQ buffer. The silicic magmas either were halogen poor or exsolved a halogen-rich phase prior to or during eruption. An unusual Pb-rich phase, with up to 98.78 wt% PbO, is interpreted as having exsolved from the intermediate-rhyolitic magmas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The majority of igneous suites containing peralkaline silicic members are essentially basalt-driven systems, in the sense that basalt has been the parental magma from which more evolved rocks have been derived, or has provided the heat source for partial melting of various crustal rocks (Mahood and Baker 1986; Bohrson and Reid 1997; Macdonald 2012). Considerable research effort has been focussed, therefore, on the primary role of basalt and has tried to evaluate the various factors that lead to peralkaline silicic end points, particularly the polybaric fractionation histories. Approaches can be broadly divided into three types. In one-stage models, the peralkaline melts are formed dominantly by fractional crystallisation of basaltic parental magmas (Barberi et al. 1975; Civetta et al. 1998; Peccerillo et al. 2003; Macdonald et al. 2008a, b; White et al. 2009; Neave et al. 2012; Rooney et al. 2012). Two-stage models for the origin of peralkaline silicic rocks usually involve partial melting of (underplated?) basalts to form peralkaline trachyte, followed by fractional crystallisation of the trachyte to form peralkaline rhyolites (Lowenstern and Mahood 1991; Bohrson and Reid 1997; Trua et al. 1999; Avanzinelli et al. 2004). In the third type of model, the formation of the peralkaline melts is by partial melting of continental crust; basalt does not directly contribute to melt production but may be the heat source promoting the melting (Bailey and Macdonald 1970; Macdonald et al. 1987; White et al. 2006). Other processes, such as magma mixing and crustal contamination, may be involved in all three types of petrogenesis. In this paper, we explore various aspects of the origin and evolution of peralkaline eruptive rocks at the Nemrut caldera volcano, Turkey.

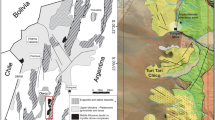

Nemrut is the most active centre in Turkey. It has been the source of intense Plinian eruptions for >570,000 years, as documented by Sumita and Schmincke (2013a, b, c) and Schmincke et al. (2014) in stratigraphic traverses over an area of >6000 km2 mainly to the west of Lake Van and in drill cores of the 2010 ICDP Paleovan project (Fig. 1) (Litt et al. 2011). Magmatism has been dominated by metaluminous to peralkaline trachytes and rhyolites, and the possibility of placing compositional variability in the magmas into a tightly controlled stratigraphic framework gives the centre a special significance in the study of peralkaline felsic systems. Furthermore, Nemrut tephras are important in paleoclimate and archaeological research in lake studies not only in Turkey but in adjacent countries such as Armenia, Azerbaijan and Iran (Sumita and Schmincke 2013c).

a Overview map of Turkey, Anatolian, Eurasian and Arabian plates, with Lake Van just north of the collision zone. NAF North Anatolian Fault, EAF East Anatolian Fault. b Map of Lake Van and its surroundings, notably the Nemrut and Süphan volcanoes. The Northern Basin (NB) and Ahlat Ridge (AR) coring stations are shown. Locality numbers correspond to the sampling localities of onshore samples. Map modified from Sumita and Schmincke (2013c)

Çubukçu et al. (2012) provided an extensive mineral-chemical and whole-rock geochemical database, and some age determinations, for Nemrut lavas and domes, using samples often difficult to place in a stratigraphic framework. Sumita and Schmincke (2013a, b, c) studied the stratigraphy, temporal evolution and whole-rock, matrix glass and phenocryst compositions of the volumetrically dominant onshore pyroclastic deposits of Nemrut over 400 ka. Schmincke et al. (2014) studied in more detail the mineralogy, glass compositions and volcanology of the Alleroed and Holocene drilled tephras from both Nemrut and the adjacent subalkaline Süphan volcano. We have selected a suite of tephra samples covering the compositional spectrum from mugearite to peralkaline rhyolite, with which to study in greater depth mineral-chemical and melt (glass) compositional trends and to assess their significance for the evolution of the Nemrut magmatic system. Specifically, we (1) provide a complete series of melt compositions between mugearite and peralkaline rhyolite and comment on their significance for the existence of the Daly gap; (2) describe the P–T–fO2 conditions operative in the magma reservoir; (3) assess the significance of alkali feldspar–glass relationships for the evolution of peralkaline silicic magmas; and (4) provide preliminary information on an unusual Pb-rich phase which may have exsolved from the Nemrut magmas.

Geological setting

Nemrut volcano is situated on the East Anatolian plateau, which is generally considered to have formed by the collision of the Arabian Peninsula with the Eurasian plate, leading to the uplift of an area exceeding 20,000 km2 (Fig. 1). The close relationships between tectonic and volcanic events in the region have been discussed by Pearce et al. (1990), Şenğor et al. (2003) and Keskin (2003, 2007). Voluminous magma generation is thought to have been promoted by slab steepening and break-off in the Middle Miocene, suggesting that the mantle lithosphere is either very thin or absent beneath a considerable part of the area.

As a result of collision, the North Anatolian Block, bordered to the north by the right-lateral strike-slip North Anatolian Fault and to the south by the left-lateral East Anatolian Fault (Fig. 1), moved westwards, with the Muş and adjacent Van basins being formed as pull-apart basins. Since before 0.5 Ma, Nemrut volcano has been growing in the hinge zone between the two basins and may have been responsible for damming the huge Lake Van in the Van tectonic basin (Sumita and Schmincke 2013a). Çubukçu et al. (2012) speculated that the peralkaline magmatism at Nemrut was related to the ascent of asthenospheric partial melts into upper crustal levels under the Muş basin, where pre-existing shear zones gained a strike-slip component leading to localised extension.

Volcanological framework

Although explosive activity at Nemrut may have started prior to ~600 ka, the oldest onshore deposits so far found, south of Lake Van, have recently been dated as ~570 ka (Sumita and Schmincke 2013a and unpublished data). These authors have distinguished about forty widespread trachytic and rhyolitic fallout tephras and about twelve interbedded ignimbrites and have subdivided the succession into three age groups, bound by widespread, distinctive tephra units. Group 1 (~405–200 ka) comprises some widespread fallout tephras and several ignimbrites. The deposits of Group 2 were emplaced between ~190 and 30 ka. The older date (~190 ka) is for AP-1, a huge rhyolitic Plinian fallout deposit overlain by a cogenetic ignimbrite with a combined magma volume (DRE; dense rock equivalent) of ~30 km3. The tephra section drilled at Lake Van also shows a major increase in Nemrut tephras starting at ~200 ka, suggesting that the increase in explosive volcanism of Nemrut at ~200 ka is real. Group 3 begins with the compositionally zoned Nemrut Formation (NF; 30 ka) which consists of several members in a complex sequence of fallout-surge-ignimbrite-surge-fallout deposits. A prominent agglutinate and underlying trachytic fallout north of Tatvan, formerly correlated with NF (Sumita and Schmincke 2013c), is now correlated by us with the ~60 ka trachytic AP-6 (HP-10). The tephras of the Çekmece Formation, previously thought by Sumita and Schmincke (2013c) to overlie NF are now thought to be older than NF. Details of the correlation are, however, still under study (see Fig. 2).

Stratigraphic position of the analysed samples is shown for onshore samples in (a); modified from Sumita and Schmincke (2013c). The stratigraphic column (Site 2) for core samples (b) is taken from Stockhecke et al. (2014). Sample V-16 is from an older piston core site (see Schmincke et al. 2014). Ages for onshore samples were presented in Sumita and Schmincke (2013a). Ages for core samples are still approximate and will be presented in detail by Sumita and Schmincke (in prep.)

Three points made by Sumita and Schmincke (2013a, c) are relevant to the evolution of the Nemrut system. First, starting with AP-1 at ~190 ka, major eruptions appear to have occurred at intervals spaced some 20–40,000 years apart, which were interpreted as being the incubation times for the silicic magmas to develop into eruptible volumes. Second, peralkalinity peaked at ~120 ka with the strongly peralkaline AP-4 but has decreased since. Third, the number and frequency of large volume, mostly rhyolitic fall deposits, seem to have increased since ~300 ka, particularly with the large-volume AP-1 at ~190 ka. The increase in tephra output has remained high until the present.

In the spectrum of silicic caldera systems (Smith 1979), Nemrut is small- to medium-sized, as is typical of peralkaline volcanoes (Mahood 1984; Macdonald 2012). The rhyolitic eruption rates (at intervals of ~20–40 ky) are similar to other long-lived peralkaline volcanoes, such as Gran Canaria (Schmincke and Sumita 1998), whilst erupted tephra volumes are smaller. Among peralkaline centres, Baitoushan Volcano, situated in a continental rift setting straddling the North Korea–China border, is a close compositional analogue to Nemrut (Horn and Schmincke 2000). Baitoushan is a composite cone built largely of trachytic and comenditic lava flows, fallout and ignimbrites.

Samples and analytical methods

We have analysed in detail six tephra samples from onshore and six from the 219-m ICDP Lake Van drill core from Site 2, selected to cover the compositional range mugearite to peralkaline rhyolite (Figs. 1, 2). For further analyses of the main phenocryst phases from additional onshore and drilled tephra units, see Sumita and Schmincke (2013c) and Schmincke et al. (2014). Table 1 lists the sample numbers, their origin and their approximate age. The samples range in age from 2.6 to ~530 ka, covering much of the eruptive history of the volcano.

Mineral compositions were determined by electron microprobe at the Inter-Institute Analytical Complex at the Institute of Geochemistry, Mineralogy and Petrology, University of Warsaw, using a Cameca SX-100 microprobe equipped with three wavelength dispersive spectrometers. As an example of the analytical conditions, those for chevkinite-(Ce) were accelerating voltage 15 kV and the probe current 40 nA, with counting times of 20 s on peak and 10 s on each of two background positions. The standards, crystals and X-ray lines used and generalised detection limits are given in the Appendix. The “PAP”φ(ρZ) program (Pouchou and Pichoir 1991) was used for corrections. Analytical conditions for other minerals may be obtained from the authors. Apatite was analysed using the technique outlined in Macdonald et al. (2008a). Estimates of analytical precision (1σ; wt%) for all phases except glass are: Si 0.07, Ti 0.03, Al 0.02, Cr 0.02, Ni 0.03, Fe 0.09, Mn 0.03, Mg 0.04, Ca 0.08, Na 0.01, K 0.01. For glass analyses, the values are Si 0.40, Ti 0.03, Al 0.14, Fe 0.29, Mn 0.12, Mg 0.02, Ca 0.03, Na 0.17, K 0.11, P 0.03, Cl 0.03, F 0.08. Averages and/or representative analyses are presented in Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8; the full data set is given in Tables 1–4 in ESM.

Petrography

The rock nomenclature used here is based on the matrix glass composition; we acknowledge that the glass composition in porphyritic samples will normally be more evolved than the whole-rock composition. The primary classification is from Le Bas et al. (1986) and the peralkaline trachytes and rhyolites are classified using the Macdonald (1974) scheme.

In detail, the Nemrut rocks are very complex. For example, whole rocks and matrix glasses described by Sumita and Schmincke (2013a, b, c) as broadly trachytic comprise silica-saturated and silica-undersaturated, and metaluminous and peralkaline varieties. Certain trachytic units were distinguished on the basis of trace element characteristics, such as high Ba and Sr. In the peralkaline rhyolites, Sumita and Schmincke (2013c) recognised three distinct assemblages including aenigmatite in addition to alkali feldspar and FeTi oxides; aenigmatite + quartz, aenigmatite + Fe-rich clinopyroxene + quartz and aenigmatite + hedenbergite + fayalitic olivine. A fourth assemblage, aenigmatite + hedenbergite + fayalitic olivine + quartz, is added below (sample 2009-07-19-06). These must represent different magmatic evolutionary paths. It would be valuable to relate phenocryst assemblages to published whole-rock or glass compositions, but few analyses have so far been tied to specific mineral assemblages, especially for cored tephra samples whose volume is generally too small to allow bulk rock analyses of pumice clasts. The following discussion relates mainly, therefore, to our study samples. Mineral assemblages are given in Table 1. Textural details of analysed samples are given in the Tables in ESM.

The primary phenocryst assemblage in the mugearites and benmoreites is olivine (ol) + clinopyroxene (cpx) + plagioclase (plag) + ilmenite (ilm) + magnetite (mt) ± apatite (ap). Judging from the compositions of xenocrysts in some mixed magma rocks (below), benmoreites mixed frequently with more felsic magmas. The metaluminous and peralkaline trachytes contain ol + cpx + ilm + mt + alkali feldspar (af) + ap. As noted above, the rhyolites show several phenocryst assemblages; a generalised assemblage is ol + cpx + af + ilm + mt + ap + quartz, joined, with increasing host-rock peralkalinity, by aenigmatite. Chevkinite-(Ce), zircon and pyrrhotite microphenocrysts are present in some rocks (Table 1). Mixed magma rocks can be recognised by containing matrix glasses of variable composition (e.g. 2009-07-19-06; Table 1) and/or more than one phenocryst population, e.g. the clinopyroxenes and feldspars in sample 2009-07-14-06.

Olivine phenocrysts occur mainly as discrete, subhedral, slightly resorbed crystals up to 600 μm across, some with inclusions of FeTi oxides, zircon, apatite and chevkinite (Fig. 3a). Two types of clinopyroxene are distinguishable optically: a pale brown to colourless type in the benmoreites and some trachytes, and a deep green variety in the more felsic rocks. In both, it occurs as euhedral to subhedral prisms, up to 1300 μm long, and as partly resorbed anhedral plates. The pyroxene may be included in olivine and plagioclase and itself commonly includes olivine, FeTi oxides, apatite and glass (melt) inclusions (Fig. 3b). Plagioclase phenocrysts in benmoreite sample 2009-07-16-05 form anhedral plates up to 450 μm across. In mixed magma rocks, they tend to be smaller, occurring, for example, as tiny (few tens of μm) laths in dark glass in sample V-279 (2G-28A-1, 26–32 cm). The dominant form of alkali feldspar phenocrysts occurs as euhedral to subhedral, partially resorbed plates up to 1250 μm across. Prismatic forms are less common. Rounded quartz phenocrysts occur in five samples, sometimes intergrown with alkali feldspar (Fig. 3c).

BSE images of mineralogical assemblages in the trachytes and rhyolites. a Sample 2008-07-07-03. Olivine (Ol) phenocryst includes, or is associated with, microphenocrysts of chevkinite (Chv), apatite (Ap) and zircon (Zrn) and melt (glass) inclusions (MI). b Sample 2008-07-07-03. Glass-rimmed clinopyroxene phenocryst has inclusions of ilmenite, chevkinite-(Ce), apatite and zircon. The largest ilmenite crystal contains four small zircons (≤10 m) not easily distinguishable on this image. c Sample 2007-07-05-13. Intergrowth of quartz (Qtz) and alkali feldspar (Kfs), rimmed by glass (Gl). d Sample V-89 (2B-8H-4 cc). Oscillatory zoned apatite in clinopyroxene (Cpx) phenocryst. The brighter zones reflect higher REE contents

Ilmenite occurs mainly as euhedral to subhedral crystals, up to 150 μm across, associated with, or included in, olivine and clinopyroxene phenocrysts (Fig. 3b). Titanomagnetite, up to 500 μm across, is included in olivine and clinopyroxene phenocrysts but also in feldspar phenocrysts and as discrete crystals. Ilmenite and titanomagnetite are occasionally found enclosed in the same crystal. Aenigmatite occurs as subhedral plates and prisms, up to 700 μm long.

Apatite microphenocrysts are mainly included in, or associated with, clinopyroxene phenocrysts (Fig. 3b), but also form inclusions in olivine (Fig. 3a), oxides and aenigmatite and, more rarely, discrete crystals in glass. They vary from euhedral prisms, exceptionally 250 μm long, to rounded forms up to 70 μm across. Zoning is best developed in the peralkaline rocks and includes both oscillatory and patchy types (Fig. 3d). Most commonly, bright (higher Z on BSE images) cores are rimmed by darker margins. Zircon occurs as anhedral crystals, up to 50 μm across, included in olivine (Fig. 3a) and clinopyroxene (Fig. 3b) phenocrysts. Chevkinite-(Ce) has been positively identified in sample 2008-07-03-03, where it occurs as rounded crystals (<50 μm) associated with zircon in clinopyroxene (Fig. 3a) and as a prism (93 μm long) attached to, and included in, olivine (Fig. 3a). We have also analysed chevkinite in an additional sample, V-16 (VAN04-2-4-S4, 83.5–84 cm; see Table 3 in ESM; core sample from 2004 expedition—details are in Schmincke et al. 2014), where it forms small anhedral plates and subhedral prisms. Rounded FeS inclusions are present in several rocks, most commonly as inclusions in clinopyroxene phenocrysts (Table 1), where analysed (sample 2009-07-19-06) the phase is pyrrhotite.

At least five samples contain unusual Pb-rich phases (Table 1), which, although superficially resembling amygdales, we interpret as having exsolved from magma. In comendite 2B-5H-5cc, the phase forms rounded to ellipsoidal “patches”, which, from the way in which they coalesce, were clearly deformable during melt movement. They did not grow in vesicles but rather resemble globules formed by liquid immiscibility (Fig. 4a). Perhaps the clearest evidence of the magmatic nature of at least some of the patches is shown in a feldspar crystal. In peralkaline rhyolite sample 2009-07-14-06 (Fig. 4b), a plagioclase xenocryst is complexly zoned from labradorite in the core (An69–61) through andesine (An50–48) to oligoclase (An29), with a return to labradorite (An60–52) at the rim. When the feldspar had reached andesine composition, there was precipitation of olivine (Fo60), clinopyroxene (Mg# ~56, where Mg# is magnesium number (Mg/(Mg + Fe2+)), titanomagnetite and a Pb-bearing phase, now found as abundant, variably sized inclusions trapped in the feldspar. This was followed by mixing of the benmoreitic/trachytic magma with more mafic magma, as indicated by the labradoritic rim, with no further release of the Pb-rich phase, which is absent from the rim.

BSE images of Pb-rich globules. a Comendite 2009-07-14-6. Globules stretched during late magma flowage, parallel to the vesicles. The variations in brightness in the globules reflect Si abundances (higher Z = lower Si). Pb1 is essentially Si-free; globules of type Pb2 have SiO2 values up to 33 wt%, which are thought to represent contamination of the analysis by the host. Note the coalescing nature of the globules, similar to immiscible droplets in igneous rocks. Note also that they generally do not occur in the vesicles, although they may overlap with them. The host glass is pristine, i.e. not devitrified. b Plagioclase xenocryst in sample 2009-07-14-6 contains inclusions of olivine, clinopyroxene, titanomagnetite and a Pb-rich phase (Pb)

Phenocryst compositions

Olivine

Compositions range from Fo59.2–0.4 (Table 1a in ESM), the Fo content decreasing with increasing host-rock SiO2 content and peralkalinity, as follows: mugearite Fo 57.7–41.7, trachyte 14.7–13.5, rhyolites 2.3–0.4. Two populations are present in 2007-07-19-06, Fo ~13.6 and ~5.0. Sample 2008-07-05-13 contains both trachytic and rhyolitic glasses; the analysed olivines are associated with the trachyte. MnO contents are up to 3.72 wt% (Tp 5.3), increasing with increasing Fa content. Levels of CaO are up to 0.61 wt%, and there is no correlation with Fo content.

Clinopyroxene

The full compositional range is from Ca45.8Mg48.5Fe5.7 to Ca42.7Mg0.5Fe56.8 (Table 2; Table 1b in ESM) (Fig. 5). The most magnesian compositions are found in the benmoreites, often as crystal cores, and in mixed magma rocks. Pyroxenes in trachytes and rhyolites are hedenbergite, with low Na contents (<0.2 apfu). Zoning is most pronounced in the benmoreites and metaluminous trachytes; one crystal in 2009-07-16-05 is zoned from Mg28.4–38.9, for example. In the salic rocks, zoning is usually ≤En2. Aluminium and Ti contents are low (≤0.131 and ≤0.042 apfu, respectively) and decrease with decreasing En content. In the benmoreites and some trachytes, the pyroxenes have Na < Al and pyroxene crystallisation would tend to increase the peralkalinity of residual melts. In other trachytes and the rhyolites, Na exceeds Al and pyroxene crystallisation alone would tend to decrease the peralkalinity of residual melts, the so-called clinopyroxene effect of Scaillet and Macdonald (2003).

Composition of Nemrut clinopyroxene phenocrysts plotted in the Di–Hd–En–Fs quadrilateral. Onshore (a) and core (b) samples are shown separately. The two diopside-rich analyses are exceptional for Nemrut and may represent reworked material from Süphan (Schmincke et al. 2014)

Orthopyroxene

Orthopyroxene (Wo2.9En54.5Fs42.6) forms the core to a rounded grain (160 × 120 μm) rimmed by clinopyroxene (Wo4.5En37.2Fs21.3) in sample 2009-07-19-06 (Table 1b in ESM). The orthopyroxene may be a xenocryst from wall rocks. However, there is some evidence that the phase may crystallize in alkaline suites. Freundt-Malecha et al. (2001) reported rare orthopyroxene (En75–70) in cognate syenogabbro fragments in the Miocene rhyolitic–basaltic composite ignimbrite P1 on Gran Canaria, and orthopyroxene is also a common, although minor, phase in the basal ignimbrites of the Miocene peralkaline ignimbrite succession on Gran Canaria (Schmincke and Sumita 1998). In a series of experiments on a hawaiite, Nekvasil et al. (2004) found orthopyroxene (En65–58) crystallizing in equilibrium with kaersutite at 9.3 kbar, T = 1040–1000 °C, at “high” water contents. Rooney et al. (2012) found, during MELTS modelling, that the transition trachyte to rhyolite in the 3.1 Ma peralkaline Chefe Donsa phreatomagmatic deposits on the shoulder of the Main Ethiopian Rift required minor amounts of orthopyroxene in the crystallizing assemblage, although the phase was not recorded modally. The possibility cannot be precluded that (some) Nemrut magmas passed through an orthopyroxene stability field at high pressure, the mineral very rarely surviving resorption at lower pressures.

A further option is that the orthopyroxene is a relict of mixing between a Nemrut magma and magma from the neighbouring Süphan volcano. Süphan rocks are commonly orthopyroxene-phyric, and Sumita and Schmincke (2013c) have speculated that magmas from the volcano may have entered the Nemrut system at various stages, e.g. following the huge eruption of the Nemrut Formation fallout and pyroclastic flow. Analyses of orthopyroxene in Süphan tephras are given in Schmincke et al. (2014).

Feldspar

Feldspar compositions range from An69.0Ab29.9Or1.1 to An0.0Ab57.6Or42.4, i.e. labradorite to sanidine (Fig. 6; Table 1c in ESM). It is likely that the most calcic phases (An > 50), which are restricted to mixed magma rocks, crystallized from basaltic magmas. ivAl is low (<0.1 apfu) in the alkali feldspars but up to 0.692 apfu in plagioclase, with ivAl/viAl ratios as high as 0.71. Iron contents (≤1.16 wt% Fe2O3) are within the range normally recorded in peralkaline salic rocks (≤1.5 wt%; Macdonald et al. 2011). The alkali feldspar host rocks evolve to around Or41 in the most peralkaline rhyolites, in line with experimental evidence from peralkaline rhyolites from the Kenya Rift which showed that at melt proportions <60 wt% the alkali feldspar composition remained constant at ~Or40 (Scaillet and Macdonald 2003, 2006). It is also consistent with data from the peralkaline rhyolites of Pantelleria, Italy, where the alkali feldspars evolve to a composition of Or39 (Neave et al. 2012).

FeTi oxides

Ilmenite compositions fall in the range X ilm 92–99, values generally increasing with increasing melt peralkalinity and SiO2 content (Table 2c in ESM). Manganese contents are low (0.011–0.037 apfu; 0.52–1.89 wt% MnO). Contents of Mg range from 0. to 0.155 apfu (b.d.–4.24 wt% MgO) and decrease with increasing X ilm. Niobium varies from 0 to 0.007 apfu (<0.08–0.52 wt% Nb2O5) and also decreases with increasing X ilm. Spinel compositions are in the range X usp 61–73, the highest values tending to be in the peralkaline rhyolites. Levels of Al2O3 are up to 1.3 wt%, with the exception of a partly resorbed, zoned crystal in 2009-07-16-05, with core and rim values of 3.24 and 3.19 wt%, respectively. Unlike the other spinels, this crystal has detectable V2O3 contents (0.95, 1.07 wt%) and the highest MgO values in the data set (3.77, 3.67 wt%), consistent with the intermediate composition of the host.

Aenigmatite

Macdonald et al. (2011) noted that, although Ti and Fe variations are limited in aenigmatite phenocrysts from peralkaline rhyolites, there are significant ranges in Al2O3 and CaO contents, such that compositional variation can be expressed by the coupled substitution IVSi + VIIINa ↔ IVAl + VIIICa (Kunzmann 1999) (Fig. 7). The Nemrut data extend the field of aenigmatite phenocryst compositions in peralkaline rhyolites to slightly lower Na and Si contents (Table 3; Table 2b in ESM). There is observational (Macdonald et al. 2011) and experimental (Di Carlo et al. 2010) evidence that phenocrystic aenigmatite is restricted to rhyolites with peralkalinity index >1.2. This is consistent with its occurrence in the Nemrut samples, where the aenigmatite-phyric glasses are transitional from comendite to pantellerite (see below).

(Ca2+ + Al3+) plotted against (Na+ + Si4+) to demonstrate substitution among the minor components in Nemrut aenigmatite phenocrysts. The field encloses data for peralkaline rhyolites from Pantelleria (Italy), Mayor Island (New Zealand), Gedemsa (Ethiopia), Eburru and Olkaria (Kenya) and Socorro (Mexico), from compilation by Macdonald et al. (2011). The Nemrut data extend the field to more (Ca + Al)-rich compositions, consistent with their relatively low peralkalinity indices. Data from Table 2b in ESM

Apatite

Both hydroxylapatite and fluorapatite are present (Table 4; Table 2c in ESM), but there is no relationship between apatite and whole-rock compositions. The main compositional variation can be expressed as REE3+ + Si4+ = Ca2+ + P5+ (Fig. 8). The britholite component, as inferred by the sum of REE + Si apfu, increases in the sequence mugearite–trachyte–rhyolite, to a maximum value of 0.8 (~10 %). An increasing britholite component is positively correlated with Na, [Ce/Y]CN and broadly with Fe.

The low britholite component in the Nemrut apatites is consistent with data for other peralkaline silicic suites. Mahood and Stimac (1990) found REE + Si values ≤0.5 apfu in Pantellerian trachytes and pantellerites, and Macdonald et al. (2011) recorded up to ~7 mol% solid solution towards britholite-(Ce) in apatites from pantelleritic trachytes of the Menengai volcano, Kenya. In contrast, Macdonald et al. (2008a) found up to 35 % britholite component in apatite in comendites of the Olkaria complex, Kenya. The reasons why apatites from more strongly peralkaline (pantelleritic) rocks are less REE-enriched than those from mildly peralkaline (comenditic) rocks are not known.

Compositional zoning in apatite, as in other accessory phases, can result from magma mixing, changes in crystal/melt partitioning and kinetic effects (Tepper and Kuehner 1999; Boyce and Hervig 2009). The observation that complex zoning at Nemrut occurs in apatites in unzoned host minerals (Fig. 3d), which judging from melt–crystal systematics are in, or close to, equilibrium, makes it likely that the zonation is a result of kinetic factors controlling element migration into the growing crystals. Furthermore, the strongest zonation occurs in those with the highest britholite (REE + Si) component. We can thus speculate that the diffusion rates of REE were lower than crystal growth rates (Watson et al. 1985), resulting in build-up of REE at crystal faces, followed by rapid crystallisation, leading cyclically to element depletion. The diffusion rate may have been slower than that of REE alone because of the movement of Si as the charge-balancing element, e.g. REE3+ + Si4+ = Ca2+ + P5+ (Cherniak 2000).

Chevkinite-(Ce)

The REE–Fe–Ti silicate chevkinite has the general formula A4BC2D2(Si2O7)2O8, where the dominant cations in each site are: A = Ca, REE (and Y); B = Fe2+; C = Fe2+, Fe3+, Ti; and D = Ti. Six EMP analyses of chevkinite crystals included in clinopyroxene, or attached to olivine, phenocrysts in comendite sample 2008-07-03-03, and six analyses of grains variably associated with clinopyroxene and feldspar phenocrysts in sample VAN04-2-4-S4, are presented in Table 3a in ESM. Cation sums are in the range 13.03–13.20 (average 13.10), fairly close to the ideal value of 13. The formula can be given as (Ce1.67La0.95 Ca0.61Nd0.55Pr0.17Y0.08)4.03 Fe2+(Fe 2+0.95 Ti0.81Nb0.07Zr0.04Mn0.04)1.91(Si1.99O7)1.98O8. The dominance of Ce in the A site makes the phase chevkinite-(Ce). Fe2+ is dominant in the C site, and Th, Nb and Zr contents are all rather low (<0.09 apfu). There are slight differences in the minerals in the two samples; chevkinite-(Ce) in 2008-07-03-03 has slightly higher Nb, Th, Sm, Y and Al contents, and lower Ti, La, Ce and Nd contents than that in V-16 (VAN04-2-4-S4, 83.5–84 cm).

The Nemrut chevkinite-(Ce) is compositionally similar to chevkinite reported from other peralkaline rhyolites, e.g. the Kane Wash Tuff, Nevada (Novak and Mahood 1986), the Olkaria complex, Kenya (Macdonald et al. 2002, 2008b) and Gran Canaria (Troll et al. 2003).

Zircon

Four analyses of zircon are given in Table 3b in ESM. They are close to stoichiometric (Zr1.00Si0.99O4), with Fe, Ti, P, Hf and Y in trace amounts (all ≤0.01 apfu).

Pyrrhotite

Pyrrhotite in sample 2009-07-19-06 forms inclusions in olivine phenocrysts. The formula is Fe0.93S1.00, with trace amounts of Co, Cu, Pb and Zn (<0.01 apfu).

Pb-bearing phase(s)

The globules proved difficult to analyse by microprobe. They are composed of aggregates of crystals whose size is below resolution of standard SEM and the surfaces are not flat. The phases were also very unstable during analysis. Point analyses are often, therefore, a composite of the Pb-bearing phase and the host material, which appear as components with higher and lower Z on BSE images (Fig. 4a). Table 5 presents electron microprobe analyses of eight globules. The components are presented as oxides, although we have no good evidence as to the real chemical species. There are two “end-member” compositions. In one, PbO is overwhelmingly the dominant component, up to 98.78 wt% (Table 5; Table 3c in ESM). In the other, PbO abundances are lower (~80 wt%) and the analytical totals are also lower (81–82 wt%). Despite careful search, neither S nor F was detected in any globule. Furthermore, EDS spectra indicated the presence of a significant C peak, several times higher than the peak from the carbon coating of the thin section. It appears that the second phase is a carbonate.

The presence of PbO and PbCO3 components was confirmed by Raman spectroscopy, conducted in the Department of Chemistry, University of Warsaw, using a Labram HR800 (Horiba Jobin-Yvon) spectrometer. Peaks at 141.5 and 1050 cm−1 indicated PbO and PbCO3, respectively. Details of the methodology used are given in the Appendix. We know of no published report of PbO or PbCO3 phases occurring apparently as magmatic phases and currently have no explanation of the origin of the globules. Further work is in progress.

Matrix glass and melt inclusion compositions

First, any compositional modifications due to secondary hydration, to which pyroclastic peralkaline rocks are particularly prone, must be assessed. Oxide totals range from 95.06 to 101.87 wt%, with an average of 98.86 wt%, indicating generally low water contents, in agreement with many glass analyses of Nemrut tephra presented by Sumita and Schmincke (2013c) and Schmincke et al. (2014). Thus, although some samples may have been mildly hydrated, it appears that the majority represent pre-eruptive compositions, with the exception of volatiles probably degassed prior to, and during, eruption.

Matrix glass compositions range from mugearite and benmoreite through metaluminous trachyte to peralkaline trachyte and rhyolite (Table 6; Table 4a in ESM). Melt inclusions from olivine and pyroxene phenocrysts cover a similar compositional range to the matrix glasses and in the following are discussed together with the matrix glasses. With increasing SiO2 contents, MgO, CaO, TiO2 and FeO* contents decrease (Fig. 9). Al2O3 peaks at ~60 wt% SiO2. A notable feature is the large range in FeO* contents (1.5–4.5 wt%) at a given SiO2 content in the rhyolites. This is discussed below. The contents of both Na2O and K2O increase to ~65 wt% SiO2 and then decrease. This behaviour is rather unusual for peralkaline suites, where Na generally increases with increasing differentiation whilst K remains about constant. The trends are broadly similar to those found by Çubukçu et al. (2012) in their study of Nemrut and to those for the compositionally zoned Nemrut Formation, which varies from lower comenditic fallout through middle trachytic ignimbrite to mugearitic fallout (Sumita and Schmincke 2013c). One group of analyses in the new data set, all from sample 2009-07-16-05, is unusual in having high Na2O (4.8–5.4 wt%) for its SiO2 contents (51–64 wt%). It is uncertain whether the analyses represent a slightly different, higher Na, magmatic lineage or are a result of local alkali mobilisation.

Major elements (as oxides) plotted against SiO2 for Nemrut glasses. Data from Table 4a in ESM. The symbol scheme is explained in Fig. 6. The grey field is for several units of the Cekmece Formation pumice and scoria fallout (Sumita and Schmincke, unpublished data). The dashed lines are for the melt compositional trends generated by MELTS modelling (Table 9); for the majority, the fit to the natural rocks is poor. The dashed line in the Al2O3 plot exemplifies the mixing of an intermediate magma with peralkaline rhyolite magma

Matrix glasses of more than one composition characterise the mixed magma rocks (e.g. samples 2008-07-03-03, 2009-07-19-06; Table 1). The largest range is found in 2009-07-19-06 which contains glass of mugearitic, benmoreitic and trachytic composition (55.87–62.50 wt% SiO2). In others, the compositional range reflects the ongoing crystallisation of the melt. For example, in 2009-07-16-05, the range is from mugearite to benmoreite and the glass rimming the phenocrysts becomes more silica-rich in the sequence ol–cpx–plag, evidence of the order of appearance of the phases.

Matrix glass and melt inclusions from the peralkaline trachytes and rhyolites are plotted in the classification diagram of Macdonald (1974) in Fig. 10a, along with data for glass shards in the compositionally zoned Nemrut Formation for comparison (Sumita and Schmincke 2013c). The majority are comendites, with some points just entering into the pantellerite field. Magmas evolving along a single liquid line of descent form relatively simple trends on this plot, as shown for various peralkaline suites on Fig. 10b. The Nemrut data are more complex; a larger group of analyses forms a trend extending from the comendite field into the pantellerite field, the trend being very similar to that of the Olkaria comendites in the Kenya Rift. A second group, which plots at higher FeO* contents for a given SiO2 value on Fig. 9, is transitional towards the trend for Pantellerian peralkaline rocks, plotting along a trend from comenditic trachyte towards pantellerite. The Nemrut trends would seem to converge at the composition 6 wt% FeO*, 9 wt% Al2O3.

a Peralkaline trachyte and rhyolite glasses from Nemrut plotted in the classification scheme for peralkaline silicic rocks of Macdonald (1974). One trend, including samples 2008-07-03-03 and 2009-07-14-06, extends from comendite to pantellerite; a parallel trend displaced to slightly higher Al2O3 concentrations includes the Nemrut Formation ignimbrite (NF) and some analyses from sample 2008-07-05-13; a third trend extends from comenditic trachyte to the comendite/pantellerite boundary. Data from Table 4a in ESM and Sumita and Schmincke (2013c, NF). b Generalised trends for various peralkaline suites, modified from Macdonald et al. (2011). The Nemrut data are shown as a light brown field

Çubukçu et al. (2012) reported a compositional gap in between 53 and 59 wt% SiO2 in the Nemrut eruptives (mainly lavas and subvolcanic rocks). The new glass data partially fill the gap, with several point analyses between 57 and 60 wt%. Nevertheless, intermediate compositions are scarce at the volcano, the typical situation in basalt–alkali–rhyolite sequences, as discussed below.

A puzzling feature of the Nemrut glass analyses, atypical of peralkaline silicic magmas, is the low abundance of halogens. Fluorine levels are lower than the detection limit of our microprobe technique (~700 ppm), and Cl levels are lower, and frequently much lower, than <0.3 wt%. There are four possible explanations: (1) the Nemrut magmas are genuinely halogen poor; (2) we have overlooked the presence of one or more halogen-rich phase in the glasses; Marshall et al. (1998), for example, recorded fluorite occurring as microphenocrysts in comendites of the Olkaria complex, Kenya; (3) the halogens have been largely removed by secondary hydration of the glass, which we suggested above was not a significant process in our study rocks; (4) the halogens were lost during pre- or syn-eruptive degassing. This last point is not consistent with experimental evidence that F, in particular, tends to partition into the melt phase during degassing (Carroll and Webster 1994) or with the compositional similarity between melt inclusions and matrix glasses in the Nemrut rocks (c.f. Neave et al. (2012) for several eruptions on Pantelleria).

Geothermobarometry

Coexisting FeTi oxides

Coexisting FeTi oxides occur in five samples (Table 1). Attempts to use them to calculate temperatures of equilibration and fO2 are hampered by the fact that in some cases the data do not pass the Bacon and Hirschmann (1988) test of equilibrium. This is partly due to the fact that some rocks are mixed magma products and the Mg/Mn ratios may have reequilibrated under the new temperature conditions. Also, the MgO levels in many oxides are very low, <0.1 wt%, and thus subject to significant analytical uncertainty. Samples where the coexisting oxides pass the Bacon and Hirschmann (1988) test are given in Table 7. The pairs either occur as inclusions in the same phenocryst or in the same glass clast, as noted in Table 7. Temperatures and fO2, calculated using QUILF85 within the ILMAT program of Lepage (2003), are in the range 875 °C, −13.82 for the trachyandesitic component of sample 2009-07-19-06, through 826–837 °C, −15.29 to −15.61 for the metaluminous rhyolite component of sample 2008-07-04-04, to 791 °C, −16.34 for comendite sample V-70 (2B-5H-5cc). One result of 898 °C, −13.63 for sample 2008-07-04-04 is taken to record the metaluminous trachyte component. The stated uncertainty of the temperature estimates is about ±25 °C (Andersen et al. 1993). The T–fO2 data indicate that the magmas evolved at or close to the FMQ buffer, as has been recorded in many peralkaline silicic suites, such as Kane Springs Wash, Nevada (Novak and Mahood (1986), Pantelleria, Italy (White et al. 2005), Eburru, Kenya (Ren et al. 2006), Pine Canyon, Texas (White et al. 2006) and Menengai, Kenya (Macdonald et al. 2011).

Clinopyroxene–liquid equilibria

The temperature estimates in Table 8 were based, where possible, on equilibrium pairs of pyroxene and rimming glass, or pyroxene–glass (melt) inclusions. Otherwise, average matrix glass and pyroxene compositions were used. The results are based on the models of Putirka (2008) and Masotta et al. (2013), some of which include recalibrations of the Putirka models for differentiated alkaline (including peralkaline) rocks. Recalculated clinopyroxene analyses for samples V-70 (2B-5H-5cc) and V-111 (2E-22A-1, 78–83 cm) lack a jadeite (Jd) component and therefore cannot be used to estimate T or P. For these models, it was assumed that the melt water content equalled the difference of the oxide total from 100 wt% and pressure was set at 1 kbar (column 1a) and 2 kbar (column 1b). Estimated errors are ±45 °C for Putirka (2008), ±31.4 °C for the recalibrated Putirka model (Masotta et al. 2013) and ±18.2 °C and ±1.15 kbar for the new models (Talk2012 and Palk2012) of Masotta et al. (2013).

The temperature estimates from the Masotta et al. (2013) model fall within the range from the original and recalculated Putirka (2008) models for the trachyandesitic component of sample 2009-07-16-05. Overall, the ranges from all models are: trachyandesite 1005–1097 °C; metaluminous rhyolite to comendite 748–809 °C (excluding the value of 815 °C); comendite to pantellerite 808–826 °C. The estimates are broadly compatible with those from coexisting oxides: 875 °C for the trachyandesitic component of sample 2009-07-19-06, through 898 and 837–826 °C for the metaluminous trachytic and rhyolitic components of sample 2008-07-04-04, respectively, to 791 °C for the comendite. The range in the rhyolites is broadly similar to that established by White et al. (2005) for peralkaline rhyolites of similar peralkalinity index (<1.3) from Pantelleria, Italy, but higher than those established for comenditic rhyolites of the Olkaria complex, Kenya (740–660 °C; Scaillet and Macdonald 2001). In a compilation of T–fO2 data for peralkaline trachytes and rhyolites, Macdonald (2012) showed that there is no simple relationship between temperature and either SiO2 content or peralkalinity and suggested that it reflected the role of water in depressing crystallisation temperatures. The relatively high temperatures recorded in the Nemrut peralkaline rhyolites might indicate that they were less volatile rich than the Olkaria rhyolites.

Pressure estimates derived from the Masotta et al. (2013) model are in the range 0.7–3.6 kbars, with an estimated error of ±1.15 kbar (Table 8). This broadly points to an upper crustal (<10 km) magma reservoir or reservoirs, consistent with previous estimates of the depth to peralkaline felsic reservoirs (e.g. Mahood 1984; Freundt and Schmincke 1995; Bohrson and Reid 1997; White et al. 2009; Neave et al. 2012).

Discussion

Significance of the intermediate composition melts for the Daly Gap

In some peralkaline oversaturated suites, there is an essentially complete series of melt compositions between basalt and trachyte (Socorro Island, Mexico, Bryan 1976; Bohrson and Reid 1995; Volcan Las Navajas, Mexico, Nelson and Hegre 1990; Terceira, Azores, Mungall and Martin 1995; Ascension, Weaver et al. 1996; Easter Island, Haase et al. 1997), although intermediate members, broadly corresponding to mugearites and benmoreites, are usually volumetrically minor, especially in continental volcanoes. However, on the oceanic island of Gran Canaria, one of the largest peralkaline centres, intermediate compositions remained effectively absent in the surface volcanics throughout the ca. four million years of its history (Schmincke 1969; Schmincke and Sumita 1998). In other suites, rocks of intermediate composition have been shown to be a result of mixing between mafic and salic magmas (Kane Springs Wash Caldera, Nevada, Novak and Mahood 1986; Pantelleria, Ferla and Meli 2006; Alid volcanic centre, Eritrea, Lowenstern et al. 2006).

Mixed magma intermediate products have also been recorded at the Gedemsa volcano, Ethiopia (Peccerillo et al. 2003) and the Olkaria complex, Kenya (Macdonald et al. 2008a); intermediate products were formed both by fractional crystallisation and by magma mixing. At Nemrut, Çubukçu et al. (2012) described benmoreites occurring as enclaves in intra-caldera comendites and ascribed their origin mainly to mingling between mafic and felsic magmas. However, it is clear from their bulk rock geochemical data (see, for example, the Al, Na, P, Ni plots in their Figs. 6, 7) that intermediate compositions were formed by both fractional crystallisation and magma mixing.

The absence or scarcity of intermediate magmas is the basis of the “Daly gap”. Several mechanisms, not mutually exclusive, for generating the gap have been proposed. (1) During the continuous crystallisation of basaltic magma towards trachyte, the intermediate melts occupy a narrow temperature interval where crystallisation is rapid and residual melt compositions change quickly, as a result of either the geometry of the phase relationships or undercooling in the reservoir (Bonnefoi et al. 1995; White et al. 2009; Dufek and Bachmann 2010). Rapid crystallisation may also be a result of the sinking of dense minerals, such as olivine and FeTi oxides (Neave et al. 2012). (2) In a study of high-level doleritic sills from the Silali volcano, Kenya, Macdonald et al. (1995) noted that significant proportions of intermediate magma are represented by the rims of zoned crystals in the dolerite. Similarly, Freundt-Malecha et al. (2001) found that intermediate compositions related to the P1 basalt–rhyolite–ignimbrite on Gran Canaria, Canary Islands, are represented by vast volumes of plutonic xenoliths in the ignimbrite. (3) Intermediate magmas tend to be denser and more viscous than hydrous silicic magmas in the system, tend to be discriminated against during eruption and are seen only as components of mixed magmas (Weaver 1977; Neave et al. 2012). (4) As a variant of mechanism 3, Rooney et al. (2012) suggested, on the basis of studies of the Chefe Donsa peralkaline pyroclastic deposits in Ethiopia, that intermediate magmas are formed by basaltic magma fractionating to form a crystal–liquid mush and may be extracted from the mush only when a rigid framework has formed.

The existence of minor melts of intermediate composition at Nemrut shows that the Daly gap was crossed, at least during some stages of evolution. The presence of compositionally zoned units, such as the Nemrut Formation, and of evidence for mixing between basalt, benmoreitic and trachytic magmas, as described above, might suggest that the trachytic–rhyolitic caps to the zoned reservoirs acted as a trap to intermediate magmas that were erupted only as components of mixed/mingled magmas.

Differentiation mechanisms

Compositional variation in the Nemrut suite, as expressed in the whole rocks, is a result of a combination of fractional crystallisation, magma mixing and volatile loss, and possibly minor loss of alkalis during secondary hydration of glass. An added complication is that some eruptive units may show signs of interaction with magmas from the neighbouring Süphan volcano. Sumita and Schmincke (2013c), for example, speculated that Süphan magmas might have occasionally entered the Nemrut system following the huge eruption of the Nemrut Formation fallout and subsequent pyroclastic flow.

The form of the compositional variation on the silica plots, particularly the inflections in almost all major oxides, points to fractional crystallisation being the dominant differentiation mechanism (Fig. 9). This is consistent with the continuous variation in phenocryst compositions (Figs. 5, 6). Using least squares mass balance estimations, Çubukçu et al. (2012) showed that it is possible to derive the sequence marginally trachyte and then comendite through fractional crystallisation of alkali basalt using the observed phenocryst assemblages.

The MELTS program (Ghiorso and Sack 1995) has been used here to attempt to trace in detail the compositional evolution of melts and phenocrysts between mugearites and peralkaline rhyolites. The starting composition was a melt inclusion of mugearitic composition in olivine (ESM Table 4, anal. 39). The liquid lines of descent were calculated at pressures of 1 and 3 kbar, with the oxygen fugacity set at FMQ. Temperatures ranged from 1200 °C (i.e. ~50 °C above the liquidus) to 700–800 °C. None of the models was very successful. The model closest to the compositional variation in the suite was for 3 kbar and the modelled trends are shown in Fig. 9. For Fe, Mg and Ca, the fit is reasonably good but for no other elements is the fit acceptable. The modelled feldspar compositions are, however, close to those in the natural rocks. The rhyolite-MELTS program (Gualda et al. 2012) was also used to model the liquid line of descent, using the same conditions and starting composition. It was less successful than MELTS; in particular, it did not replicate the complete range of feldspar compositions. Attempts to quantify the fractionation trends using MELTS and rhyolite-MELTS are hampered by the multi-lineage nature of the suite and by the difficulty in identifying equilibrium melt–phenocryst pairs.

Fractionation within the peralkaline rocks is now examined using the system Na2O–K2O–Al2O3–SiO2. In Fig. 11, the alkali ratio (K/(K + Na)) is plotted against (Si/3Al)-1, which is an index of silica excess with respect to an alkali feldspar composition (Roux and Varet 1975). The plot can be used to trace melt compositions as they evolve towards more silicic compositions and also shows, via melt–feldspar tie-lines, how the feldspar composition changes with melt composition. The Nemrut suite becomes peralkaline ((Si/3Al)-1 ≈ 0.2) dominantly through plagioclase fractionation (tie-line 1) followed by alkali feldspar fractionation (tie-lines 2 and 3). In the metaluminous to mildly peralkaline trachytes and rhyolites, alkali feldspar phenocrysts are more sodic than the melts and fractionation produces increasingly potassic residual melts. The tie-lines (4–6) then become increasingly steep and the most peralkaline melts crystallize feldspar more potassic than themselves: feldspar fractionation then generates increasingly sodic residual melts, the so-called orthoclase effect of Bailey and Schairer (1964). The rather flat distribution of points at a value of (Si/3Al)-1 equal to ~1.2 is probably a result of significant quartz crystallisation, which would tend to lower Si relative to Al. The dashed line broadly separates quartz-phyric rhyolites from rhyolites lacking quartz phenocrysts and is taken to represent the position of the natural analogue of the quartz–feldspar cotectic.

K/(K + Na) plotted against (Si/3Al)-1 for Nemrut glass (melt) compositions. Representative tie-lines show the relationships between melt and feldspar phenocryst compositions as the magmas became more evolved. The alkali feldspar attains the composition Or41–42, when it is more potassic than the coexisting melt and generates a trend of increasing Na/K ratios in residual melts. The dashed line marks the approximate position of the alkali feldspar–quartz cotectic, located from the appearance of quartz phenocrysts. Data for tie-lines 1–5: feldspars—Table 1c in ESM, columns AT, CY, G, CU, I; corresponding glasses—Table 1c in ESM, columns BM, EA, B, DK, T. Others may be drawn using the data specified in the Tables

The existence of two phenocryst populations in some rocks (Table 1) is strong evidence that they are a result of magma mixing, as already recognised by Çubukçu et al. (2012), Sumita and Schmincke (2013a, c) and Schmincke et al. (2014). In an extreme case, it was suggested above that plagioclase crystals with An >50 in peralkaline rhyolite 2009-07-14-06 were derived from a basaltic magma. In none of the major element plots is there any unequivocal evidence of magma mixing (Fig. 9). For example, in the strongly inflected SiO2–Al2O3 plot, no analyses plot on a tie-line between intermediate compositions (say, 60 wt% SiO2) and rhyolite. There is, however, more than one glass composition in individual samples, as is common in tephra samples.

The Nemrut plumbing system

Without precise estimates of pressures of melt equilibration and melt volatile contents, we cannot address the nature and location of the Nemrut storage reservoir(s) in any detail. However, there is some evidence as to the processes operative in the reservoir(s). First, the ~30 ka Nemrut Formation was a large-scale eruption from a chamber compositionally zoned from rhyolite to mugearite. The compositional variations are similar to those recorded in this report. Second, since ~190 ka, major eruptions appear to have occurred at intervals spaced some 20–40,000 years apart, which Sumita and Schmincke (2013a, c) interpreted as being the incubation times for the silicic magmas to develop into large eruptible volumes via volatile build-up. This regularity might point to repeated processes in a single reservoir. Third, magma mingling—and less common magma mixing—were ubiquitous processes (e.g. Figure 8a in Sumita and Schmincke 2013c), suggesting that rapid recharge by less evolved magma into a higher-level body helped to trigger the rhyolitic eruptions (Sumita and Schmincke 2013c; Schmincke et al. 2014). These features are consistent with the “Standard Model” of the evolution of silicic systems of Gualda and Ghiorso (2013), where a stably stratified magma chamber forms over thousands of years by crystal settling and upward migration of volatiles.

In contrast, the multi-lineage nature of the Nemrut magmas is perhaps more consistent with tapping multiple melt lenses contained within a much larger system, the “complex magma reservoirs” of Cashman and Giordano (2014). Further detailed petrological and geophysical work is in progress to provide better insights into the Nemrut magma system.

Conclusions

-

1.

The Nemrut volcano comprises multi-lineages, representing frequent reactivation of its plumbing system.

-

2.

Its open-system nature is also indicated by the abundant evidence of mingling and lesser true mixing between mafic, intermediate and silicic magmas.

-

3.

Residual melts in the rhyolites showed decreasing K contents with increasing degrees of evolution, unusually for a peralkaline silicic suite. The decrease is a result of the K-rich nature of the alkali feldspar phenocrysts in the most evolved rocks, up to Or41.

-

4.

The rocks are poor in halogens, also unusual in peralkaline suites. In contrast, they show abundant evidence for the exsolution of an enigmatic, unidentified Pb-rich phase.

-

5.

Two-oxide and clinopyroxene–melt geothermometry indicates that the intermediate-silicic magmas evolved in an upper crustal magma reservoir at temperatures between 1100 and 750 °C, at fO2 close to FMQ.

-

6.

Certain features of the Nemrut plumbing system point to magma evolution in a stably stratified chamber which forms over thousands of years by crystal settling and upward migration of volatiles. In contrast, the multi-lineage nature of the magmas is perhaps more consistent with tapping multiple melt lenses contained within a much larger system.

References

Andersen DJ, Lindsley DH, Davidson PM (1993) QUILF: a PASCAL program to assess equilibria among Fe–Mg–Mn–Ti oxides, pyroxenes, olivine, and quartz. Comput Geosci 19:1333–1350

Avanzinelli R, Bindi L, Menchetti S, Conticelli S (2004) Crystallisation and genesis of peralkaline magmas from Pantelleria Volcano, Italy: an integrated petrological and crystal-chemical study. Lithos 73:41–69

Bacon CR, Hirschmann MC (1988) Mg/Mn partitioning as a test for equilibrium between coexisting Fe–Ti oxides. Am Mineral 73:57–61

Bailey DK, Macdonald R (1970) Petrochemical variations among mildly peralkaline (comendite) obsidians from the oceans and continents. Contrib Mineral Petrol 28:340–351

Bailey DK, Schairer JF (1964) Feldspar-liquid equilibria in peralkaline liquids—the orthoclase effect. Am J Sci 262:1198–1206

Barberi F, Ferrara G, Santacroce R, Treuil M, Varet J (1975) A transitional basalt-pantellerite sequence of fractional crystallization, the Boina Centre (Afar Rift, Ethiopia). J Petrol 16:22–56

Bohrson WA, Reid MR (1995) Petrogenesis of alkaline basalts from Socorro Island, Mexico: Trace element evidence for contamination of ocean island basalt in the shallow ocean crust. J Geophys Res 100:24555–24576

Bohrson WA, Reid MR (1997) Genesis of silicic peralkaline volcanic rocks in an ocean island setting by crustal melting and open-system processes: Socorro Island, Mexico. J Petrol 38:1137–1166

Bonnefoi CC, Provost A, Albarède F (1995) The ‘Daly gap’ as a magmatic catastrophe. Nature 378:270–272

Boyce JW, Hervig RL (2009) Apatite as a monitor of late-stage magmatic processes at Volcán Irazú, Costa Rica. Contrib Mineral Petrol 157:135–145

Bryan WB (1976) A basalt-pantellerite association from Isla Socorro, Islas Revillagigedo, Mexico. In: Aoki H, Iizuka S (eds) Volcanoes and tectonosphere. Tokai University Press, Tokyo, pp 75–91

Carroll MR, Webster JD (1994) Solubilities of sulfur, noble gases, nitrogen, chlorine and fluorine in magmas. In: Carroll MR, Holloway JR (eds) Volatiles in magmas. Reviews in mineralogy, Mineral Soc Am 30:231–271

Cashman KV, Giordano G (2014) Calderas and magma reservoirs. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 288:28–45

Cherniak DJ (2000) Rare earth element diffusion in apatite. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 64:3871–3885

Civetta L, Antonio M, Orsi G, Tilton GR (1998) The geochemistry of volcanic rocks from Pantelleria Island, Sicily Channel: petrogenesis and characteristics of the mantle source region. J Petrol 39:1453–1491

Çubukçu HE, Ulusoy I, Aydar E, Ersoy O, Şen E, Gourgaud A, Guillou H (2012) Mt. Nemrut volcano (Eastern Turkey): temporal petrological evolution. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 209–210:33–60

Di Carlo I, Rotolo SG, Scaillet B, Buccheri V, Pichavant M (2010) Phase equilibrium constraints on pre-eruptive conditions of recent felsic explosive volcanism at Pantelleria Island, Italy. J Petrol 51:2245–2276

Dufek J, Bachmann O (2010) Quantum magmatism: magmatic compositional gaps generated by melt-crystal dynamics. Geology 38:687–690

Ferla P, Meli C (2006) Evidence of magma mixing in the ‘Daly Gap’ of alkaline suites: a case study from the enclaves of Pantelleria (Italy). J Petrol 47:1467–1507

Freundt A, Schmincke H-U (1995) Petrogenesis of rhyolite-trachyte-basalt composite ignimbrite P1, Gran Canaria, Canary Islands. J Geophys Res 100:455–474

Freundt-Malecha B, Schmincke H-U, Freundt A (2001) Plutonic rocks of intermediate composition on Gran Canaria: the missing link of the bimodal volcanic rock suite. Contrib Mineral Petrol 141:430–445

Ghiorso MS, Sack RO (1995) Chemical mass-transfer in magmatic processes. 4. A revised and internally consistent thermodynamic model for the interpolation of liquid-solid equilibria in magmatic systems at elevated temperatures and pressures. Contrib Mineral Petrol 119:197–212

Gualda GAR, Ghiorso MS (2013) The Bishop Tuff giant magma body: an alterantive to the Standard Model. Contrib Mineral Petrol 166:755–775

Gualda GAR, Ghiorso MS, Lemons RV, Carley TL (2012) Rhyolite-MELTS: a modified calibration of MELTS optimised for silica-rich, fluid-bearing magmatic systems. J Petrol 53:875–890

Haase KM, Stoffers P, Garbe-Schönberg CD (1997) The petrogenetic evolution of lavas from Easter Island and neighbouring seamounts, near-ridge hotspot volcanoes in the SE Pacific. J Petrol 38:785–813

Horn S, Schmincke H-U (2000) Volatile emission during the eruption of Baitoushan Volcano (China/North Korea) ca. 969 AD. Bull Volcanol 61:537–555

Keskin M (2003) Magma generation by slab steepening and break off beneath a subduction- accretion complex: an alternative model for collision-related volcanism of Eastern Anatolia, Turkey. Geophys Res Lett 30:8046. doi:10.1029/2003GL018019

Keskin M (2007) Eastern Anatolia: a hotspot in a collision zone without a mantle plume. Geol Soc Am Spec Pap 409:475–505

Kunzmann T (1999) The aenigmatite-rhönite mineral group. Eur J Mineral 11:743–756

Le Bas MJ, Le Maitre RW, Streickesen A, Zanettin B (1986) A chemical classification of volcanic rocks based on the total alkali-silica diagram. J Petrol 27:745–750

Lepage LD (2003) ILMAT: an Excel worksheet for ilmenite-magnetite geothermometry and geobarometry. Comput Geosci 29:673–678

Litt T, Anselmetti FS, Cağatay N, Kipfer R, Schmincke H-U, PalaeoVan scientific team (2011) A 500,000 year-long sedimentary archive drilled in Eastern Anatolia (Turkey): the PalaeoVan Drilling Project. Trans Am Geophy Union 92(51):477–479

Lowenstern JB, Mahood GA (1991) New data on magmatic H2O contents of antellerites, with implications for petrogenesis and eruptive dynamics at Pantelleria. Bull Volcanol 54:78–83

Lowenstern JB, Charlier BLA, Clynne MA, Wooden JL (2006) Extreme U-Th disequilibrium in rift-related basalts, rhyolites and granophyric granite and the timescale of rhyolite generation, intrusion and crystallization at Alid volcanic center, Eritrea. J Petrol 47:2105–2122

Macdonald R (1974) Nomenclature and petrochemistry of the peralkaline oversaturated extrusive rocks. Bull Volcanol 38:498–516

Macdonald R (2012) Evolution of peralkaline silicic complexes: lessons from the extrusive rocks. Lithos 152:11–22

Macdonald R, Davies GR, Upton BGJ, Dunkley PN, Smith M, Leat PT (1995) Petrogenesis of Silali volcano, Gregory Rift, Kenya. J Geol Soc Lond 152:703–720

Macdonald R, Marshall AS, Dawson JB, Hinton RW, Hill PG (2002) Chevkinite-group minerals from salic volcanic rocks of the East African Rift. Mineral Mag 66:287–299

Macdonald R, Bagiński B, Belkin HE, Dzierżanowski P, Jeżak L (2008a) Compositional variations in apatite from a benmoreite–peralkaline rhyolite volcanic suite, Kenya Rift Valley. Mineral Mag 72:1147–1161

Macdonald R, Belkin HE, Fitton JG, Rogers NW, Nejbert K, Tindle AG, Marshall AS (2008b) The roles of fractional crystallization, magma mixing, crystal much remobilization and volatile-melt interactions in the genesis of a young basalt-peralkaline rhyolite suite, the Greater Olkaria Volcanic Complex, Kenya Rift Valley. J Petrol 49:1515–1547

Macdonald R, Bagiński B, Leat PT, White JC, Dzierżanowski P (2011) Mineral stability in peralkaline silicic rocks: information from trachytes of the Menengai volcano. Lithos 125:553–568

Macdonald R, Davies GR, Bliss CM, Leat PT, Bailey DK, Smith RL (1987) Geochemistry of high-silica peralkaline rhyolites, Naivasha, Kenya RiftValley. J Petrol 28:979–1008

Mahood GA (1984) Pyroclastic rocks and calderas associated with strongly peralkaline magmatism. J Geophys Res 89:8540–8552

Mahood GA, Baker DR (1986) Experimental constraints on depths of fractionation of mildly alkali basalts and associated felsic rocks: Pantelleria, Strait of Sicily. Contrib Mineral Petrol 93:251–264

Mahood GA, Stimac JA (1990) Trace-element partitioning in pantellerites and trachytes. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 54:2257–2276

Marshall AS, Hinton RW, Macdonald R (1998) Phenocrystic fluorite in peralkaline rhyolites, Olkaria, Kenya Rift Valley. Mineral Mag 62:477–486

Masotta M, Mollo S, Freda C, Gaeta M, Moore G (2013) Clinopyroxene–liquid thermometers and barometers specific to alkaline differentiated magmas. Contrib Mineral Petrol 166:1545–1561

Mungall JE, Martin RF (1995) Petrogenesis of basalt-comendite and basalt-pantellerite series, Terceira, Azores, and some implications for the origin of ocean-island rhyolites. Contrib Mineral Petrol 119:43–55

Neave DA, Fabbro G, Herd RA, Petrone CM, Edmonds M (2012) Melting, differentiation and degassing at the Pantelleria volcano, Italy. J Petrol 53:637–663

Nekvasil H, Dondolini A, Horn J, Filiberto J, Long H, Lindsley DH (2004) The origin and evolution of silica-saturated alkalic suites: an experimental study. J Petrol 45:693–721

Nelson SA, Hegre J-A (1990) Volcan Las Navajas, a Pliocene–Pleistocene trachyte/peralkaline rhyolite volcano in the northwestern Mexican volcanic belt. Bull Volcanol 52:186–202

Novak SW, Mahood GA (1986) Rise and fall of a basalt-trachyte-rhyolite magma system at the Kane Springs Wash Caldera, Nevada. Contrib Mineral Petrol 94:352–373

Pearce JA, Bender JF, De Long SE, Kidd WSF, Low PJ, Güner Y, Şaroğlu F, Yilmaz Y, Moorbath S, Mitchell JG (1990) Genesis of collision volcanism in eastern Anatolia, Turkey. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 44:189–229

Peccerillo A, Barberio MR, Yirgu G, Ayalew D, Barbieri M, Wu TW (2003) Relationships between mafic and peralkaline silicic magmatism in continental rift settings: a petrological, geochemical, and isotopic study of the Gedemsa volcano, central Ethiopian rift. J Petrol 44:2002–2032

Pouchou JL, Pichoir JF (1991) Quantitative analysis of homogeneous or stratified microvolumes applying the model ‘PAP’. In: Heinrich KFJ, Newbury DE (eds) Electron probe quantification. Plenum Press, New York, pp 31–75

Putirka K (2008) Thermobarometers and barometers for volcanic systems. In: Putirka K, Tepley F (eds) Minerals, inclusions and volcanic processes. Rev Mineral Petrol 69:61–120

Ren M, Omenda PA, Anthony EA, White JC, Macdonald R, Bailey DK (2006) Application of the QUILF thermobarometer to the peralkaline trachytes and pantellerites of the Eburru volcanic complex, East African Rift, Kenya. Lithos 91:109–124

Rooney TO, Hart WK, Hall CM, Ayalew D, Ghiorso MS, Hidalgo P, Yirgu G (2012) Peralkaline magma evolution and the tephra record in the Ethiopian Rift. Contrib Mineral Petrol 164:407–426

Roux J, Varet J (1975) Alkali feldspar liquid equilibrium relationships in peralkaline oversaturated systems and volcanic rocks. Contrib Mineral Petrol 49:67–81

Scaillet B, Macdonald R (2001) Phase relations of peralkaline silicic magmas and petrogenetic implications. J Petrol 42:825–845

Scaillet B, Macdonald R (2003) Experimental constraints on the relationships between peralkaline rhyolites of the Kenya rift valley. J Petrol 44:1867–1894

Scaillet B, Macdonald R (2006) Experimental constraints on pre-eruption conditions of pantelleritic magmas: evidence from the Eburru complex, Kenya Rift. Lithos 91:95–108

Schmincke H-U (1969) Ignimbrite sequence on Gran Canaria. Bull Volcanol 33:1199–1219

Schmincke H-U, Sumita M (1998) Volcanic evolution of Gran Canaria reconstructed from apron sediments: Synthesis of VICAP project drilling (ODP Leg 157). In: Weaver PPE, Schmincke H-U, Firth JV, Duffield WA (eds) Proc ODP, Sci Results 157:443–469

Schmincke H-U, Sumita M, Paleovan scientific team (2014) Impact of volcanism on the evolution of Lake Van (eastern Anatolia). III. Periodic (Nemrut) vs. episodic (Süphan) explosive eruptions and climate forcing reflected in a tephra gap between ca. 14 ka and ca. 30 ka. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 285:195–213

Şenğor AMC, Özeren S, Genç T, Zor E (2003) East Anatolian high plateau as a mantle- supported, north-south shortened domal structure. Geophy Res Lett 30:8045. doi:10.1029/2003GL017858

Smith RL (1979) Ash-flow magmatism. In: Chapin CE, Elston WE (eds) Ash-flow tuffs. Geol Soc Am Spec Pap 180:5–27

Stockhecke M, Sturm M, Brunner I, Schmincke H-U, Sumita M, Kipfer R, Cukur D, Kwiecien O, Anselmetti FS (2014) Sedimentary evolution and environmental history of Lake Van (Turkey) over the past 600,000 years. Sedimentology. doi:10.1111/sed12118

Sumita M, Schmincke H-U (2013a) Impact of volcanism on the evolution of Lake Van II. Temporal evolution of Nemrut Volcano (eastern Anatolia) during the past ca. 0.4 Ma. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 253:15–34

Sumita M, Schmincke H-U (2013b) Erratum to “Impact of volcanism on the evolution of Lake Van II: temporal evolution of explosive volcanism of Nemrut Volcano (eastern Anatolia) during the past ca. 0.4 Ma”. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 253:131–133

Sumita M, Schmincke H-U (2013c) Impact of volcanism on the evolution of Lake Van I: evolution of explosive volcanism of Nemrut Volcano (eastern Anatolia) during the past >400,000 years. Bull Volcanol 75:1–32

Tepper JH, Kuehner SC (1999) Complex zonation in apatite from the Idaho batholith: a record of magma mixing and intracrystalline trace element diffusion. Am Mineral 84:581–595

Troll V, Sachs PM, Schmincke H-U, Sumita M (2003) The REE-Ti mineral chevkinite in comenditic magmas from Gran Canaria, Spain: a SYXRF-probe study. Contrib Mineral Petrol 145:730–741

Trua T, Deniel C, Mazzuoli R (1999) Crustal control in the genesis of Plio-Quaternary bimodal magmatism of the Main Ethiopian Rift (MER): geochemical and isotopic (Sr, Nd, Pb) evidence. Chem Geol 155:201–231

Watson EB, Harrison TM, Ryerson FJ (1985) Diffusion of Sm, Sr, and Pb in fluorapatite. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 49:1813–1823

Weaver SD (1977) The Quaternary caldera volcano Emuruangogolak, Kenya Rift, and the petrology of a bimodal ferrobasalt–pantelleritic trachyte association. Bull Volcanol 40:200–230

Weaver B, Kar A, Davidson J, Colucci M (1996) Geochemical characteristics of volcanic rocks from Ascension Island, south Atlantic Ocean. Geothermics 25:449–470

White JC, Ren M, Parker DF (2005) Variation in mineralogy, temperature, and oxygen fugacity in a suite of strongly peralkaline lavas and tuffs, Pantelleria, Italy. Canad Mineral 43:1331–1347

White JC, Benker SC, Ren M, Urbanczyk KM, Carrick DW (2006) Petrogenesis and tectonic setting of the peralkaline Pine Canyon caldera, Trans-Pecos Texas, USA. Lithos 91:74–94

White JC, Parker DF, Ren M (2009) The origin of trachyte and pantellerite from Pantelleria, Italy: insights from major element, trace element, and thermodynamic modelling. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 179:33–55

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Piotr Dzierżanowski and Ms. Lidia Jeżak for assistance with electron microprobe analyses and Marcin Stachowicz for help with Raman spectroscopy measurements. We also thank Tyrone Rooney, Othmar Müntener and an anonymous referee for extremely helpful and insightful comments on the original manuscript. Some initial funding on Nemrut was provided to HUS by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. Further funding was supplied by University of Warsaw grant BSt 160600/4-31-IGMiP-2012. Drill core samples were obtained in the framework of the ICDP Paleovan drilling project 2010. The Paleovan drilling campaign was funded by the International Continental Scientific Drilling Program (ICDP), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), the Swiss National Science Foundation and the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (Tübitak). We acknowledge the cooperation and generous supply of sundry borehole data from the ICDP PalaeoVan scientific team.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Othmar Müntener.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Macdonald, R., Sumita, M., Schmincke, HU. et al. Peralkaline felsic magmatism at the Nemrut volcano, Turkey: impact of volcanism on the evolution of Lake Van (Anatolia) IV. Contrib Mineral Petrol 169, 34 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00410-015-1127-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00410-015-1127-6