Abstract

Introduction

Certain types of oral contraceptives can produce favorable effects on lipid metabolism and vascular tone, while others have potentially detrimental effects. Endogenous and exogenous hormones exert different effects on high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) depending on the type, combination, and dose of the hormone. The estrogenic and progestogenic effects of exogenous hormones on HDL and LDL are inconsistent. Studying surrogate end points (LDL, HDL levels) may provide a misleading picture of OCs.

Methods

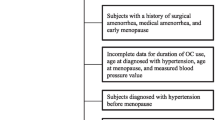

Medicaid data from 2000 to 2013 were used to assess the relationship between the type of OCs and CVD incidence. Multivariable logistic regression was used to model relationships between cardiovascular disease and OC use adjusting for potential confounders.

Results

Compared to combined oral contraceptives (COC), progestin-only oral contraceptives (POC) were associated with decreased heart disease and stroke incidence after adjusting for important covariates (OR 0.74; 95 % CI 0.57, 0.97 and OR 0.39; 95 % CI 0.16, 0.95, respectively). However, there was a positive association between POC + COC and both heart disease and stroke incidence (OR 2.28; 95 % CI 1.92, 2.70 and OR 2.12; 95 % CI 1.34, 3.35, respectively).

Conclusion

In light of an association between POC use and decreased heart disease and stroke, women’s CVD risk factors should be carefully considered when choosing which OC to use. Baseline CVD risk should be a part of the discussion between women and their primary care providers when making choices regarding OCs.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Anders CK, Johnson R, Litton J, Phillips M, Bleyer A (2009) Breast cancer before age 40 years. Semin Oncol 36:237–249

Go AS et al (2013) Heart disease and stroke statistics—2013 update a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 127:e6–e245

CDC (2013) US selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use, 2013

Mosca L, Barrett-Connor E, Wenger NK (2011) Sex/gender differences in cardiovascular disease prevention what a difference a decade makes. Circulation 124:2145–2154

Albert MA, Torres J, Glynn RJ, Ridker PM (2004) Perspective on selected issues in cardiovascular disease research with a focus on Black Americans. Circulation 110:e7–e12

Samson M, Trivedi T, Khosrow H (2015) Telestroke centers as an option for addressing geographical disparities in access to stroke care in South Carolina, 2013. Prev Chronic Dis 12:150418. doi:10.5888/pcd12.150418

Shufelt CL, Merz CNB (2009) Contraceptive hormone use and cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 53:221–231

Miller VT (1994) Lipids, lipoproteins, women and cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis 108(Supplement):S73–S82

Berenson AB, Rahman M, Wilkinson G (2009) Effect of injectable and oral contraceptives on serum lipids. Obstet Gynecol 114:786–794

Crook D, Godsland IF, Wynn V (1988) Oral contraceptives and coronary heart disease: modulation of glucose tolerance and plasma lipid risk factors by progestins. Am J Obstet Gynecol 158:1612–1620

Finks SW (2010) Cardiovascular disease in women. Lanexa, pp 179–199. https://www.accp.com/docs/bookstore/psap/p7b01sample03.pdf

Gouva L, Tsatsoulis A (2004) The role of estrogens in cardiovascular disease in the aftermath of clinical trials. Horm Athens Greece 3:171–183

Rosano GM, Sarais C, Zoncu S, Mercuro G (2000) The relative effects of progesterone and progestins in hormone replacement therapy. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl 15(Suppl 1):60–73

Dumeaux V, Alsaker E, Lund E (2003) Breast cancer and specific types of oral contraceptives: a large Norwegian cohort study. Int J Cancer J Int Cancer 105:844–850

Chakhtoura Z et al (2009) Progestogen-only contraceptives and the risk of stroke a meta-analysis. Stroke 40:1059–1062

Graff-Iversen S, Tonstad S (2002) Use of progestogen-only contraceptives/medications and lipid parameters in women age 40 to 42 years: results of a population-based cross-sectional Norwegian Survey. Contraception 66(1):7–13

Herrington DM, Howard TD (2003) From presumed benefit to potential harm—hormone therapy and heart disease. N Engl J Med 349:519–521

AIM-High (2011) Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterol levels receiving intensive statin therapy. N Engl J Med 365:2255–2267

Marchbanks PA et al (2002) Oral contraceptives and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med 346:2025–2032

ACOG (2006) ACOG practice bulletin no 73: use of hormonal contraception in women with coexisting medical conditions. Obstet Gynecol 107:1453–1472

FSRH (2011) Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare Clinical Guidance: combined hormonal contraception clinical effectiveness unit. Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare 1–19

Samson M, Porter N, Orekoya O, Bennett C, Hebert J, Adams S, Steck S (2015) Progestin and breast cancer risk: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat 155(1):3–12. doi:10.1007/s10549-015-3663-1

Montresor-López JA et al (2015) Short-term exposure to ambient ozone and stroke hospital admission: a case-crossover analysis. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. doi:10.1038/jes.2015.48

Mujib M, Zhang Y, Feller MA, Ahmed A (2011) Evidence of a ‘heart failure belt’ in the southeastern United States. Am J Cardiol 107:935–937

Medicaid (2015) South Carolina Medicaid. http://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-State/south-carolina.html. Accessed 8 Apr 2015

MLTSS (2012) Total medicaid enrollment in managed long-term services and supports (MLTSS). http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-medicaid-enrollment-in-managed-long-term-services-and-supports/.Accessed 2 Dec 2015

Samson M et al (2015) Trends in oral contraceptive use by race and ethnicity in South Carolina among Medicaid-enrolled women

Bousser MG, Kittner SJ (2000) Oral contraceptives and stroke. Ceph Int J Headache 20:183–189

Roach REJ et al (2015) Cochrane database of systematic reviews. Wiley, Hoboken. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011054.pub2/abstract. Accessed 30 Oct 2015

Kemmeren JM et al (2002) Risk of arterial thrombosis in relation to oral contraceptives (RATIO) study: oral contraceptives and the risk of ischemic stroke. Stroke J Cereb Circ 33:1202–1208

Fox K, Merrill JC, Chang HH, Califano JA (1995) Estimating the costs of substance abuse to the Medicaid hospital care program. Am J Public Health 85:48–54

Westover AN, McBride S, Haley RW (2007) Stroke in young adults who abuse amphetamines or cocaine: a population-based study of hospitalized patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64:495–502

Schwartz SM et al (1998) Stroke and use of low-dose oral contraceptives in young women a pooled analysis of two US studies. Stroke 29:2277–2284

Szklo M, Nieto J (2012) Epidemiology. Jones & Bartlett Publishers, Burlington. ISBN 978-1-4496-0469-1

Bhandari VK, Kushel M, Price L, Schillinger D (2005) Racial disparities in outcomes of inpatient stroke rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 86:2081–2086

Morales KH et al (2014) Patterns of weight change in black Americans: pooled analysis from three behavioral weight loss trials. Obesity 22:2632–2640

Greenlund KJ et al (1997) Associations of oral contraceptive use with serum lipids and lipoproteins in young women: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Ann Epidemiol 7:561–567

Chomistek AK et al (2015) Healthy lifestyle in the primordial prevention of cardiovascular disease among young women. J Am Coll Cardiol 65:43–51

Chasan-Taber L et al (1996) Prospective study of oral contraceptives and hypertension among women in the United States. Circulation 94:483–489

Longstreth WT Jr, Swanson PD (1984) Oral contraceptives and stroke. Stroke 15(4):747–750. doi:10.1161/01.STR.15.4.747S

Gelberg LG, Browner C, Lehano E, Arangua L (2004) Access to women’s health care: a qualitative study of barriers perceived by homeless women. Women Health 40:87–100

NWLC (2015) The past and future in women’s health: a ten-year review and the Promise of the Affordable Care Act and Other Federal Initiatives|Health Care Report Card. http://hrc.nwlc.org/past-and-future. Accessed 30 Oct 2015

FSRH (2009) Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare Clinical Guidance: Progestogen-only Pills Clinical Effectiveness Unit. Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare 1–19

Samson ME, Adams SA, Orekoya O, Hebert JR (2015) Understanding the association of type 2 diabetes mellitus and breast cancer among african-american and European-American populations in South Carolina. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 1–9. doi:10.1007/s40615-015-0173-0

Samson M, Porter N, Hurley D, Adams S, Eberth J (2016) Disparities in breast cancer incidence, mortality, and quality of care among African American and European American women in South Carolina. Southern Medical Journal 109(1):24–30. doi:10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000396

World Health Organization (2015) Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 5th edn. World Health Organization, Geneva

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None to disclose, and we had control of only secondary data through Medicaid.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Samson, M.E., Adams, S.A., Merchant, A.T. et al. Cardiovascular disease incidence among females in South Carolina by type of oral contraceptives, 2000–2013: a retrospective cohort study. Arch Gynecol Obstet 294, 991–997 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-016-4143-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-016-4143-5