Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to examine whether cesarean section in the first pregnancy is associated with the success or failure of programmed fetal growth phenotypes or patterns in the subsequent pregnancy.

Methods

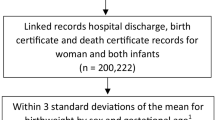

We analyzed data from a population-based retrospective cohort of singleton deliveries that occurred in the state of Missouri from 1978 to 2005 (n = 1,224,133). The main outcome was neonatal mortality, which was used as an index of the success of fetal programming. Cox proportional hazard and logistic regression models were used to generate point estimates and 95% confidence intervals.

Results

Mothers delivering by cesarean section in the first pregnancy were less likely to deliver subsequent appropriate-for-gestational-age (AGA) neonates (OR 0.91, 95% CI 0.89–0.92) when compared with mothers delivering vaginally. Of the 1,457 neonatal deaths in the second pregnancy, 383 early neonatal and 95 late neonatal deaths were to mothers with cesarean section deliveries in the first pregnancy. When compared with women with a previous vaginal delivery, AGA neonates of women with a primary cesarean section had 20% increased risk of both neonatal (OR 1.20, 95% CI 1.05–1.37) and early neonatal (OR 1.23, 95% CI 1.05–1.43) death.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that previous cesarean section is a risk factor for neonatal mortality among AGA infants of subsequent pregnancy. Future prospective studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Heron M et al (2010) Annual summary of vital statistics: 2007. Pediatrics 125(1):4–15

Chu SY et al (2007) Maternal obesity and risk of cesarean delivery: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev 8(5):385–394

Getahun D et al (2009) Racial and ethnic disparities in the trends in primary cesarean delivery based on indications. Am J Obstet Gynecol 4: 422e1–422e7

Paramsothy P et al (2009) Interpregnancy weight gain and cesarean delivery risk in women with a history of gestational diabetes. Obstet Gynecol 113(4):817–823

Patel RR et al (2005) Prenatal risk factors for caesarean section. Analyses of the ALSPAC cohort of 12, 944 women in England. Int J Epidemiol 34(2):353–367

Bailit JL, Love TE, Mercer B (2004) Rising cesarean rates: are patients sicker? Am J Obstet Gynecol 191(3):800–803

MacDorman MF et al (2006) Infant and neonatal mortality for primary cesarean and vaginal births to women with “no indicated risk”, United States, 1998–2001 birth cohorts. Birth 33(3):175–182

Menacker F (2005) Trends in cesarean rates for first births and repeat cesarean rates for low-risk women: United States, 1990–2003. Natl Vital Stat Rep 54(4):1–8

Smith GC et al (2002) Risk of perinatal death associated with labor after previous cesarean delivery in uncomplicated term pregnancies. JAMA 287(20):4684–4690

Smith GC, Pell JP, Dobbie R (2003) Caesarean section and risk of unexplained stillbirth in subsequent pregnancy. Lancet 362(9398):1779–1784

Towner D et al (1999) Effect of mode of delivery in nulliparous women on neonatal intracranial injury. N Engl J Med 341(23):1709–1714

Salihu HM et al (2006) Risk of stillbirth following a cesarean delivery: Black–White disparity. Obstet Gynecol 107(2 Pt 1):383–390

Martin J et al (2003) Development of the matched multiple birth file. In: 1995–1998 matched multiple birth dataset, NCHS CD-ROM series 21, no. 13a. National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville

Herman AA et al (1997) Data linkage methods used in maternally-linked birth and infant death surveillance datasets from the United States (Georgia, Missouri, Utah and Washington State), Israel, Norway, Scotland and Western Australia. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 11(Suppl 1):5–22

Alexander GR et al (1998) What are the fetal growth patterns of singletons, twins, and triplets in the United States? Clin Obstet Gynecol 41(1):114–125

Taffel S, Johnson D, Heuser R (1982) A method of imputing length of gestation on birth certificates. Vital Health Stat 2 93:1–11

Piper JM et al (1993) Validation of 1989 Tennessee birth certificates using maternal and newborn hospital records. Am J Epidemiol 137(7):758–768

Wingate MS et al (2007) Comparison of gestational age classifications: date of last menstrual period vs. clinical estimate. Ann Epidemiol 17(6):425–430

Salihu HM et al (2008) AGA-primed uteri compared with SGA-primed uteri and the success of subsequent in utero fetal programming. Obstet Gynecol 111:935–943

Salihu HM et al (2009) Success of programming fetal growth phenotypes among obese women. Obstet Gynecol 114:333–339

Alexander GR, Cornely DA (1987) Prenatal care utilization: its measurement and relationship to pregnancy outcome. Am J Prev Med 3(5):243–253

Alexander GR, Kotelchuck M (1996) Quantifying the adequacy of prenatal care: a comparison of indices. Public Health Rep 111(5):408–418

Herman AA, Yu KF (1997) Adolescent age at first pregnancy and subsequent obesity. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 11(Suppl 1):130–141

Parker JD, Abrams B (1992) Prenatal weight gain advice: an examination of the recent prenatal weight gain recommendations of the Institute of Medicine. Obstet Gynecol 79(5 Pt 1):664–669

Ananth CV et al (2009) Recurrence of fetal growth restriction in singleton and twin gestations. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 22(8):654–661

Okah FA et al (2010) Risk factors for recurrent small-for-gestational-age birth. Am J Perinatol 27(1):1–7

Walsh CA et al (2007) Recurrence of fetal macrosomia in non-diabetic pregnancies. J Obstet Gynaecol 27(4):374–378

Daltveit AK et al (2008) Cesarean delivery and subsequent pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol 111:1327–1334

Hemminki E, Shelley J, Gissler M (2005) Mode of delivery and problems in subsequent births: a register-based study from Finland. AJOG 193:169–177

Kannare R et al (2007) Risks of adverse outcomes in next birth after a first cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol 109:270–276

Kristensen S et al (2007) SGA subtypes and mortality risk among singleton births. Early Hum Dev 83:99–105

Lydon-Rochelle M et al (2001) First-birth cesarean and placental abruption or previa at second birth. Obstet Gynecol 97(5 Pt 1):765–769

Hemminki E, Meriläinen J (1996) Long-term effects of cesarean sections: ectopic pregnancies and placental problems. Am J Obstet Gynecol 174(5):1569–1574

Gardosi J, Francis A (2009) Adverse pregnancy outcome and association with small for gestational age birthweight by customized and population-based percentiles. Am J Obstet Gynecol 201(1):28.e1–28.e8

Gardosi J (2006) New definition of small for gestational age based on fetal growth potential. Horm Res 65(Suppl 3):15–18

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a Grant from the Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute (FAMRI: 024008) to the first author (Hamisu Salihu, MD, PhD). The funding agency did not play any role in any aspect of the study. We thank the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services for providing the data files used in this study.

Conflict of interest

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Salihu, H.M., Bowen, C.M., Wilson, R.E. et al. The impact of previous cesarean section on the success of future fetal programming pattern. Arch Gynecol Obstet 284, 319–326 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-010-1665-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-010-1665-0