Abstract

Objective

This paper presents a systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of aquatic exercise for treatment of knee osteoarthritis (OA).

Methods

PubMed, the Cochrane Library, Embase, CAMbase, and the Web of Science were screened through to June 2014. Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing aquatic exercise with control conditions were included. Two authors independently selected trials for inclusion, assessed the included trials, and extracted data. Outcome measures included pain, physical function, joint stiffness, quality of life (QOL), and safety. Pooled outcomes were analyzed using standardized mean difference (SMD).

Results

There is a lack of high quality studies in this area. Six RCTs (398 participants) were included. There was moderate evidence for a moderate effect on physical function in favor of aquatic exercise immediately after the intervention, but no evidence for pain or QOL when comparing aquatic exercise with nonexercise. Only one trial reported 3 months of follow-up measurements, which demonstrated limited evidence for pain improvement with aquatic exercise and no evidence for QOL or physical function when comparing aquatic exercise with nonexercise. There was limited evidence for pain improvement with land-based exercise and no evidence for QOL or physical function, when comparing aquatic exercise with land-based exercise according to follow-up measurements. No evidence was found for pain, physical function, stiffness, QOL, or mental health with aquatic exercise immediately after the intervention when comparing aquatic exercise with land-based exercise. Two studies reported aquatic exercise was not associated with serious adverse events.

Conclusion

Aquatic exercise appears to have considerable short-term benefits compared with land-based exercise and nonexercise in patients with knee OA. Based on these results, aquatic exercise is effective and safe and can be considered as an adjuvant treatment for patients with knee OA. Studies in this area are still too scarce and too short-term to provide further recommendations on how to apply this therapy.

Zusammenfassung

Ziele

In der vorliegenden systematischen Übersicht und Metaanalyse wurde die Wirksamkeit von Wassergymnastik in der Behandlung der Kniegelenksarthrose untersucht.

Methoden

PubMed, die Cochrane Library, Embase, CAMbase und das Web of Science wurden bis Juni 2014 durchsucht. Eingeschlossen wurden nur randomisierte, kontrollierte Studien (RCT), in denen Wassergymnastik mit Kontrollbedingungen verglichen wurde. Zwei Autoren schlossen unabhängig Studien ein, prüften diese und extrahierten Daten. Zu den Studienendpunkten gehörten Schmerz, körperliche Funktionsfähigkeit, Gelenksteifigkeit, Lebensqualität und Sicherheit. Die gepoolten Ergebnisse wurden anhand standardisierter Mittelwertdifferenzen (SMD) analysiert.

Ergebnisse

Es mangelt an qualitativ hochwertigen Studien zur beschriebenen Thematik. Sechs RCT mit 398 Teilnehmern wurden eingeschlossen. Die Analyse ergab eine mäßige Evidenz dafür, dass Wassergymnastik verglichen mit dem Verzicht auf Bewegungsübungen einen moderaten Effekt auf die körperliche Funktionsfähigkeit unmittelbar nach der Anwendung hat; in Bezug auf Schmerz oder Lebensqualität ließ sich dagegen keine Wirkung belegen. Nur in einer Studie wurden für 3 Monate Follow-up-Messungen durchgeführt. Diese ergaben eine begrenzte Evidenz für eine Schmerzbesserung bei Wassergymnastik und keinen Beleg für einen Effekt auf die Lebensqualität oder körperliche Funktionsfähigkeit, wenn Wassergymnastik mit dem Verzicht auf Bewegungsübungen verglichen wurde. Gemäß den Follow-up-Messungen gab es eine eingeschränkte Evidenz für eine Schmerzbesserung bei Trockengymnastik im Vergleich zu Wassergymnastik, hinsichtlich der Lebensqualität und körperlichen Funktionsfähigkeit fand sich keine Evidenz. In Bezug auf Schmerz, die körperliche Funktionsfähigkeit, Steifigkeit, Lebensqualität und psychische Verfassung fand sich kein Effekt der Wassergymnastik direkt nach Anwendung im Vergleich zu Trockengymnastik. In zwei Studien war angegeben, dass Wassergymnastik nicht mit schweren unerwünschten Ereignissen verbunden war.

Schlussfolgerungen

Verglichen mit Trockengymnastik und dem Verzicht auf Bewegungsübungen scheint Wassergymnastik kurzzeitig von beträchtlichem Nutzen für Patienten mit Kniegelenksarthrose zu sein. Auf der Grundlage dieser Ergebnisse ist die Methode wirksam und sicher. Sie kann als unterstützende Maßnahme bei Kniegelenksarthrose angesehen werden. Da es in diesem Themenbereich noch immer zu wenige Studien gibt und die Studiendauer zu knapp bemessen ist, sind weitergehende Empfehlungen zur Anwendung der Wassergymnastik nicht möglich.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most prevalent rheumatic disease, causing degenerative changes in cartilage and the periarticular area [1]; the knee is the most commonly affected joint. The most prominent symptom of knee OA is pain, while reduction in quality of life (QOL), loss of physical function, and muscle weakness are also often associated [2, 3]. In addition, loss of productivity and personal economic strain are associated with ongoing care and disease management [4]. Therapeutic exercise is recommended in numerous guidelines as a nonpharmacologic treatment for knee OA [5, 6, 7].

Aquatic exercise, which utilizes the characteristics of water to promote health, has a long history and is becoming more popular. Motion against water resistance results in increased muscle tone, power development, and improved endurance [8]. Water also reduces weight bearing due to the property of buoyancy [9]. The heating effect of water temperature has been reported to ease soft tissue contracture, reduce pain, and relieve muscle spasms and fatigue [8, 10, 11]. Since aquatic exercise is easier on the body, the practice of exercise feels better and is perceived to be more enjoyable—and pleasurable exercise appears to improve QOL [12, 13].

Several previous systematic reviews have summarized the effects of aquatic exercise, but they either included mixed populations (e.g., including individuals with chronic diseases, such as hip OA) [14, 15, 16, 17] or were nonrandomized controlled trials [18]. However, existing clinical practice guidelines uniformly recommend aquatic exercise for treatment of knee OA [5, 19].

It is important to verify the evidence for aquatic exercise’s effect on improving physical function, QOL, and pain in individuals with knee OA. A systematic review of all randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to date would determine whether aquatic exercise is effective in improving outcomes in individuals with knee OA.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Studies were eligible if they were RCTs.

Types of participants

Patients with primary knee OA were eligible. Diagnosis had to meet the classification criteria of the American College of Rheumatology [20, 21]. No further restrictions were made regarding disease duration or intensity.

Types of interventions

Studies that compared aquatic exercise to no treatment, usual care, or any other active treatment were eligible. All types of exercise developed in a therapeutic/heated indoor pool were eligible. Co-interventions other than exercise in a pool were allowed.

Types of outcome measures

According to the core set of outcome measures defined by Outcome Measures in Rheumatology Clinical Trials [22], studies were eligible if they assessed at least one of the following outcome measures: pain, physical function, or joint stiffness. If available, data on QOL and safety served as secondary outcome measures.

Search methods for identification of studies

Two authors (Meili Lu and Wenting Wang) independently completed a search of electronic databases. The following electronic databases were searched from their commencement through to June 2014: PubMed, the Cochrane Library, Embase, CAMbase, and the Web of Science. The literature search was conducted around search terms for aquatic exercise and knee OA, and adapted for each database as necessary. For PubMed, the search strategy was as follows: “(balneology [MeSH Terms] OR balneology [All Fields] OR balneotherapy [All Fields]) OR (hydrotherapy [MeSH Terms] OR hydrotherapy [All Fields] OR aquatic exercise [All Fields] OR pool exercise [All Fields] OR water exercise [All Fields]) AND (knee osteoarthritides [All Fields] OR knee osteoarthritis [All Fields] OR osteoarthritides of knees [All Fields] OR osteoarthritis of knees [All Fields] OR osteoarthritis, knee [MeSH Terms])”.

For further articles, the reference lists of articles were searched. There was no restriction on language.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

After removal of duplicate records, two authors (Yingjie Zhang and Zhen He) independently screened the title, abstract, keywords, and publication type of all records obtained from the described searches. Disagreement or uncertainty was resolved by discussion with a third author (Youxin Su). The potentially eligible studies were obtained by hardcopy and read in detail, and those deemed eligible were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis. Studies in which characteristics were not clearly described or data were missing, the authors of the study were contacted for clarification.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

In order to ensure that variation was not caused by the study design or execution, risk of bias was assessed independently by two authors (Lu Sheng and Changyan Liu) using the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [23]. The domains recommended for assessing risk of bias in studies included selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias, and other bias. Studies that met low risk of bias in all key domains were rated as having low risk of bias, those that met unclear risk of bias in one or more key domains were rated as having unclear risk of bias, and those that met high risk of bias in one or more key domains were rated as having high risk of bias. Where study data were inconclusive, trial authors were contacted for further details. Uncertainty or disagreement was resolved by discussion with a third author (Feiwen Liu).

Analyses and presentation

Studies were stratified in subgroups according to:

-

1.

type of intervention (e.g., aerobic exercise, range of motion (ROM) exercise, strength exercise, and balance exercise),

-

2.

duration of follow-up (e.g., at the end of treatment and 3, 6, and 12 months after treatment) and

-

3.

primary outcome measures, such as pain and physical function.

In each group, the analysis was divided into aquatic exercise versus nonexercise, or aquatic exercise versus another active type of exercise.

Meta-analysis focused on outcome measures concerning improvement in the following aspects: pain, physical function, stiffness, QOL, and mental health.

Data extraction

Two authors (Yanan Li and Yiru Wang) independently extracted data on study characteristics, such as participants, interventions, cointerventions, control conditions, outcome measures, and results. Uncertainty or disagreement was resolved by discussion with a third author (Ziyi Zhang).

When choosing outcome measures for analysis, we decided on the following priority lists if more than one measured parameter in a category was present in the study:

-

The list of pain measures was as follows (in descending order): visual analog scale (VAS pain), Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC pain), Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS pain), Short Form-36 (SF-36 pain), Short Form-12 (SF-12 pain), and Arthritis Impact Measurement Scale (AIMS pain).

-

The list of physical function measures was as follows (in descending order): WOMAC function, Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ function), KOOS activities of daily living (ADL), SF-36 physical function, and Arthritis Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (ASEQ function).

-

The list of stiffness measures was as follows (in descending order): WOMAC stiffness, ROM, and KOOS stiffness.

-

The list of QOL measures was as follows (in descending order): SF-36 QOL, KOOS QOL, AIMS-2 affect, and Quality of Well-Being Scale (QWB).

-

The list of mental health measures was as follows (in descending order): SF-36 mental, SF-12 mental, AIMS-2 satisfaction, and ASEQ mental.

Measures of treatment effect

If at least two trials of comparable aquatic exercise protocols and outcome measures existed, meta-analysis was conducted using Review Manager 5.1 software (The Cochrane Collaboration, Software Update, Oxford) [24]. Standardized mean differences (SMD) with 95 % confidence intervals (CI) were calculated to assess intervention effects. Judgment of overall effect size was based on Cohen’s categories: SMD of 0.2–0.5 was considered a small effect, SMD of 0.5–0.8 a moderate effect, and SMD > 0.8 a large effect [25].

Grades of evidence were judged using criteria from the Cochrane Back Review Group as follows [26]: Strong evidence: consistent findings among multiple RCTs with low risk of bias; moderate evidence: consistent findings among multiple high-risk RCTs and/or one low-risk RCT; limited evidence: one RCT with high risk of bias; conflicting evidence: inconsistent findings among multiple RCTs; or no evidence: no RCTs.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Statistical heterogeneity between studies was tested by performing a χ-squared test. I2 > 25 %, I2 > 50 %, and I2 > 75 % were defined to indicate moderate, substantial, and considerable heterogeneity, respectively [23]. If the P-value of this test was < 0.1, an I2 test was performed. If the I2 test showed a value > 50 %, we considered this to indicate substantial heterogeneity and a random effects model was performed.

Results

Study selection

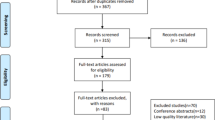

A total of 1048 papers were identified from the database searches, 255 of which were duplicates (Fig. 1). Of the remaining 793 papers, 760 were excluded based on title or abstract; therefore, 33 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility [8, 11, 13, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56]. Twenty-seven full-text articles were excluded because they involved mixed patient samples [8, 13, 33, 44, 46, 48, 49], were not RCTs [27, 28, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 55], had no clinical outcomes [31, 42, 53], did not involve exercise (only water immersion) [32, 39, 41, 47, 51, 52, 54], or were only a protocol [29] or abstract [34]. Six studies involving 398 participants were included in qualitative and quantitative analyses [11, 36, 37, 38, 43, 56].

Study characteristics

Characteristics of the included studies, including samples, interventions, outcome measures, and results, are presented in Tab. 1.

Setting and participant characteristics

Trials originated from the United States [56], Denmark [43], Taiwan [36], Brazil [11], Thailand [38], and Korea [37]. Patients were recruited from outpatient clinics [11, 37, 38, 43, 56] or local community centers [36]. Subjects were diagnosed according to criteria of the American College of Rheumatology (ARC) [11, 43] with clinical [11] and radiographic [11, 36, 37] confirmation of primary [38, 43] and moderate [38, 56] knee OA. In one study, knee pain ranging from 30 to 90 mm on a VAS [11] was also an inclusion criterion. Patients were excluded if they underwent arthroscopic surgery within 1 year [38], had inflammatory joint disease [37, 43, 56], had skin disease [11, 37], received knee joint replacement [36, 43], had received intra-articular corticosteroid injection in the past 30 days [36] or 3 months [11, 38], practiced regular physical activity [11, 36], or had received physical therapy intervention for their knee in the preceding 3 [38] or 6 months [11].

On average, patients were aged in their 60s or 70s, and the majority were female. Two studies reported adverse events [36, 43]. Data on ethnicity were available in two studies [36, 43].

Intervention characteristics

Aquatic exercise lasted 6 [38, 56], 8 [37, 43], 12 [36], or 18 weeks [11], with sessions offered two- [43] or three-times [11, 36, 37, 56] per week. Aquatic exercise included stretching [11, 38, 43], fast walking [37, 38], strengthening [11, 37, 43], and/or aerobic training [36, 37].

Control interventions included land-based exercise [11, 36, 37, 38, 43, 56], following treatment as usual [37], or home-based exercise [36].

Patients received nonsteroidal inflammatory drugs as a cointervention in two studies [11, 38].

Outcome measures

Pain was assessed in five studies; four used a VAS [11, 38, 43, 56] and one used the KOOS pain scale [36]. Physical function was assessed in three studies; two used the KOOS ADL scale [36, 43] and one used the WOMAC function scale. Stiffness was assessed in three studies; two used ROM and one used the WOMAC stiffness scale. Three studies measured QOL using the KOOS QOL scale [36, 38, 43].

Risk of bias in included studies

All studies had a high risk of bias due to nonblinding of participants (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3). All studies had a low risk of reporting bias and attrition bias. All studies also had a low risk of detection bias, with only Yennan et al. [38] not reporting further details regarding assessor blinding. The risk of selection bias was mixed; only one study reported allocation concealment [43] and four studies conducted random sequence generation [11, 36, 37, 43].

Effect of interventions

Aquatic exercise vs. land-based exercise: measurements immediately after exercise intervention

Meta-analysis revealed there was no significant effect on physical function (SMD 0.31; 95 % CI − 0.01–0.63), pain intensity (SMD − 0.25; 95 % CI − 0.74–0.24), stiffness (SMD − 0.15; 95 % CI − 0.47–0.17), or QOL (SMD 0.26; 95 % CI − 0.05–0.58) in favor of aquatic exercise immediately after the intervention (Fig. 4). Only one study reported mental health measurement and there was no evidence for an effect [37].

Aquatic exercise vs. land-based exercise: follow-up measurements

Only one study reported 3 months of follow-up measurements [43]. No evidence for physical function or QOL was found for aquatic exercise after 3 months of treatment. There was limited evidence for pain improvement based on follow-up measurements for land-based exercise when compared with aquatic exercise.

Aquatic exercise vs. nonexercise: measurements immediately after exercise intervention

There was moderate evidence for a moderate effect on physical function (SMD − 0.55; 95 % CI − 0.94 to − 0.16) in favor of aquatic exercise immediately after the intervention. No significant effect was found for pain (SMD − 1.16; 95 % CI − 3.03–0.71) or QOL (SMD − 0.21; 95 % CI − 0.59–0.18; Fig. 4). No evidence was found for stiffness [36] or mental health [37].

Aquatic exercise vs. nonexercise: follow-up measurements

Only one study reported 3 months of follow-up measurements [43]. No evidence for physical function or QOL was found for aquatic exercise after 3 months of treatment. There was limited evidence for pain improvement based on follow-up measurements for aquatic exercise when compared with nonexercise strategies.

Discussion

The purpose of this review was to evaluate the curative efficacy of aquatic exercise in patients with knee OA. Knee OA is more prevalent in the elderly, and is associated with large societal and economic burdens. According to previous reports, elderly Chinese women have a higher prevalence of knee OA than Caucasian women [57, 58]. Interventions for knee OA that can stop or slow disease progression are of great importance—from both economic and patient QOL-related viewpoints.

Because of the intervention properties of aquatic exercise, blinding of subjects and executors is impossible. The awareness of being treated may provide a bias when compared to a control group not exposed to treatment. Since both aquatic and land-based exercises in this review involved active treatment and attention from executors, one must assume there is no such bias effect. We identified all studies with a high risk of performance bias (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3) and found very few high-quality studies acceptable for meta-analysis. Furthermore, descriptions of adverse events and withdrawals were generally insufficient. All studies had more than 80 % attendance, however, which is very good for a therapy that demands out-of-house treatment several times a week.

At the end of treatment, meta-analysis revealed there was no significant difference in effects on physical function, pain intensity, stiffness, or QOL between aquatic and land-based exercises immediately after the interventions. The same observation was made for physical function and QOL based on follow-up measurements in one included study; however, pain improvement was superior with land-based exercise compared with aquatic exercise [43].

Aquatic exercise appears to have considerable short-term benefits compared with land-based exercise in patients with knee OA.

Our data are consistent with findings from another systematic review of RCTs of aquatic exercise for hip or knee OA, which was performed to identify function, mobility, and other health outcomes [14].

There was moderate evidence of a moderate effect on physical function (SMD − 0.55; 95 % CI − 0.94 to − 0.16) in favor of aquatic exercise immediately after the intervention, when comparing aquatic exercise with nonexercise [36, 43]. This result is consistent with findings from a previous systematic review [16]. We conducted a further meta-analysis between land-based exercise and nonexercise and their effect on physical function, and determined there was no significant effect (Fig. 4).

Based on these results, physicians may consider advising patients with knee OA to choose aquatic exercise to help maintain function.

When patients are unable to exercise on land, or find land-based exercise difficult, aquatic programs provide an enabling alternative strategy, especially in patients with greater disability. On the other hand, exercise on land may be arranged more easily and at a lower cost.

There was no evidence for stiffness, QOL, or mental health with aquatic exercise. The same observation was made for pain improvement with aquatic exercise immediately after the intervention when comparing aquatic exercise with nonexercise [36, 43]. This finding is different from two studies included in this review [11, 56], which reported aquatic exercise was better for pain reduction when compared with land-based exercise immediately after the interventions. The different pain measures used in these studies may partially explain the different results; a VAS was used to measure pain in the latter two studies. It is possible that the VAS was more sensitive to changes compared with the pain dimension of the KOOS or WOMAC. This may be seen in one study included in this review [43], which found no group differences in the pain dimension of the KOOS. Therefore, we suggest that future studies should use a VAS for pain measurement.

The effects on physical function did not last up to a 3-month follow-up according to the only study that reported such follow-up measurements [43]. There was limited evidence for pain improvement with aquatic exercise when comparing aquatic exercise with nonexercise. In addition, no evidence was found for physical function or QOL. Studies with long-term outcomes are necessary to determine further use of this therapy.

There is a lack of information on patient satisfaction and adherence to the exercise intervention, despite the importance of patient engagement in exercise programs. One potential limitation of the present meta-analysis is the relatively small number of included studies, which makes it difficult to draw firm conclusions. A second limitation is the substantial heterogeneity and variety of exercise strategies among studies. A third limitation is whether the positive effects of aquatic exercise might only be temporary. We are unable to clarify this issue, since the longest follow-up was only 3 months and was reported in only one study [43].

Conclusion

Overall, aquatic and land-based exercises appear to result in comparable benefits for participants. Meta-analysis did not provide confidence that either aquatic or land-based exercise provides greater improvements in physical function, QOL, or pain. Variability in study parameters, study quality, and exercise strategies may have confounded perception of the effects. Meanwhile, aquatic exercise has some short-term benefits compared with nonexercise. Studies in this area are still too few to provide further recommendations on how to apply this therapy. More research is required to determine if the positive effects of aquatic exercise can be supported by appropriately designed studies with medium- and long-term follow-ups.

References

Sabatini M, Pastoureau P, De Ceuninck F (2004) Cartilage and Osteoarthritis. 1st edn. Humana Pr Inc, Totowa, pp 1–2

Dawson J, Linsell L, Zondervan K et al (2004) Epidemiology of hip and knee pain and its impact on overall health status in older adults. Rheumatology (Oxford) 43(4):497–504

Baker K, McAlindon T (2000) Exercise for knee osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 12(5):456–463

Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D et al (2014) The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 73(7):1323–1330

American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons: treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: evidence-based guideline, 2nd edn. http://www.aaos.org/research/guidelines/Treatment of Osteoarthritis of the Knee Guideline.pdf. Accessed 18 July 2013

Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G et al (2008) OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, Part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 16(2):137–162

Misso ML, Pitt VJ, Jones KM et al (2008) Quality and consistency of clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis and management of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: a descriptive overview of published guidelines. Med J Aust 189(7):394–399

Foley A, Halbert J, Hewitt T, Crotty M (2003) Does hydrotherapy improve strength and physical function in patients with osteoarthritis – a randomised controlled trial comparing a gym based and a hydrotherapy based strengthening programme. Ann Rheum Dis 62(12):1162–1167

Harrison R, Bulstrode S (1987) Percentage weight-bearing during partial immersion. Physiotherapy Practical 3:60–63

Campion MR (1997) Hydrotherapy: principles and practice, 2nd edn. Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford

Silva LE, Valim V, Pessanha AP et al (2008) Hydrotherapy versus conventional land-based exercise for the management of patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized clinical trial. Physical Therapy 88(1):12–21

Kargarfard M, Etemadifar M, Baker P et al (2012) Effect of aquatic exercise training on fatigue and health-related quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 93(10):1701–1708

Cadmus L, Patrick MB, Maciejewski ML et al (2010) Community-based aquatic exercise and quality of life in persons with osteoarthritis. Med Sci Sports Exerc 42(1):8–15

Batterham SI, Heywood S, Keating JL (2011) Systematic review and meta-analysis comparing land and aquatic exercise for people with hip or knee arthritis on function, mobility and other health outcomes. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 12:123

Rahmann AE (2010) Exercise for people with hip or knee osteoarthritis: a comparison of land-based and aquatic interventions. Open Access J Sports Med 1:123–135

Bartels EM, Lund H, Hagen KB et al (2007) Aquatic exercise for the treatment of knee and hip osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4:CD005523

Hall J, Swinkels A, Briddon J, McCabe CS (2008) Does aquatic exercise relieve pain in adults with neurologic or musculoskeletal disease? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 89(5):873–883

Kamioka H, Tsutani K, Mutoh Y et al (2011) A systematic review of nonrandomized controlled trials on the curative effects of aquatic exercise. Int J Gen Med 4:239–260

McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC et al (2014) OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 22(3):363–388

Belo JN, Berger MY, Koes BW, Bierma-Zeinstra SM (2009) The prognostic value of the clinical ACR classification criteria of knee osteoarthritis for persisting knee complaints and increase of disability in general practice. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 17(10):1288–1292

Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D et al (1986) Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis Rheum 29(8):1039–1049

Bellamy N, Kirwan J, Boers M et al (1997) Recommendations for a core set of outcome measures for future phase III clinical trials in knee, hip, and hand osteoarthritis. Consensus development at OMERACT III. J Rheumatol 24(4):799–802

Higgins JPT, Green S (eds) (2011) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration. http://www.cochrane-handbook.org

Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.1. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. 2011

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral health sciences, 2nd edn. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., Hillsdale

Furlan AD, Pennick V, Bombardier C, Tulder M van (2009) 2009 updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Back Review Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 34(18):1929–1941

Lau MC, Lam JK, Siu E et al (2014) Physiotherapist-designed aquatic exercise programme for community-dwelling elders with osteoarthritis of the knee: a Hong Kong pilot study. Hong Kong Med J 20(1):16–23

Fernandes Guerreiro JP, Turin Claro RF, Rodrigues JD, Alvarenga Freire BF (2014) Effect of watergym in knee osteoathritis. Acta Ortopedica Brasileira 22(1):25–28

Yazigi F, Espanha M, Vieira F et al (2013) The PICO project: aquatic exercise for knee osteoarthritis in overweight and obese individuals. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 14:320

Roper JA, Bressel E, Tillman MD (2013) Acute aquatic treadmill exercise improves gait and pain in people with knee osteoarthritis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 94(3):419–425

Chaparro G, Lievense C, Gabay L et al (2013) Comparison of balance outcomes between aquatic and land-based exercises in older adults with knee osteoarthritis. Med Sci Sports Exerc 451(5):289

Fioravanti A, Giannitti C, Bellisai B et al (2012) Efficacy of balneotherapy on pain, function and quality of life in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Int J Biometeorol 56(4):583–590

Hale LA, Waters D, Herbison P (2012) A randomized controlled trial to investigate the effects of water-based exercise to improve falls risk and physical function in older adults with lower-extremity osteoarthritis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 93(1):27–34

Kaya E, Ozyurek S, Oguzhan H (2011) The effect of balneotherapy and mud pack treatment in knee osteoarthritis. Eur J Pain Suppl 5S(1):282

Slivar SR, Peri D, Jukic I (2011) The relevance of muscle strength – extensors of the knee on pain relief in elderly people with knee osteoarthritis. Reumatizam 58(1):21–26

Wang TJ, Lee SC, Liang SY et al (2011) Comparing the efficacy of aquatic exercises and land-based exercises for patients with knee osteoarthritis. J Clin Nurs 20(17–18):2609–2622

Lim JY, Tchai E, Jang SN (2010) Effectiveness of aquatic exercise for obese patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. PM R 2(8):723–731, 793

Yennan P, Suputtitada A, Yuktanandana P (2010) Effects of aquatic exercise and land-based exercise on postural sway in elderly with knee osteoarthritis. Asian Biomedicine 4(5):739–745

Forestier R, Desfour H, Tessier JM et al (2010) Spa therapy in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a large randomised multicentre trial. Ann Rheum Dis 69(4):660–665

Kilicoglu O, Donmez A, Karagulle Z et al (2010) Effect of balneotherapy on temporospatial gait characteristics of patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Rheumatol Int 30(6):739–747

Fioravanti A, Iacoponi F, Bellisai B et al (2010) Short- and long-term effects of spa therapy in knee osteoarthritis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 89(2):125–132

Handa S, Kamijo Y, Yamazaki T et al (2009) The effects of high-intensity interval walking training with water immersion in middle-aged and older women with light knee osteoarthritis. J Physiol Sci 59S(1):356

Lund H, Weile U, Christensen R et al (2008) A randomized controlled trial of aquatic and land-based exercise in patients with knee osteoarthritis. J Rehabil Med 40(2):137–144

Cadmus L, Patrick MB, Maciejewski ML et al (2008) Aquatic exercise and quality of life in persons with osteoarthritis. Am J Epidemiol 167S(11):S6

Fukusaki C, Nakazawa K (2008) Acute effects of aquatic exercise on postural control in patients with lower extremity arthritis. Jpn J Phys Fitness Sports Med 57(3):377–382

Fransen M, Nairn L, Winstanley J et al (2007) Physical activity for osteoarthritis management: a randomized controlled clinical trial evaluating hydrotherapy or Tai Chi classes. Arthritis Rheum 57(3):407–414

Evcik D, Kavuncu V, Yeter A, Yigit I (2007) The efficacy of balneotherapy and mud-pack therapy in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Joint Bone Spine 74(1):60–65

Wang T, Belza B, Thompson FE et al (2007) Effects of aquatic exercise on flexibility, strength and aerobic fitness in adults with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Adv Nurs 57(2):141–152

Hinman RS, Heywood SE, Day AR (2007) Aquatic physical therapy for hip and knee osteoarthritis: Results of a single-blind randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther 87(1):32–43

Lee HY (2006) Comparison of effects among Tai-Chi exercise, aquatic exercise, and a self-help program for patients with knee osteoarthritis. Taehan Kanho Hakhoe Chi 36(3):571–580

Yurtkuran M, Yurtkuran M, Alp A et al (2006) Balneotherapy and tap water therapy in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Rheumatol Int 27(1):19–27

Cusack T, McAteer MF, Daly LE, McCarthy CJ (2005) Knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial comparing hydrotherapy and continuous short-wave diathermy. Arthritis Rheum 52S(9):S506

Silva LE, Pessanha AC, Oliveira LM et al (2005) Efficacy of water exercise in the treatment of patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized, single-blind, controlled clinical trial. Annals Of The Rheumatic Diseases 64S(3):556

Tishler M, Rosenberg O, Levy O et al (2004) The effect of balneotherapy on osteoarthritis. Is an intermittent regimen effective? Eur J Intern Med 15(2):93–96

Patrick M, Patrick D, Maciejewski M et al (2004) How does aquatic exercise affect quality of life in persons with osteoarthritis? Arthritis Rheum 50S(9):S469

Wyatt FB, Milam S, Manske RC, Deere R (2001) The effects of aquatic and traditional exercise programs on persons with knee osteoarthritis. J Strength Cond Res 15(3):337–340

Zhang Y, Xu L, Nevitt MC et al (2001) Comparison of the prevalence of knee osteoarthritis between the elderly Chinese population in Beijing and whites in the United States: The Beijing Osteoarthritis Study. Arthritis Rheum 44(9):2065–2071

Xu L, Nevitt MC, Zhang Y et al (2003) High prevalence of knee, but not hip or hand osteoarthritis in Beijing elders: comparison with data of Caucasian in United States. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 83(14):1206–1209

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Conflict of interest. Meili Lu, Youxin Su, Yingjie Zhang, Ziyi Zhang, Wenting Wang, Zhen He, Feiwen Liu, Yanan Li, Changyan Liu, Yiru Wang, Lu Sheng, Zhengxuan Zhan, Xu Wang, and Naixi Zheng state that there are no conflicts of interest. The accompanying manuscript does not include studies on humans or animals.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The authors are grateful to the State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine for funding this study (No. 201307004).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, M., Su, Y., Zhang, Y. et al. Effectiveness of aquatic exercise for treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Z Rheumatol 74, 543–552 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00393-014-1559-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00393-014-1559-9