Abstract

Purpose

Primary squamous cell carcinomas of the colon and rectum are extremely rare, with an incidence of less than 1 % of colorectal malignancies. Our aim in this study was to evaluate patient characteristics, treatment strategy, and postoperative follow-up of patients with colorectal squamous cell carcinoma.

Methods

We reviewed our prospectively maintained colorectal cancer database for all patients who were diagnosed with colorectal squamous cell carcinoma between January 1990 and April 2009.

Results

Out of 5149 patients with colorectal malignancy, 11 patients (0.2 %) met the study criteria. Median age at the time of diagnosis was 64. Median BMI was 28 kg/m2. The tumors were localized in the rectum (n = 8), right colon (n = 2), and sigmoid colon (n = 1). The pathologic stages of these tumors were I (n = 1), II (n = 4), III (n = 3), and IV (n = 3). Operations performed were abdominoperineal resection (n = 4), right colectomy (n = 2), total colectomy (n = 1), low anterior resection (n = 1), local excision (n = 1), sigmoidectomy (n=1) and end colostomy creation (n = 1). One patient received intraoperative radiotherapy. Postoperative chemotherapy was given to eight patients, and three patients received postoperative radiation therapy. Median follow-up after diagnosis was 42 months (12–96). Three patients developed recurrence after potentially curative surgery. Five patients died from metastatic disease during follow-up.

Conclusion

Squamous colorectal cancer can be detected in any part of the colon, generally presents at a later stage, and is associated with a poor prognosis. Surgery is the mainstay of treatment. Various adjuvant chemoradiation treatments appear not to influence the outcome. Further cases need to be analyzed in order to find more effective treatment regimens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Primary adenosquamous carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the colon and rectum are extremely rare with a reported incidence of 0.25–0.85 % of all colorectal malignancies [1]. First reported by Herxheimer in 1907, it has been described as a tumor in which both the glandular component and the squamous component are malignant and capable of metastasizing [2, 3]. Recent studies suggest that SCCs of the colon and upper rectum represent a poorly differentiated cancer with squamous characteristics [4]. Adenosquamous and squamous colorectal carcinomas belong to the same entity, and the squamous epithelial components have more invasive power than the glandular components [5, 6].

The largest institutional series is by Nahas et al. and consists of 12 cases [5]; the remainder of the literature consists of case reports from different institutions. It is important to define SCCs of the colon and rectum; therefore, absence of SCC metastasis from other organs to the colon and rectum, absence of anal SCC, and absence of squamous epithelium-lined anorectal fistula must be ruled out [7–9]. The risk factors associated with primary colorectal SCC are not well defined, and data on this entity is limited [6]. Our aim in this study was to evaluate patient characteristics, treatment strategy, and postoperative follow-up of patients with colorectal squamous cell carcinoma.

Patients and methods

After obtaining institutional review board (IRB) approval, patients who were diagnosed with colorectal SCC in our institution from January 1990 to April 2009 were analyzed in the study. Patients with primary colorectal squamous cell carcinoma with the following characteristics: absence of primary squamous cell carcinoma in any other organ, absence of squamous-lined and chronic fistulous tracts, and a distinct demarcation of the tumor from the squamous epithelium of the anal canal were included. Patients’ age, gender, ASA (America Society of Anesthesiologists) classification, presentation, location and stage of tumor, operation performed, oncologic treatment, and follow-up after diagnosis were evaluated. Data of patients were retrieved from the IRB-approved, prospectively maintained cancer database with supplemental information from patient charts. Quantitative data were reported as median (range) and categorical data as numbers.

Results

Out of 5149 patients with colorectal malignancy, 11 patients (8 female) (0.2 %) met the study criteria. Median age at the time of diagnosis was 64 (43–82). Median BMI was 28 (19–47). Ten out of the 11 patients did not receive any immunosuppressive treatment for any reason. One patient was treated for acute myeloid leukemia 30 years before diagnosis of SCC and was in remission. No patients were infected with human immunodeficiency virus. One patient had cervical cauterization due to cervical dysplasia 13 years before diagnosis of SCC. One patient had prior radiotherapy for prostate cancer. One patient received neoadjuvant chemoradiation. Presenting symptoms included change in bowel habits (n = 5), abdominal pain (n = 3), rectal pain (n = 2), anemia (n = 1), obstruction (n = 1), and rectal bleeding (n = 1). The tumors were localized in the rectum (n = 8), right colon (n = 2), and sigmoid colon (n = 1). The lowest distance from the anal verge was 5 cm, the longest distance was 12 cm, and the median distance was 7 cm in patients with rectal SCC. Three out of 11 patients had metastatic disease (stage IV) at the time of diagnosis. One patient had stage I, four patients had stage II, and three patients had stage III diseases. Operations performed were abdominoperineal resection (n = 4), right colectomy (n = 2), subtotal colectomy (n = 1), low anterior resection (n = 1), local excision (n = 1), sigmoidectomy (n=1) and end colostomy creation (n = 1). One patient had adenosquamous cancer; others had SCC. One patient had ulcerative colitis and underwent a subtotal colectomy. One patient received intraoperative radiotherapy due to a tumor extending into her left pelvic sidewall. Three patients had postoperative radiotherapy, and eight patients had chemotherapy postoperatively. The details of the adjuvant treatment and follow-up were summarized in Table 1. Median follow-up after diagnosis was 42 months (12–96). Three patients developed recurrence after potentially curative surgery. Five patients died from metastatic disease during follow-up.

Discussion

The widely accepted criteria for the diagnosis of adenosquamous and SCCs of the colon and rectum are the absence of primary SCC in any other organ, absence of squamous-lined fistulous tracts, and a distinct demarcation of the tumor from the squamous epithelium of the anal canal [7–9]. The pathogenesis of colorectal SCC is not well defined. Various studies have described theories on development of SCC of the colon and rectum, such as differentiation of pluripotent stem cells, cancerous transformation of ectopic embryonic nests originating ectodermal cells, squamous differentiation of a colonic adenoma, or a squamous metaplasia from external irritation [4, 7, 8]. Chronic inflammation due to ulcerative colitis or chronic infection, smoking, human immunodeficiency virus, and HPV [5] are other factors that have been associated with SCC [10, 11]. Overexpression of P16 was found to be associated with high-risk HPV types in cervical lesions or anorectal squamous cell cancers [12, 13]. Cervical cauterization was performed in one of our patients because of cervical dysplasia. However, it has been shown that HPV infection is not associated with colorectal SCC [6]. The majority of patients were female in our series and previous reports [8]. Pain and irregularity in bowel movements were the most common symptoms. Clinical manifestations of SCC are very similar to colonic adenocarcinoma [6]. The majority of the cases with colorectal SCC were located in the rectum [14]. Some rectal SCCs originate from the anal canal and extend in to the distal rectum [14]. However, there are some differences between anal SCC and rectal SCC including cytokeratin staining profile [5] and localization characteristics. Sedgwick and Wainstein reported that 3 % of cases diagnosed with anorectal SCC have confined areas lined by columnar epithelium [15]. In a series of 424 patients with anorectal SCC, Cullen and Mayo found all rectal SCCs between 5 to 24 cm from the anal margin [16].

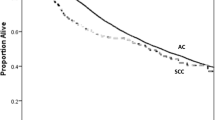

The majority of our patients presented with locally advanced and metastatic disease. Cancer-related mortality was high regardless of the stage of disease at the time of diagnosis. It has been shown that SCC is associated with higher mortality in comparison with adenocarcinoma [17]. Survival in colorectal SCC is poorer than that in adenocarcinomas alone [4, 18]. One patient underwent neoadjuvant chemoradiation followed by radical surgery. A complete response was not seen after neoadjuvant chemoradiation in this patient. Surgery was the mainstay of treatment in patients without metastasis [19]. Various adjuvant chemoradiation treatments appear not to influence the outcome. FU-based regimen is administered in general [8] for colorectal SCC. Some authors used a platinum-based drug as one of the standard regimens for anal SCC at that time [20–22]. A combination of cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil, and leucovorin therapy has also been suggested for patients with metastatic disease [19]. Intraoperative radiotherapy was performed in a patient with a tumor extending into the pelvic sidewall. However, this patient died of recurrent disease.

Chemoradiation has been used as a primary treatment in several patients with nonmetastatic rectal SCC [8, 20]. Based on this clinical practice, surgery is performed if a patient does not want chemoradiation primarily or if there is recurrence or persistence of tumor following chemoradiation. There is no universally accepted chemoradiation regimen for rectal SCC [8]. It may be prudent to treat rectal SCC with similar regimens as anal SCC.

A retrospective design, low patient number, and nonstandard treatment approach were the major limitations of the study. A randomized study evaluating different treatment options for colorectal SCC cannot be performed due to the rarity of this tumor. Testing different therapies with longer follow-up may provide more data. Further investigations using molecular and biologic approaches on a larger number of cases may improve our understanding of this tumor. Our results show that SCC generally presents at an advanced stage and is associated with a poor prognosis. Chemoradiation for colorectal SCC is generally preferred due to its similar features with anal SCC. However, curative surgery with or without chemoradiation still appears as the most reliable treatment alternative when feasible.

References

Kiran RP, Tripodi G, Frederick W, Dudrick SJ (2006) Adenosquamous carcinoma of the colon: a rare tumor. Am Surg 72:754–755

Herxheimer G (1907) Uber heterologe cancroid. Beitr Path Anat 41:348

Birnbaum W (1970) Squamous cell carcinoma and adenoacanthoma of the colon. JAMA 212:1511–1513

Frizelle FA, Hobday KS, Batts KP, Nelson H (2001) Adenosquamous and squamous carcinoma of the colon and upper rectum: a clinical and histopathological study. Dis Colon Rectum 22:341–346

Nahas CS, Shia J, Joseph R, Schrag D, Minsky BD, Weiser MR, Guillem JG, Paty PB, Klimstra DS, Tang LH, Wong WD, Temple LK (2007) Squamous cell carcinoma of the rectum: a rare but curable tumor. Dis Colon Rectum 50:1393–1400

Audeau A, Han HW, Johnston MJ, Whitehead MW, Frizelle FA (2002) Does human papilloma virus have a role in squamous cell carcinoma of the colon and upper rectum? Eur J Surg Oncol 28:657–660

Williams GT, Blackshaw AJ, Morson BC (1979) Squamous carcinoma of the colorectum and its genesis. J Pathol 129:139–147

Yeh J, Hastings J, Rao A, Abbas MA (2012) Squamous cell carcinoma of the rectum: a single institution experience. Tech Coloproctol 16:349–354

Hickey WF, Corson JM (1981) Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a duplication of the colon: case report and literature review of squamous cell carcinoma of the colon and of malignancy complicating colonic duplication. Cancer 47:602–609

Weiner MF, Polayes SH, Yidi R (1962) Squamous carcinoma with schistosomiasis of the colon. Am J Gastroenterol 37:48–54

Pittella JE, Torres AV (1982) Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the cecum and ascending colon: report of a case and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum 25:483–487

Agoff SN, Lin P, Morihara J, Mao C, Kiviat NB, Koutsky LA (2003) p16(INK4a) expression correlates with degree of cervical neoplasia: a comparison with Ki-67 expression and detection of high-risk HPV types. Mod Pathol 16:665–673

Lu DW, El-Mofty SK, Wang HL (2003) Expression of p16, Rb, and p53 proteins in squamous cell carcinomas of the anorectal region harboring human papillomavirus DNA. Mod Pathol 16:692–699

Gaston EA (1967) Squamous-cell carcinoma of the colon and rectum: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum 10:435–442

Sedgwick CE, Wainstein E (1959) Epidermoid carcinoma of the anus and rectum. Surg Clin N Am 39:759

Cullen PK Jr, Mayo CW (1963) A further evaluation of the one-stage low-anterior resection. Dis Colon Rectum 6:415

Masoomi H, Ziogas A, Lin BS, Barleben A, Mills S, Stamos MJ, Zell JA (2012) Population-based evaluation of adenosquamous carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Dis Colon Rectum 55:509–514

Cagir B, Nagy MW, Topham A, Rakinic J, Fry RD (1999) Adenosquamous carcinoma of the colon, rectum, and anus: epidemiology, distribution, and survival characteristics. Dis Colon Rectum 42:258–263

Juturi JV, Francis B, Koontz PW, Wilkes JD (1999) Squamous-cell carcinoma of the colon responsive to combination chemotherapy: report of two cases and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum 42:102–109

Tronconi MC, Carnaghi C, Bignardi M, Doci R, Rimassa L, Di Rocco M, Scorsetti M, Santoro A (2010) Rectal squamous cell carcinoma treated with chemoradiotherapy: report of six cases. Int J ColorDis 25:1435–1439

Doci R, Zucali R, La Monica G, Meroni E, Kenda R, Eboli M, Lozza L (1996) Primary chemoradiation therapy with fluorouracil and cisplatin for cancer of the anus: results in 35 consecutive patients. J Clin Oncol 14:3121–3125

Bartelink H, Roelofsen F, Eschwege F, Rougier P, Bossett JF, Gonzalez DG, Peiffert D, van Glabbeke M, Pierart M (1997) Concomitant radiotherapy and chemotherapy is superior to radiotherapy alone in the treatment of locally advanced anal cancer: results of a phase III randomized trial of the European organization for research and treatment of cancer radiotherapy and gastrointestinal cooperative groups. J Clin Oncol 15:2040–2049

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Ed and Joey Story Endowed Chair in Colorectal Surgery.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ozuner, G., Aytac, E., Gorgun, E. et al. Colorectal squamous cell carcinoma: a rare tumor with poor prognosis. Int J Colorectal Dis 30, 127–130 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-014-2058-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-014-2058-9