Abstract

To gain better understanding of the diversity and evolution of the gene regulation system in eukaryotes, the phosphate signal transduction (PHO) pathway in non-conventional yeasts has been studied in recent years. Here we characterized the PHO pathway of Hansenula polymorpha, which is genetically tractable and distantly related to Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe, in order to get more information for the diversity and evolution of the PHO pathway in yeasts. We generated several pho gene-deficient mutants based on the annotated draft genome of H. polymorpha BY4329. Except for the Hppho2-deficient mutant, these mutants exhibited the same phenotype of repressible acid phosphatase (APase) production as their S. cerevisiae counterparts. Subsequently, Hppho80 and Hppho85 mutants were isolated as suppressors of the Hppho81 mutation and Hppho4 was isolated from Hppho80 and Hppho85 mutants as the sole suppressor of the Hppho80 and Hppho85 mutations. To gain more complete delineation of the PHO pathway in H. polymorpha, we screened for UV-irradiated mutants that expressed APase constitutively. As a result, three classes of recessive constitutive mutations and one dominant constitutive mutation were isolated. Genetic analysis showed that one group of recessive constitutive mutations was allelic to HpPHO80 and that the dominant mutation occurred in the HpPHO81 gene. Epistasis analysis between Hppho81 and the other two classes of recessive constitutive mutations suggested that the corresponding new genes, named PHO51 and PHO53, function upstream of HpPHO81 in the PHO pathway. Taking these findings together, we conclude that the main components of the PHO pathway identified in S. cerevisiae are conserved in the methylotrophic yeast H. polymorpha, even though these organisms separated from each other before duplication of the whole genome. This finding is useful information for the study of evolution of the PHO regulatory system in yeasts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

To adapt to environmental changes and survive in various conditions, microorganisms have evolved complex pathways of signal transduction. A phosphate-responsive signaling pathway, known as the PHO pathway, regulates the genes required to maintain proper phosphate homeostasis in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae and is the best-studied example of phosphate homeostasis in eukaryotes (reviewed in Ljungdahl and Daignan-Fornier 2012; Oshima 1997; Yadav et al. 2015). Because inorganic phosphate (Pi) is an essential nutrient for all organisms, it is thought that the PHO pathway is likely to be conserved in other eukaryotes at least to some extent and to be a good model system for studying the diversity and evolution of the regulatory system in eukaryotes. In S. cerevisiae, under the condition of high extracellular phosphate, the transcriptional activator Pho4 is phosphorylated by the cyclin-dependent kinase–cyclin (CDK–cyclin) complex Pho85–Pho80, transported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm by Msn5, and prevented from interaction with the transcription factor Pho2. As a result, phosphate-repressed genes, such as PHO5 and PHO84, are not expressed under this condition. When the extracellular phosphate concentration is sufficiently low, by contrast, the CDK inhibitor (CKI) Pho81, which is activated by inositol heptakisphosphate (IP7, synthesized by Vip1), inhibits the activity of the Pho85–Pho80 complex, enabling Pho4 to localize in the nucleus and induce the expression of phosphate-repressed genes in collaboration with Pho2 (Kaffman et al. 1994, 1998a, b; Lee et al. 2007; Ogawa et al. 1995; Schneider et al. 1994). Recently, Pho92 containing a YTH domain has been reported to regulate PHO4 mRNA stability and to be involved in phosphate and glucose metabolisms (Kang et al. 2014). Although many components of the PHO pathway have been well characterized, the molecular mechanism underlying phosphate sensing remains unclear.

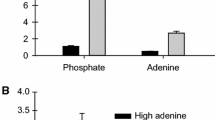

Recently, the PHO pathway has been studied in non-conventional yeasts in order to gain better understanding of the diversity and evolution of the gene regulation system in eukaryotes. For example, many regulatory components of the PHO pathway are conserved in Candida glabrata, although CgPHO2 is not required for transcriptional induction of the phosphate starvation genes (Kerwin and Wykoff 2009). Candida glabrata has also lost the gene PHO5, which encodes a phosphate-repressible acid phosphatase (APase), and instead has evolved the gene CgPMU2, which encodes a broad-range phosphate starvation-regulated acid phosphatase that functionally replaces PHO5 (Orkwis et al. 2010). On the other hand, the PHO pathway of the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe includes no genes orthologous to ScPHO81, ScPHO2 and ScPHO4, and its orthologs of ScPHO80 and ScPHO85 are not involved in the PHO pathway. In addition, the SpPho7 transcriptional activator for the APase gene (Sppho1) is a zinc-finger-type activator that differs from the helix–loop–helix type of the ScPho4 activator (Henry et al. 2011). Moreover, this S. pombe PHO pathway is cross-regulated at the SpPho7 site by phosphate and adenine (Estill et al. 2015).

The PHO pathway has also been studied in the filamentous fungi Neurospora crassa and Aspergillus nidulans since the 1960s. The PHO pathway of N. crassa is known to comprise the genes nuc-1, preg, pgov and nuc-2, which correspond to ScPHO4, ScPHO80, ScPHO85 and ScPHO81, respectively (Kang and Metzenberg 1990; Littlewood et al. 1975; Toh-e and Ishikawa 1971). In A. nidulans, by contrast, the genes that are homologous to ScPHO80 and ScPHO4 are involved in the PHO pathway, but those homologous to ScPHO81 and ScPHO85 are not (Wu et al. 2004). In addition, a recent study on the PHO system of Cryptococcus neoformans reported that CnPHO4, CnPHO80, CnPHO85 and CnPHO81 are PHO regulatory genes (Toh-e et al. 2015). Thus, the cyclin–CDK–CKI complex of core regulatory components in the PHO pathway is not always conserved, although the PHO pathway itself is conserved, even in fungi that are evolutionarily distantly related to S. cerevisiae.

The methylotrophic yeast H. polymorpha is genetically tractable and phylogenetically positioned between S. cerevisiae and the fission yeast S. pombe or filamentous fungi (Dujon 2010; Dujon et al. 2004). It diverged from a common ancestor with S. cerevisiae about a billion years ago, and did not undergo whole-genome duplication. To our knowledge, there have been no studies on its PHO pathway, although HpPHO1 was identified to encode an APase more than 10 years ago (Phongdara et al. 1998). Here, we report characterization of the PHO pathway in H. polymorpha. Using a combination of comparative genomic analysis and classic genetics, we confirm that the PHO pathway consists of HpPHO81, HpPHO80, HpPHO85 and HpPHO4 genes. The genetic roles and positions of these genes in the PHO system are the same as the corresponding genes of S. cerevisiae. In addition, mutants exhibiting constitutive APase expression (termed the PhoC phenotype) were isolated and classified into four groups comprising three groups of recessive mutations and one group of dominant mutations. One of the three recessive PhoC mutations was found to be allelic to Hppho80, whereas the dominant mutation was allelic to HpPHO81. Epistasis analysis of the remaining two groups of recessive mutations with the Hppho81 mutation indicated that the two corresponding genes both function upstream of HpPHO81 in the PHO pathway. We conclude that the main components of the PHO pathway are conserved in H. polymorpha, although this yeast separated from S. cerevisiae before duplication of the whole genome.

Materials and methods

Strains, plasmids and media

The yeast strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Strain BY4329 was used as the wild-type strain for isolation of APase mutants. Strain NY-1 was used for isolation of suppressors of Hppho81 mutation. H. polymorpha gene disruptants were constructed by using a zeocin- or hygromycin-resistance gene, or HpURA3 cassette. Disruption of genes was confirmed by PCR. To construct plasmids YZ3 and YZ6, the HpPHO81 ORF and ScPHO81 ORF were first amplified by PCR and then inserted into plasmid BYP7151 digested by BamHI and HindIII, respectively, via an In-Fusion Cloning kit (Takara Bio Inc., Japan). To construct plasmid YZ14, the HpPHO4 ORF plus 500-bp upstream and 300-bp downstream sequences was amplified by PCR, and inserted into the SmaI restriction site of pFL26. The HpPHO80- and HpPHO85-expression plasmids (YZ77 and YZ78, respectively) were constructed in the same way. For sequence analysis of HpPHO81 C alleles, each HpPHO81 C allele was amplified by PCR and cloned into the BamHI–HindIII gap of pUC19. The PCR primers used to generate strains and plasmids are shown in Table S1.

Yeast strains were grown in nutrient medium containing 200 mg/l of adenine (YPAD), synthetic dextrose medium (SD), or minimal high-Pi and low-Pi media supplemented with appropriate amino acids when needed (Sherman 1991; Toh-e et al. 1973). Mating and sporulation of H. polymorpha were induced on 2.5 % maltose and 0.5 % malt extract medium (MAME) plates at 30 °C. For drug resistance selection, the plates were supplemented with hygromycin B (150 µg/ml, Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd., Japan) or Zeocin™ (100 µg/ml, Invitrogen Corp., USA). E. coli DH5α was cultured in LB broth (Miller 1972) and used for plasmid DNA preparation. For solid media, 2 % agar was added. The growth temperature for yeast and bacteria was 37 °C unless stated otherwise.

Genetic analysis and transformation

Diploid cells were constructed by crossing strains that had auxotrophic mutations complementary to each other on MAME plates. After incubation at 30 °C for 1 day, the mating culture was transferred to an SD plate, and only diploid cells were selected as a prototrophic culture. For sporulation, the resulting diploid cells were incubated on a new MAME plate for 2 days at 30 °C. Tetrads were dissected by a SporePlay™ micromanipulator (Singer Instruments Co. Ltd., UK). Yeast transformation was performed with a Frozen-EZ Yeast Transformation II kit (Zymo Research Inc., USA). For E. coli transformation, ECOS™ Competent E. coli DH5α (Nippon Gene Co. Ltd., Japan) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Genome sequencing and gene annotation

The draft genome sequence of BY4329 was determined and submitted to the DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ), as described by Maekawa and Kaneko (2014). Its BioProject ID is PRJDB3035. Predicted CDS data of the draft genome sequence were obtained by using In Silico Molecular Cloning (IMC) version 5.1 (in silico Biology Inc., Japan) and query amino acid sequences from three yeast amino acid databases (S. cerevisiae, Ogataea parapolymorpha and S. pombe). Gene annotation was carried out by using the BLASTX program within the NCBI nr database and the predicted CDS data as queries. Annotated orthologs of components of the PHO pathway signaling were picked up and their homology to the corresponding S. cerevisiae PHO genes was reconfirmed on the basis of sequence similarity by using the BLASTP feature in the Saccharomyces Genome Database (http://www.yeastgenome.org/).

Isolation of APase mutants

An overnight culture was diluted 10,000-fold with sterile water and 0.1 ml of the diluted culture was spread on a YPAD plate. Cells on the plate were irradiated with ultraviolet (20 or 25 J/m2) by using a Spectrolinker (TOMY Seiko Co. Ltd., Japan). The plates were then incubated at 28 °C for 2 days. Colonies that appeared on the plates were examined for APase production by the colony staining method (Toh-e et al. 1973). Random integration of linear DNA fragments (van Dijk et al. 2001) was also used to obtain APase mutants of H. polymorpha. In brief, the plasmid pREMI-Z (a gift from Y. Sakai) was linearized with BamHI and introduced into H. polymorpha cells. The resultant transformants were selected as zeocin-resistant colonies and their APase phenotype was examined by a colony staining assay. The locus of pREMI-Z insertion was determined by sequencing the plasmid recovered from each transformant.

Assay of APase activity

APase activity was measured by using intact cells, as described previously (Toh-e et al. 1973). One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme liberating 1 µmol of p-nitrophenol in 1 min at 35 °C.

Quantitative reverse-transcription PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated as previously described (van Zutphen et al. 2010), treated with DNase I, and further purified using the RNeasy® Plus Mini Kit (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, Germany). A total of 1 µg RNA was used to synthesize cDNA with SuperScript® III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen™, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and 1 µl cDNA reaction mixture was used in a quantitative PCR reaction with the primers listed in Table S1. PCR products were measured with TaqMan® MGB Gene Expression Kits (Applied Biosystems™, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) using StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems™). Data were normalized to expression of HpACT1.

Results

Gene conservation of the PHO pathway in H. polymorpha

On the basis of the annotated draft genome sequence of BY4329 (Maekawa and Kaneko 2014), we identified genes homologous to regulatory components of the S. cerevisiae PHO pathway in H. polymorpha (Table 2). BLASTP alignment was used to estimate amino acid identity between the homologous genes. We found clear orthologs of ScPHO regulatory components in H. polymorpha—namely, acid phosphatase (encoded by HpPHO1), CKI (HpPHO81), Pho85–cyclin (HpPHO80), CDK (HpPHO85), transcription factor (HpPHO4), and transcription activator (HpPHO2)—as well as genes involved in inositol pyrophosphate synthesis. Therefore, the genomic sequence of H. polymorpha predicts a signaling architecture in the PHO pathway of this organism similar to that of S. cerevisiae. In addition, HpPho1 showed 95 % identity to the previously reported Pho1 of H. polymorpha (ATCC34438; Phongdara et al. 1998).

The least conserved component between the two yeasts was found to be the transcription factor Pho4. Similar to CgPho4, the most conserved portion of HpPho4 is the C-terminal DNA-binding domain (Fig. S1). Kerwin and Wykoff (2010) reported that CgPho4 induces phosphatase activity independent of CgPho2, probably due to its increased size. Thus, we considered that HpPho4 might possibly be able to drive expression of the PHO promoters in the absence of HpPho2.

The core regulatory system of the PHO pathway consists of four components encoded by PHO4, PHO80, PHO81 and PHO85 (Ljungdahl and Daignan-Fornier 2012). In the following work, therefore, we focused on the respective homologs of H. polymorpha to determine whether these four genes play the same roles in the PHO pathway as the S. cerevisiae genes.

HpPHO81 is a CDK inhibitor

First, HpPHO81 was disrupted by insertion of an HpURA3 fragment. The resulting disruptant showed defective APase production and no derepression of PHO1 mRNA level under the low-Pi condition (Table 3), which is the same phenotype as observed for disruption of ScPHO81. This result indicates that HpPHO81 is a positive regulator of the PHO pathway at the transcriptional level in H. polymorpha.

To determine whether HpPHO81 function could replace ScPHO81 function, we constructed an HpPHO81 expression plasmid (YZ3) for S. cerevisiae, and transformed it into the S. cerevisiae strain BY22357 (Scpho81∆). The transformant was pre-cultivated in high-Pi medium and inoculated into high-Pi and low-Pi media at an initial OD660 of 0.1. APase activity was measured after 23 h of cultivation. As shown in Table 4, the HpPHO81 gene complemented the defective APase phenotype of the Scpho81∆ mutant to a level similar to that of the ScPHO81 gene, indicating that HpPho81 is a CDK inhibitor. This finding also suggested that a cyclin–CDK complex might function in the PHO pathway of H. polymorpha.

HpPHO80 and HpPHO85 are involved in the regulation of APase expression

Deletion of either HpPHO80 or HpPHO85 resulted in the PhoC phenotype (Table 3), which is the same phenotype observed after deletion of these genes in S. cerevisiae. Because pho80 and pho85 mutations are known to be epistatic to pho81 mutation in S. cerevisiae (Toh-e et al. 1973; Ueda et al. 1975), we tried to isolate suppressor mutants from the Hppho81∆ strain by UV mutagenesis. Approximately 23,000 colonies were screened for APase activity on both high-Pi and low-Pi plates, and three clones (M1, M8 and M11) exhibited the PhoC phenotype (Fig. 1a). The three isolated strains were each crossed with the strain H76-1B (Hppho81Δ), and the resultant diploid hybrids were tested for APase activity. None of the hybrids showed APase activity (i.e., they all had the Pho− phenotype), indicating that the suppressor mutation in each of the isolates was recessive.

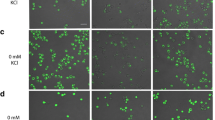

Colony staining assay of APase production in H. polymorpha mutants. APase activity was determined by a colony-staining assay in high-Pi and low-Pi media. a Strains M1, M8, and M11 were isolated by screening mutants obtained after UV mutagenesis of NY-1 (pho81∆). b Suppressor mutants KYC1385 and KYC1388 were derived from the original suppressor mutants M1 and M8, respectively, and both carried the pho81Δ mutation. They were transformed with either the control plasmid (pFL26), or the HpPHO80 (YZ77) or HpPHO85 (YZ78) expression plasmid. c Strains R1 and R2 were isolated by screening mutants obtained after random integration of pREMI-Z into AP2 (pho80). d Suppressor mutant YZS28 was derived from the original suppressor mutant R1, and carried the PHO80 + gene and the inserted pREMI-Z fragment. YZS28 was subsequently transformed with pFL21 (control) or YZ14 (HpPHO4) plasmid

Next, the diploids resulting from each cross were sporulated and dissected. Of 9–16 tetrads examined in each case, almost all showed 2 PhoC:2 Pho− segregation, indicating that the suppressor mutations each occurred in a single nuclear gene. Using the PhoC segregants, complementation tests were done among the three isolates and the Hppho80 and Hppho85 mutants. The results showed that the mutations in M1 and M11 occurred in the same gene, which was allelic to HpPHO80, whereas the mutation in M8 was located at the HpPHO85 locus. Furthermore, the suppressor mutations of M1 and M8 were complemented by the HpPHO80 (YZ77)- and the HpPHO85 (YZ78)-expression plasmids, respectively (Fig. 1b). The M1 (pho81Δ pho80-101) and M8 (pho81Δ pho85-8) mutants exhibited levels of APase production similar to those of the null mutants of each gene (Table 3). Thus, it is likely that a cyclin–CDK–CKI system regulates APase expression in H. polymorpha in a manner similar to S. cerevisiae.

Isolation of Hppho4 as a suppressor of Hppho80 and Hppho85

Next, we constructed Hppho4Δ and Hppho2Δ strains. As expected, the Hppho4∆ strain showed the Pho− phenotype under the low-Pi condition (Table 3). The Hppho2Δ strain, however, did not show a defect in the production of APase (Table 3), as has been reported for deletion of CgPHO2 (Kerwin and Wykoff 2010).

We explored the downstream of HpPHO80 by screening suppressors of the Hppho80 mutation (strain AP2; Hppho80 leu1) that were generated by random integration of the pREMI-Z plasmid (van Dijk et al. 2001). For unknown reasons, this method did not work well with our strain and many false-positive colonies were obtained after transformation. We therefore replica-plated the first transformants onto fresh YPAD plates supplemented with 200 μg/ml of zeocin before testing APase activity. Among approximately 9100 zeocin-resistant transformants examined, two Pho− mutants (R1 and R2) were isolated (Fig. 1c). Diploids generated between each of these mutants and strain KYC1389 (Hppho80 ade11) exhibited the PhoC phenotype, indicating that the two mutations were recessive. Furthermore, analysis of 25 tetrads for each diploid showed 2 PhoCZeoS:2 Pho−ZeoR segregation, and the two mutations did not complement each other, suggesting that they occurred in the same nuclear gene.

Sequence analysis of zeocin-resistant plasmid DNA recovered from the EcoRI-digested genomic DNA of the mutant R1 showed that the pREMI-Z fragment was inserted at the promoter of HpPHO4 (52-bp upstream of its ATG initiation codon). To examine whether the wild-type HpPHO4 gene in a plasmid could complement the mutation of R1, we transformed a strain (YZS28) carrying the mutation of R1 with an HpPHO4 expression plasmid (YZ14). The resultant transformant exhibited the wild-type APase phenotype, as shown in Fig. 1d. Therefore, we concluded that the two suppressors of the Hppho80 mutation were allelic to Hppho4.

We also isolated suppressors of the Hppho85 mutation by UV mutagenesis of strain KYC1390 (Hppho85 ura3). Of approximately 18,000 survival colonies, six suppressor mutants (YZS66, YZS69, YZS72, YZS73, YZS77 and YZS85) were obtained. All diploid cells generated between each mutant and KYC1404 (Hppho85 leu1) showed the PhoC phenotype, indicating that all of the suppressors were recessive. Among the diploid strains, those involving YZS72 and YZS73 as representative suppressors were subjected to tetrad analysis. Of 20 or 30 tetrads from the diploids formed between, respectively, YZS73 or YZS72 and KYC1404, the APase phenotype segregated in a 2 PhoC:2 Pho− fashion. Furthermore, a complementation test among the six mutants indicated that all suppressors were mutated within the same gene. By backcrossing YZS73 to the wild-type strain BY4330, a Pho− clone without an Hppho85 mutation (YZS135) was obtained. The strain YZS135 failed to complement the deficient APase phenotype of YZS28 (Hppho4::pREMI-Z), indicating that the suppressor gene is allelic to the HpPHO4 gene. Given the results of the mutant analysis and suppressor isolation, we infer that HpPHO4 encodes a transcription factor required for expression of the APase gene (PHO1) under the low-Pi condition, and that HpPho80 and HpPho85 negatively regulate the function of HpPho4.

Isolation of PhoC mutants

To further explore the PHO pathway of H. polymorpha, particularly the genes functioning upstream of HpPHO81, we screened for mutants showing the PhoC phenotype. The wild-type strain BY4329 was subjected to mutagenesis by UV irradiation, and the colonies resulting on a YPAD plate were transferred to a high-Pi plate, incubated at 37 °C for 1 day, and then tested for APase by the colony staining method. Among approximately 25,000 colonies, 38 mutants showing an unambiguous PhoC phenotype were isolated. The 38 isolated PhoC mutants were then crossed with the wild-type strain BY4330, and the resulting diploids were grown on high-Pi plate and tested for APase activity by colony staining. Four of the 38 mutants were dominant constitutive and the others were recessive constitutive.

For further genetic analysis of the recessive mutants, hybrids generated in the above test were randomly picked up, sporulated and dissected. Among tetrads showing 2+:2− segregation of APase production on YPAD plates, appropriate segregants were chosen and used in complementation tests with other recessive mutants. As a result, the recessive constitutive mutants were divided into three complementation groups, one of which was allelic to HpPHO80 (11 strains). The remaining two complementation groups were associated with new genes, which were designated PHO51 and PHO53. Mutants with mutations of PHO51 were most frequently isolated (21 strains).

The four dominant mutants (termed AP4, AP5, C12, and C51) were also subjected to tetrad analysis after crossing with the wild-type strain BY4330. As a result, the Pho phenotype segregated as 2+:2− in each ascus on high-Pi plates, suggesting that the mutations in each of the four mutants are located in a single gene. In the case of S. cerevisiae, the ScPHO81 C allele has been reported to be dominant constitutive (Creasy et al. 1993; Ogawa et al. 1995). We therefore considered that the present mutants might contain an HpPHO81 C allele. Diploids generated between each dominant constitutive mutant and NY-1 (Hppho81∆) were constructed and subjected to tetrad analysis. The Pho phenotype of 8–12 tetrads examined for each diploid showed the 2+:2− segregation pattern on both high-Pi and low-Pi plates and no wild-type recombinant was observed. This observation further suggested that the four dominant constitutive mutants were HpPHO81 C mutants.

Four alleles of ScPHO81 C have been reported to carry the mutation at the N-terminal region of the Pho81 protein (Creasy et al. 1993; Ogawa et al. 1995). To identify the mutation points of the HpPHO81 C alleles, we cloned the alleles of the four HpPHO81 C mutant strains by a PCR-based technique and determined their nucleotide sequences. Notably, the point of mutation of each HpPHO81 C allele differed, being located at not only the N-terminus (S144F in AP4), but also the minimum domain (Y614 N in C12 and F618L in C51) and the C-terminus (N968T in AP5) (Fig. S2).

PHO51 and PHO53 function upstream of HpPHO81 in the PHO pathway

To determine the position of the PHO51 and PHO53 genes in the PHO pathway, we examined the epistatic relationship between the Hppho81 mutation and the pho51 or pho53 mutation. We considered that if pho51 is epistatic to Hppho81, then the pho51 Hppho81 double mutant would show the PhoC phenotype. In the opposite case—that is, if Hppho81 is epistatic to pho51—the double mutant should show the Pho− phenotype even in the low-Pi condition. We crossed NY-1 (Hppho81) and C5 (pho51) and performed the tetrad analysis. As shown in Table 5, tetrads exhibited only the 2+:2− segregation pattern of APase production in the low-Pi condition, but 1+:3− (tetratype) and 0+:4− (non-parental ditype) segregations were observed in the high-Pi condition, indicating that Hppho81 is epistatic to pho51.

In the case of pho53, tetrad analysis of diploids generated by crossing with Hppho81 showed a similar segregation pattern of Pho phenotype. Thus, the results of epistasis analysis with Hppho81 suggest that both PHO51 and PHO53 act upstream of HpPHO81 in the PHO pathway.

Discussion

The PHO pathway is one of the best model systems for studying the gene regulation network, because substantial information on the function of the regulatory genes in the PHO system of S. cerevisiae has been accumulated in recent decades. In this study, we have focused on the methylotrophic yeast H. polymorpha—a species that diverged from S. cerevisiae more than 100 million years ago (Dujon et al. 2004)—and have characterized its PHO pathway genetically. We confirmed that four genes (HpPHO81, HpPHO80, HpPHO85 and HpPHO4) are involved in the PHO pathway of H. polymorpha by comparative genomic analysis and mutant analysis. The HpPHO81 gene complemented the S. cerevisiae pho81 deletion strain, and several dominant constitutive HpPHO81 C mutations were isolated, similar to those isolated for S. cerevisiae. The epistatic relationship between Hppho81 mutation and Hppho80 or Hppho85 mutation was also found to be conserved in the PHO pathway of H. polymorpha. Moreover, Hppho4 mutation was shown to be epistatic to both Hppho80 and Hppho85 mutation. The quantitative real-time PCR analysis of PHO1 expression under both high-Pi and low-Pi conditions in the relevant mutants indicated that APase (Pho1) production of H. polymorpha was regulated at transcriptional level by the PHO pathway (Table 3). We therefore propose that the core regulatory components of the PHO pathway are conserved in H. polymorpha even though it separated from its common ancestor with S. cerevisiae before duplication of the whole genome during the evolution of ascomycetous yeasts. A schematic of the PHO pathway in H. polymorpha is shown in Fig. 2.

Current genetic interaction model of the PHO pathway in H. polymorpha. Under the low-Pi condition, the cyclin–CDK (HpPho80–HpPho85) complex is inhibited by the CDK inhibitor HpPho81 and the transcriptional activator HpPho4 induces transcription of the PHO1 gene. Under the high-Pi condition, the HpPho80–HpPho85 complex phosphorylates and inhibits the function of HpPho4 in the same way as the homologous genes in S. cerevisiae. In this condition, Pho51 and Pho53 directly or indirectly inhibit the function of HpPho81

Through characterization of the PHO pathway in H. polymorpha, we can infer an evolutionary scheme for development of the phosphate starvation response. Core components of the PHO pathway have been reported to be conserved, or partially conserved, in several species in the phylum Ascomycota. For example, according to Kerwin and Wykoff (2010), the cyclin–CDK–CKI complex is conserved in C. glabrata, a species that is closely related to S. cerevisiae. In N. crassa, the phosphate starvation response involves four regulatory genes—nuc-1, preg, pgov and nuc-2 (Kang and Metzenberg 1990; Littlewood et al. 1975; Toh-e and Ishikawa 1971)—corresponding to ScPHO4, ScPHO80, ScPHO85 and ScPHO81, respectively. Similar to the pathway in S. cerevisiae, the NUC-2 protein inhibits the function of the PREG–PGOV complex, thereby facilitating translocation of NUC-1 into the nucleus under conditions of Pi shortage (Gras et al. 2009). In A. nidulans, AnPho80 and AnPho4 play their expected negative role and positive role, respectively, in the PHO pathway; however, the most likely orthologues of ScPho81 and ScPho85 are not involved in this system (Wu et al. 2004). Significantly different from species in the above-mentioned Ascomycota, S. pombe has no homolog of ScPHO81 and its closest homologs of ScPHO80 and ScPHO85 do not seem to be involved in regulating APase production (Henry et al. 2011). In the phylum Basidiomycota, core components of the PHO pathway are conserved in the species C. neoformans (Toh-e et al. 2015). Therefore, it seems likely that core components of the PHO pathway existed in the common ancestor of fungi; however, some species have targeted these core components to other types of systems during the course of evolution.

Because the PhoC phenotype of the pho51 and pho53 mutants was found to be dependent on HpPHO81 gene function, we infer that the functional positions of PHO51 and PHO53 are located upstream of HpPHO81 in the PHO pathway (Fig. 2). At present, the function of the PHO51 and PHO53 genes remains unclear, and the corresponding genes in the S. cerevisiae PHO pathway are unknown. Among several recessive constitutive mutations reported in S. cerevisiae, many are located upstream of PHO81, including PHO84, PHO86 and PMA1, which are required for function of the phosphate transport system in vivo (Ueda et al. 1975; Lau et al. 1998); PLC1, ARG82 and KCS1, which are involved in the synthesis of inositol pyrophosphates; and ADK1, which encodes adenylate kinase (Auesukaree et al. 2005). Therefore, it is likely that PHO51 and PHO53 might encode proteins involved in phosphate transport or inositol polyphosphate synthesis. In addition, it has been reported that the disruption of either ACC1, encoding acetyl-CoA carboxylase, or PHO23, encoding a component of the Rpd3L histone deacetylase complex, leads to constitutive APase activity and this phenotype is also PHO81-dependent (Lau et al. 1998). Thus, PHO51 and PHO53 might encode proteins involved in similar cellular functions. At present, we are trying to characterize these two new genes by bioinformatics analysis of whole-genome sequences, as described by Iida et al. (2014). Furthermore, newly constructed H. polymorpha YCp-type vectors, which will be described elsewhere, will facilitate both generation of a stable H. polymorpha genomic DNA library and identification of causative mutations in the near future. Clarification of these mutations might lead to better understanding of the PHO system not only in H. polymorpha, but also in other yeasts. In addition, it may provide clues to the unsolved problems of the PHO pathway in S. cerevisiae.

In S. cerevisiae, regulation of the kinase activity of the Pho80–Pho85 complex in response to phosphate concentration is enforced by the Pho81 CKI (Ogawa et al. 1995; Schneider et al. 1994). The Pho81 CKI is constitutively associated with Pho80–Pho85 (Schneider et al. 1994). A small-molecule ligand, IP7, interacts noncovalently with Pho80–Pho85–Pho81 and induces additional interactions between Pho81 and Pho80–Pho85 that prevent substrates from accessing the active site of the kinase (Lee et al. 2007, 2008). A particular domain of Pho81—termed the Pho81 minimum domain—is essential for inhibiting both the kinase activity of Pho80–Pho85 toward its Pho4 target and interaction with IP7 (Ogawa et al. 1995; Lee et al. 2008). Pho80 has two regions for binding to Pho4 and Pho81 (Huang et al. 2007). Alignment of ScPho81 with HpPho81 shows that the minimum domain is well conserved across the two Pho81 proteins (Fig. S2), suggesting that, similar to ScPho81, HpPho81 might be able to bind to the HpPho80–HpPho85 complex and might be activated by IP7. Indeed, the HpPHO81 gene can function as a CKI in S. cerevisiae pho81∆ cells, as shown in Table 4. On the other hand, we found that the mutation points of the HpPHO81 C allele were located not only in the N-terminus, but also in the minimum domain and the C-terminus. The mutations in PHO81 C probably result in stronger binding between Pho81C and Pho80–Pho85, making it always win during competition with the wild-type Pho81. Undoubtedly, structural data and detailed biochemical analysis will reveal more clues to the mechanism of Pho80–Pho85 regulation by IP7 and Pho81.

Taking all of these observations together, we conclude that the main components of the PHO pathway identified in S. cerevisiae are conserved in the methylotrophic yeast H. polymorpha, although these two organisms separated from each other before the occurrence of whole-genome duplication during the course of evolution. Moreover, it seems that the CKI–cyclin–CDK regulatory system is a basic type of the PHO pathway among yeasts.

References

Auesukaree C, Tochio H, Shirakawa M, Kaneko Y, Harashima S (2005) Plc1p, Arg82p, and Kcs1p, enzymes involved in inositol pyrophosphate synthesis, are essential for phosphate regulation and polyphosphate accumulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem 280:25127–25133

Creasy CL, Madden SL, Bergman LW (1993) Molecular analysis of the PHO81 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res 21:1975–1982

Dujon B (2010) Yeast evolutionary genomics. Nat Rev Genet 11:512–524

Dujon B, Sherman D, Fischer G et al (2004) Genome evolution in yeasts. Nature 430:35–44

Estill M, Kerwin-Iosue CL, Wykoff DD (2015) Dissection of the PHO pathway in Schizosaccharomyces pombe using epistasis and the alternate repressor adenine. Curr Genet 61:175–183. doi:10.1007/s00294-015-0544-4

Gras DE, Silveira HC, Peres NT, Sanches PR, Martinez-Rossi NM, Rossi A (2009) Transcriptional changes in the nuc-2A mutant strain of Neurospora crassa cultivated under conditions of phosphate shortage. Microbiol Res 164:658–664

Henry TC, Power JE, Kerwin CL, Mohammed A, Weissman JS, Cameron DM, Wykoff DD (2011) Systematic screen of Schizosaccharomyces pombe deletion collection uncovers parallel evolution of the phosphate signal transduction pathway in yeasts. Eukaryot Cell 10:198–206

Huang K, Ferrin-O’Connell I, Zhang W, Leonard GA, O’Shea EK, Quiocho FA (2007) Structure of the Pho85–Pho80 CDK–cyclin complex of the phosphate-responsive signal transduction pathway. Mol Cell 28:614–623

Iida N, Yamao F, Nakamura Y, Iida T (2014) Mudi, a web tool for identifying mutations by bioinformatics analysis of whole-genome sequence. Genes Cells 19:517–527

Kaffman A, Herskowitz I, Robert T, O’Shea EK (1994) Phosphorylation of the transcription factor Pho4 by a cyclin–CDK complex, Pho80–Pho85. Science 263:1153–1156

Kaffman A, Rank NM, O’Neill EM, Huang LS, O’Shea EK (1998a) The receptor Msn5 exports the phosphorylated transcription factor Pho4 out of the nucleus. Nature 396:482–486

Kaffman A, Rank NM, O’Shea EK (1998b) Phosphorylation regulates association of the transcription factor Pho4 with its import receptor Pse1/Kap121. Genes Dev 12:2673–2683

Kang S, Metzenberg RL (1990) Molecular analysis of nuc-1+, a gene controlling phosphorus acquisition in Neurospora crassa. Mol Cell Biol 10:5839–5848

Kang HJ, Chang M, Kang CM, Park YS, Yoon BJ, Kim TH, Yun CW (2014) The expression of PHO92 is regulated by Gcr1, and Pho92 is involved in glucose metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Genet 60:247–253. doi:10.1007/s00294-014-0430-5

Kerwin CL, Wykoff DD (2009) Candida glabrata PHO4 is necessary and sufficient for Pho2-independent transcription of phosphate starvation genes. Genetics 182:471–479

Lau W-TW, Schneider KR, O’Shea EK (1998) A genetic study of signaling processes for repression of PHO5 transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 150:1349–1359

Lee YS, Mulugu S, York JD, O’Shea EK (2007) Regulation of a cyclin–CDK–CDK inhibitor complex by inositol pyrophosphates. Science 316:109–112

Lee YS, Huang K, Quiocho FA, O’Shea EK (2008) Molecular basis of cyclin–CDK–CKI regulation by reversible binding of an inositol pyrophosphate. Nat Chem Biol 4:25–32

Littlewood BS, Chia W, Metzenberg RL (1975) Genetic control of phosphate-metabolizing enzymes in Neurospora crassa: relationships among regulatory mutations. Genetics 79:419–434

Ljungdahl PO, Daignan-Fornier B (2012) Regulation of amino acid, nucleotide, and phosphate metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 190:885–929

Maekawa H, Kaneko Y (2014) Inversion of the chromosomal region between two mating type loci switches the mating type in Hansenula polymorpha. PLoS Genet 10:e1004796. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004796

Miller JH (1972) Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, New York

Ogawa N, Noguchi K, Sawai H, Yamashita Y, Yompakdee C, Oshima Y (1995) Functional domain of Pho81p, an inhibitor of Pho85p protein kinase, in the transduction pathway of Pi signal in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 15:997–1004

Orkwis BR, Davies DL, Kerwin CL, Sanglard D, Wykoff DD (2010) Novel acid phosphatase in Candida glabrata suggests selective pressure and niche specialization in the phosphate signal transduction pathway. Genetics 186:885–895

Oshima Y (1997) The phosphatase system in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Genet Syst 72:323–334

Partow S, Siewers V, Bjørn S, Nielsen J, Maury J (2010) Characterization of different promoters for designing a new expression vector in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 27:955–964

Phongdara A, Merckelbach A, Keup P, Gellissen G, Hollenberg CP (1998) Cloning and characterization of the gene encoding a repressible acid phosphatase (PHO1) from the methylotrophic yeast Hansenula polymorpha. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 50:77–84

Schneider KR, Smith RL, O’Shea EK (1994) Phosphate-Regulated inactivation of the kinase Pho80–Pho85 by the CDK inhibitor Pho81. Science 266:122–126

Sherman F (1991) Getting started with yeast. Meth Enzymol 194:3–21

Toh-e A, Ishikawa T (1971) Genetic control of the synthesis of repressible phosphatases in Neurospora crassa. Genetics 69:339–351

Toh-e A, Ueda Y, Kakimoto S, Oshima Y (1973) Isolation and characterization of acid phosphatase mutants in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol 113:727–738

Toh-e A, Ohkusu M, Li HM, Shimizu K, Takahashi-Nakaguchi A, Gonoi T, Kawamoto S, Kanesaki Y, Yoshikawa H, Nishizawa M (2015) Identification of genes involved in the phosphate metabolism in Cryptococcus neoformans. Fungal Genet Biol 80:19–30

Ueda Y, Toh-e A, Oshima Y (1975) Isolation and characterization of recessive, constitutive mutations for repressible acid phosphatase synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol 122:911–922

van Dijk R, Faber KN, Hammond AT, Glick BS, Veenhuis M, Kiel JA (2001) Tagging Hansenula polymorpha genes by random integration of linear DNA fragments (RALF). Mol Genet Genom 266:646–656

van Zutphen T, Baerends RJ, Susanna KA, de Jong A, Kuipers OP, Veenhuis M, van der Klei IJ (2010) Adaptation of Hansenula polymorpha to methanol: a transcriptome analysis. BMC Genom 11:1. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-11-1

Wu D, Dou X, Hashmi SB, Osmani SA (2004) The Pho80-like cyclin of Aspergillus nidulans regulates development independently of its role in phosphate acquisition. J Biol Chem 279:37693–37703

Yadav KK, Singh N, Rajasekharan R (2015) Responses to phosphate deprivation in yeast cells. Curr Genet. doi:10.1007/s00294-015-0544-4

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by the Endowed Chair Funding (2011) of Institute for Fermentation, Osaka (IFO), Japan. The authors also thank the National BioResource Project Japan (YGRC/NBRP) for offering the strains and plasmid, Dr. Yasuyoshi Sakai (Kyoto University) for a gift of pREMI-Z plasmid, Kohji Nagashima for technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by M. Kupiec.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

294_2016_565_MOESM2_ESM.pdf

Supplementary Fig. S1 Amino acid sequence alignment of Pho4 proteins in three yeast species. The amino acid sequences of the Pho4 protein in S. cerevisiae (Sc_pho4), C. glabrata (Cg_pho4) and H. polymorpha (Hp_pho4) were aligned by Clustal Omega. The known phosphorylation sites of ScPho4 are indicated by boxes (PDF 41 kb)

294_2016_565_MOESM3_ESM.pdf

Supplementary Fig. S2 Amino acid sequence alignment of Pho81 proteins in three yeast species. The amino acid sequences of the Pho81 protein in S. cerevisiae (Sc_pho81), C. glabrata (Cg_pho81) and H. polymorpha (Hp_pho81) were aligned by Clustal Omega. The minimum domain of ScPho81 is denoted by a box. The mutation point in each HpPHO81 C mutant is indicated by an asterisk (PDF 52 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, Y., Yuikawa, N., Nakatsuka, H. et al. Core regulatory components of the PHO pathway are conserved in the methylotrophic yeast Hansenula polymorpha . Curr Genet 62, 595–605 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00294-016-0565-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00294-016-0565-7