Abstract

Bacterial infections are the most common cause for treatment-related mortality in patients with neutropenia after chemotherapy. Here, we discuss the use of antibacterial prophylaxis against bacteria and Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) in neutropenic cancer patients and offer guidance towards the choice of drug. A literature search was performed to screen all articles published between September 2000 and January 2012 on antibiotic prophylaxis in neutropenic cancer patients. The authors assembled original reports and meta-analysis from the literature and drew conclusions, which were discussed and approved in a consensus conference of the Infectious Disease Working Party of the German Society of Hematology and Oncology (AGIHO). Antibacterial prophylaxis has led to a reduction of febrile events and infections. A significant reduction of overall mortality could only be shown in a meta-analysis. Fluoroquinolones are preferred for antibacterial and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole for PCP prophylaxis. Due to serious concerns about an increase of resistant pathogens, only patients at high risk of severe infections should be considered for antibiotic prophylaxis. Risk factors of individual patients and local resistance patterns must be taken into account. Risk factors, choice of drug for antibacterial and PCP prophylaxis and concerns regarding the use of prophylactic antibiotics are discussed in the review.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Patients with hematological and oncological diseases are at increased risk for bacterial infections and pneumonia caused by Pneumocystis jirovecii (PCP) because of their disease-related and therapy-induced immunosuppression. As infections are the leading cause for non-relapse mortality, broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy is introduced as soon as an infectious problem is suspected. Despite early empirical antibiotic therapy, the infection-related mortality in neutropenic cancer patients is 4–7 % [1, 2]. The administration of systemic antibacterial prophylaxis may aim at a reduction of severe infections, a delay of the onset of such infections to a later phase of neutropenia, avoidance of infection-related treatment delays, reduction of hospitalization, reduction of treatment costs or a combination of these goals. To reduce the risk of infectious complications during the period of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia, various prophylactic approaches including the systemic use of antibiotics were introduced and widely studied. The decision for or against the administration of a prophylactic antibiotic regime is guided by the risk of an individual patient to acquire a severe, life-threatening infection, carefully balanced against the potential risks of long-term administration of a broad-spectrum antibacterial agent with systemic activity. Several studies have shown that antibacterial prophylaxis led to a reduction of febrile events and documented infections, their tolerability is generally good and hospitalization may be avoided or shortened, resulting in cost saving. On the other hand, the concept of antibiotic prophylaxis is challenged because of possible side effects such as development of resistance and toxicity of the drugs.

For this review, papers on antibacterial and PCP prophylaxis published in scientific journals from September 2000 to January 2012 were searched and evaluated according to the 2001 evidence-based medicine criteria used by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) (Table 1) [3]. The authors assembled in January 2012 to develop practice recommendations based on the recent literature. These recommendations were then extensively discussed at the Infectious Diseases Working Party of the German Society of Hematology and Oncology (AGIHO) plenary meeting, resulting in an agreement regarding each recommendation. This manuscript summarizes the recommendations on antibacterial and PCP prophylaxis for neutropenic cancer patients resulting from this process.

Guidelines for antiviral and antifungal prophylaxis can be found in other publications of the AGIHO [4, 5]. Furthermore, prophylaxis of patients with allogeneic stem cell transplantation is addressed in a separate guideline of the AGIHO [6].

Definitions

Neutropenia

Neutropenia is defined as a neutrophil count below 500/μl or <1,000/μl with predicted decline to less than 500/μl within the next 2 days, or leukopenia <1,000/μl when there is no differential leukocyte count available.

IDSA grading system for ranking recommendations

Regarding the IDSA grading system for ranking recommendations, see Table 1.

Patients and risk factors

The risk of developing an infection following chemotherapy depends on the severity and duration of neutropenia [7, 8]. In a guideline published a decade ago, the AGIHO defined three risk groups depending on the duration of neutropenia — patients with an expected duration of neutropenia of less than 5 days generally are at low risk, whereas patients with an expected duration of neutropenia of more than 10 days are at high risk, with a risk of acquiring an infection exceeding 90 % [9]. Patients with an expected duration of neutropenia between 6 and 10 days were classified as intermediate risk group. Other guidelines divide the patients into two risk groups with neutropenia of more or less than 7 days based on two recently published clinical trials [1, 10–12]. Importantly, none of these classifications are based on prospective studies. However, judging the risk of an individual patient on his expected duration of neutropenia has become clinical practice in many centers. We will also assume two risk groups for easier applicability, the low-risk group being patients with an expected duration of neutropenia of less than 7 days and the high-risk group those patients with duration of neutropenia of 7 days or more or with additional risk factors.

Additional factors which may increase the risk of infection are the type and stage of the underlying malignancy, the remission status, disruption of physiological skin or mucosal barriers as well as age and comorbidities of an individual patient. Furthermore, the number and type of pretreatments or the use of other immunosuppressive agents such as high-dose glucocorticosteroids or lymphocyte-depleting substances may have an impact on the risk of infection. Patients receiving their first cycle of chemotherapy are at a higher risk of infection than in following cycles. However, if a febrile episode occurred during the first cycle, the risk of infection is increased in subsequent cycles of chemotherapy. Moreover, the “social environment,” including the availability of a direct caregiver, telephone, option of quick transportation from home to hospital, residence within a defined maximum distance from the hospital and appropriate verbal communication and intellectual understanding of an individual patient should be considered for the decision of anti-infective prophylaxis [8, 13–16] (Table 2).

In patients with autologous stem cell transplantation, the risk of infection depends primarily on the length of neutropenia which is usually longer than 7 days. More detailed information can be found in the relevant guideline [17].

The use of the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab or anti-CD52 antibody alemtuzumab leads to an increased incidence of fungal, viral or protozoal infections [18–21], while a substantially increased risk of bacterial infections has not been reported [22–26].

Clinical presentation and spectrum of pathogens in neutropenic infections

In most cases of infection in a neutropenic patient, fever is the first sign [27]. Typical clinical symptoms such as local signs of infection as part of an inflammatory response may be missing. In approximately half of the patients, a focus of infection cannot be detected at the onset of fever; therefore, it is classified as fever of unknown origin (FUO). In up to a third of patients, bacteremia can be diagnosed [1, 28], with coagulase-negative staphylococci, α-hemolytic streptococci and Staphylococcus aureus being predominant among gram-positive pathogens. With regard to gram-negative pathogens, enterobacteria such as Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. as well as non-fermenters such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa predominate [29–31]. A gram-negative sepsis is still associated with substantial mortality [32]. For this reason, antibiotic prophylaxis using agents active against gram-negative bacteria, particularly fluoroquinolones, was introduced in many hospitals, resulting in an overall decrease of bacteremias, but also in an increased proportion of infections caused by gram-positive bacteria [33]. At present, the proportion of gram-positive pathogens in neutropenic patients with microbiologically documented infections is typically around 60–70 % [29, 31, 34, 35]; however, as this may differ substantially between cancer centers [36], the local epidemiology should always be considered before deciding on an antibacterial prophylaxis regimen.

Efficacy of prophylaxis

The efficacy of systemic antibacterial prophylaxis was investigated in a multitude of clinical trials and several meta-analyses. The results of the two most important large double-blind, placebo-controlled studies are described briefly: Bucaneve et al. examined the use of levofloxacin in 675 patients with hematological malignancies or solid tumors and an expected length of neutropenia (neutrophil count less than 1,000/μl) of more than 7 days. A significant reduction of febrile episodes and microbiologically documented infections, especially gram-negative bacteremias, could be shown in the levofloxacin arm. Mortality was lower in the levofloxacin group, but the study was not powered to show this with statistical significance [1]. In the study by Cullen et al. [12], 1,565 patients with solid tumors or lymphomas receiving outpatient chemotherapy were given levofloxacin or placebo for an expected period of neutropenia of less than 7 days. The incidence of febrile episodes, probable infections and hospitalization for infection could be reduced significantly. Also, there were fewer severe infections and a lower overall mortality in the prophylaxis group, but this difference was not statistically significant [12].

These observations were confirmed in a large meta-analysis comprising a total of 13,579 patients from 109 studies conducted between 1973 and 2010 [37]. Most of the studies included high-risk patients with hematological diseases such as acute leukemias and compared different prophylactic strategies with placebo or no intervention. Due to the larger number of patients included in the meta-analysis compared to the single trials, a significant reduction of infection-related death with a risk ratio (RR) of 0.61 (95 % confidence interval [CI], 0.48–0.77) and a reduction in all-cause mortality (RR 0.66; 95 % CI, 0.55–0.79) were calculated for patients receiving antibacterial prophylaxis as compared to placebo or no intervention. A decrease in all-cause mortality could also be shown in the subgroup of 3,776 patients included from studies testing fluoroquinolone prophylaxis versus no prophylaxis (RR 0.54; 95 % CI, 0.40–0.74). Microbiologically documented gram-negative as well as gram-positive infections including bacteremias were significantly reduced in patients receiving antibacterial prophylaxis. An increase of 3.6 % in adverse events due to prophylaxis as compared to no prophylaxis is reported with 2.1 % more events (3.9 % versus 1.8 %) leading to treatment discontinuation [37].

A meta-analysis including only randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled trials from 1987 to 2005 with a total of 2,721 patients could not demonstrate a significant, but only a trend towards, reduction of overall mortality [38], while efficacy data were consistent with the study from Bucaneve et al. and with the 2012 meta-analysis [1, 37]. It has to be kept in mind that this meta-analysis was strongly influenced by the non-infectious mortality among low-risk patients in the Cullen et al. study, which might obscure a potential survival benefit with regard to the infection-related mortality (Table 3).

Antibacterial prophylaxis, particularly with fluoroquinolones, can prevent febrile episodes, clinically or microbiologically documented bacterial infections including bacteremias and hospitalization of outpatients. A reduction in infection-related as well as all-cause mortality could be shown in a large meta-analysis [37]. In order to derive recommendations from the data described above, the risk reduction has to be weighed against adverse effects, especially the development of resistance to widely used antibacterial agents among clinically relevant pathogens. A reduction of overall mortality can be assumed in high-risk populations with a number needed to treat (NNT) below 50 (43 according to the study of Bucaneve et al., 34 according to the meta-analysis of Gafter-Gvili et al.) and avoidance of neutropenic fever with a NNT of around 5 [1, 37, 39]. As with other interventions, NNT decreases with increasing underlying risk. Therefore, prophylaxis is recommended in high-risk patients. Concerning avoidance of fever and infections, this is a strong recommendation; concerning mortality reduction, the recommendation is weaker (Table 4). In low-risk patients, a reduction of neutropenic fever and avoidance of hospitalization can be achieved. This effect is most pronounced during the first cycle of chemotherapy. On the other hand, a reduction of mortality was not unequivocally shown for low-risk patients. One meta-analysis showed a mortality reduction with a NNT of 72 [39], but it included older studies with an unacceptably high baseline event rate to be attributed to low-risk patients. Assuming that in low-risk patients a similar relative risk reduction as in high-risk patients can be achieved, the NNT to prevent one infection-related death would be around 250 at a baseline risk of 1 % and a relative risk of 0.6 (i.e., otherwise healthy individuals with low-intensity chemotherapy). In addition, the prophylactic administration of a fluoroquinolone in low-risk patients would prohibit the use of a fluoroquinolone for treatment of infection in the outpatient setting. Therefore, antibacterial prophylaxis can generally not be recommended in low-risk patients. In specific situations such as the first chemotherapy cycle [15], aggressive cytostatic regimens with high baseline infection rate or in elderly patients; however, it may be considered because it reduces the incidence of infections and febrile episodes.

Substances for antibacterial prophylaxis

Studies conducted in the 1970s used non-absorbable antibiotics such as colistin, polymyxin B or neomycin for selective bowel decontamination. Due to the lack of systemic activity, gastrointestinal tolerability problems and the risk of selection of resistant bacteria, most institutions have switched to trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX) or fluoroquinolones. These substances have a broad spectrum of activity and are well absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract. TMP/SMX is not active against P. aeruginosa, and resistance to this drug combination among gram-negative target pathogens such as E. coli or Klebsiella spp. has been observed already in the 1990s. However, significant differences in clinical efficacy have not been shown in direct comparisons [40–42]. Both types of drugs show similar risk reductions of the outcome parameters mentioned above in comparison to placebo [37].

TMP/SMX is less well tolerated as compared with fluoroquinolones (relative risk for side effects requiring discontinuation about 2 compared to quinolones by both direct and indirect comparison [37]), and it may be associated with bone marrow toxicity in patients given this drug combination daily for more than 2–3 weeks.

Therefore, if a high local resistance rate and an individual intolerance to fluoroquinolones are excluded, a fluoroquinolone should be preferred in patients in whom systemic antibacterial prophyaxis is indicated (A-II, Table 4).

The fluoroquinolones available for clinical use differ in their spectrum of activity. Ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin were most frequently tested in clinical trials. Compared to ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin is less effective against P. aeruginosa, but has the advantage of activity against gram-positive bacteria such as Streptococcus spp. In 2012, a warning regarding the off-label use of levofloxacin was issued because of rare but severe side effects including life-threatening hepatotoxicity. In Germany, levofloxacin is not approved for the prophylactic use in the setting of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia, whereas ciprofloxacin is. Considering this fact and in the light of the recent box warning, the authors recommend to prefer ciprofloxacin for antibacterial prophylaxis in neutropenic cancer patients.

While moxifloxacin has a broad activity against aerobic and anaerobic gram-positive and gram-negative pathogens, it has no efficacy against P. aeruginosa and appears to be associated with a higher risk of Clostridium difficile-associated enterocolitis than levofloxacin [43]. As yet, no properly designed clinical study showing a benefit of moxifloxacin for antibacterial prophylaxis in neutropenic cancer patients has been reported. A recently published trial has demonstrated a reduction of bacteremias by moxifloxacin in a small number of patients undergoing autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation [44].

Combination of a fluoroquinolone with an agent active against gram-positive bacteria

In order to prevent gram-positive infections, combinations of fluoroquinolones with antibiotics active against gram-positive pathogens such as oral penicillin, vancomycin or a macrolide have been studied in neutropenic patients. A randomized placebo-controlled study investigated the use of ciprofloxacin in combination with roxithromycin versus no antibiotic prophylaxis in patients with small cell lung cancer during the first cycle of chemotherapy. In the prophylaxis group, the incidence of febrile leukopenia, documented gram-positive and gram-negative infections and infection-associated deaths were significantly reduced [45]. A comparison with single-agent ciprofloxacin was not included in this study. Several small trials compared combination prophylaxis with fluoroquinolone prophylaxis alone. Two meta-analyses including more than 1,200 patients found a significant reduction in gram-positive infections and septicemia with the addition of an antibiotic active against gram-positive pathogens, however, a significant reduction of clinically documented infections, febrile neutropenia or mortality could not be demonstrated [37, 46]. On the other hand, significantly more side effects were reported in patients on combination therapy. In particular, the administration of rifampin resulted in a significantly increased rate of side effects such as gastrointestinal intolerance or abnormal liver function tests.

In summary, the addition of prophylactic antibiotics with specific activity against gram-positive pathogens to a fluoroquinolone is not recommended (E-II, Table 4).

Beginning and duration of prophylaxis

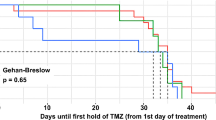

There are no comparative studies addressing the question when to start prophylactic antibiotics and how long to administer them. In those patients with expected short duration of neutropenia (solid tumors, lymphomas), in whom antibacterial prophylaxis is considered at all, prophylaxis is usually started after the end of chemotherapy and given throughout the period of neutropenia [12, 45]. In high-risk patients, however, antibiotic prophylaxis in clinical trials was administered almost exclusively from the start of chemotherapy until the end of neutropenia or until the onset of systemic antimicrobial therapy [1, 47]. In patients receiving induction chemotherapy for acute leukemia, prophylaxis should begin with the first day of chemotherapy because of the functional neutropenia induced by the disease itself. With the end of neutropenia or onset of systemic antimicrobial treatment, antibiotic prophylaxis should be stopped (B-III). The use of quinolones for empirical treatment is not recommended if prior prophylaxis has been carried out with a fluoroquinolone (A-III, Table 4).

If a cytostatic treatment in acute leukemia patients is given without antibacterial prophylaxis, an intensive clinical monitoring is required to ensure an immediate start of antibiotic therapy in case of a suspected infection.

Concerns on resistance development

One of the main concerns regarding antibiotic prophylaxis in any patient population is the development or selection of multidrug-resistant pathogens. This has led some experts to withhold a recommendation for antibiotic prophylaxis in neutropenic cancer patients [11]. Regarding the risk of the emergence of resistance, several issues need to be considered:

-

1.

Does antibacterial prophylaxis in cancer patients really lead to an excess increase in the proportion of multidrug-resistant pathogens?

-

2.

Are infections due to fluoroquinolone-resistant pathogens more threatening than infections from sensitive strains of the same pathogen?

-

3.

If there is an increase in multidrug-resistant pathogens, does it lead to an increased infection rate due to these pathogens and does this result in increased mortality?

-

4.

As a consequence, should a recommendation for antibacterial prophylaxis in neutropenic cancer patients be restricted to centers with a low (e.g., <20 %) prevalence of resistance against the prophylactic antibacterials (typically fluoroquinolones) among target pathogens such as E. coli or Klebsiella spp. since in areas with a high prevalence of resistance no benefit from this prophylaxis can be expected?

-

5.

Is it ethically justified to withhold a potentially beneficial antibacterial prophylaxis from cancer patients at risk for serious neutropenic infections today, in order to avoid an increasing risk of infections due to resistant pathogens in future patients?

While none of these questions can be answered definitely, there are some arguments to consider for most of them. Data regarding the additional effect of drug resistance on morbidity and mortality in hospital acquired infections are conflicting [48–50], whereas there is little doubt that hospital acquired infections by themselves pose a major problem and should generally be avoided if possible. This consideration rather favors the use of prophylactic antibiotics, since it has been shown that they reduce the likelihood of infections in neutropenic cancer patients. From a broader perspective, neutropenic cancer patients at risk of severe infections constitute a small proportion among patients who regularly receive antibiotic treatment, not to mention the widespread use of antibiotics in settings outside the health care system such as agriculture and livestock. Nonetheless, even such a small population may have an impact on the general epidemiology of infections, and reports of spread of resistant pathogens after the introduction of TMP/SMX or fluoroquinolone prophylaxis have to raise concern [51, 52]. In particular, multidrug-resistant E. coli and P. aeruginosa as well as methicillin-resistant S. aureus have been reported to play a relevant role [51]. However, this finding has not been confirmed unequivocally [53, 54]. The 2012 Cochrane meta-analysis on antibiotic prophylaxis in neutropenic cancer patients revealed an increase of infections due to resistant pathogens in patients receiving antibiotic prophylaxis with TMP-SMX, but not with fluoroquinolones [37]. Thus, it is not entirely certain if antibacterial prophylaxis using fluoroquinolones increases the incidence of infections with resistant strains. Also, moxifloxacin seems to have the most relevant potential for inducing C. difficile associated diarrhea [43], while studies on levofloxacin [55] or ciprofloxacin [56] prophylaxis did not report a similar increase in the incidence of C. difficile-associated enterocolitis [39].

In addition, in studies on discontinuation of antibacterial prophylaxis, an increase in (particularly gram-negative) bacteremias has been observed [52, 54, 57], sometimes even translating into a higher mortality rate [57]. Of note, although some authors report a lack of efficacy in case of a high incidence of resistance [58], this could not be confirmed by others [52, 53, 57]. Thus, a fixed threshold of for example <20 % prevalence of quinolone resistance for instituting quinolone prophylaxis as suggested by Bow [59] cannot be generally advised (E-III). In contrast, it seems more advisable to monitor development of resistance (A-III) and efficacy (B-III) on a regular basis in centres implementing antibiotic prophylaxis. The overall clinical benefit can then be deduced from local data and experience.

Antibiotic prophylaxis versus myeloid growth factors for infection prophylaxis

The administration of granulocyte (G-CSF) or granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factors (GM-CSF) is another possibility to prevent infectious complications. In studies, a reduction of bacterial infections could be shown by shortening the length of neutropenia by the use of these myeloid growth factors. Therefore, the use is generally recommended if the risk of febrile neutropenia is above 20 % [60–62]. Two questions arise, which of these strategies is more efficient, and can both strategies be combined? A formal meta-analysis comparing both strategies directly could not be performed due to the different evaluation endpoints of the two small single studies [63]. Indirect comparisons give the impression, that growth factors and prophylactic antibiotics show roughly the same magnitude of efficacy. If antibiotic prophylaxis and growth factors are combined, it can be assumed from network analyses that efficacy of both strategies add to each other [63], so that indications for both these approaches to infection prevention should be considered separately.

P. jirovecii prophylaxis

Prophylaxis with trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole is highly effective for prevention of Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) and is associated with a decrease in mortality [64]. This could be demonstrated in studies with HIV patients, but has also been shown in patients undergoing allogeneic stem cell transplantation or patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) [65]. Green et al. [66] recommend the use of prophylaxis when the risk of PCP is greater than 3.5 %. Unfortunately, the studies included in this meta-analysis are outdated, and data on the actual risk of PCP in a broad range of hematological malignancies such as acute myeloid leukemia are sparse [65]. Generally, because of more intensive therapy and the use of newer protocols such as T-cell-depleting substances, an increased incidence can be assumed. In addition, patients with hematological malignancies appear to have a higher risk of mortality once they develop a PCP [67]. Thus, prophylaxis is recommended for patients deemed at significant risk (Table 5). It should be pointed out that non-neutropenic cancer patients given glucocorticosteroids for prolonged periods of time, typically those with brain metastases from solid tumors or cerebral involvement from non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, carry a substantial risk of PCP and should be candidates for TMP-SMX prophylaxis [68]. In some situations, for example, in patients receiving temozolomide and radiation therapy, the manufacturer recommends additional PCP prophylaxis although the evidence for an increased risk might seem weak. However, in these situations we recommend to follow the advice given by the manufacturer.

The drug of first choice for PCP prophylaxis is TMP/SMX (A-I). The efficacy and tolerability of a daily and thrice-weekly administration of 960 mg are comparable [66]. It is recommended to use the drug for the period of treatment-induced immunosuppression or until CD4 cell count increases above 200/μl. Due to a potential stem cell toxicity, it is recommended to begin TMP/SMX after engraftment in patients with stem cell transplantation. In case of intolerance, oral dapsone (100 mg/day), aerosolized pentamidine (300 mg every 4 weeks) or oral atovaquone (at least 1,500 mg/day) may be used [66].

References

Bucaneve G, Micozzi A, Menichetti F, Martino P, Dionisi MS, Martinelli G, Allione B, D’Antonio D, Buelli M, Nosari AM, Cilloni D, Zuffa E, Cantaffa R, Specchia G, Amadori S, Fabbiano F, Deliliers GL, Lauria F, Foà R, Del Favero A, Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche dell’Adulto (GIMEMA) Infection Program (2005) Levofloxacin to prevent bacterial infection in patients with cancer and neutropenia. N Engl J Med 353:977–987

Cometta A, Kern WV, De Bock R, Paesmans M, Vandenbergh M, Crokaert F, Engelhard D, Marchetti O, Akan H, Skoutelis A, Korten V, Vandercam M, Gaya H, Padmos A, Klastersky J, Zinner S, Glauser MP, Calandra T, Viscoli C, International Antimicrobial Therapy Group of the European Organization for Research Treatment of Cancer (2003) Vancomycin versus placebo for treating persistent fever in patients with neutropenic cancer receiving piperacillin–tazobactam monotherapy. Clin Infect Dis 37:382–389

Kish MA (2001) Guide to development of practice guidelines. Clin Infect Dis 32:851–854

Sandherr M, Einsele H, Hebart H, Kahl C, Kern W, Kiehl M, Massenkeil G, Penack O, Schiel X, Schuettrumpf S, Ullmann AJ, Cornely OA, Infectious Diseases Working Party, German Society for Hematology and Oncology (2006) Antiviral prophylaxis in patients with haematological malignancies and solid tumours: guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Working Party (AGIHO) of the German Society for Hematology and Oncology (DGHO). Ann Oncol 17:1051–1059

Cornely OA, Böhme A, Buchheidt D, Einsele H, Heinz WJ, Karthaus M, Krause SW, Krüger W, Maschmeyer G, Penack O, Ritter J, Ruhnke M, Sandherr M, Sieniawski M, Vehreschild JJ, Wolf HH, Ullmann AJ (2009) Primary prophylaxis of invasive fungal infections in patients with hematologic malignancies. Recommendations of the Infectious Diseases Working Party of the German Society for Haematology and Oncology. Haematologica 94:113–122

Einsele H, Bertz H, Beyer J, Kiehl MG, Runde V, Kolb HJ, Holler E, Beck R, Schwerdfeger R, Schumacher U, Hebart H, Martin H, Kienast J, Ullmann AJ, Maschmeyer G, Krüger W, Niederwieser D, Link H, Schmidt CA, Oettle H, Klingebiel T, Infectious Diseases Working Party (AGIHO) of the German Society of Hematology and Oncology (DGHO) (2003) Infectious complications after allogeneic stem cell transplantation: epidemiology and interventional therapy strategies—guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Working Party (AGIHO) of the German Society of Hematology and Oncology (DGHO). Ann Hematol 82:175–185

Bodey GP, Buckley M, Sathe YS, Freireich EJ (1966) Quantitative relationships between circulating leukocytes and infection in patients with acute leukemia. Ann Intern Med 64:328–340

Klastersky J, Paesmans M, Rubenstein EB, Boyer M, Elting L, Feld R, Gallagher J, Herrstedt J, Rapoport B, Rolston K, Talcott J (2000) The Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer risk index: a multinational scoring system for identifying low-risk febrile neutropenic cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 18:3038–3051

Link H, Böhme A, Cornely OA, Höffken K, Kellner O, Kern WV, Mahlberg R, Maschmeyer G, Nowrousian MR, Ostermann H, Ruhnke M, Sezer O, Schiel X, Wilhelm M, Auner HW, Diseases Working Party (AGIHO) of the German Society of Hematology and Oncology (DGHO); Group Interventional Therapy of Unexplained Fever, Arbeitsgemeinschaft Supportivmassnahmen in der Onkologie (ASO) of the Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft (DKG-German Cancer Society) (2003) Antimicrobial therapy of unexplained fever in neutropenic patients—guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Working Party (AGIHO) of the German Society of Hematology and Oncology (DGHO), Study Group Interventional Therapy of Unexplained Fever, Arbeitsgemeinschaft Supportivmassnahmen in der Onkologie (ASO) of the Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft (DKG-German Cancer Society). Ann Hematol 82:105–117

Freifeld AG, Bow EJ, Sepkowitz KA, Boeckh MJ, Ito JI, Mullen CA, Raad II, Rolston KV, Young JA, Wingard JR, Infectious Diseases Society of America (2011) Clinical practice guideline for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 52:56–93. doi:10.1093/cid/cir073

Slavin MA, Lingaratnam S, Mileshkin L, Booth DL, Cain MJ, Ritchie DS, Wei A, Thursky KA, Australian Consensus Guidelines 2011 Steering Committee (2011) Use of antibacterial prophylaxis for patients with neutropenia. Australian Consensus Guidelines 2011 Steering Committee. Intern Med J 41:102–109. doi:10.1111/j.1445-5994.2010.02341.x

Cullen M, Steven N, Billingham L, Gaunt C, Hastings M, Simmonds P, Stuart N, Rea D, Bower M, Fernando I, Huddart R, Gollins S, Stanley A (2005) Simple Investigation in Neutropenic Individuals of the Frequency of Infection after Chemotherapy +/− Antibiotic in a Number of Tumours (SIGNIFICANT) Trial Group. Antibacterial prophylaxis after chemotherapy for solid tumors and lymphomas. N Engl J Med 353:988–998

Morrison VA (2009) Infectious complications in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: pathogenesis, spectrum of infection, and approaches to prophylaxis. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma 9:365–370

Nucci M, Anaissie E (2009) Infections in patients with multiple myeloma in the era of high-dose therapy and novel agents. Clin Infect Dis 49:1211–1225

Cullen MH, Billingham LJ, Gaunt CH, Steven NM (2007) Rational selection of patients for antibacterial prophylaxis after chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 25:4821–4828

Talcott JA, Siegel RD, Finberg R, Goldman L (1992) Risk assessment in cancer patients with fever and neutropenia: a prospective, two-center validation of a prediction rule. J Clin Oncol 10:316–322

Weissinger F, Auner HW, Bertz H, Buchheidt D, Cornely OA, Egerer G, Heinz W, Karthaus M, Kiehl M, Krüger W, Penack O, Reuter S, Ruhnke M, Sandherr M, Salwender HJ, Ullmann AJ, Waldschmidt DT, Wolf HH (2012) Antimicrobial therapy of febrile complications after high-dose chemotherapy and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation—guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Working Party (AGIHO) of the German Society of Hematology and Oncology (DGHO). Ann Hematol 8:1161–1174. doi:10.1007/s00277-012-1456-8

Kelesidis T, Daikos G, Boumpas D, Tsiodras S (2011) Does rituximab increase the incidence of infectious complications? A narrative review. Int J Infect Dis 15:e2–e16. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2010.03.025

Aksoy S, Harputluoglu H, Kilickap S, Dede DS, Dizdar O, Altundag K, Barista I (2007) Rituximab-related viral infections in lymphoma patients. Leuk Lymphoma 48:1307–1312

Martin SI, Marty FM, Fiumara K, Treon SP, Gribben JG, Baden LR (2006) Infectious complications associated with alemtuzumab use for lymphoproliferative disorders. Clin Infect Dis 43:16–24

Thursky KA, Worth LJ, Seymour JF, Miles Prince H, Slavin MA (2006) Spectrum of infection, risk and recommendations for prophylaxis and screening among patients with lymphoproliferative disorders treated with alemtuzumab. Br J Haematol 132:3–12

Lanini S, Molloy AC, Fine PE, Prentice AG, Ippolito G, Kibbler CC (2011) Risk of infection in patients with lymphoma receiving rituximab: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med 9:36. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-9-36

Pfreundschuh M, Trümper L, Osterborg A, Pettengell R, Trneny M, Imrie K, Ma D, Gill D, Walewski J, Zinzani PL, Stahel R, Kvaloy S, Shpilberg O, Jaeger U, Hansen M, Lehtinen T, López-Guillermo A, Corrado C, Scheliga A, Milpied N, Mendila M, Rashford M, Kuhnt E, Loeffler M, MabThera International Trial Group (2006) CHOP-like chemotherapy plus rituximab versus CHOP-like chemotherapy alone in young patients with good-prognosis diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: a randomised controlled trial by the MabThera International Trial (MInT) Group. Lancet Oncol 7:379–391

Habermann TM, Weller EA, Morrison VA, Gascoyne RD, Cassileth PA, Cohn JB, Dakhil SR, Woda B, Fisher RI, Peterson BA, Horning SJ (2006) Rituximab-CHOP versus CHOP alone or with maintenance rituximab in older patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 24:3121–3127

Hiddemann W, Kneba M, Dreyling M, Schmitz N, Lengfelder E, Schmits R, Reiser M, Metzner B, Harder H, Hegewisch-Becker S, Fischer T, Kropff M, Reis HE, Freund M, Wörmann B, Fuchs R, Planker M, Schimke J, Eimermacher H, Trümper L, Aldaoud A, Parwaresch R, Unterhalt M (2005) Frontline therapy with rituximab added to the combination of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) significantly improves the outcome for patients with advanced-stage follicular lymphoma compared with therapy with CHOP alone: results of a prospective randomized study of the German Low-Grade Lymphoma Study Group. Blood 106:3725–3732

Hallek M, Fischer K, Fingerle-Rowson G, Fink AM, Busch R, Mayer J, Hensel M, Hopfinger G, Hess G, von Grünhagen U, Bergmann M, Catalano J, Zinzani PL, Caligaris-Cappio F, Seymour JF, Berrebi A, Jäger U, Cazin B, Trneny M, Westermann A, Wendtner CM, Eichhorst BF, Staib P, Bühler A, Winkler D, Zenz T, Böttcher S, Ritgen M, Mendila M, Kneba M, Döhner H, Stilgenbauer S, International Group of Investigators; German Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia Study Group (2010) Addition of rituximab to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 376:1164–1174. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61381-5

Pizzo PA (1993) Management of fever in patients with cancer and treatment-induced neutropenia. N Engl J Med 328:1323–1332

Madani TA (2000) Clinical infections and bloodstream isolates associated with fever in patients undergoing chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia. Infection 28:367–373

Gudiol C, Bodro M, Simonetti A, Tubau F, González-Barca E, Cisnal M, Domingo-Domenech E, Jiménez L, Carratalà J (2012) Changing aetiology, clinical features, antimicrobial resistance, and outcomes of bloodstream infection in neutropenic cancer patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03879.x

Cherif H, Kronvall G, Björkholm M, Kalin M (2003) Bacteraemia in hospitalised patients with malignant blood disorders: a retrospective study of causative agents and their resistance profiles during a 14-year period without antibacterial prophylaxis. Hematol J 4:420–426

Wisplinghoff H, Seifert H, Wenzel RP, Edmond MB (2003) Current trends in the epidemiology of nosocomial bloodstream infections in patients with hematological malignancies and solid neoplasms in hospitals in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 36:1103–1110

Legrand M, Max A, Peigne V, Mariotte E, Canet E, Debrumetz A, Lemiale V, Seguin A, Darmon M, Schlemmer B, Azoulay E (2012) Survival in neutropenic patients with severe sepsis or septic shock. Crit Care Med 40:43–49. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e31822b50c2

Marchetti O, Calandra T (2002) Infections in neutropenic cancer patients. Lancet 359:723–725

Schiel X, Link H, Maschmeyer G, Glass B, Cornely OA, Buchheidt D, Wilhelm M, Silling G, Helmerking M, Hiddemann W, Ostermann H, Hentrich M (2006) A prospective, randomized multicenter trial of the empirical addition of antifungal therapy for febrile neutropenic cancer patients: results of the Paul Ehrlich Society for Chemotherapy (PEG) Multicenter Trial II. Infection 34:118–126

Safdar A, Rodriguez GH, Balakrishnan M, Tarrand JJ, Rolston KV (2006) Changing trends in etiology of bacteremia in patients with cancer. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 25:522–526

Velasco E, Byington R, Martins CS, Schirmer M, Dias LC, Gonçalves VM (2004) Bloodstream infection surveillance in a cancer centre: a prospective look at clinical microbiology aspects. Clin Microbiol Infect 10:542–549

Gafter-Gvili A, Fraser A, Paul M, Vidal L, Lawrie TA, van de Wetering MD, Kremer LC, Leibovici L (2012) Antibiotic prophylaxis for bacterial infections in afebrile neutropenic patients following chemotherapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1:CD004386. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004386

Imran H, Tleyjeh IM, Arndt CA, Baddour LM, Erwin PJ, Tsigrelis C, Kabbara N, Montori VM (2008) Fluoroquinolone prophylaxis in patients with neutropenia: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 27:53–63

Leibovici L, Paul M, Cullen M, Bucaneve G, Gafter-Gvili A, Fraser A, Kern WV (2006) Antibiotic prophylaxis in neutropenic patients: new evidence, practical decisions. Cancer 107:1743–1751

Bow EJ, Rayner E, Louie TJ (1988) Comparison of norfloxacin with cotrimoxazole for infection prophylaxis in acute leukemia. The trade-off for reduced gram-negative sepsis. Am J Med 84:847–854

Dekker AW, Rozenberg-Arska M, Verhoef J (1987) Infection prophylaxis in acute leukemia: a comparison of ciprofloxacin with trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole and colistin. Ann Intern Med 106:7–11

Donnelly JP, Maschmeyer G, Daenen S (1992) Selective oral antimicrobial prophylaxis for the prevention of infection in acute leukaemia-ciprofloxacin versus co-trimoxazole plus colistin. The EORTC-Gnotobiotic Project Group. Eur J Cancer 28A:873–878

von Baum H, Sigge A, Bommer M, Kern WV, Marre R, Döhner H, Kern P, Reuter S (2006) Moxifloxacin prophylaxis in neutropenic patients. J Antimicrob Chemother 58:891–894

Vehreschild JJ, Moritz G, Vehreschild MJ, Arenz D, Mahne M, Bredenfeld H, Chemnitz J, Klein F, Cremer B, Böll B, Kaul I, Wassmer G, Hallek M, Scheid C, Cornely OA (2012) Efficacy and safety of moxifloxacin as antibacterial prophylaxis for patients receiving autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a randomised trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents 39:130–134

Tjan-Heijnen VC, Postmus PE, Ardizzoni A, Manegold CH, Burghouts J, van Meerbeeck J, Gans S, Mollers M, Buchholz E, Biesma B, Legrand C, Debruyne C, Giaccone G, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer–Lung Cancer Group (2001) Reduction of chemotherapy-induced febrile leucopenia by prophylactic use of ciprofloxacin and roxithromycin in small-cell lung cancer patients: an EORTC double-blind placebo-controlled phase III study. Ann Oncol 12:1359–1368

Cruciani M, Malena M, Bosco O, Nardi S, Serpelloni G, Mengoli C (2003) Reappraisal with meta-analysis of the addition of Gram-positive prophylaxis to fluoroquinolone in neutropenic patients. J Clin Oncol 21:4127–4137

Gafter-Gvili A, Fraser A, Paul M, Leibovici L (2005) Meta-analysis: antibiotic prophylaxis reduces mortality in neutropenic patients. Ann Intern Med 142:979–995

Lambert ML, Suetens C, Savey A, Palomar M, Hiesmayr M, Morales I, Agodi A, Frank U, Mertens K, Schumacher M, Wolkewitz M (2011) Clinical outcomes of health-care-associated infections and antimicrobial resistance in patients admitted to European intensive-care units: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 11:30–38. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70258-9

de Kraker ME, Wolkewitz M, Davey PG, Koller W, Berger J, Nagler J, Icket C, Kalenic S, Horvatic J, Seifert H, Kaasch AJ, Paniara O, Argyropoulou A, Bompola M, Smyth E, Skally M, Raglio A, Dumpis U, Kelmere AM, Borg M, Xuereb D, Ghita MC, Noble M, Kolman J, Grabljevec S, Turner D, Lansbury L, Grundmann H, BURDEN Study Group (2011) Clinical impact of antimicrobial resistance in European hospitals: excess mortality and length of hospital stay related to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:1598–1605. doi:10.1128/AAC.01157-10

de Kraker ME, Wolkewitz M, Davey PG, Koller W, Berger J, Nagler J, Icket C, Kalenic S, Horvatic J, Seifert H, Kaasch A, Paniara O, Argyropoulou A, Bompola M, Smyth E, Skally M, Raglio A, Dumpis U, Melbarde Kelmere A, Borg M, Xuereb D, Ghita MC, Noble M, Kolman J, Grabljevec S, Turner D, Lansbury L, Grundmann H (2011) Burden of antimicrobial resistance in European hospitals: excess mortality and length of hospital stay associated with bloodstream infections due to Escherichia coli resistant to third-generation cephalosporins. J Antimicrob Chemother 66:398–407. doi:10.1093/jac/dkq412

Rangaraj G, Granwehr BP, Jiang Y, Hachem R, Raad I (2010) Perils of quinolone exposure in cancer patients: breakthrough bacteremia with multidrug-resistant organisms. Cancer 116:967–973. doi:10.1002/cncr.24812

Kern WV, Klose K, Jellen-Ritter AS, Oethinger M, Bohnert J, Kern P, Reuter S, von Baum H, Marre R (2005) Fluoroquinolone resistance of Escherichia coli at a cancer center: epidemiologic evolution and effects of discontinuing prophylactic fluoroquinolone use in neutropenic patients with leukemia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 24:111–118

Gafter-Gvili A, Paul M, Fraser A, Leibovici L (2007) Effect of quinolone prophylaxis in afebrile neutropenic patients on microbial resistance: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother 59:5–22

Chong Y, Yakushiji H, Ito Y, Kamimura T (2011) Clinical impact of fluoroquinolone prophylaxis in neutropenic patients with hematological malignancies. Int J Infect Dis 15:e277–e281. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2010.12.010

Guthrie KA, Yong M, Frieze D, Corey L, Fredricks DN (2010) The impact of a change in antibacterial prophylaxis from ceftazidime to levofloxacin in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 45:675–681. doi:10.1038/bmt.2009.216

Lew MA, Kehoe K, Ritz J, Antman KH, Nadler L, Kalish LA, Finberg R (1995) Ciprofloxacin versus trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole for prophylaxis of bacterial infections in bone marrow transplant recipients: a randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 13:239–250

Reuter S, Kern WV, Sigge A, Döhner H, Marre R, Kern P, von Baum H (2005) Impact of fluoroquinolone prophylaxis on reduced infection-related mortality among patients with neutropenia and hematologic malignancies. Clin Infect Dis 40:1087–1093

Ng ES, Liew Y, Earnest A, Koh LP, Lim SW, Hsu LY (2011) Audit of fluoroquinolone prophylaxis against chemotherapy-induced febrile neutropenia in a hospital with highly prevalent fluoroquinolone resistance. Leuk Lymphoma 52:131–133. doi:10.3109/10428194.2010.518655

Bow EJ (2011) Fluoroquinolones, antimicrobial resistance and neutropenic cancer patients. Curr Opin Infect Dis 24:545–553. doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e32834cf054

Smith TJ, Khatcheressian J, Lyman GH, Ozer H, Armitage JO, Balducci L, Bennett CL, Cantor SB, Crawford J, Cross SJ, Demetri G, Desch CE, Pizzo PA, Schiffer CA, Schwartzberg L, Somerfield MR, Somlo G, Wade JC, Wade JL, Winn RJ, Wozniak AJ, Wolff AC (2006) 2006 update of recommendations for the use of white blood cell growth factors: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol 24:3187–3205

Aapro MS, Bohlius J, Cameron DA, Dal Lago L, Donnelly JP, Kearney N, Lyman GH, Pettengell R, Tjan-Heijnen VC, Walewski J, Weber DC, Zielinski C, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (2011) 2010 update of EORTC guidelines for the use of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor to reduce the incidence of chemotherapy-induced febrile neutropenia in adult patients with lymphoproliferative disorders and solid tumours. Eur J Cancer 47:8–32. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2010.10.013

Crawford J, Allen J, Armitage J, Blayney DW, Cataland SR, Heaney ML, Htoy S, Hudock S, Kloth DD, Kuter DJ, Lyman GH, McMahon B, Steensma DP, Vadhan-Raj S, Westervelt P, Westmoreland M, National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2011) Myeloid growth factors. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 9:914–932

Herbst C, Naumann F, Kruse EB, Monsef I, Bohlius J, Schulz H, Engert A (2009) Prophylactic antibiotics or G-CSF for the prevention of infections and improvement of survival in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1:CD007107. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007107

Sepkowitz KA (1992) Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia among patients with neoplastic disease. Semin Respir Infect 7:114–121

Pagano L, Fianchi L, Mele L, Girmenia C, Offidani M, Ricci P, Mitra ME, Picardi M, Caramatti C, Piccaluga P, Nosari A, Buelli M, Allione B, Cortelezzi A, Fabbiano F, Milone G, Invernizzi R, Martino B, Masini L, Todeschini G, Cappucci MA, Russo D, Corvatta L, Martino P, Del Favero A (2002) Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients with malignant haematological diseases: 10 years’ experience of infection in GIMEMA centres. Br J Haematol 117:379–386

Green H, Paul M, Vidal L, Leibovici L (2007) Prophylaxis of Pneumocystis pneumonia in immunocompromised non-HIV-infected patients: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Mayo Clin Proc 82:1052–1059

Green H, Paul M, Vidal L, Leibovici L (2007) Prophylaxis for Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) in non-HIV immunocompromised patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3:CD005590

Sepkowitz KA, Brown AE, Telzak EE, Gottlieb S, Armstrong D (1992) Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia among patients without AIDS at a cancer hospital. JAMA 267:832–837

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Neumann, S., Krause, S.W., Maschmeyer, G. et al. Primary prophylaxis of bacterial infections and Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients with hematological malignancies and solid tumors. Ann Hematol 92, 433–442 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-013-1698-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-013-1698-0