Abstract

Purpose

There have been few case reports describing cystic duct stent insertion in the management of acute cholecystitis secondary to benign disease with no case series published to date. We present our series demonstrating the role of cystic duct stents in managing benign gallbladder disease in those patients unfit for surgery.

Materials and Methods

Thirty three patients unfit for surgery in our institution underwent cystic duct stent insertion for the management of acute cholecystitis in the period June 2008 to June 2013. Patients underwent a mixture of transperitoneal and transhepatic gallbladder puncture. The cystic duct was cannulated with a hydrophilic guidewire which was subsequently passed through the common bile duct and into the duodenum. An 8Fr 12-cm double-pigtail stent was placed with the distal end lying within the duodenum and the proximal end within the gallbladder.

Results

Ten patients presented with gallbladder perforation, 21 patients with acute cholecystitis, 1 with acute cholangitis and 1 with necrotising pancreatitis. The technical success rate was 91 %. We experienced a 13 % complication rate with 3 % mortality rate at 30 days.

Conclusion

Cystic duct stent insertion can be successfully used to manage acute cholecystitis, gallbladder empyema or gallbladder perforations in those unfit for surgery and should be considered alongside external gallbladder drainage as a definitive mid-term treatment option.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is widely recognised as the gold-standard treatment for patients presenting with acute cholecystitis [1]. Many surgeons favour operating on a “hot” gallbladder within 72 h of presentation to avoid the subsequent development of adhesions and making delayed surgery more difficult [2]. A meta-analysis by Siddiqui et al. [3] suggests that early laparoscopic cholecystectomy allows significantly shorter total hospital stay with no significant differences in conversion rates or complications. This is at the cost of a significantly longer operation time.

Some of these patients present an anaesthetic risk or are too unwell to undergo urgent surgery. In these cases, cholecystostomy provides a minimally invasive alternative. In addition, a number of these unfit patients will never undergo surgery due to their severe comorbidities. This group is faced with the risk of recurrent cholecystitis once the drain is removed or the prospect of a long-term external drainage. Ha et al. [4] found that those patients presenting with acute cholecystitis who were managed by temporary percutaneous cholecystostomy, but did not proceed to cholecystectomy, experienced a 1-year and 3-year recurrence of acute cholecystitis of 35 and 46 %, respectively. It is these patients that provide a management challenge as they are often elderly or infirm and therefore find long-term percutaneous drainage difficult. Cystic duct stent insertion therefore provides an alternative for these patients, and we present a case series of patient undergoing this novel new therapy.

Materials and Methods

The clinical history and imaging studies of 33 patients undergoing cystic duct stent insertion were retrospectively studied. During the period June 2008 to July 2013, all patients at our institution with an acute presentation of stone disease who were unfit for surgery were considered for cystic duct stent insertion. All cases were discussed at a clinical multidisciplinary meeting prior to undergoing stenting of the cystic duct. Informed consent was obtained from all patients in this study.

The initial stage was to insert a percutaneous cholecystostomy under ultrasound guidance via either a transhepatic or transperitoneal route. This allowed resolution of the acute episode. To avoid long-term external drainage, patients then returned for an elective insertion of a cystic duct stent.

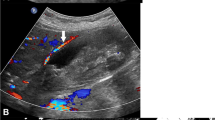

An initial contrast study was performed to assess the biliary tree, in particular, the cystic duct (Fig. 1). We continued to attempt cystic duct stent insertion both in those with a blocked cystic duct and in those demonstrating free flow of contrast into the duodenum. A standard wire (PTFE Coated Guidewire (Fixed Core) 3 cm Flexible tip 0.035″ × 150 cm, Boston Scientific) was passed through the existing drainage tube which was then exchanged for an 8Fr sheath (BRITE TIP® Interventional Sheath, Cordis). Through this, a 4Fr straight catheter (TEMPO™ straight 4Fr 65 cm length, Cordis) and a hydrophilic wire (Radiofocus® Guidewire M standard type 0.035″ 150 cm length, Terumo) were passed and negotiated down the cystic duct under fluoroscopic guidance. Once the wire and catheter had been manipulated into the duodenum (Fig. 2), the hydrophilic wire was exchanged for a stiff wire (Amplatz Super Stiff™ Guidewire 3 mm J-Tip 0.035″ × 145 cm length, Boston Scientific). Over this, double-pigtail stent (Renal transplantation ureteral stent (OptiSoft) 8Fr 12 cm, Optimed) was inserted. There are sideholes along the length of and at either end of the stent. The two pigtail ends of the stent were positioned in the gallbladder and the duodenum, respectively (Fig. 3). A covering external non locking gallbladder drain was left in situ. This allowed time to ensure that the internal stent was effective and also provided access for a cholangiogram prior to removal of the external drain. A cholangiogram was performed 48–72 h after insertion (Fig. 4) to ensure that the internal cystic duct stent is working. If there is good flow and drainage internally, the external GB drain was removed.

An 8Fr 12-cm double-pigtail stent (Optimed transplant ureteral stent) is inserted over a standard amplatz wire. The ends of the stent are positioned within the gallbladder proximally and the third part of the duodenum distally. Following deployment of the stent, a standard amplatz wire is passed through the sheath into the gallbladder. A covering 8Fr external cholecystostomy drainage catheter is positioned over this guidewire, using fluoroscopic guidance to position the pigtail separate to the stent

We present the patient demographics of this group along with the technical success of the procedure, which was defined as successful insertion of a cystic duct stent. The complications are analysed, and we discuss the lessons we have learned from our case series.

Results

Patient Demographics

During the period June 2008 to July 2013, all patients at our institution with an acute presentation of stone disease who were unfit for surgery were considered for cystic duct stent insertion. A total of 33 patients underwent attempted stent insertion. The median age or our patient group was 75 years (range 43–96). The female to male ratio was 45:55 %. Of these patients, 30 % (n = 10) presented with gallbladder perforation and 64 % (n = 21) with acute cholecystitis. One patient presented with necrotising pancreatitis (3 %) and one patient with acute cholangitis (3 %).

The route of percutaneous cholecystostomy puncture was transhepatic in 88 % (n = 29) and transperitoneal in 12 % (n = 4). The median interval between cholecystostomy and cystic duct stent insertion was 9 days (range 0–180 days). Table 1 lists the most relevant features of the patients and their stents including follow-up. Additionally, Fig. 5 consort diagram demonstrates the patient flow at our institution.

Technical Success

Our technical success rate was 91 %. There were 3 technical failures from the series of 33 patients. In 2 of the 3 cases, the cystic duct was extremely tortuous, and we could not manipulate a wire through the duct. One of these patients died of biliary sepsis 12 days following attempted stent insertion. The second patient died 8 months later of metastatic gastric carcinoma. This diagnosis was not known at the time of cholecystostomy; the patient presented with acute cholecystitis and not obstructive jaundice. In the third case, there was a stricture of the common bile duct secondary to pancreatitis, and it was only possible to place an internal external drain. A metal stent was placed 13 days later via a retrograde endoscopic approach.

Follow-up

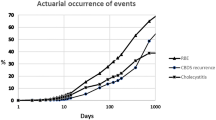

Patients were followed up for a median of 11.6 months (range of 1–76 months). In 73 % (n = 22) of patients the stent remained in situ at the time of follow-up/death. 20 % of the patients (n = 6) became well enough to undergo subsequent cholecystectomy. The stent was seen to migrate in 2 patients (7 %).

Complications

The patient group was followed up for a median of 11.6 months (range 1–76 months) by the surgical team. 3 of the 30 technically successful procedures (10 %) experienced complications, all of which were at 30 days.

Complications at 30 days

The first case to undergo cystic duct stent insertion was not left with a covering external cholecystostomy drain. This patient went on to develop an abdominal wall collection post procedure and was part of the reasoning behind the subsequent practice of a covering external drain for a short post procedural period.

Case 29 represented 6 weeks following stent insertion with recurrent cholecystitis. Imaging at this time demonstrated the absence of the stent, and the patient was presumed to have passed the stent per rectum.

In case 18, the patient presented 13 months post procedure with acute small bowel obstruction. Abdominal radiograph demonstrated migration of the cystic duct stent; however, a subsequent CT scan of the abdomen confirmed gallstone ileus as the cause of obstruction.

Technical Procedural Notes

One patient demonstrated inadequate drainage of contrast to the duodenum on the post procedural cholangiogram. In this case, the patient underwent a second cystic duct stent insertion which was positioned adjacent to the first stent. This led to a satisfactory result on a further cholangiogram, and the external drain was removed with no further complication.

In two further cases, two attempts were required to insert a stent. In case 16, a plastic stent was successfully positioned on the second attempt. In case 27, a metal stent was successfully placed as it was not possible to advance a plastic stent, despite dilatation, due to a tight stricture in the cystic duct.

Lessons Learnt

Our experience has taught us a number of lessons about cystic duct stent insertion, and below are a few tips from our own learning curve:

Firstly, the stent can migrate. This is described above in the complications section.

Secondly, the stents can be removed at the time of surgery should this become a possibility. In case 26, the patient became well enough to undergo laparoscopic cholecystectomy 2 months following cystic duct stent insertion. The stent was milked into the common bile duct at the time of surgery and successfully removed endoscopically.

Thirdly, a covering external gallbladder drain is essential. This not only allows access for follow-up cholangiograms but also provides external drainage should the stent fail to alleviate the obstruction.

Fourthly, the cystic duct can be very tortuous and sometimes stenosed or occluded. The conclusion we draw from this is that those patients in whom the cystic duct is either markedly tortuous or not clearly delineated on the initial cholangiogram are less likely to undergo a successful procedure. This is also true for patients with a demonstrable cystic duct stenosis/occlusion. In this group, we suggest that cystic duct stent insertion should be avoided or delayed.

Discussion

Acute cholecystitis is a common surgical emergency. Although laparoscopic cholecystectomy is well established as the treatment option of choice, our ageing populations are increasingly developing these conditions with increased comorbidities precluding early operative management. In these cases, cholecystostomy is recognised to be the best course of action. This can be as a temporary measure to allow the patient to recover from the acute episode and then undergo an elective cholecystectomy [5]. Some patients will never be fit enough to undergo surgery and for them cholecystostomy can be the definitive treatment [6]. Little et al. [7] suggest 3-monthly catheter exchanges are needed in these patients. However, the disadvantages of long-term drainage catheters are clear. Learning to manage a drainage bag can be challenging, particularly for the elderly. External drainage catheters are prone to dislodgement, at risk of infection and can be uncomfortable. In addition, routine catheter exchange is required to prevent obstruction. Cystic duct stent insertion provides an alternative treatment option for these patients.

Gatenby et al. [8] describe a single case report of percutaneous transhepatic cholecystoduodenal stent insertion for a case of gallbladder empyema. In this case, the patient would not agree to operative management, and an internal stent allowed the patient to be catheter free. There are reports in the literature of cystic duct stent insertion for patients with malignant obstruction of the cystic duct. Sheiman et al. [9] describe the use of a metallic cystic duct stent to relieve obstruction caused by stenting of the common bile duct for malignant disease. There is a single case report by Comin et al. [10] of a patient undergoing cystic duct stent insertion for stone disease. To date, there are no case series documenting the use of cystic duct stents to manage benign GB disease.

We believe that patients facing the prospect of long-term cholecystostomy catheters should be given the option of internalisation of their drain via the cystic duct. In our series, we have demonstrated the procedure to be technically feasible with a high rate of technical success (91 %). Our 30 day complication rate is 10 %. Other than the cases of stent migration, all of the complications and technical failures have occurred in patients with tortuous or non-opacifying/occluded cystic ducts. Outside the scope of this case series, we have had some success following a delayed interval in patients with an obstructed cystic duct. With this in mind, we would suggest repeating the cholangiogram with a 4-week interval to reassess the cystic duct for stent feasibility.

Once inserted, the stent can be left in situ indefinitely. If the patient becomes well enough to undergo surgery at a later date the stent can be removed at the time of cholecystectomy. Endoscopic removal should not be required unless there is evidence of stent migration, which we have demonstrated can occur. A biliary stent could also be used. The advantages of the ureteric stent are holes along the length of the stent, manageable length of delivery system if working single handed and being able to deliver over a 0.035″ wire.

Some procedural modifications have been employed during our learning experience of this technique. As outlined in the technical procedural notes section above, a second adjacent plastic stent can aid drainage into the duodenum. In addition, a metal stent can be considered if a plastic stent will not advance over the guidewire due to duct stricturing.

The benefit of a covering external drain was demonstrated by our first case where the patient developed a superficial collection following drain removal. As our experience has increased, we have moved to leaving the external drain in situ for 4–6 weeks in those patients who underwent initial percutaneous cholecystostomy via the transperitoneal route. This allows track maturation to occur in a similar manner to the track formed by T-tubes and thereby reduce the risk of potential collection formation.

The tendency of the access sheath to back out of the gallbladder was also noted, resulting in the loss of position in a number of cases. An assistant to steady the sheath during the procedure, or suturing the sheath to the skin, eliminated this problem. We have not employed a microcatheter as yet, but potentially for those cystic ducts that we cannot negotiate a microcatheter may assist.

In conclusion, cystic duct stent placement is a simple and effective method for managing acute presentations of stone disease in patients unfit for surgery. We have shown it to be a definitive treatment option in this group with a low major complication rate and high technical success rates. In addition, in those patients that become fit for surgery at a later date, the cystic duct stent insertion has provided a useful bridge to laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

References

Shea JA, Healey MJ, Berlin JA, Clarke JR, Malet PF, Staroscik RN, Schwartz JS, Williams SV (1996) Mortality and complications associated with laparoscopic cholecystectomy. A meta-analysis. Ann Surg 224(5):609–620

Lo CM, Liu CL, Fan ST, Lai EC, Wong J (1998) Prospective randomized study of early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Ann Surg 227(4):461–467

Siddiqui T, MacDonald A, Chong PS, Jenkins JT (2008) Early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Am J Surg 195(1):40–47

Ha JP, Tsui KK, Tang CN, Siu WT, Fung KH, Li MK (2008) Cholecystectomy or not after percutaneous cholecystostomy for acute calculous cholecystitis in high-risk patients. Hepatogastroenterology 55(86–87):1497–1502

Akyurek N, Salman B, Yuksel O, Tezcaner T, Irkorucu O, Yucel C, Oktar S, Tatlicioglu E (2005) Management of acute calculous cholecystitis in high-risk patients: percutaneous cholecystotomy followed by early laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 15(6):315–320

Berger H, Pratschke E, Arbogast H, Stabler A (1989) Percutaneous cholecystostomy in acute acalculous cholecystitis. Hepatogastroenterology 36(5):346–348

Little MW, Briggs JH, Tapping CR, Bratby MJ, Anthony S, Phillips-Hughes J, Uberoi R (2013) Percutaneous cholecystostomy: the radiologist’s role in treating acute cholecystitis. Clin Radiol 68(7):654–660

Gatenby P, Flook M, Spalding D, Tait P (2009) Percutaneous transhepatic cholecystoduodenal stent for empyema of the gallbladder. Br J Radiol 82(978):e108–e110

Sheiman RG, Stuart K (2004) Percutaneous cystic duct stent placement for the treatment of acute cholecystitis resulting from common bile duct stent placement for malignant obstruction. J Vasc Interv Radiol 15(9):999–1001

Comin JM, Cade RJ, Little AF (2010) Percutaneous cystic duct stent placement in the treatment of acute cholecystitis. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol 54(5):457–461

Conflict of Interest

Dr N Hersey, Dr S D Goode, Dr R Peck and Dr F Lee declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights

Ethical approval for this type of study formal consent is not required.

Statement of Informed Consent

All the patients involved in the study did have informed consent.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hersey, N., Goode, S.D., Peck, R.J. et al. Stenting of the Cystic Duct in Benign Disease: A Definitive Treatment for the Elderly and Unwell. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 38, 964–970 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-014-1014-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-014-1014-y