Abstract

Purpose

Management of the unexplained, painful large diameter metal-on-metal (MOM) hip replacement is difficult. Although there are guidelines for surgeons, there is no clear documented evidence describing the overall threshold for revision surgery. The 2010 product recall of the DePuy Articular Surface Replacement (ASR) and subsequent media coverage may have increased patient and surgeon apprehension, resulting in earlier intervention, i.e. at a greater Oxford hip score (OHS) than expected. Our aim was to investigate whether the threshold for revision using known parameters was affected by the ASR recall. These parameters include poor clinical results (persistent pain or mechanical symptoms), pseudotumour or other progressive soft tissue involvement, osteolysis and high or rising metal ion levels.

Methods

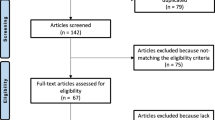

We used our national referral database of MOM hips, which were revised between 2008 and 2012. Once inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied, we identified 240 patients—71 patients in the pre-recall group and 169 patients in the post-recall group.

Results

The ASR product recall did not seem to affect the threshold for revision of a MOM hip, with no significant difference between the two groups in terms of the functional (median OHS = 17 pre-recall and 20 post-recall; p = 0.2109) and radiological (median inclination angle = 50 pre-recall and 48 post-recall; p = 0.3221) markers used to guide management. We did however discover that blood metal ion levels were higher in the post-recall group.

Conclusion

Issue of a product recall did not change the hip function threshold for revision surgery. The decision to revise a metal-on-metal hip is complex and should follow published guidelines, encompassing metal ion measurement and cross-sectional imaging where appropriate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The management of the painful large diameter metal-on-metal (MOM) hip replacement is difficult. In addition to clinical symptoms and signs, a surgeon will use serological tests and radiological investigations to assess the risks and benefits of revision surgery. There are guidelines for surgeons [1] which suggest considering revision dependent on the patient’s symptoms, if there is abnormal imaging and/or rising blood metal ion levels. However, there is no clear documented evidence describing the overall threshold for revision surgery.

In all cases, the complete clinical picture should be evaluated before making a decision to revise. In cases with extreme clinical or investigational parameters the decision is relatively straightforward. For example, surgeons would consider revision in cases where: the patient was significantly symptomatic, with an Oxford hip score (OHS) less than 30 (out of 48) and raised blood metal ion levels (>7 ppb) [2, 3]; or if metal artifact reduction sequence (MARS) MRI revealed a large (>10 cm) solid pseudotumour or gross soft tissue damage [1, 4]. Conversely, most would consider non-surgical management in cases where: the patient was asymptomatic, the OHS was greater than 41 out 48; blood metal ion levels were <5 ppb; and MARS MRI revealed no pseudotumour, fluid or muscle abnormalities.

Management of patients with parameters in the “grey” (intermediate) zones or those with unexplained pain can be difficult and psychological factors may also play an important role in such cases. The 2010 product recall of the ASR hip [5, 6] and subsequent media coverage suggesting a public health scare may have increased patient and surgeon apprehension [7], resulting in a lower threshold for hip revision surgery. Our aim was to investigate whether the threshold for revision, using known parameters such as the OHS, was affected by the ASR recall. We hypothesise that intervention was being carried out at a higher OHS following the recall (i.e. a lower threshold).

Materials and methods

We used our national referral database of MOM hips, which were revised between 2008 and 2012. Data collected included age, months to revision, head and cup size (in mm), pre-revision cobalt and chromium levels (in ppb), pre-operative OHS and radiographic inclination angles.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

All patients with an OHS undergoing revision of a MOM hip arthroplasty for unexplained pain were included in the study. We excluded any patients with an incomplete data set and all hips that were revised for a known cause (including infection, fracture, or radiologically confirmed osteolysis and loosening).

Statistical analysis was performed using the Prism statistics program (Prism 5.0a, GraphPad Software Inc, La Jolla, California, USA). The Mann Whitney U-test was used for non-parametric data; Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical data; and the chi-squared test was used to compare proportions. Level of significance was p < 0.05.

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from the Riverside Ethics Committee (COREC 07/Q0401/25).

Results

We identified 285 patients between 2008 and 2012 who fulfilled our inclusion criteria. Of these, 111 were pre-recall and 174 were post-recall. Once exclusion criteria were applied, we produced a final number of 240 patients, of which 71 patients were in the pre-recall group and 169 patients in the post-recall group.

Patient demographics

Pre-recall group

There were 32 males and 39 females in the pre-recall group (Table 1).

The following implants were revised: 26 Smith & Nephew Birmingham hip resurfacings (BHR), 20 Depuy ASR, nine Zimmer Durom, seven Corin Cormet, three Biomet M2a Magnum, two Finsbury Adept and one case each of four other implants. The median OHS was 17 (interquartile range [IQR] = 10–26), and the median inclination angle was 50 (IQR = 45–55). The median age was 56 (IQR = 48–60) with a median time to revision of 33 months (IQR = 18–47). Median head size in this group was 46 mm (IQR = 44–50).

Blood metal ion levels in this group showed a median chromium of 3.4 ppb (IQR = 1.8–7.4) and a median Cobalt of 4.2 ppb (IQR = 1.5–11).

Post-recall group

There were 74 males and 95 females in the post-recall group (Table 2).

The following implants were revised: 42 Smith & Nephew BHR, 60 Depuy ASR, six Zimmer Durom, 28 Corin Cormet, two Biomet M2a Magnum, six Finsbury Adept and 25 others. The median OHS was 20 (IQR = 13–26), and the median inclination angle was 48 (IQR = 42–53). The median age was 56 (IQR = 49–62) with a median time to revision of 50 months (IQR = 36–71). Median head size was 47 mm (IQR = 44–50). Blood metal ion levels in this group showed a median chromium of 5.0 ppb (IQR = 2.2–14) and a median Cobalt of 7.4 ppb (IQR = 3.0–19).

Group comparisons

Prior to the recall, implants were revised earlier (median 33 months pre-recall compared to 50 months post-recall) and this was found to be statistically significant (p < 0.0001). There was no significant difference in head sizes (p = 0.9778) or inclination angles (p = 0.3221) between the two groups. Cobalt ion levels were significantly higher in implants revised post-recall (p = 0.01). Chromium ion levels were also higher in implants revised post-recall, but this was not statistically significant (p = 0.053). The median OHS was 17/48 pre-recall and 20/48 post-recall. This may suggest a slightly lower threshold for clinicians to revise, but this was not statistically significant (p = 0.2109).

The mix of implants was found to be significantly different between the two groups, with p = 0.073 (Graph 1). Notably, there was an increase in the percentage of ASRs being revised as a total of all implants. Prior to the recall, 20 of the 71 implants revised were the ASR (28 %), whereas following the recall this rose to 60 out of 169 (35.5 %).

Discussion

In 2010 there was a worldwide withdrawal from the market of the DePuy ASR metal-on-metal hip replacement system (ASR hip resurfacing and ASR XL THR, DePuy, Warsaw, Indiana, USA) because of higher than expected failure rates [5]. It was, and has been, the focus of much media attention leaving patients understandably concerned [8, 9]. One may expect that, with this fear and dissatisfaction amongst their patients, surgeons might lower their threshold for intervention in these cases. Although there have been previous recalls of failing implantable devices, including other hip prostheses [10, 11] and breast implants [12], the effect on thresholds for intervention following these recalls have never been examined.

Reviewing our results, some of the findings were to be expected. For example, following the ASR recall the percentage of ASR hips being revised (as a percentage of all hips revised) increased significantly (p = 0.0073). Additionally we found that there was no difference between the two groups in terms of implant sizes and positioning—both documented risk factors for a failing MOM implant [13].

The mean OHS pre-recall was 19 (median = 17), while post-recall it was 21 (median = 20). This would suggest that there was a lower threshold to revise post-recall, i.e. hips were being revised at a higher functional level; however, this difference was not statistically significant.

It was interesting to discover that both serum cobalt and chromium ion levels were higher in the post recall group, although only cobalt ion levels were significantly different. This would suggest that following the recall, surgeons were more wary of the risk of failure and more likely to intervene if metal ion levels were abnormal. It would also suggest that elevated blood cobalt levels are a matter of concern, particularly in asymptomatic patients. Cobalt levels greater than 10ug/l are thought to greatly increase the risk of osteolysis, and hence failure of the implant.

Other findings were less predictable. For example, implants were revised earlier pre-recall (at mean 37.75 months) rather than post-recall (mean 55.2 months). This was an unexpected finding and has uncertain clinical relevance. The focus of this study was on the threshold of revision surgery based on hip function rather than time to revision. However, there is emerging evidence to suggest a ‘watchful waiting’ approach for many patients in ‘grey’ categories (such as asymptomatic patients with raised metal ions or pseudotumour) [14].

There are limitations to our study. This is a retrospective study with relatively small cohorts. The decision to proceed with revision hip surgery in these cases is a complex one. There are multiple factors to consider and these cannot all be measured in a standardized way. However recruitment to the study was identical pre- and post-recall in order to reduce selection bias. It should be noted that our findings are limited to the time period we studied (two years either side of the recall). Decision making may have been affected but not within the first few years of the recall.

One may expect a product recall to cause the threshold for intervention to drop and for surgeons to intervene early in any case where there are doubts over the performance or safety of an implant. However, from this data it would appear that MOM hips were actually performing for longer or being revised later.

References

Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Medical Device Alert: MDA/2012/036. http://www.mhra.gov.uk/home/groups/dts-bs/documents/medicaldevicealert/con155767.pdf. Accessed 9 May 2014

Hart AJ, Skinner JA, Winship P et al (2009) Circulating levels of cobalt and chromium from metal-on-metal hip replacement are associated with CD8+ T-cell lymphopenia. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 91-B:835–842

Van Der Straeten C, Grammatopoulos G, Gill HS, Calistri A, Campbell P, De Smet KA (2013) The interpretation of metal ion levels in unilateral and bilateral hip resurfacing. Clin Orthop Relat Res 471(2):377–385

Grammatopolous G, Pandit H, Kwon YM et al (2009) Hip resurfacings revised for inflammatory pseudotumour have a poor outcome. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 91-B:1019–1024

MHRA (2010) Medical Device Alert: MDA/2010/069, DePuy ASR hip replacement implants. Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency, London

Krantz N, Miletic B, Migaud H, Girard J (2012) Hip resurfacing in patients under thirty years old: an attractive option for young and active patients. Int Orthop 36(9):1789–1794

Bernstein M, Desy NM, Petit A, Zukor DJ, Hulk OL, Antoniou J (2012) Long-term follow-up and metal ion trend of patients with metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty. Int Orthop 36(9):1807–1812

Skinner J, Kay P (2011) Commentary: metal on metal hips. BMJ 342:d3009

Sedrakyan A (2012) Metal-on-metal failures—in science, regulation, and policy. Lancet 379(9822):1174–1176

Ng VY, Arnott L, McShane MA (2011) Perspectives in managing an implant recall: revision of 94 durom metasul acetabular components. J Bone Joint Surg Am 93:e100, 1–5

Muirhead-Allwood SK (1998) Lessons of a hip failure. BMJ 316:644

MHRA (2010) Medical Device Alert: Silicone gel filled breast implants manufactured by Poly Implant Prothese (PIP)–All models and lot numbers (MDA/2010/025). Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency, London

Haddad FS, Thakrar RR, Hart AJ, Skinner JA, Nargol AV, Nolan JF, Gill HS, Murray DW, Blom AW, Case CP (2011) Metal-on-metal bearings: the evidence so far. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 93(5):572–579

Berber R, Hothi H, Khoo M, Henckel J, Sabah S, Miles J, Carrington R, Skinner J, Hart A (2014) A new internet enhanced multi-disciplinary team management system for patients with metal on metal hip implants. AAOS 2014 Scientific Exhibit SE07. http://www.aaos.org/education/anmeet/programs/FinalProgram.pdf. Accessed 09 May 2014

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Tibrewal, S., Sabah, S., Henckel, J. et al. The effect of a manufacturer recall on the threshold to revise a metal-on-metal hip. International Orthopaedics (SICOT) 38, 2017–2020 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-014-2369-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-014-2369-z