Abstract

Our aim was to evaluate postoperative morbidity and mortality following initial intervention, comparing primary repair versus palliative shunt in the setting of ductal-dependent tetralogy of Fallot. When neonatal surgical intervention is required, controversy and cross-center variability exists with regard to surgical strategy. The multicenter Pediatric Health Information System database was queried to identify patients with TOF and ductal-dependent physiology, excluding pulmonary atresia. Eight hundred forty-five patients were included—349 (41.3 %) underwent primary complete repair, while 496 (58.7 %) underwent initial palliation. Palliated patients had significantly higher comorbid diagnoses of genetic syndrome and coronary artery anomalies. Primary complete repair patients had significantly increased morbidity across a number of variables compared to shunt palliation, but mortality rate was equal (6 %). Second-stage complete repair was analyzed for 285 of palliated patients, with median inter-stage duration of 231 days (175–322 days). In comparison to primary complete repairs, second-stage repairs had significantly decreased morbidity and mortality. However, cumulative morbidity was higher for the staged patients. Median adjusted billed charges were lower for primary complete repair ($363,554) compared to staged repair ($428,109). For ductal-dependent TOF, there is no difference in postoperative mortality following the initial surgery (6 %) whether management involves primary repair or palliative shunt. Although delaying complete repair by performing a palliative shunt is associated with a shift of much of the morbidity burden to outside of the newborn period, there is greater total postoperative morbidity and resource utilization associated with the staged approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With a prevalence of about 3.9 per 10,000 live births [7], tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) represents 5–7 % of all congenital cardiac lesions [16], making it the most common form of cyanotic congenital heart disease. Degree of right ventricular outflow tract obstruction is variable and exists on a spectrum ranging from mild, unobstructed cases to severe cases with highly significant obstruction. In cyanotic neonates with near complete right to left interventricular shunting at the ventricular septal defect and insufficient prograde flow across the pulmonary valve, prostaglandin (PGE-1) administration is required to maintain ductal patency to ensure adequate pulmonary blood flow until the lesion can be addressed surgically.

There has been longstanding controversy over optimal surgical timing in asymptomatic TOF, but there is general agreement that in such cases of ductal-dependent pulmonary blood flow, a surgical intervention is required in the early neonatal period so that PGE-1 infusion may be discontinued without ensuing cyanosis. Initial choice of surgery for these symptomatic neonates remains controversial [18] with some centers advocating primary neonatal complete repair while other centers instead preferring a staged approach of initial palliation with a systemic to pulmonary artery shunt, with eventual complete repair at a later age.

Despite multiple reports of single center experience suggesting that neonatal repair can be undertaken safely and effectively [11–13], a 2010 analysis of data from the Society of Thoracic Surgeon’s database showed that operations occurring during the newborn period were evenly divided between primary repair and shunt palliation [1]. To our knowledge, however, there are no multi-institutional studies comparing differences in postoperative outcomes for the two surgical strategies. We, therefore, undertook a study to evaluate postoperative morbidity and mortality following initial intervention, comparing primary repair versus palliative shunt in the setting of ductal-dependent TOF.

Methods

The University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Institutional Review Board (IRB) for the Protection of Human Subjects reviewed the study protocol with determination that query of de-identified patient data does not fall under the jurisdiction of the IRB review process.

Data Source

De-identified patient demographic data and data related to postoperative outcomes were abstracted from the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS), an administrative database that contains inpatient data from 43 freestanding, tertiary care children’s hospitals in North America [10]. Institutions in the PHIS database are affiliated with the Child Health Corporation of America (CHCA; Shawnee Mission, KS), a business alliance of children’s hospitals. Hospitals affiliated with the CHCA account for 20 % of all tertiary care children’s hospitals. Institutions are labeled within the database but cannot be identified in public reporting. For the purposes of external benchmarking, participating hospitals provide discharge data including demographic information as well as diagnoses and procedures coded with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes [2]. Billing data are also available detailing medications, imaging studies, laboratory tests, and supplies charged to each patient, and are coded under the Clinical Transaction Classification™ (CTC) System [4]. Data quality and reliability are assured through a joint effort between the CHCA and participating hospitals. The data warehouse function for the PHIS database is managed by Thomson Healthcare (Durham, NC). Individual patient medical record numbers, billing numbers, and zip codes are encrypted. Data are de-identified at the time of submission and are subjected to a number of reliability and validity checks before being processed into data quality reports. Data are accepted into the database once classified errors occur less frequently than a criterion threshold, and the database is updated quarterly by the Child Health Corporation of America. If a hospital’s quarterly data are unacceptable according to these limits, all of their quarterly data are rejected; however, these data can be resubmitted and reevaluated prior to inclusion in the database. PHIS data updates through fourth quarter 2012 are reflected in our data set.

Identification of Study Population

The study group was defined as all patients who were discharged from a PHIS participating hospital between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2011 with a diagnosis code of TOF (ICD-9, 745.2) and evidence of having ductal-dependent pulmonary flow. Determination of ductal-dependent physiology was based on identifying patients with TOF, who were administered PGE-1 (CTC, 191315) within at least 1 day prior to having undergone either surgical complete repair (ICD-9, 35.81) or surgical palliation in the form of a systemic to pulmonary artery shunt (ICD-9, 39.0). Patients were grouped as either primary repair or staged repair based on their initial operation. Those undergoing an initial catheterization procedure to allow for discontinuation of PGE-1 were not included in the study.

Exclusion Criteria

Patients with a coexisting diagnosis of pulmonary valve atresia (ICD-9, 746.01) were excluded from the analysis.

Variables Queried

Patient abstract data queried included age, gender, dates of admission and discharge, total hospital length of stay (LOS), Intensive Care Unit length of stay (ICU-LOS), postoperative days requiring mechanical ventilation, and hospital performing the surgery. Data related to comorbid diagnoses included the presence of a chromosomal abnormality, the presence of a coronary artery anomaly, pulmonary artery atresia, stenosis or hypoplasia, and prematurity. Various interventions associated with post-surgical morbidity were analyzed for their relative frequency of occurrence during each surgical admission. These preoperative comorbidity factors and postoperative interventions, with their corresponding ICD-9 codes, are listed in Table 1.

Pharmacologic data abstracted included names of medications administered, route of administration, and number of postoperative days of administration. Antiarrhythmic medications included amiodarone, flecainide, adenosine, procainamide, propafenone, or sotalol. Oral or intravenous (IV) routes of administration were included for antiarrhythmic drugs. Inotropes/Vasopressors administered included epinephrine, milrinone, norepinephrine, dopamine, or dobutamine. Data for digoxin use were also abstracted but is considered separately from the antiarrhythmics and inotropes since indication for use may vary. Diuretics included furosemide, bumetanide, chlorothiazide, or hydrochlorothiazide. Narcotics included morphine, fentanyl, hydromorphone, or meperidine. Only IV routes of administration were considered for Inotropes/Pressors, diuretics, and narcotics. Hyperalimentation use was also abstracted from the database.

The database was also screened for subsequent admissions of included patients up until December 31, 2012, 1 year beyond the date used for inclusion criteria. For patients who had undergone initial palliation, we then identified the readmission when complete repair was undertaken as a second stage. In this staged repair group, all of the above postoperative data were again analyzed for the second-stage repair admission.

Number of readmissions was tallied for each group, and interventions associated with morbidity were identified during readmissions. Surgical revisions were counted as subsequent episodes of complete repair occurring after an initial repair episode (whether a primary repair or a second-stage repair following palliation). Surgical codes representing individual elements of a complete repair were also abstracted and considered as revisions if they occurred after a complete repair. These potential revision procedures included right ventricular infundibulectomy, ventricular septal defect repair, annuloplasty, and replacement of a pulmonary valve, pulmonary valvotomy, or revision of a surgical procedure on the heart (ICD-9, 35.95). Likewise, subsequent episodes of systemic to pulmonary artery shunt were considered as shunt revisions if occurring following a first episode of palliative shunt. Heart catheterizations were considered separately from surgical revisions.

Total hospital charges associated with the initial operative admission in the newborn period and second-stage complete repair admission following shunt palliation were abstracted from the database. Charges were converted to 2011 dollars by multiplying the 2011 consumer price index (CPI) adjustment factor and dividing by the CPI factor for the year in which the charges were incurred (discharge year). CPI adjustment factors were obtained from the U. S. Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics [3].

Definitions

For the purposes of this study, ductal dependency was defined as cases where PGE-1 was administered and discontinued on the day of, or on the day preceding a surgical repair or palliation. A primary complete repair was defined as the first operative episode occurring without a prior shunt palliation. A palliation was defined as placement of a systemic to pulmonary artery shunt. A second-stage complete repair was defined as complete repair occurring subsequent to an initial palliation. Hospital mortality was defined as death prior to discharge.

Statistical Analysis

All the data were analyzed using statistical software SAS v9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and R v2.15.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Descriptive statistics were summarized as median (25th percentile, 75th percentile) for continuous variables and percentage (n) for categorical variables. Distributions of continuous variables were compared between groups using the Mann–Whitney U tests, and proportions of categorical variables were compared between groups using Chi-square tests. p values less than 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. No adjustment was made for multiple testings or multiple comparisons.

Results

Cohort Description

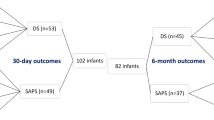

Figure 1 provides a graphic description of the cohort. From January 1, 2004 to December 31, 2011, 7,814 patients from 41 hospitals with the diagnosis of TOF underwent surgical intervention, of which 550 were excluded on the basis of a diagnosis of pulmonary valve atresia. Of the remaining 7,264 patients, 1,123 were administered PGE-1 at some time during their first surgical admission, with 868 of those determined to be ductal dependent. A single patient was excluded secondary to known issues with data integrity from the reporting hospital, leaving 867 patients from 40 hospitals. Of these, 22 underwent both a shunt and a complete repair at the first admission, and thus were excluded from the analysis because postoperative outcome measures could not be considered separately for each operative episode. This yielded a final cohort of 845 patients from 40 hospitals.

Of 845 included patients, 349 (41.3 %) underwent primary complete repair, while 496 (58.7 %) underwent initial palliation with systemic to pulmonary artery shunt. Patients undergoing initial palliation had significantly higher comorbid diagnoses of genetic syndrome (22 vs. 12 %, p < 0.001) and coronary artery anomalies (6 vs. 3 %, p = 0.024) in comparison to those undergoing primary complete repair. No difference in the prevalence of prematurity or pulmonary artery atresia, stenosis or hypoplasia was found between the two groups. Two hundred eighty-five of the initially palliated patients were identified as having undergone a complete repair as a second stage, with a median inter-stage duration of 231 days (interquartile range of 175–322 days).

Post-surgical In-hospital Mortality

Table 1 shows a comparison of demographic data and postoperative data following the first surgery between those who underwent primary repair and those who underwent palliation. There was no significant difference in postoperative in-hospital mortality between the two groups, with both groups having 6 % mortality—32 of 496 shunted patients not surviving until discharge and 20 of 349 primary complete repair patients not surviving to discharge.

Table 2 shows a comparison of postoperative data between primary complete repairs performed in the newborn period and complete repair performed as a second-stage following palliation. Of patients who underwent a complete repair as a second-stage following palliation, there was 1 % (3 of 285) in-hospital mortality following the repair procedure. Two hundred eleven of the 496 patients undergoing a shunt as an initial procedure were lost to follow-up prior to undergoing complete repair.

Post-surgical In-hospital Morbidity

As shown in Table 1, when considering only the first surgical admission, those who underwent a primary complete repair had significantly greater median postoperative intensive care unit length of stay (11 vs. 8 days, p < 0.001), duration of mechanical ventilation (7 vs. 5 days, p = 0.022), requirement for antiarrhythmic drugs (24 vs. 9 %, p < 0.001), requirement for chest tube insertion (12 vs. 7 %, p = 0.014), and duration of administration of inotropes/vasopressors (5 vs. 4 days, p < 0.001) and IV diuretics (9 vs. 6 days, p < 0.001), in comparison to those who underwent shunt palliation.

As shown on Table 2, in comparison to complete repair that occurred following initial palliation, primary neonatal complete repair was associated with significantly higher postoperative death prior to discharge (6 vs. 1 %, p = 0.002), total hospital length of stay (23 vs. 10 days, p < 0.001), intensive care unit length of stay (11 vs. 6 days, p < 0.001), duration of mechanical ventilation (7 vs. 2 days, p < 0.001), and duration of requirement for inotropes/vasopressors (5 vs. 3 days, p < 0.001), IV diuretics (9 vs. 6 days, p < 0.001), IV narcotics (7 vs. 5 days, p < 0.001), and hyperalimentation (9 vs. 4 days, p < 0.001).

Table 3 shows a comparison of postoperative data between patients undergoing primary repair and staged repair, combining data from both surgical admissions for the staged group. When considering a summation of both operative episodes, patients who underwent a two-stage repair had greater combined median postoperative total hospital LOS (35 vs. 23 days, p < 0.001), ICU-LOS (14 vs. 11 days, p < 0.001), duration of mechanical ventilation (8 vs. 7 days, p = 0.002), and requirement for all queried medications in comparison to those who underwent a single-stage repair.

Hospital Charges

Median adjusted billed charges reflect a significant cost savings associated with primary complete repair in comparison to a two-stage approach ($363,554 for primary complete repair versus $428,109 for shunt palliation and second-stage repair combined, p < 0.001). Only the first surgical admission and second-stage repair admission were considered to determine resource utilization. Figures have been inflation adjusted to 2011 dollars [3].

Readmissions and Surgical Revisions

Table 4 summarizes readmission data and interventions required at readmission. The staged repair group consists of 285 initially palliated patients who were successfully followed forward to a second-staged repair. Rates of readmission were similar between the primary repair and staged repair groups. Of the primary repaired group, 50 % required readmission with 11 % requiring a subsequent complete repair revision or other intra-cardiac surgical revision. Of the staged repair patients who could be followed to eventual complete repair, 45 % required readmission in the inter-stage period between shunt and complete repair, with 6 % requiring shunt revision. There was a 44 % readmission rate following complete repair performed as a second stage, with 7 % requiring intra-cardiac revision following the completed second-stage repair. No significant difference with regard to prevalence of morbidity-associated procedures performed at readmission was found.

Center Variability

Significant cross-center variability with regard to surgical strategy was found. Figure 2 is a bar plot displaying each center (x-axis) bars arranged from left to right according to percentage of complete repairs performed (left side y-axis). Dots are overlaid corresponding to center volume (right side y-axis). No relationship between center volume and preferred strategy was found. At the extremes are three centers that performed primary complete repairs on 100 % of patients, and four centers that exclusively performed shunt palliations (0 % primary complete repairs). For centers that performed primary complete repairs on greater than half of their caseload, there was an association of shunt palliation with the presence of comorbid coronary artery anomalies, prematurity, genetic syndromes, or pulmonary artery atresia/stenosis/hypoplasia.

Approach varies across centers. Percentage of primary complete repairs for each hospital (vertical bars correspond to the left side of the y-axis). Each hospital’s total volume of ductal-dependent tetralogy of Fallot patients addressed surgically is also shown (diamonds correspond to the right side of the y-axis)

Sub-analysis of “Standard Risk” Patients

A sub-analysis was performed after exclusion of patients carrying comorbid diagnoses of prematurity, genetic syndrome, coronary artery anomaly, or pulmonary artery atresia/stenosis/hypoplasia. One hundred eight patients were excluded from the primary complete repair group (n = 241), while 205 were excluded from the palliative shunt group (n = 291). Postoperative in-hospital mortality following the first index surgery was found to be higher in those having undergone shunt palliation in comparison to those having undergone primary complete repair (8 vs. 4 %, p = 0.044). A comparison of postoperative data for these standard risk subgroups following the first index surgery is provided in Table 5.

Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to provide guidance in selecting an optimal operative strategy for ductal-dependent TOF in the neonatal period. With advancement in intra-operative technology and postoperative ICU care, there is an increasing trend toward primary complete surgical repair rather than shunt palliation [19], and some centers have moved toward reserving initial palliation only for extreme cases with limiting anatomic features such as anomalous coronary arteries or pulmonary artery discontinuity [14]. Forgoing the classical step of initial shunt palliation and performing early primary neonatal repair has also become an accepted strategy for cyanotic infants with pulmonary atresia or severe right ventricular outflow tract obstruction [9, 13]. Reports documenting morbidity related to right pulmonary artery distortion, pulmonary vaso-occlusive disease, and even mortality relating to thrombosis in the setting of neonatal shunts in a biventricular circulation have provided some justification for this shift in strategy [5, 6]. At the same time, other reports have shown equivalent early survival rates with no inter-stage mortality following shunt palliation [8].

The mortality rate observed in this study is consistent with findings from our previous study, which found that elective repair in the neonatal period was associated with a significantly higher mortality than in older patients (6.4 vs. 1.3 %) [15]. Moreover, the present study of non-elective neonatal cases found that this mortality rate holds, even for those patients who were palliated with a shunt. Importantly, there was no difference found for initial postoperative mortality regardless of the choice of first operation—either primary complete repair or shunt palliation. This contradicts the idea that shunt palliation is a “safer approach” in the neonatal population, and therefore warrants closer inspection.

Our data suggest that significantly higher proportions of patients were selected for shunt palliation because of their associated comorbidities of genetic syndromes or coronary artery anomalies. It could, therefore, be argued that a staged repair strategy was reserved for a higher risk group with an inherently increased risk of mortality and morbidity, leading to artificially inflated mortality following shunt palliation. However, contrary to expectation, in re-analyzing the data after excluding patients with associated comorbid diagnoses, we found that the staged approach was actually associated with a higher postoperative in-hospital mortality following initial intervention in comparison to primary complete repair (8 vs. 4 %). This surprising finding suggests that this ductal-dependent neonatal population is inherently at higher risk for in-hospital mortality, and that this risk is not significantly mitigated by choosing shunt palliation over complete neonatal repair.

There were significant differences in postoperative morbidity, as primary complete repair was associated with a significantly higher morbidity burden in the newborn period in comparison to shunt palliation. This was evidenced by increased ICU-LOS, duration of mechanical ventilation, requirement for chest tube insertion, and IV medication requirement. Similarly, the comparison of primary complete repair to complete second-stage repair following palliation showed that delaying the definitive procedure to beyond the neonatal period was associated with decreased total hospital LOS and ICU-LOS, duration of ventilator requirement, and medication requirement following the repair surgery. Importantly, however, this advantage in morbidity does not hold true when data from the two admissions in the staged approach are combined. On the contrary, the present study shows an association of significantly less overall cumulative postoperative morbidity associated with the single operation in the primary complete repair group.

Our analysis of the monetary impact of the difference in approach provided similar information. Specifically, while each individual admission in a staged repair incurred fewer charges than a primary repair, there was significant overall cost savings in comparison to the staged approach when the cumulative cost is considered. Furthermore, one might expect that the greater total requirement for readmissions in the staged repair group might be associated with an even greater increase in the overall financial cost relative to the primary repair group, but cost of all readmissions was not analyzed. The monetary savings associated with a single-stage repair versus a staged approach have been previously reported in single center experience [17], and our data mirror this on a large multicenter scale; a finding that is particularly relevant in the current climate of healthcare reform.

Physiologic rationale underlying early primary repair strategies include prevention of cyanotic end organ damage, removing the stimulus for right ventricular hypertrophy and fibrosis, promoting pulmonary artery growth, and improved vascular and alveolar lung development [5, 8, 9]. Also, the need for only one operation has theoretical advantages of easing anxiety associated with anticipation of the second stage as well as potentially less interruption to the lives of family members. The findings from this study could be interpreted to signify that an approach of primary complete repair in the neonatal period is, in fact, a superior strategy, with no increase in mortality and an overall decrease in postoperative morbidity compared to a two-stage approach. Our data do also show that a staged repair strategy is associated with a shift of much of the morbidity burden to outside of the neonatal period, but whether this is beneficial to the patients in the long term is beyond the scope of this study.

At present, there is no consensus with regard to management strategy as evidenced by near equal prevalence of palliation versus primary repair in patients less than 30 days old in a recent analysis of the STS database [1]. Our data confirm this extreme variability in repair strategy with primary repair undertaken 41 % of the time and a staged approach with initial palliation occurring 59 % of the time across 40 centers. The analysis by center would suggest that center preference is a key driver of approach to repair strategy, with some centers exclusively performing palliations and others exclusively undertaking primary repair. A number of centers with primary complete repair representing greater than 50 % of their caseload have reserved shunt placement only for higher risk patients. This was evidenced by the fact that, for these centers, the number of palliations performed corresponded to number of patients with comorbid diagnoses of coronary anomalies, pulmonary arteriopathy, prematurity, or genetic syndromes. In spite of significantly increased prevalence of coronary artery anomalies and genetic syndromes found in the shunt palliated patients, the absolute number of patients diagnosed with these comorbidities is not sufficient to explain the variation, and it is clear that there is varying approach to strategy across centers.

Study Limitations

Significant inter-stage attrition was experienced. This may have resulted from inability to follow a patient across centers, second-stage repair occurring beyond the date range, an alternate diagnosis being given at a subsequent admission, or out of hospital mortality. In spite of many reports of low inter-stage mortality, it is unknown what proportion of attrition is due to inter-stage mortality in the palliated group. The extent of bias affecting the readmission and second-stage postoperative data in the palliated group secondary to inter-stage attrition is unknown. Also, 22 patients underwent both shunt and complete repairs on the same admission and were thus excluded from the analysis because postoperative outcome measures could not be considered separately for each operative episode. Circumstances of the clinical course for these patients are unknown, and their exclusion is a potential source of bias within the data. In consideration of postoperative morbidity-associated interventions, the fidelity of the data did not allow for determination if a catheter-based intervention occurred during a catheterization procedure. Furthermore, the possibility of a catheter-based intervention as the primary intervention allowing for discontinuation of PGE-1 was not addressed by the study design, as any such patients would not have met inclusion criteria. In consideration of resource utilization, hospital charges were determined only from the first surgical admission and second-stage repair admission. Although a number of readmissions and interventions required at readmission were determined for each group, the cost of readmissions was not analyzed.

Finally, the study is subjected to the limitations of any observational investigation, including selection bias and the potential impact of confounders. A randomized, prospective study is required to provide conclusive evidence regarding equivalence or potential superiority of one strategy over the other, but it would likely be limited its relatively small sample size. In spite of the limitations inherent in an administrative database such as PHIS, we believe that there is strong ability to address immediate postoperative outcome measures associated with alternative repair strategies in a large sample of patients drawn across multiple institutions.

Conclusions

There is significant variability in repair strategy across the cohort, and the decision to pursue initial palliation rather than repair in the setting of ductal-dependent TOF which is only partially driven by the presence of comorbidities such as coronary artery anomalies or genetic syndromes. There is no difference in postoperative mortality following the initial surgery (6 %) whether management involves primary repair or palliative shunt. Although delaying complete repair by performing a palliative shunt is associated with a shift of much of the morbidity burden to outside of the newborn period, there is greater total postoperative morbidity and resource utilization associated with the staged approach. This retrospective analysis is suggestive that complete neonatal repair may be considered an equivalent, if not somewhat superior strategy for patients with ductal-dependent TOF, but a randomized prospective study is required to conclude this definitively.

Abbreviations

- TOF:

-

Tetralogy of Fallot

- PGE-1:

-

Prostaglandin-E1

- PHIS:

-

Pediatric Health Information System

- ICD-9:

-

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision

- CTC:

-

Clinical Transaction Classification™ system

- LOS:

-

Length of stay

- ICU-LOS:

-

Intensive Care Unit length of stay

- CPI:

-

Consumer price index

References

Al Habib HF, Jacobs JP, Mavroudis C, Tchervenkov CI, O’Brien SM, Mohammadi S et al (2010) Contemporary patterns of management of tetralogy of Fallot: data from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Database. Ann Thorac Surg 90:813–819; discussion 819-820

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics (2013) International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd9cm.htm. Accessed 3 May 2013

Consumer Price Index, All Urban Consumers (2013) U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. http://www.bls.gov/cpi/. Accessed 27 Aug 2013

CTC Resources (2013) Child Health Corporation of America. http://www.chca.com/index_flash.html. Accessed 3 May 2013

Fermanis GG, Ekangaki AK, Salmon AP, Keeton BR, Shore DF, Lamb RK et al (1992) Twelve year experience with the modified Blalock–Taussig shunt in neonates. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 6:586–589

Gladman G, McCrindle BW, Williams WG, Freedom RM, Benson LN (1997) The modified Blalock-Taussig shunt: clinical impact and morbidity in Fallot’s tetralogy in the current era. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 114:25–30

Improved National Prevalence Estimates for (2006) 18 Selected Major Birth Defects—United States 1999–2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 54:1301–1305

Kanter KR, Kogon BE, Kirshbom PM, Carlock PR (2010) Symptomatic neonatal tetralogy of Fallot: repair or shunt? Ann Thorac Surg 89(3):858–863

Mulder TJ, Pyles LA, Stolfi A, Pickoff AS, Moller JH (2002) A Multicenter analysis of the choice of initial surgical procedure in tetralogy of Fallot. Pediatr Cardiol 23:580–586

Owner Hospitals (2013) Child Health Corporation of America. http://www.chca.com/index_flash.html. Accessed 3 May 2013

Park CS, Kim WH, Kim GB, Bae EJ, Kim JT, Lee JR, Kim YJ (2010) Symptomatic young infants with tetralogy of Fallot: one-stage vs staged repair. J Card Surg 25:394–399

Parry AJ, McElhinney DB, Kung GC, Reddy VM, Brook MM, Hanley FL (2000) Elective primary repair of acyanotic tetralogy of Fallot in early infancy: overall outcome and impact on the pulmonary valve. J Am Coll Cardiol 36:2279–2283

Pigula FA, Khalil PN, Mayer JE, del Nido PJ, Jonas RA (1999) Repair of tetralogy of Fallot in neonates and young infants. Circulation 100(19 Suppl):157–161

Sousa Uva M, Chardigny MC, Galetti L, Lacour Gayet F, Roussin R, Serraf A et al (1995) Surgery for tetralogy of Fallot at less than six months of age. Is palliation “old-fashioned”? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 9:453–459; discussion 459–460

Steiner MB, Tang X, Gossett JM, Malik S, Prodhan P (2014) Timing of complete repair of non-ductal-dependent tetralogy of Fallot and short-term postoperative outcomes, a multicenter analysis. J Thoracic Cardiovasc Surg 147:1299–1305

Talner CN (1980) Report of the New England Regional Infant Cardiac Program. Pediatrics 65(suppl):375–461

Ungerleider RM, Kanter RJ, O’Laughlin M, Bengur AR, Andreson PA, Herlong JR et al (1997) Effect of repair strategy on hospital cost for infants with tetralogy of Fallot. Ann Surg 225:779–783; discussion 783–784

Van Arsdell GS, Maharaj GS, Tom J, Rao VK, Coles JG, Freedom RM et al (2000) What is the optimal age for repair of tetralogy of Fallot? Circulation 102(19 Suppl 3):III123–129

Vobecky SJ, Williams WG, Trusler GA, Coles JG, Rebeyka IM, Smallhorn J et al (1993) Survival analysis of infants under 18 months presenting with tetralogy of Fallot. Ann Thorac Surg 56:944–950

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Steiner, M.B., Tang, X., Gossett, J.M. et al. Alternative Repair Strategies for Ductal-Dependent Tetralogy of Fallot and Short-Term Postoperative Outcomes, A Multicenter Analysis. Pediatr Cardiol 36, 177–189 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00246-014-0983-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00246-014-0983-6