Abstract

Purpose

There is little research-based documentation on the services provided by drug information centres (DICs). The aim of this multi-centre study was to explore for the first time the factors associated with time consumption when answering drug-related queries at eight different but comparable DICs.

Methods

During an 8-week period, staff members at eight Scandinavian DICs recorded the number of minutes during which they responded to queries. Mixed model linear regression analyses were used to explore the factors associated with time consumption when answering queries.

Results

The mean time consumption per query was 178 min (range 4–2540 min). The mean time consumed per query increased by 28 (95 % confidence interval (CI) 23 to 33, p < 0.001) min higher for queries for which there was a lack of documentation and 139 (95 % CI 74 to 203, p < 0.001) min higher when conflicting information was present in the literature. Staff members with less than 1 year of experience consumed a mean of 91 more minutes (95 % CI 32 to 150, p = 0.003) per query than staff members with more than 2 years of experience.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates the large variation in time consumed answering queries posed to Scandinavian DICs. The results highlight the need for highly competent staff members and easy access to drug information sources. Further studies are required to explore the association between time consumption and response quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, drug information centres (DICs) vary with regard to affiliation (pharmacies, universities, university hospitals), staff competence (pharmacists and/or physicians) and working methods (i.e. providing solely factual drug information or providing clinical decision support) [1–6]. Within Scandinavia, DICs are relatively similar: they are regional DICs staffed by pharmacists and clinical pharmacologists who cooperate to answer queries from healthcare professionals [2–4]. The Scandinavian DICs share important features [2–4, 7–14]. They are, to varying degrees, affiliated with clinical pharmacology departments at university hospitals. The centres are funded by the public healthcare system in their respective countries, and their information is independent of commercial interests. Queries to Scandinavian DICs are typically patient related and concern adverse effects, drug interactions, drug use during pregnancy or breast-feeding and drug choice recommendations. The majority of queries are posed by physicians, and decision support is frequently requested [2–4]. DICs provide a valuable service by evaluating and compiling literature sources related to specific clinical situations [4]. The working process of these centres has been described previously [2–4].

The processes involved in providing an answer to a drug-related query are time consuming. The majority of scientific literature is available on the Internet, but knowing where and how to search, how to interpret and critically evaluate literature and how to extract essential information related to a particular clinical case require considerable knowledge and practical training. There are few research-based data on the factors associated with time consumed answering queries submitted to DICs. Lyrvall et al. studied time consumed answering queries at one Swedish DIC. Of the 100 randomly selected queries from 1989, the time was registered for 98 queries. The mean time consumption was 187 min, whereas the median was 128 min (range 19–1240 min) [15]. Based on data from a pharmacist-manned DIC in the USA, Timpe et al. reported that complex queries, i.e. those that require evaluation of primary literature and critical thinking skills, were answered within a longer time frame (mean 2.37 h) than simple queries, i.e. queries for which no such evaluation or critical thinking skills are necessary (mean 0.38 h) [16].

In a preliminary study of Norwegian DICs [14], we aimed to develop a model describing the factors associated with time consumed answering queries. The type of literature search performed (none, simple - search in monographs, databases, summary of product characteristics (SPCs) etc., advanced - search in databases such as Medline to identify original articles)and queries considered judgmental (queries that require the integration of data or knowledge and experience in the process of making a decision regarding a specific problem [17]) were significantly associated with time consumption, whereas the number of drugs involved had no effect [14]. The model we developed did not describe all factors that may affect time consumed addressing queries, as there are likely numerous additional factors that affect time related to the query itself and the manner in which it is handled. In addition, our previous study was small and limited to Norwegian DICs.

The present study was conducted to describe time consumption when answering drug-related queries to Scandinavian DICs and to identify factors affecting this variable.

Material and methods

Settings and study population

In the autumn of 2012, we contacted 11 Scandinavian DICs and presented the protocol for this study. Eight centres (four Norwegian, three Danish and one Swedish centre) chose to participate. The primary reason for not participating was lack of resources. Each of the 66 staff members answering queries during the study was provided a unique identifier that was employed throughout the study period. The registration of the personal data provided by individual staff members was reported to the Norwegian Social Science Data Services in accordance with national legislation.

Data collection

The study took place during the 8-week period between January 14 and March 10, 2013. Of the 769 incoming queries during this period, 718 (93 %) were included in the study. For the remaining 51 queries, data were not reported for 37, and 14 were excluded because they were not posed by healthcare professionals. The study period length was chosen based on the normal query volume at the centres during such a time period. The registered variables are shown in the Electronic supplementary material, Table 1. During the study, staff members registered the number of minutes consumed on each query, specified in five sub-categories of tasks. Time spent by colleagues involved in preparing the response was also included.

Statistical analysis

We used a linear mixed model with the total number of minutes registered as the dependent variable, staff members and centres as random effects and the following as covariates: the number of drugs involved, the number of sources consulted, the staff member’s experience, gender and profession, lack of documentation, presence of conflicting documentation, a particularly complex patient case, heavy workload at the time and agreed response time. The analyses were performed with one covariate at a time. The dependent variable time was not normally distributed; therefore, we also performed analyses using log-transformed time as the dependent variable. These analyses yielded essentially the same results. We report the results of the analysis of the untransformed data which are more easily interpretable. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (CI) are provided when relevant, and two-sided p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Regarding the agreed response time, the categories unknown, others and response time not agreed (n = 191) were excluded from the analyses. Data were analysed using SPSS 21.

Results

Of the 718 included queries, physicians posed 512 (71.3 %) and pharmacists 120 (16.7 %), whereas others (e.g. nurses, dentists and healthcare students) posed the remaining 86 (12.0 %). A total of 558 queries (77.7 %) concerned one or more specific patients. The mean number of drugs involved in the queries was 2.4 (median 1, range 1–19). The mean number of information sources consulted per query was 4.6 (median 4, range 0–14). No search was performed in 17 cases (2.4 %), a simple search was performed in 327 cases (45.5 %) and an advanced search was performed in 373 cases (51.9 %) (one case missing). One or more recommendations were provided in 636 cases (88.6 %). In 361 cases (56.8 %), recommendations specific to the case were provided, and in the remaining 275 cases (43.2 %), only general recommendations were provided.

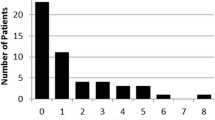

The time consumed when answering the 718 queries varied from 4 to 2540 min, with a mean of 178 min. The distribution of time consumption is shown in Fig. 1. Figure 2 depicts the mean time consumed in each of the five categories of tasks at each of the eight centres. The mean time consumed per query increased by 28 min for each literature source consulted. Table 1 shows the results of the linear regression analysis of the association of the variables with the time consumed answering queries. The mean time consumption was 60 min higher for queries for which there was a lack of documentation and 139 min higher when conflicting information was present in the literature. Staff members with less than 1 year of experience consumed a mean of 91 more minutes per query than staff members with more than 2 years of experience (Table 1).

The time consumption as a function of the query category and the number of queries answered by staff members stratified by their experience, gender and academic qualifications are shown in the Electronic supplementary material, Table 2 and Table 3, respectively.

Discussion

This study showed that there is considerable variability in the time consumed processing drug-related queries to Scandinavian DICs. Our results are similar to results for other European [14, 15, 18, 19] and American [16, 20] DICs. The variability in time consumption and the skewed distribution of data (Fig. 1) are not surprising: most queries are handled efficiently within a few hours, but for a small number of queries, the time consumed represents more than a full working day. These queries typically concern particularly complex patient cases and drug treatment regimens. In addition, scientific documentation may be lacking, inconclusive or conflicting in the various information sources available. Table 1 illustrates that the complexity of queries, measured in terms of lack of documentation, conflicting documentation and particularly complex patient cases, is significantly associated with time consumption.

In the present study, the number of minutes consumed processing a response is comparable to results from Lyrvall et al., who reported data from a Swedish DIC in 1989 [15]. Although the basic procedure for handling a drug-related query remains the same, many changes have occurred in 25 years that may affect time consumption. In 1989, the Internet was not used for searches, and copies of scientific articles often had to be ordered from the library. Although databases such as MEDLINE were available in 1989 [15], the accessibility of the scientific literature is easier today. On the other hand, the magnitude of available literature on a specific subject is often considerably greater now. Furthermore, an increase in polypharmacy and more complex drug treatment regimens [21] may explain the lack of reduction in time consumption despite improvements in search capability.

In the present study, the total time consumption was considerably different between centres, which might reflect the centres’ and/or staff members’ working routines. There are some well-known differences between centres with this respect, e.g. how strict their search strategies are and the mean number of literature sources consulted. In addition, some centres produce an English answer for a database in addition to an answer in the native language of the enquirer, which may require additional writing time. The differences in total time consumption between centres might also be due to differences in the characteristics of the queries posed to the various centres, although we have no evidence that such differences in characteristics were present.

The demographic characteristics of the staff members handling the queries were of minor importance to time consumption, with the exception of work experience. Unsurprisingly, more experienced staff members handled queries more swiftly than staff members with relatively little experience. However, within the group of subjects with working experience >2 years, there was no association between experience and time consumption (data not shown). Approximately half of the queries in the present study were answered by staff members with less than 2 years of experience (see the Electronic supplementary material, Table 3). We have previously estimated that 3–6 months of training are necessary to learn the basics of addressing a query [14]. The observation that a relatively long period of training is required, even for pharmacists and doctors, to handle a query efficiently, reflects the complexity of the work involved in producing responses to these queries.

The agreed response time significantly affected the time consumed answering queries: the longer the agreed response time was, the longer was the effective time consumed answering a query (Table 1). The agreed response time might reflect the time frame within which the enquirer requires an answer, but might also be the result of dialogue between the enquirer and staff member estimating how much time is required to answer the query, e.g. based on knowledge about its complexity. In addition, a response provided on the same day the query was asked obviously cannot exceed an effective working time of 7–8 h, thereby naturally limiting time consumption when a rapid response is required.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first international multi-centre study exploring factors associated with time consumed answering queries to DICs. The participating centres are similarly organised, receive the same types of queries and use the same overall working methods [2–4, 12–15]. We sampled a large consecutive cohort of queries that are reasonably representative of the everyday working process. Although the results are primarily valid for DICs in Scandinavian countries, they may also be relevant to DICs with similar organisations and type of queries from healthcare professionals in other countries. In addition, the results should be of interest to the healthcare funding authorities. The time consumed answering these queries emphasises that researching the answers to these queries cannot be left to enquiring healthcare professionals, whose time is engaged in clinical practice. The answer process requires high competence and experience in all aspects of pharmacology among staff members, as well as training in information search strategies and compilation of written and verbal answers. Factors of importance for swift processing and high quality of a response include easy access to drug literature and systems for ensuring efficiency, e.g. documentation of previous responses, cooperation between centres and quality assurance systems.

Factors that were unaccounted for in this study may affect the time consumed working with queries. For example, this study did not measure patient-specific factors complicating the queries and the personal interests and knowledge of staff members on specific topics. The work situation may also be affected by other working tasks, disruptions and stress. Staff members were asked to express to what degree they felt they had a heavy workload at the time of the query, but workload did not significantly affect time consumption (Table 1).

We observed no differences between men and women, pharmacists and physicians or staff members with and without a PhD, but we observed differences in the length of DIC work experience. Although these results appear plausible, queries were not randomly assigned to staff members, and we cannot ensure that a non-random query distribution did not bias the results. For example, more complex queries may be assigned to staff members with a PhD. In addition, due to the open nature of the study, all staff members were aware of their participation, which might have affected the outcome parameters.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates a large variation in the time consumed responding to drug-related queries to Scandinavian DICs and highlights the nature and complexity of the DIC services. The number of sources searched and the availability and conformity of the literature appear to be principal determinants of time consumption. These findings indicate the need for highly competent staff members and easy access to drug information sources at DICs. However, whether time consumption affects answer quality remains unknown.

References

Smith JM (1987) Drug information in Europe. The state of the art and future prospect. J Pharm Clin 6:71–80

Schjøtt J, Pomp E, Gedde-Dahl A (2002) Quality and impact of problem-oriented drug information: a method to change clinical practice among physicians? Eur J Clin Pharmacol 57:897–902

Hedegaard U, Damkier P (2009) Problem-oriented drug information: physicians’ expectations and impact on clinical practice. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 65:515–22

Alván G, Andersson ML, Asplund AB et al (2013) The continuing challenge of providing drug information services to diminish the knowledge–practice gap in medical practice. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 69:S65–S72

Rosenberg JM, Schilit S, Nathan JP et al (2009) Update on the status of 89 drug information centers in the United States. Am J Health-Syst Pharm 66:1718–21

Lim L-Y, Chui W-K (1999) Pharmacist-operated drug information centres in Singapore. J Clin Pharm Therapeut 24:33–4

Alván G, Öhman B, Sjöqvist F (1983) Problem-oriented drug information: a clinical pharmacological service. Lancet 322:1410–2

Öhman B, Alván G, Nilsson I et al (1989) DIC network—the Swedish model. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 36:A252

Öhman B, Lyrvall H, Alván G (1993) Use of Drugline—a question-and-answer database. Ann Pharmacother 27:278–84

Lyrvall H, Nordin C, Jonsson E et al (1993) Potential savings of consulting a drug information center. Ann Pharmacother 27:1540

Llerena A, Öhman B, Alván G (1995) References used in a drug information centre. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 49:87–9

Öhman B, Lyrval H, Törnqvist E et al (1992) Clinical pharmacology and the provision of drug information. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 42:563–8

Schjøtt J, Reppe LA, Roland P-DH et al (2012) A question-answer pair (QAP) database integrated with websites to answer complex questions submitted to the regional medicines information and pharmacovigilance centres in Norway (RELIS): a descriptive study. BMJ Open 2:e000642. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000642

Reppe LA, Spigset O, Schjøtt J (2010) Which factors predict the time spent answering queries to a drug information centre? Pharm World Sci 32:799–804

Lyrvall H, Öhman B, Alvàn G. [Prosjektrapport om tidsstudie utförd jan 1989—maj 1990 vid Läkemedelsinformationscentralen och Institutionen för klinisk farmakologi, Huddinge Sjukhus]. In: Lyrvall H (1994). [Problemorienterad läkemedelsinformation—en möjlighet att förbättra sjukvårdens kvalitet] [Dissertation in Swedish]. Dissertation, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm

Timpe EM, Motl SE (2005) Frequency and complexity of queries to an academic drug information center 1995–2004. Am J Health-Syst Pharm 62:2511–4

Grace M, Wertheimer AI (1975) Judgmental questions processed by a drug information center. Am J Hosp Pharm 32(9):903–4

Schwarz UI, Krappweis J, Stoelben S et al (1998) Drug information services: initial experience in Dresden. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 54:667–8

Müllerova H, Vlcek J (1997) Drug information centre—analysis of activities of a regional centre. Int J Med Info 45:53–8

Joy ME, Arana CJ, Gallo GR (1986) Use of information sources at a university hospital drug information service. Am J Hosp Pharm 43:1226–9

Hovstadius B, Hovstadius K, Åstrand B et al (2010) Increasing polypharmacy—an individual-based study of the Swedish population 2005–2008. BMC Clin Pharmacol. doi:10.1186/1472-6904-10-16

Acknowledgments

We thank the leaders and staff members of all the participating DICs for contributing to this study. The study was funded by a grant from the Faculty of Health Sciences, Nord-Trøndelag University College, and a grant from the four Norwegian Regional Medicines Information and Pharmacovigilance centres.

Ethical standards

The manuscript does not contain clinical studies or patient data.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributions of authors’ statement

Linda Reppe, Olav Spigset and Jan Schjøtt got the idea of the study and designed the study in cooperation with Ylva Böttiger, Hanne Rolighed Christensen, Jens Peter Kampmann and Per Damkier. Linda Reppe organised the practical arrangements of the study and collected data. Linda Reppe and Stian Lydersen have performed the statistical analysis. All authors have contributed to the interpretation of findings and writing of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 21 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Reppe, L.A., Spigset, O., Böttiger, Y. et al. Factors associated with time consumption when answering drug-related queries to Scandinavian drug information centres: a multi-centre study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 70, 1395–1401 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-014-1749-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-014-1749-z