Abstract

Low-trauma fractures of elderly persons are a major public health problem. However, epidemiologic knowledge on their fresh secular trends is scarce. Trends in the number and incidence (per 100,000 persons) of low-trauma fractures of the pelvic ring among older Finns were assessed by taking into account individuals 80-year-old or older who were admitted to Finnish hospitals for primary treatment of such injury in 1970–2013. The number and age-adjusted incidence of these fractures increased considerably between 1970 and 2013, from 33 (number) and 73 (incidence) in 1970 to 1055 and 364 in 2013. The age-specific incidence of fracture also increased in all age groups (80–84, 85–89, and 90–) of women and men during the entire study period. If the fracture incidence continues to rise at the same rates as in 1970–2013 and the size of the 80-year-old or older population of Finland increases as predicted (87 % by the year 2030), the number low-trauma pelvic fractures in this population will be 2.4 times higher in the year 2030 (2550 fractures) than it was in 2013 (1055 fractures). The number of low-trauma fractures of the pelvis among Finns 80 years of age or older has risen sharply between 1970 and 2013—with a rate that cannot be explained merely by demographic changes. Further studies are urgently needed to better assess the reasons for the rise and possibilities for fracture prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Low-trauma fractures (also called fall-induced fractures or osteoporotic fragility fractures) of elderly persons are a major public health concern in modern societies [1–3]. However, updated epidemiologic information on the long-term secular trends of older adults’ fractures is limited, and this also concerns fractures of the pelvic ring [1–5]. The pelvic fractures are not as frequent as those at the spine, proximal femur, proximal humerus, and distal forearm, but yet they are serious injuries that often require a long period for healing with accompanying impairment, disability, long-term treatment and rehabilitation, and high costs. Additionally, older adults’ pelvic fractures possess an increased risk for considerable morbidity and mortality [6–8].

Our previous study indicated that the number and incidence of Finnish women 80 years of age or older who were admitted to hospitals because of a low-trauma pelvic fracture clearly rose between 1970 and 2002 [9]. We have now continued the follow-up of this high-risk group of women 11 years more (till the end of 2013) to assess most recent changes. In addition, now the database of pelvic ring fractures also includes 80-year-old or older Finnish men.

Methods

The data of the low-trauma fractures of the pelvic ring (fractures of the proximal femur were excluded) originated from the Finnish National Hospital Discharge Register (NHDR). This statutory, computer-based register is the oldest nationwide discharge register in the world and has been in operation since 1967.

The Finnish NHDR provides reportedly reliable data for severe injuries and their causes in Finland, a country with a well-defined Caucasian white population of 5.4 million people [10–13]. In calculating the incidence rates of fracture, annual midyear populations were taken from the Official Statistics of Finland, the statutory, computer-based population register of the country [14].

Throughout the study years, a low-trauma pelvic fracture was defined as a fracture occurring in persons 80 years of age or older as a consequence of moderate or minimal trauma only (that is, a fall from a standing height of 1 m or less). Fractures caused by vehicular accidents and other types of high-energy trauma were excluded. The personal identification number system of the Finns allowed us to focus the analysis on each patient’s first recorded admission only.

The pelvic fracture diagnoses were labelled with a five-digit code according to the eighth, ninth, and tenth revisions of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-8, ICD-9, ICD-10) that indicated the type of fracture. Between 1970 and 1986, the eighth revision of the ICD and its codes for pelvic fractures (80,800 and 80,810) were used. Between 1987 and 1995, the corresponding ICD-9 code classes were 8080A–8085A, 8088X, and 8089X, and, between 1996 and 2013, the corresponding ICD-10 code classes were S32.1–S32.5, S32.7, and S32.8. In the Finnish NHDR, the cause of injury (level of trauma) is given via E-codes. In the current study, the fall-induced low-trauma E-codes were E8809–E8879 in 1970–1986; E880A, E881A, E883A, and E889A in 1987–1995; and W00, W01, W06, W09, W10, W11, and W19 in 1996–2013.

In calculating the annual age-adjusted incidence of fracture (per 100,000 individuals 80 years of age or older), the age adjustment was done by means of direct standardization using the mean 80-year-old or older female and male population between 1970 and 2013 as the standard population. The age-specific fracture rates (per 100,000 individuals) were examined in three 5-year age groups (80–84, 85–89, and 90–).

The pelvic fracture data were drawn from the entire 80-year-old or older population of Finland, which was 50 943 in 1970 and 270 811 in 2013. Thus, the absolute numbers and incidence rates of fractures were not cohort-based estimates but complete population results, and therefore, the study, in full agreement with our previous studies [9, 10], did not use statistical analyses with confidence intervals characteristically needed for cohort- or sample-based estimations.

In the final phase of the data analysis, the above noted age-specific incidence rates of pelvic fracture in 1970–2013 were used to predict the age-specific incidence rates in the years 2020 and 2030 by a linear regression model. Then, within each age and sex group, the predicted absolute number of fractures was obtained by multiplying the aforementioned incidence by the estimated number of inhabitants based on Finnish Population Projections 2014–2030 [15].

All data analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics, version 2.2. As a register-based analysis, the study did not need ethics approval.

Results

The number of low-trauma pelvic fractures in elderly Finns aged 80 years or over increased considerably between the years 1971 and 2013, from 33 in 1970 to 1055 in 2013. The relative increase was 3097 % corresponding to an average increase of 72 % per year. Across the study period, the age-adjusted incidence of fracture also rose from 73 in 1970 to 364 in 2013, a relative increase of 399 % (9 % per year).

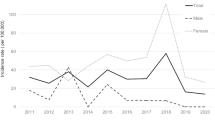

The age-specific incidence of low-trauma fractures of the pelvis also increased in all age groups of women and men during the study period (Fig. 1). In women, the injury incidence rates in 1970 were 73.0, 91.1, and 200.7 in the age groups of 80–84, 85–89, and 90–, respectively, versus 291.9, 572.2, and 812.5 in 2013. In men, the corresponding incidence rates were 8.9, 28.1, and 136.2 in 1970, versus 142.5, 281.7, and 503.2 in 2013.

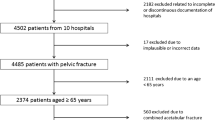

If the age-specific incidences of fracture continues to rise at the same rates as in 1970–2013 and the size of the 80-year-old or older population of Finland increases as predicted (87 % by the year 2030) [15], the number of low-trauma pelvic fractures in this population will be 2.4 times higher in the year 2030 (2550 fractures) than it was in 2013 (1055 fractures) (Fig. 2).

Discussion

The current study showed that both the number and incidence of low-trauma pelvic fractures in Finnish women and men 80 years of age or older rose steeply from 1970 to 2013 and that the rise has not declined in the new millennium. It is clear that already now the annual number of pelvic fractures in our elderly persons, among many other fracture types, represents a worrisome epidemic. Nevertheless, even more frightening is that the rising average risk of fracture and predicted increase in our ageing population are likely to accentuate the fracture development in the near future so that compared to the year 2013 Finland may have over two times more these fractures by the year 2030. A similar increase will be likely in many other developed countries, although fresh epidemiologic information from the other countries is not readily available.

Our new pelvic fracture data are in line with previous observations on the quick increase in various osteoporosis and falling-related injuries in elderly people [3–5, 10, 16] but cannot point out the exact reasons for the dramatic rise in fracture incidence. An increase in the average individual risk for osteoporosis or falling, or both, may partly explain the phenomenon, or, it may be that today older individuals have more serious consequences from falls than their predecessors [10, 16, 17]. Since we did not have individual person-years or other individual data in use (lack of date of birth and death, and lack of data on lifestyle, health, medications, nutrition, and physical activity), these issues could not be explored further. This was a clear limitation of the study. A limitation was also that our database prevented meaningful age-period-cohort modelling of the data. In hip fractures, all three mechanisms have been found to underlie the secular changes [10, 17–19].

In this context, it is of interest that in Finland and elsewhere the incidence of hip fracture has started to decline since late 1990s [18, 19]. This is in a clear contrast with the above noted rising incidence of pelvic fractures. The reasons behind this difference are unknown but it has been speculated that secular changes in the severity and mechanisms of falling of older adults could partly explain the phenomenon so that currently the biomechanics of falls could more often result in impact-loading of the pelvic ring rather than that of the proximal femur [16–18].

Altogether, the annual number of pelvic ring fractures among elderly Finnish persons is increasing with a rate that cannot be explained by demographic changes alone. For this reason, effective fracture preventing measures are needed to control the development. Good results could be obtained by focusing on reduction of the risk factors of bone loss, falls, and fractures and injury-site protection among those elderly adults who tend to fall [9, 17, 20–22].

References

Ragnarsson B, Jacobsson B (1992) Epidemiology of pelvic fractures in a Swedish county. Acta Orthop Scand 63:297–300

Luthje P, Nurmi I, Kataja M et al (1995) Incidence of pelvic fractures in Finland in 1988. Acta Orthop Scand 66:245–248

Boufous S, Finch C, Lord S, Close J (2005) The increasing burden of pelvic fractures in older people, New South Wales, Australia. Injury 36:1323–1329

Clement ND, Court-Brown CM (2014) Elderly pelvic fractures: the incidence is increasing and patient demographics can be used to predict the outcome. Eur J Orthop Surg 24:1431–1437

Nanniga GL, de Leur K, Panneman MJ, van der Elst M, Hartholt KA (2014) Increasing rates of pelvic fractures among older adults: The Netherlands, 1986-2011. Age Ageing 43:648–653

Breuil V, Roux CH, Testa J et al (2008) Outcome of osteoporotic pelvic fractures: an underestimated severity. J Bone Spine 75:585–588

Krappinger D, Kammerlander C, Hak DJ, Blauth M (2010) Low-energy osteoporotic pelvic fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 130:1167–1175

Fuchs T, Rottbeck U, Hofbauer V, Raschke M, Stange R (2011) Pelvic ring fractures in the elderly. Underestimated osteoporotic fracture. Unfallchirurg 114:663–670

Kannus P, Palvanen M, Parkkari J, Niemi S, Järvinen M (2005) Osteoporotic pelvic fractures in elderly women. Osteoporos Int 16:1304–1305

Kannus P, Parkkari J, Koskinen S et al (1999) Fall-induced injuries and deaths among older adults. JAMA 281:1895–1899

Keskimäki I, Aro S (1991) Accuracy of data on diagnosis, procedures and accidents in the Finnish hospital discharge register. Int J Health Sci 2:15–21

Sund R (2012) Quality of the Finnish Hospital Discharge Register: a systematic review. Scand J Public Health 40:505–515

Huttunen TT, Kannus P, Pihlajamäki H, Mattila VM (2014) Pertrochanteric fracture of the femur in the Finnish National Hospital Discharge Register: validity of procedural coding, external cause for injury and diagnosis. BMC Musculoskelet Dis 15:98

Official Statistics of Finland (2014) Structure of population and vital statistics: whole country and provinces, 1970–2013. Statistics Finland, Helsinki

Official Statistics of Finland (2014) Population projections by municipalities 2014–2030. Statistics Finland, Helsinki

Korhonen N, Niemi S, Parkkari J, Sievänen H, Kannus P (2013) Incidence of fall-related traumatic brain injuries among older Finnish adults between 1970 and 2011. JAMA 309:1891–1892

Kannus P, Niemi S, Parkkari J, Palvanen M, Heinonen A, Sievänen H et al (2002) Why is the age-adjusted incidence of low-trauma fractures rising in many elderly populations? J Bone Miner Res 17:1363–1367

Korhonen N, Niemi S, Parkkari J, Sievänen H, Palvanen M, Kannus P (2013) Continuous decline in incidence of hip fracture. Osteoporos Int 24:1599–1603

Stevens J, Rudd R (2010) Declining hip fracture rates in the United States. Age Ageing 39:500–503

Kannus P, Parkkari J, Niemi S et al (2000) Prevention of hip fracture in elderly people with use of a hip protector. N Engl J Med 343:1506–1513

Palvanen M, Kannus P, Piirtola M, Niemi S, Parkkari J, Järvinen M (2014) Effectiveness of the Chaos Falls Clinic in preventing falls and injuries of home-dwelling older adults: a randomized controlled trial. Injury 45:265–271

Uusi-Rasi K, Patil R, Karinkanta S et al (2015) Exercise and vitamin D in fall prevention among older women. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. Intern Med 175:703–711

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by the Competitive State Research Financing of the Expert Responsibility Area of Tampere University Hospital, Tampere, Finland (Grant 9S018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Pekka Kannus, Jari Parkkari, Seppo Niemi, and Harri Sievänen declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

The study was fully compliant with the ethical standards of medical research.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kannus, P., Parkkari, J., Niemi, S. et al. Low-Trauma Pelvic Fractures in Elderly Finns in 1970–2013. Calcif Tissue Int 97, 577–580 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-015-0056-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-015-0056-8