Abstract

Summary

We aimed to understand how patients 50 years and older decided to persist with or stop osteoporosis (OP) treatment. Processes related to persisting with or stopping OP treatments are complex and dynamic. The severity and risks and harms related to untreated clinical OP and the favorable benefit-to-risk profile for OP treatments should be reinforced.

Introduction

Older adults with fragility fracture and clinical OP are at high risk of recurrent fracture, and treatment reduces this risk by 50 %. However, only 20 % of fracture patients are treated for OP and half stop treatment within 1 year. We aimed to understand how older patients with new fractures decided to persist with or stop OP treatment over 1 year.

Methods

We conducted a grounded theory study of patients 50 years and older with upper extremity fracture who started bisphosphonates and then reported persisting with or stopping treatment at 1 year. We used theoretical sampling to identify patients who could inform emerging concepts until data saturation was achieved and analyzed these data using constant comparison.

Results

We conducted 21 interviews with 12 patients. Three major themes emerged. First, patients perceived OP was not a serious health condition and considered its impact negligible. Second, persisters and stoppers differed in weighting the risks vs benefits of treatments, where persisters perceived less risk and more benefit. Persisters considered treatment “required” while stoppers often deemed treatment “optional.” Third, patients could change treatment status even 1-year post-fracture because they re-evaluated severity and impact of OP vs risks and benefits of treatments over time.

Conclusions

The processes and reasoning related to persisting with or stopping OP treatments post-fracture are complex and dynamic. Our findings suggest two areas of leverage for healthcare providers to reinforce to improve persistence: (1) the severity and risks and harms related to untreated clinical OP and (2) the favorable benefit-to-risk profile for OP treatments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteoporosis (OP) is a chronic condition associated with increased morbidity and mortality and decreased quality of life [1, 2]. Older adults who fracture have a 20 % risk of another fracture within 1 year [1–3] and treatment with a bisphosphonate reduces this risk by 50 % [4–6]. As such, the focus of the 2010 Osteoporosis Canada Guidelines (as well as guidelines endorsed by the National Osteoporosis Foundation and the International Osteoporosis Foundation) is secondary prevention. This entails identifying patients with fragility fractures of the upper extremity, spine, or hip, ordering bone mass density (BMD) tests and offering treatment to those at the highest risk of another fracture [7–9]. Regardless of this guidance, less than 20 % of people are treated for OP in the year post-fracture [1, 2, 6, 9]. Equally worrisome, of those written a prescription for OP treatment, 30 % will not fill their prescription (primary non-adherence) [10] and of those who do fill their first prescription, at least half will stop treatment within 1 year [11, 12]. Indeed, even in the setting of a randomized trial to improve testing and treatment of OP after a fragility fracture, 18 % of those who started treatment in the intervention arm had stopped treatment within 1 year [13]. Several models address how individual factors, such as knowledge and attitudes, and social processes, including identity and support, influence behaviors [14]. However, the patient-level factors related to starting and stopping OP treatments remain relatively under studied and yet critically important to understand [15–17].

To better understand long-term persistence (and non-persistence) with OP treatments, we capitalized on participants in the Comparing Strategies Targeting Osteoporosis to Prevent Recurrent Fractures (C-STOP) trial. This trial, based on a positive pilot study [18], is currently enrolling patients with upper extremity fragility fractures in an active-comparator randomized controlled trial of nurse case management vs a multifaceted intervention directed at patients (i.e., printed materials, education, telephonic counseling) and their physicians (i.e., reminders, opinion leader endorsed guidelines). The nurse case-manager identifies and interviews patients from clinic settings (Emergency Departments and Fracture Clinics), arranges BMD tests, and offers in-person education, counseling, and guideline-based prescription treatments as needed, and then follows patients up for 1 year.

Patients in the case-manager arm of this study represented the “best-case scenario.” For example, they are relatively healthy although they have all recently suffered a fragility fracture and are all at similar risk of re-fracture based on the most recent major osteoporotic fracture and calculated FRAX with BMD scores of moderate to high risk. In addition, they all received standardized print materials with in-person counseling and were all offered treatment based upon standardized treatment algorithms [18]. In this setting of uniform care, we hypothesized we might be able to gain important and nuanced insights into patient-specific reasons for continuing or quitting OP medications. Therefore, rather than use surveys or secondary analyses of various databases as has been done previously [3, 15, 16, 19–21], we undertook a qualitative grounded theory study to understand the processes and reasoning that adults 50 years and older with recent fragility fractures go through when deciding to persist with or stop bisphosphonates in the 1-year post-fracture.

Methods

We used a grounded theory approach as outlined by Corbin and Strauss [22] to understand the processes and reasoning people engage in when deciding to persist with or stop OP medications in general, and more specifically, bisphosphonate treatment after suffering a fragility fracture of the upper extremity. Grounded theory is an inductive approach where models or concepts are “grounded” in the data collected without an a priori hypothesis. We chose to use a grounded theory approach to understand how patients approach a diagnosis of OP and how they negotiate persisting with or stopping treatment. We considered all of these patients (50 years and older with fragility fracture of the distal radius or proximal humerus and low bone mass at one or more skeletal sites) to have a clinical diagnosis of OP [23] and refer to this as OP throughout. When referring to BMD test results alone, we refer to osteopenia (T-score ≤1.0 to −2.5) or OP (T-score ≤2.5) [18, 23] and always make this distinction explicit.

Data collection and measurements

The primary study outcomes of the larger C-STOP trial were ascertained at 6 months, and the research team remained blinded to these data. That said, during 1-year follow-up of this population, we identified nurse case-management patients who had started bisphosphonate treatment at any time up to their 1-year data collection. We enrolled 150 patients in the nurse case-management arm of the larger study. Thus, all patients seen in the clinic were potentially eligible, and the only patients seen in the clinic were trial patients. We did not sample patients “randomly” for the purposes of generalizability of the results as conceptualized in quantitative research. Instead, we sampled patients based on their ability to act as key informants (i.e., someone with direct experience with the phenomenon who is able to reflect on and articulate their experience) for the purposes of transferability of the results to similar populations and contexts. At this time, we purposefully sampled patients who had started bisphosphonate treatment (by study treatment algorithm, either generic alendronate or risedronate prescribed weekly [18]) and reported whether they were still persistent with treatment at 1 year (“persisters”) or they had stopped treatment (“stoppers”). We verified all self-reported treatment data independently by using local pharmacy dispensing records.

As the study progressed, we used theoretical sampling, one of the core strategies of grounded theory [22, 24]. Theoretical sampling is responsive to the data in that the researchers sample concepts and not persons [22]. Since the nurse case-manager had met and remained in contact with all trial patients, she helped identify potential patients who could talk directly to our various emerging concepts. For example, we recruited patients diagnosed with either osteopenia or OP as defined strictly by BMD test results to elicit a deeper understanding of perceived severity, when this specific concept emerged from analysis. As well, we re-interviewed several patients as themes and concepts emerged.

A trained researcher conducted qualitative in-person interviews using a semi-structured interview guide (Appendix), which was refined as data analysis progressed. Interviews were conducted in the same location as case-management appointments at a single center and lasted up to 45 min. Interviews were digitally recorded for subsequent analysis and verified for accuracy. The University of Alberta Health Ethics Research Board approved the parent trial and this qualitative sub-study, and all subjects provided written informed consent.

Analysis

We used constant comparison to analyze the data, using open coding and memos [22, 25, 26]. One analyst (LW) identified emerging codes and concepts. The research team held regular meetings to review code definitions, emerging concepts, and memos and to refine the interview guide. We conducted data collection and analysis concurrently until theoretical data saturation [27, 28] was achieved, that is, the major concepts were well defined and explained and no new concepts or themes emerged [22]. We implemented several strategies throughout the research process to ensure rigor including methodological coherence [29], peer debriefing [24], reflective writing [22], and maintaining an audit trail [24]. Data were managed and analyzed using Atlas.ti version 7 (Berlin, Germany, Scientific Software Development GmbH) [30].

Results

From April 2014 through March 2015, we conducted 21 interviews with 12 different patients, including a second follow-up interview with the initial 9 patients to address questions that emerged through concurrent data collection and analysis. Of the 12 patients recruited, 7 persisted with bisphosphonates and 5 stopped. Treatment status was determined at the last point of contact (e.g., a patient who was a persister at her first interview but a stopper at her second interview was classified as a stopper). Of note, three patients changed their treatment status during the study. Two thirds of patients were 60 years or older, 75 % were women, 67 % had osteopenia (T-score ≤1.0) at one or more skeletal sites according to BMD testing, and 92 % had better-than-average OP-related knowledge compared with the average score (57 %) reported previously in a similar trial population [31] (Table 1). By trial design, no patient had been taking OP medications at the time of fracture.

Three major themes emerged. We provide a list of codes, sub-codes, and supplemental illustrative quotes that comprise each theme in Table 2, and we detail each theme below.

Theme 1: negligible appreciation of risk regarding severity and impact of OP

Regardless of treatment status, patients identified similar reasons for deciding to start bisphosphonates. These reasons included: (1) being advised to do so by a healthcare professional, (2) to prevent the progression of their condition or to maintain current bone health, or (3) to stay healthy.

Nonetheless, and despite the fact that all but one of these patients had better-than-average OP-related knowledge, they did not consider OP to be a serious health condition, particularly compared with other diseases like cancer. Furthermore, based on their understanding of their own BMD test results, patients (all of whom had a fragility fracture) perceived a test result of osteopenia as less serious than OP and defined it as pre- or borderline-OP, at the beginning stages of OP, or within acceptable range. In addition, patients were not concerned about their bone health or OP prior to their fracture. Many patients believed OP was a natural part of aging, especially for women, and some commented that they did not experience symptoms or feel differently because they now had an OP diagnosis.

Of particular note, patients generally perceived minimal susceptibility to the potential negative consequences of OP in the future. They believed that it was in their control to prevent future fractures by being more careful or avoiding falls. From their perspective, the fracture was their fault. However, some patients said the fracture was unavoidable or would have happened to anyone, indicating that it was not a result of compromised bone health. Generally, patients explained that an upper extremity fracture did not affect their lives substantially in the way that a hip fracture would.

Theme 2: ongoing evaluation of risks vs benefits of treatments

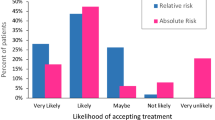

The main difference between patients who persisted with or stopped taking bisphosphonates was in their evaluation of its risks and benefits. Patients who persisted perceived greater benefit than risk from taking OP medications. They believed that medication was required or the best option to treat their condition. In addition, they perceived their risk of future fracture without OP treatment as high and said they would continue taking prescription treatment even if they had another fracture. Lastly, they did not report experiencing any side effects.

In contrast, patients who stopped treatment within 1 year believed that bisphosphonate treatment was optional and no more beneficial than exercising and taking vitamin D and calcium. They perceived their risk of future fracture without treatment as low. In addition, they reported concerns about side effects and this was enough to tip the balance towards non-persistence.

Theme 3: re-evaluation of severity and impact of OP vs risks and benefits of treatment over time

Patients reported changing (or having the potential to change) treatment status even 1-year post-fracture because they reassessed the severity and impact of OP as well as the risks and benefits of bisphosphonate treatment over time. Two patients who restarted OP medications after initially quitting explained that they have OP (rather than just osteopenia according to a BMD test) and that prescription treatment was now required rather than optional. Conversely, the patient who persisted with bisphosphonates but then stopped 1-year post-fracture explained that she had osteopenia, and not OP, according to her BMD tests and that there had been no further decline in her bone health as far as she could tell. In addition, she explained prescription treatment was but one option and not necessary to treat OP. Lastly, she reported experiencing what she perceived as side effects of bisphosphonates, including pain in her hip when laying down.

Even patients who did not change treatment status reported the potential to change status at almost any time post-fracture. For example, patients who persisted with treatment described “lapses” in adherence, primarily when traveling. One patient commented that she forgot to take her medication while traveling because OP is not life threatening. In addition, patients who persisted reported the potential to stop taking OP medications in the future if, for example, they started experiencing side effects or saw no improvement in their BMD test results. On the other hand, several patients who stopped explained that they would consider re-starting treatment in the future if, for example, they were diagnosed with OP (rather than osteopenia) based on their BMD results, believed that OP could affect their life negatively, or were informed that bisphosphonates were their best treatment option. For example, the patient who stopped prescription treatment 1-year post-fragility fracture said that she would re-start if her family physician diagnosed her with OP and told her that OP medications were required to treat it.

Discussion

In this grounded theory study examining how patients’ understand the clinical problem of OP and how they decided to persist with or stop treatment 1-year post-fracture, three broad themes emerged. First, patients perceived that OP was not a serious health condition and that its impact was negligible regardless of their decision to start treatment. Second, the main difference between persisters and stoppers was in their ongoing evaluation of the risks vs benefits of bisphosphonate treatment, where patients who persisted perceived more benefit and less risk than patients who stopped. Third, we found that patients had the potential to change treatment status even 1-year post-fracture because they re-evaluated the severity and impact of OP vs the risks and benefits of treatments over time. We have attempted to represent and conceptualize this decision-making process in Fig. 1.

According to the Information, Motivation and Behavioral Skills model [32], people are more likely to initiate and maintain health-promoting behaviors, including medication adherence [33, 34], which produce positive outcomes when they are well-informed, motivated to act, and possess the skills and confidence to take action. Perhaps the most important insight gained from our study is that even in a healthy, knowledgeable, and well-informed high-risk population with recent fragility fracture, the decision to start and then persist with long-term treatment is not a binary “yes-or-no” process situated at one point in time (i.e., the diagnostic moment). Rather, patients appear to re-evaluate and re-frame their willingness to adhere to OP medications over time based on the perceived severity and impact of OP on the one hand vs the risks and benefits of bisphosphonate treatment on the other.

The results also suggest that these risk-benefit re-assessments are driven by multiple factors related to time. First, time from the clinical fracture likely plays some role: as the memory of the clinical fracture event fades, the perceived severity diminishes. Second, the potential negative impact of OP also diminishes over time while the risks of bisphosphonate treatment become more prominent over time, particularly since the absence of another fracture is the only tangible benefit of ongoing treatment. This has implications for facilitating patient-centered decision-making [35, 36] beyond the diagnostic moment where ongoing clinical dialog is going to be needed to support persistence and to continuously re-engage patients who stop treatment. This finding is particularly relevant as demonstrated by a recent front-page article in The New York Times reporting that people tend to avoid effective osteoporosis treatment based on the fear of extremely rare side effects and calling for a more balanced perspective in weighing the favorable benefit-to-risk profile of treatment [37].

Similar to our findings, others have found that patients misunderstood their diagnosis in the context of having suffered a fragility fracture [38, 39]. As such, as suggested by an expert consensus [23], our findings indicate we should use the term “clinical OP” and refrain from using or overly emphasizing BMD test result labels such as “osteopenia” when designing patient-directed interventions or educational materials. Others have also found that patients did not consider OP serious [17, 40–42]. For example, Sale et al. found that patients did not consider compromised bone health as serious, although this perception was not related to use of OP medications [17] possibly explaining why we found this opinion common to both persisters and stoppers. In addition, other studies have commented on the challenges of appropriately treating a clinically silent disease [39, 43, 44]. Challenges related to persistence in taking long-term OP medications are not necessarily unique and seem similar to the problems with adherence and persistence demonstrated for other chronic conditions that are also “asymptomatic” such as hypertension or dyslipidemia [45, 46].

Patients may also under-estimate their fracture risk or perceive themselves as immune to the effects of OP [43]. Indeed, other studies have shown that patients believed that the fracture was unavoidable and caused by non-preventable circumstances [40, 41] and, therefore, within the realm of normal everyday occurrence. Conversely, patients may also believe the fracture was related to their own unsafe behaviors and, therefore, within their control to modify to prevent the next fracture [41, 43]. However, both of these rationalizations neglect the fact that healthy bones would not have fractured under the same low trauma circumstances.

In addition, patients appear to re-evaluate risks vs benefits of treatments for OP over time, and it is already known that patients are very concerned about possible or perceived (vs actual) side effects of bisphosphonates, and this strongly influences their decisions regarding treatment persistence [47–49]. Our work suggests that a major component of patients’ risk-benefit analysis relates to their belief about whether treatment with bisphosphonates is required (rather than “optional”) to decrease their risk of another fracture. This finding has implications for the design and content of interventions intended to promote persistence among patients who have started treatment regardless of their concerns related to potential or actual side effects. Clearly, OP medication use varies over time with patients starting, stopping, and re-initiating treatment [15, 20, 47, 50, 51]. This process of re-evaluation might be considered promising by some (because patients who stopped bisphosphonates may re-start) although others believe that it is very concerning [15, 47]. For example, Klop et al. found that persistence after re-starting OP medications remained low and was substantially lower than initial rates of persistence [15].

Despite its strengths (grounded theory approach, theoretical sampling, uniform patient population), our work has limitations. First, even by the standards of qualitative inquiry, some might consider our sample small; however, we sampled until data saturation was reached, employed multiple checks for rigor and validity, and selected participants from both ends of the persistence spectrum. Second, it was somewhat difficult to use the technique of theoretical sampling within the constraints of an ongoing trial. For example, we were unable to sample for patients who changed treatment status more than 1 year after their fracture and we had no access to patients who dropped out of the study altogether. Third, we did not set out to specifically examine sex and gender differences in health behaviors. While this is an important area of inquiry, by our grounded theory design, no sex or gender differences in pill-taking behavior were evident in our study, so we did not pursue increased sampling of constructs related to sex and gender. Last, all subjects were relatively healthy, of good socioeconomic status, had good knowledge related to osteoporosis, had no contraindications to bisphosphonate treatment, and all had an upper extremity fragility fracture, and our findings were based on the experiences of trial patients with universal healthcare coverage from one Canadian province. Thus, some might not consider our results transferrable to other populations, including patients with other types of fractures including hip or spine or settings.

The processes and reasoning related to persisting with or stopping bisphosphonate treatment for OP after a fragility fracture are complex and dynamic over the long term. Our findings suggest two potential areas to leverage for providers and those designing interventions. First, healthcare providers should reinforce the severity and risks and potential harms related to untreated clinical OP and refrain from using BMD test-based labels such as osteopenia, which appears to diminish perceived disease severity among patients. Second, healthcare providers need to review regularly the very favorable benefit-to-risk profile of treatment for this high-risk group of patients. Perhaps what has become most clear through this research is that starting treatment for OP is the beginning of a long-term negotiation with patients in an effort to prevent the next fracture and its potential consequences.

References

Little EA, Eccles MP (2010) A systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions to improve post-fracture investigation and management of patients at risk of osteoporosis. IS 5:80–97. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-5-80

Sujic R, Gignac MA, Cockerill R, Beaton DE (2011) A review of patient-centred post-fracture interventions in the context of theories of health behaviour change. Osteoporos Int 22(8):2213–2224. doi:10.1007/s00198-010-1521-x

Andrade SE, Majumdar SR, Chan KA, Buist DS, Go AS, Goodman M, Smith DH, Platt R, Gurwitz JH (2003) Low frequency of treatment of osteoporosis among postmenopausal women following a fracture. Arch Intern Med 163(17):2052–2057. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.17.2052

MacLean C, Newberry S, Maglione M, McMahon M, Ranganath V, Suttorp M, Mojica W, Timmer M, Alexander A, McNamara M, Desai SB, Zhou A, Chen S, Carter J, Tringale C, Valentine D, Johnsen B, Grossman J (2008) Systematic review: comparative effectiveness of treatments to prevent fractures in men and women with low bone density or osteoporosis. Ann Intern Med 148(3):197–213

Bolland MJ, Grey AB, Gamble GD, Reid IR (2010) Effect of osteoporosis treatment on mortality: a meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95(3):1174–1181. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-0852

Beaton DE, Sujic R, McIlroy Beaton K, Sale J, Elliot-Gibson V, Bogoch ER (2012) Patient perceptions of the path to osteoporosis care following a fragility fracture. Qual Health Res 22(12):1647–1658. doi:10.1177/1049732312457467

Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, Lewiecki EM, Tanner B, Randall S, Lindsay R (2014) Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 25(10):2359–2381. doi:10.1007/s00198-014-2794-2

International Osteoporosis Foundation (2015) Guidelines. http://www.iofbonehealth.org/content-type-semantic-meta-tags/guidelines. Accessed 20 June 2016

Papaioannou A, Morin S, Cheung AM, Atkinson S, Brown JP, Feldman S, Hanley DA, Hodsman A, Jamal SA, Kaiser SM, Kvern B, Siminoski K, Leslie WD (2010) 2010 clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in Canada: summary. CMAJ 182(17):1864–1873. doi:10.1503/cmaj.100771

Reynolds K, Muntner P, Cheetham TC, Harrison TN, Morisky DE, Silverman S, Gold DT, Vansomphone SS, Wei R, O’Malley CD (2013) Primary non-adherence to bisphosphonates in an integrated healthcare setting. Osteoporos Int 24(9):2509–2517. doi:10.1007/s00198-013-2326-5

Reginster JY, Rabenda V (2006) Adherence to anti-osteoporotic treatment: does it really matter? Futur Rheumatol 1(1):37–40

Edwards BJ, Bunta AD, Madison LD, DeSantis A, Ramsey-Goldman R, Taft L, Wilson C, Moinfar M (2005) An osteoporosis and fracture intervention program increases the diagnosis and treatment for osteoporosis for patients with minimal trauma fractures. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf/Jt Comm Resour 31(5):267–274

Majumdar SR, Johnson JA, Lier DA, Russell AS, Hanley DA, Blitz S, Steiner IP, Maksymowych WP, Morrish DW, Holroyd BR, Rowe BH (2007) Persistence, reproducibility, and cost-effectiveness of an intervention to improve the quality of osteoporosis care after a fracture of the wrist: results of a controlled trial. Osteoporos Int 18(3):261–270. doi:10.1007/s00198-006-0248-1

Whitlock EP, Orleans CT, Pender N, Allan J (2002) Evaluating primary care behavioral counseling interventions: an evidence-based approach. Am J Prev Med 22(4):267–284

Klop C, Welsing PM, Elders PJ, Overbeek JA, Souverein PC, Burden AM, van Onzenoort HA, Leufkens HG, Bijlsma JW, de Vries F (2015) Long-term persistence with anti-osteoporosis drugs after fracture. Osteoporos Int 26(6):1831–1840. doi:10.1007/s00198-015-3084-3

Majumdar SR, McAlister FA, Johnson JA, Weir DL, Bellerose D, Hanley DA, Russell AS, Rowe BH (2014) Critical impact of patient knowledge and bone density testing on starting osteoporosis treatment after fragility fracture: secondary analyses from two controlled trials. Osteoporos Int 25(9):2173–2179. doi:10.1007/s00198-014-2728-z

Sale JE, Beaton DE, Bogoch ER, Elliot-Gibson V, Frankel L (2010) The BMD muddle: the disconnect between bone densitometry results and perception of bone health. J Clin Densitom 13(4):370–378. doi:10.1016/j.jocd.2010.07.007

Majumdar SR, Johnson JA, Bellerose D, McAlister FA, Russell AS, Hanley DA, Garg S, Lier DA, Maksymowych WP, Morrish DW, Rowe BH (2011) Nurse case-manager vs multifaceted intervention to improve quality of osteoporosis care after wrist fracture: randomized controlled pilot study. Osteoporos Int 22(1):223–230. doi:10.1007/s00198-010-1212-7

Beaton DE, Dyer S, Jiang D, Sujic R, Slater M, Sale JE, Bogoch ER (2014) Factors influencing the pharmacological management of osteoporosis after fragility fracture: results from the Ontario Osteoporosis Strategy’s fracture clinic screening program. Osteoporos Int 25(1):289–296. doi:10.1007/s00198-013-2430-6

Brookhart MA, Avorn J, Katz JN, Finkelstein JS, Arnold M, Polinski JM, Patrick AR, Mogun H, Solmon DH (2007) Gaps in treatment among users of osteoporosis medications: the dynamics of noncompliance. Am J Med 120(3):251–256. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.03.029

Yood RA, Mazor KM, Andrade SE, Emani S, Chan W, Kahler KH (2008) Patient decision to initiate therapy for osteoporosis: the influence of knowledge and beliefs. J Gen Intern Med 23(11):1815–1821. doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0772-0

Corbin J, Strauss A (2008) Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory, 3rd edn. Sage Publications, Los Angeles, CA

Siris ES, Adler R, Bilezikian J, Bolognese M, Dawson-Hughes B, Favus MJ, Harris ST, Jan de Beur SM, Khosla S, Lane NE, Lindsay R, Nana AD, Orwoll ES, Saag K, Silverman S, Watts NB (2014) The clinical diagnosis of osteoporosis: a position statement from the National Bone Health Alliance Working Group. Osteoporos Int 25(5):1439–1443. doi:10.1007/s00198-014-2655-z

Mayan MJ (2009) Essentials of qualitative inquiry. Left Coast Press, Walnut Creek, California, Qualitative Essentials

Charmaz K (2006) Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage, London

Morse JM, Stern P, Corbin JM, Charmaz KC, Bowers B, Clarke AE (2008) Developing grounded theory. Left Coast Press, Walnut Creek, CA

Morse JM (2000) Determining sample size. Qual Health Res 10(1):3–5. doi:10.1177/104973200129118183

Morse JM (1994) Designing qualitative research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS (eds) The handbook of qualitative research. Sage Thousand Oaks, California, pp 220–235

Morse JM, Barret M, Mayan M, Olson K, Spier J (2002) Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods 1(2):Article 2

Scientific Software Development GmbH (2014) Atlas.ti: qualitative data analysis. http://atlasti.com/. Accessed 20 June 2016

Majumdar SR, Johnson JA, McAlister FA, Bellerose D, Russell AS, Hanley DA, Morrish DW, Maksymowych WP, Rowe BH (2008) Multifaceted intervention to improve diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis in patients with recent wrist fracture: a randomized controlled trial. Can Med Assoc J 178(5):569–575. doi:10.1503/Cmaj.070981

Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Shuper PA (2009) The information-motivation-behavioral skills model of HIV preventive behavior. In: Diclemente RJ, Crosby RA, Kegler MC (eds) Emerging theories in health promotion practice and research. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA, pp 21–63

Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Amico KR, Harman JJ (2006) An information-motivation-behavioral skills model of adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Health Psychol 25(4):462–473. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.25.4.462

Kalichman SC, Rompa D, DiFonzo K, Simpson D, Austin J, Luke W, Kyomugisha F, Buckles J (2001) HIV treatment adherence in women living with HIV/AIDS: research based on the Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills model of health behavior. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 12(4):58–67. doi:10.1016/S1055-3290(06)60217-3

Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S (2012) Shared decision making—pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med 366(9):780–781. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1109283

Institute of Medicine (IOM) (2001) Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century Washington. National Academy Press, D.C

Kolata G (2016) Osteoporosis drugs shunned for fear of rare side effects. The New York Times, June 2, 2016, p A1

Kaufman JD, Bolander ME, Bunta AD, Edwards BJ, Fitzpatrick LA, Simonelli C (2003) Barriers and solutions to osteoporosis care in patients with a hip fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am 85-A(9):1837–1843

Gardner MJ, Brophy RH, Demetrakopoulos D, Koob J, Hong R, Rana A, Lin JT, Lane JM (2005) Interventions to improve osteoporosis treatment following hip fracture. A prospective, randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 87(1):3–7. doi:10.2106/JBJS.D.02289

Meadows LM, Mrkonjic LA, Lagendyk LE, Petersen KM (2004) After the fall: women’s views of fractures in relation to bone health at midlife. Women Health 39(2):47–62. doi:10.1300/J013v39n02_04

Sale JE, Gignac MA, Frankel L, Hawker G, Beaton D, Elliot-Gibson V, Bogoch E (2012) Patients reject the concept of fragility fracture—a new understanding based on fracture patients’ communication. Osteoporos Int 23(12):2829–2834. doi:10.1007/s00198-012-1914-0

Siris ES, Gehlbach S, Adachi JD, Boonen S, Chapurlat RD, Compston JE, Cooper C, Delmas P, Diez-Perez A, Hooven FH, Lacroix AZ, Netelenbos JC, Pfeilschifter J, Rossini M, Roux C, Saag KG, Sambrook P, Silverman S, Watts NB, Wyman A, Greenspan SL (2011) Failure to perceive increased risk of fracture in women 55 years and older: the Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW). Osteoporos Int 22(1):27–35. doi:10.1007/s00198-010-1211-8

Sale JE, Beaton DE, Sujic R, Bogoch ER (2010) If it was osteoporosis, I would have really hurt myself. Ambiguity about osteoporosis and osteoporosis care despite a screening programme to educate fragility fracture patients. J Eval Clin Pract 16(3):590–596. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01176.x

Majumdar SR (2008) Recent trends in osteoporosis treatment after hip fracture: improving but wholly inadequate. J Rheumatol 35(2):190–192

Solomon DH, Iversen MD, Avorn J, Gleeson T, Brookhart MA, Patrick AR, Rekedal L, Shrank WH, Lii J, Losina E, Katz JN (2012) Osteoporosis telephonic intervention to improve medication regimen adherence: a large, pragmatic, randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 172(6):477–483. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1977

Osterberg L, Blaschke T (2005) Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med 353(5):487–497. doi:10.1056/NEJMra050100

Sale JE, Gignac MA, Hawker G, Frankel L, Beaton D, Bogoch E, Elliot-Gibson V (2011) Decision to take osteoporosis medication in patients who have had a fracture and are ‘high’ risk for future fracture: a qualitative study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 12:92. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-12-92

Che M, Ettinger B, Liang J, Pressman AR, Johnston J (2006) Outcomes of a disease-management program for patients with recent osteoporotic fracture. Osteoporos Int 17(6):847–854. doi:10.1007/s00198-005-0057-y

Miki RA, Oetgen ME, Kirk J, Insogna KL, Lindskog DM (2008) Orthopaedic management improves the rate of early osteoporosis treatment after hip fracture. A randomized clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 90(11):2346–2353. doi:10.2106/JBJS.G.01246

Melo M, Qiu F, Sykora K, Juurlink D, Laupacis A, Mamdani M (2006) Persistence with bisphosphonate therapy in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc 54(6):1015–1016. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00758.x

Weiss TW, McHorney CA (2007) Osteoporosis medication profile preference: results from the PREFER-US study. Health Expect 10(3):211–223. doi:10.1111/j.1369-7625.2007.00440.x

Ailinger RL, Harper DC, Lasus HA (1998) Bone up on osteoporosis. Development of the facts on osteoporosis quiz. Orthop Nurs 17(5):66–73

Acknowledgments

SRM holds the Endowed Chair in Patient Health Management funded by the Faculties of Medicine and Dentistry and Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences of the University of Alberta. JAJ is a Senior Scholar with Alberta Innovates-Health Solutions (AIHS) and a Centennial Professor at the University of Alberta. FAM holds the Endowed Chair in Cardiovascular Outcomes Research at the University of Alberta and is a Senior Health Scholar of AIHS. LAB is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) as a New Investigator and by AIHS as a Population Health Investigator. BHR is a Tier I Canada Research Chair in Evidence-Based Emergency Medicine supported by CIHR and Government of Canada (Ottawa, ON). This work was supported by peer-reviewed grants from the AIHS Partnership for Research and Innovation in the Health System and Alberta Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wozniak, L.A., Johnson, J.A., McAlister, F.A. et al. Understanding fragility fracture patients’ decision-making process regarding bisphosphonate treatment. Osteoporos Int 28, 219–229 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-016-3693-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-016-3693-5