Abstract

Summary

We evaluated the association between bisphosphonate use and (1) upper gastrointestinal cancer, (2) upper endoscopy, (3) incident Barrett’s esophagus, and (4) prescription antacid initiation among Medicare beneficiaries. We found no bisphosphonate-cancer association and negative bisphosphonate-Barrett’s association.

Introduction

Bisphosphonates can irritate the esophagus; a cancer association has been suggested. Widespread bisphosphonates use compels continued investigation of upper gastrointestinal toxicity.

Methods

Using a 40 % Medicare random sample denominator, inpatient, outpatient (2003–2011), and prescription (2006–2011) claims, we studied patients age 68 and older with osteoporosis and/or oral bisphosphonate use. Inverse propensity weighting estimated marginal structural models for the effect of bisphosphonate intensity (pills per month) and cumulative bisphosphonate pills received on upper gastrointestinal cancer risk. Secondary analyses of sub-cohorts without past bisphosphonates or upper endoscopy assessed bisphosphonate initiation and risk of (1) upper endoscopy, (2) incident Barrett’s esophagus, and (3) prescription antacid initiation.

Results

The cohort included 1.64 million beneficiaries: 87.9 % women, mean age, 76.8 (standard deviation (SD) 9.3); mean follow-up, 39.6 months; 38.1 % received oral bisphosphonates. Cumulative bisphosphonate receipt, among users, ranged from 4 to 252 pills (5th to 95th percentile). We identified 2,308 upper gastrointestinal cancers (0.43/1000 person years). We found no association between cumulative bisphosphonate pills and cancer, odds ratio (OR) for each additional pill 1.00 (95 % confidence interval (CI) 1.00, 1.00). In sub-cohorts, compared to none, lowest cumulative bisphosphonate use (one to nine pills) was associated with higher risk of endoscopy (OR 1.11, 95 % CI 1.08–1.14) and antacid initiation (OR 1.13, 95 % CI 1.10–1.16); higher intensity conferred no increased risk. Higher intensity and higher cumulative bisphosphonate category were associated with lower Barrett’s risk.

Conclusions

We found no bisphosphonate-cancer association and negative bisphosphonate-Barrett’s association. Bisphosphonate initiation appears to identify patients susceptible to early irritating effects; clinicians might offer alternatives and delay endoscopy or antacids.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Studies to date on the association between oral bisphosphonates and esophageal cancer have drawn conflicting conclusions [1–12]. The divergent literature has been well summarized [12–14]. Case reports and studies have linked esophageal cancer cases to oral bisphosphonate use (especially nitrogen-containing alendronate) after relatively brief exposures [2, 5, 6, 13]. Others have found no such association [1, 15, 16]. A study of National Registers data from Denmark found bisphosphonates protective against esophageal cancer; the authors reasoned that greater use of endoscopy before initiation of bisphosphonates may explain the apparent protective effect, by essentially pre-screening potential users [17]. In contrast, some suggest that esophageal irritation by bisphosphonates may prompt endoscopy and result in either earlier stage tumor diagnosis or cancer over-diagnosis, explaining reports of higher cancer risk associated with bisphosphonates [2].

The unsettled relationship between oral bisphosphonates and cancer and the equally unsettled role of endoscopy in identifying treatment-appropriate patients or detecting cancer early compels further investigation of the effects of bisphosphonates on the esophagus. Guidelines and quality measures encourage use of bisphosphonates, and the target treatment population, largely the elderly, is growing. As a consequence, understanding risks associated with bisphosphonate use is increasingly important.

We aimed to advance understanding of the potential esophageal toxicity of bisphosphonates in four distinct ways. First, we assessed bisphosphonate exposure with greater precision than past observational studies; specifically, we quantified exposure by pill count rather than prescriptions received which permits examination of the most relevant, potential dose-response relationship. Cancer promotion by oral bisphosphonates is hypothesized to result from injury and inflammation arising from contact between pills and the esophageal mucosa [18–25]. For this class of medications, prescription count may be an especially imprecise measure of exposure. Dosing frequencies range from daily to monthly pills or 12 to 365 pills per year for the perfectly adherent patient. The range of intended supply per prescription can vary substantially, from 30 to 90 days in general, so one prescription could represent as few as one and as many as 90 pills. Secondly, we assessed the association between bisphosphonate initiation and receipt of upper endoscopy to explore the relationship between this drug class and this test in the pathway of esophageal cancer diagnosis. Thirdly, we assessed the relationship between bisphosphonate initiation and prescription antacid initiation (proton pump inhibitors and histamine two receptor antagonists (PPIs/H2RAs)) as a proxy measure of esophageal symptoms and clinician tendency to treat those symptoms. Lastly, we assessed the relationship between bisphosphonate pills and incident diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus, a result of mucosal injury and a precursor to one type of esophageal cancer.

Methods

Data and cohort

We used a 40 % Medicare random sample denominator file and corresponding Medicare claims from Parts A (inpatient insurance) and B (outpatient insurance) for 2003–2011 and Part D (prescription insurance) for 2006–2011, to identify osteoporosis/osteopenia patients. Patients were included in the study if they (1) received one or more inpatient or outpatient diagnosis of osteoporosis/osteopenia between 2003 and 2009 or (2) received one or more prescription fills for an oral bisphosphonate from 2006 to 2009. Patients meeting the initial inclusion criteria were further required to: (1) be enrolled in the Medicare Part D prescription drug program for 12 or more consecutive months following achievement of the above inclusion criteria, (2) be 68 or older at the beginning of the 12 consecutive months of Part D enrollment, and (3) have at least 30 months of continuous fee-for-service Parts A and B enrollment immediately preceding the 12 months of the continuous Part D enrollment, to permit ascertainment of pre-observation co-morbidity and esophageal disease status. Patients with cancer diagnoses were excluded; this was defined as at least one inpatient or two outpatient diagnoses of cancer (other than non-melanoma skin) during the 30-month look back or during the first 6 months of Part D observation (collectively 36 months total look back for morbidities). Patients diagnosed with Paget’s disease were also excluded. See Appendix Table 1 for specific diagnosis codes and drugs.

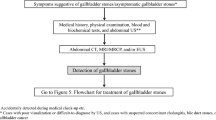

From this main cohort, two sub-cohorts were created for secondary analyses: sub-cohort A: patients who were naive to upper endoscopy, to serious gastrointestinal diagnoses (Barrett’s esophagus or peptic ulcer disease) and to oral bisphosphonate use at the beginning of follow-up, and sub-cohort B: a sub-set of sub-cohort A also naive to prescription PPI/H2RA use. Naïve status was based on the 36-month look back of non-prescription claims and on the first 6 months of prescription claim records for bisphosphonate and PPI/H2RA use. See Appendix Fig. 1 for study framework and Appendix Table 1 for procedure codes used to identify upper endoscopy.

Exposure

Oral bisphosphonate exposure was measured from the Part D prescription fill records using the number of pills dispensed in each calendar quarter (3-month period). Number of pills was used rather than dose because this most closely estimates proposed mechanism of injury, namely, pill-esophagus contact events. For each 90-day period, each patient was assigned a bisphosphonate intensity category based on pills received each quarter and a cumulative exposure count representing total observed bisphosphonate pills received up to that quarter. Prescription fills for the non-bisphosphonate anti-resorptive drug calcitonin were also recorded for each 3-month period as an indicator of treatment-worthy low bone density. Initial exploratory analyses assessing the distinct bisphosphonate molecules received by patients revealed relatively low product loyalty; thus, no product-specific (e.g., alendronate) analyses were attempted. Overall, more than 99 % of all bisphosphonate pills dispensed were, like alendronate, nitrogen containing, so findings reflect outcome associated with this group of bisphosphonates, the group previously associated cancer risk [24, 25]. Appendix Table 2 displays the distribution of bisphosphonate use frequency by molecule (overall 67 % alendronate, 32 % risedronate).

Outcomes

The primary outcome of interest was incident esophageal cancer, specifically distal esophageal cancer, the type hypothesized to be associated with oral bisphosphonates. Administrative data, however, are not well suited to accurately distinguish precise anatomic location of esophageal cancer (e.g., distal from proximal) or even upper gastric from lower esophageal cancer. To address this limitation and to maximize comparability of our study with others, we defined our principal outcome as the composite of incident esophageal or gastric cancer (included because upper gastric cancer may be poorly distinguished from lower esophageal). This was defined as one inpatient or two outpatient diagnoses of these cancer types (see Appendix Table 1 for ICD-9 codes). Sensitivity analyses examined esophageal cancer outcomes distinctly. Secondary analyses examined the association between oral bisphosphonate initiation and three distinct outcomes: (1) receipt of upper endoscopy, (2) initiation of a prescription antacid (proton pump inhibitor or histamine-2 receptor antagonist (PPI/H2RA)), or (3) incident Barrett’s esophagus disease, defined as one inpatient or two outpatient diagnoses (see Appendix Table 1).

Covariates

Covariates included age (at beginning of Part D prescription claim observation), gender, race (categorized as Black, Hispanic, other based on Medicare denominator file variable), and Medicare Part D low-income subsidy (marker for income 150 % or less of federal poverty level) [26]. The following comorbidities, diagnosed once or more at any time in the 30-month look back, were also included: Barrett’s esophagus, other esophageal and gastrointestinal diseases, alcohol abuse, chronic obstructive lung disease and/or tobacco use (combined as “tobacco exposure” proxy variable), obesity, and Charlson comorbidities not otherwise excluded or included [27]. We created indicator variables for one or more prescription fill of antacid (PPI or H2RA) in the 6-month prescription claim look back. We included the following variables in models as time-varying covariates due to their potential to influence bisphosphonate use: bone density testing, fragility fracture diagnosis, and receipt of institutional care (defined as ≥50 % of fills dispensed by a long-term-care pharmacy in one or more quarter). For secondary analyses, two additional time-varying, drug-use covariates were included due to their potential to influence receipt of upper endoscopy or prescription antacid initiation: (1) prescription non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and (2) Cox-II-selective NSAIDs; use was based on Part D claims and classified dichotomously for each 3-month period.

Analysis

The risk of upper gastrointestinal cancer associated with oral bisphosphonate receipt was studied using a marginal structural model estimated with inverse propensity weights (IPWs) [28]. Propensities were derived for each 3-month period for each patient based on a logistic regression model for the effect of individual characteristics or events on bisphosphonate dose intensity category (pills per 3-month period categorized based on natural data breaks as follows: no exposure, 1–3 pills, 4–12 pills, and 13 or more pills). Time-varying disease diagnosis covariates listed above were managed as irreversible states (i.e., once a fragility fracture patient, always a fragility fracture patient), whereas time-varying drug use was permitted to flux for each patient in each 3-month period. In separate analyses, cancer risk was modeled on category of cumulative bisphosphonate pills received. This was done to test for a threshold effect of pills received and also to make our analyses comparable to other studies using thresholds of prescription fills as the exposure of interest. These secondary cancer models and all models on secondary outcomes were estimated using logistic regression with time-varying exposure and disease state categories without IPW, because the principal exposure of interested was cumulative bisphosphonate pills for which a propensity weighting approach was not feasible. This approach of logistic regression is sometimes referred to as pooled logistic regression and has an equivalence to hazard ratio estimation using Cox’s model with time-dependent covariates [29]. The odds ratios that we estimate are a very close approximation of the cause-specific hazard ratio of Cox’s model. The Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at Dartmouth College approved this study.

Results

Overall, 1.6 million patients met cohort inclusion criteria; mean age at time of cohort entry was 76.8 (standard deviation (SD) 9.3); 87.9 % were women, 91.0 % were non-Black/non-Hispanic, and 40.6 % received low-income subsidy; follow-up time for main models was 39.6 months (SD 21.0). Preceding the start of observation, 23.9 % received a prescription PPI and 6.0 % an H2RA (based on 6-month look back) and 17 % had undergone upper endoscopy. The two sub-cohorts had similar characteristics. The endoscopy outcome sub-cohort (sub-cohort A) included 880,205 patients (53.7 % of full cohort); mean follow-up was 38.5 months (SD 20.8). The prescription antacid (PPI/H2RA) initiation sub-cohort (sub-cohort B) included 682,289 patients (44.0 % of full cohort); mean follow-up was 39.0 months (SD 20.8) (Table 1).

Crude outcomes and exposures are described in Table 2. Overall, 38.1 % used some oral bisphosphonate; cumulative bisphosphonate receipt among users ranged from 4 to 252 pills; 20.2 % of the cohort received more than 50 pills. We observed 2,308 incident gastric or esophageal cancer cases (0.43/1,000 person years). Cancer rates in the clean-look-back sub-cohorts did not differ substantially from rates of the overall cohort. Among members of the clean-look-back endoscopy outcome sub-cohort A, 14.9 % underwent at least one upper endoscopy. Among members of the PPI/H2RA initiation sub-cohort B, 28.8 % initiated one or more of these prescription antacids.

Main models on cancer outcomes

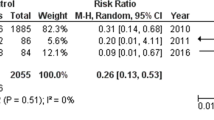

We found no association with cumulative bisphosphonate pills (as a continuous variable), OR associated with one additional pill 1.00 (95 % confidence interval (CI) 1.00, 1.00). Similarly, cancer risk associated with each bisphosphonate use intensity category (pills per 3-month period) was not different from no use. Cancer risk was higher in each older age stratum and, as expected, among those diagnosed with alcohol abuse, tobacco exposure, and among those with past upper endoscopy (Table 3). In models that were not weighted, compared to no bisphosphonate use, no category of cumulative bisphosphonate pills received was associated with an increased risk of upper gastrointestinal cancer, OR for the highest exposure group (50 or more pills) 1.11 (95 % CI 0.88, 1.39) (Fig. 1) (Table 4). A sensitivity analysis modeling bisphosphonate exposure and esophageal cancer cases only (rather than esophageal and gastric) revealed no significant association (data not shown).

Secondary models restricted to sub-cohort A

Models restricted to sub-cohort A assessed the relationship between bisphosphonate exposure and two distinct outcomes: (1) receipt of upper endoscopy and (2) Barrett’s esophagus diagnosis. Models assessing endoscopy risk revealed no difference associated with increased intensity of pill receipt (Table 3), but a higher risk among patients in the lowest category of cumulative use (one to nine pills) (OR 1.11; 95 % CI 1.08, 1.14) (Table 4). Models assessing risk of Barrett’s esophagus diagnosis revealed a negative association with pill use intensity, OR associated with 13 or more pills per quarter 0.38 (95 % CI 0.18, 0.80) (Table 3). Models assessing risk of Barrett’s and category of cumulative exposure similarly revealed a negative association, OR associated with receiving 50 or more pills 0.56 (95 % CI 0.39, 0.79) (Table 4).

Secondary models restricted to sub-cohort B

Models assessing sub-cohort B and risk of prescription antacid initiation showed, compared to no use, no increased risk associated with higher pill intensity, OR associated with 13 or more pills per quarter 0.94 (95 % CI 0.88, 1.01) (Table 3). Models assessing category of cumulative exposure revealed the highest risk of prescription antacid initiation associated with the lowest cumulative exposure, OR associated with one to nine pills, 1.13 (95 % CI 1.10, 1.16) (Table 4). In these sub-cohort models, risk of antacid initiation associated with bisphosphonate use was dwarfed by risk associated with use of COX-2-selective and non-selective NSAIDs (Tables 3 and 4).

Discussion

Our study of an older American, predominantly female cohort found no association between oral bisphosphonates and upper gastrointestinal cancer. We find a negative association between bisphosphonate use and Barrett’s esophagus. Our discovery that endoscopy and prescription antacid initiation were most likely among those with the lowest cumulative bisphosphonate exposure (compared to those with no exposure and relative to those with the most exposure) suggests that early bisphosphonate use identifies patients susceptible to irritating pill effects; these findings have distinct clinical implications and expand current knowledge on toxicity of oral bisphosphonates.

Overall, the study cohort appears representative of the general, older, Medicare population, experiencing only modestly higher rates of each outcome measured. The rate of esophageal cancer that we observed (17 per 100,000 person years) is similar to that reported for this age group by the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program which includes more clinically detailed data (11 to 17 per 100,000 person years for women) [30]. The rate of prescription antacid initiation observed in sub-cohort B (25.3 % for PPI and 7.4 % for H2RA) was similar to the 2010 prevalence of the use of these medications in the general fee-for-service, Medicare Part D population (25.8 % PPI and 6.7 % H2RA, authors’ Medicare data analysis) [31]. The observed rates of upper endoscopy (5.0 % per year) were modestly higher than those reported generally among Medicare enrollees 2004–2006, 12 % over 3 years, or approximately 4 % per year [32].

Our finding of no relationship between upper gastrointestinal cancer and bisphosphonate receipt echoes the growing body of literature reassuring patients and clinicians on this aspect of bisphosphonate safety [1, 4, 9, 15–17]. The distinct features of our study advance the collective understanding of the impact of bisphosphonates on esophageal cancer risk. Our cohort had substantial bisphosphonate exposure (38 % with some use), and we measured this exposure in pills dispensed, rather than prescription fills, which should closely reflect pill-esophageal contact events, the proposed mechanism of injury, and cancer promotion. Our study controlled for receipt of upper endoscopy in the 3 years preceding start of observation and thus separated this factor from bisphosphonate exposure. Our cohort is older than that of other studies but reflects the age group most commonly prescribed this class of medications. Our exposure time and follow-up time were similar to previous studies with both positive and negative findings [1, 2, 9].

The higher risk of endoscopy or antacid prescription receipt among a subset of incident bisphosphonate users after relatively little cumulative exposure may have important clinical implications. We believe that this reveals a group of patients especially susceptible to the esophageal side effects of oral bisphosphonates. After few pills, they are more likely to get endoscopic evaluation and/or be treated for esophageal disease or symptoms. While this finding may result from scant bisphosphonate use unmasking gastro-esophageal pathology that prompts treatment discontinuation in some, our failure to find an association between bisphosphonate use and significant esophageal pathology instead suggests individual-level differences in ability to tolerate these pills and a tendency for these symptoms to trigger endoscopy and prescription antacid treatment by US clinicians. Our findings parallel those of a Denmark registry study that found twofold higher frequency of upper endoscopy among subjects in the year after beginning alendronate treatment (4.5 versus 2.1 % in control (p < 0.001) [17].

In contrast, to these susceptible patients, greater cumulative use of bisphosphonates appears a marker of lower likelihood of endoscopy and antacid initiation, suggesting a relatively tolerant sub-population makes up the patients with the greatest use of these products. This may explain the “protective” effect of bisphosphonates observed by other studies assessing cancer outcome risks and the negative association that we observed with Barrett’s esophagus outcomes, namely, a healthy user bias [4, 16].

Clinically, patients susceptible to pill effects and early endoscopy or antacid prescription may be an important group to identify and to manage differently, either with especially judicious use of bisphosphonates, early consideration of intravenous bisphosphonates, or bisphosphonate alternatives. Importantly, our inability to identify significant esophageal pathology as a result of bisphosphonate exposure argues for a conservative approach to endoscopy and prescription therapy in the year following bisphosphonate initiation. A trial off of oral bisphosphonates and reassessment of symptoms may be the best initial approach. Identifying this population and optimal management of their low bone density as well as their bisphosphonate-associated esophageal symptoms will require robust risk benefit analysis.

Our claims-based study has important limitations. Osteopenia/osteoporosis has both known and unknown etiologies. Well-documented risk factors include tobacco use, poor nutrition, genetic predisposition, under weight, and hormone status. In this observational study, we are unable to ascertain many of these factors that may also be associated with esophageal cancer risk. We are equally unable to observe unknown risk factors. To address this limitation, we define our study cohort by disease state (osteopenia/osteoporosis diagnosis or bisphosphonate receipt). This approach creates a relatively homogeneous cohort of patients with relatively similar unobservable potential risk factors. While we believe this as the best approach, it is possible that untreated osteoporosis/osteopenia patients are substantially different from treated patients with the same diagnosis, creating a biased comparison.

The Medicare Part D program was initiated on January 1, 2006, and we have no prescription use data preceding this date; thus, our exposure measurement is left truncated, and observed cumulative exposure may underestimate full cumulative exposure in long-term bisphosphonate users. Bisphosphonates are administered intravenously, but in our data, use of this drug form was insufficient to permit study (<1 % of the cohort). Low product loyalty also made molecule-specific exposure modeling unfeasible; nearly all exposure (measured as pill count) was alendronate, but our models may miss differential effect of risedronate, which accounted for 32 % of all pills received. We depend on diagnosis codes for identification of prevalent and incident disease as well as comorbidities. While researchers have validated use of diagnostic codes in other datasets for the ascertainment of incident esophageal cancer cases, we are aware of no such validation studies specific to Medicare claims [33, 34]. Our study thus is limited by the accuracy of the recorded codes. We also have only diagnosis-based data on key esophageal cancer risk factors, tobacco use, and alcohol use. This is an important limitation. We also rely on diagnosis codes for the comorbidity obesity, a risk factor for reflux disease that might trigger endoscopy and/or prescription antacid initiation. Our exposure measurement reflects pills received rather than pills ingested and thus risks misclassifying exposure for patients not taking pills received, though financial incentives such as prescription co-payments should limit fills not consumed. Our mean follow-up of 39.6 months for cancer outcomes, while comparable to some other studies, may be insufficient to detect longer latency cancer-related toxicity.

Conclusion

Our study adds to the literature reassuring patients and clinicians about the safety of bisphosphonates with respect to esophageal cancer risks. Our results also suggest reports by others of a protective effect of bisphosphonates likely stems from a healthy user bias. Our findings of an especially susceptible sub-cohort likely to undergo endoscopy and/or prescription antacid initiation after relatively few pills, combined with the lack of association between oral bisphosphonates and significant esophageal disease, suggest the need for careful oral treatment selection and a conservative approach to gastrointestinal symptoms that follow scant pill use. Future studies should seek to identify predictors of poor oral bisphosphonate tolerance so that these patients might be offered alternatives earlier. Additionally, studies aimed at quantifying the cost-effectiveness of oral bisphosphonates should include the risk and cost associated with higher rates of upper endoscopy following initiation.

References

Cardwell CR, Abnet CC, Cantwell MM, Murray LJ (2010) Exposure to oral bisphosphonates and risk of esophageal cancer. JAMA: J Am Med Assoc 304:657–663

Green J, Czanner G, Reeves G, Watson J, Wise L, Beral V (2010) Oral bisphosphonates and risk of cancer of oesophagus, stomach, and colorectum: case-control analysis within a UK primary care cohort. BMJ 341

Nguyen DM, Schwartz J, Richardson P, El-Serag HB (2010) Oral bisphosphonate prescriptions and the risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma in patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Dig Dis Sci 55:3404–3407

Ho YF, Lin JT, Wu CY (2012) Oral bisphosphonates and risk of esophageal cancer: a dose-intensity analysis in a nationwide population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 21:993–995

Wysowski DK (2009) Reports of esophageal cancer with oral bisphosphonate use. N Engl J Med 360:89–90

Wysowski DK (2010) Oral bisphosphonates and oesophageal cancer. BMJ 341

Rozenberg S, Dutton S (2011) Bisphosphonates and oesophageal cancer risk: where are we now? Maturitas 68:106–108

Lee WY, Sun LM, Lin MC, Liang JA, Chang SN, Sung FC, Muo CH, Kao CH (2012) A higher dosage of oral alendronate will increase the subsequent cancer risk of osteoporosis patients in Taiwan: a population-based cohort study. PLoS ONE 7

Vinogradova Y, Coupland C, Hippisley-Cox J (2013) Exposure to bisphosphonates and risk of gastrointestinal cancers: series of nested case-control studies with QResearch and CPRD data. BMJ 346

Oh YH, Yoon C, Park SM (2012) Bisphosphonate use and gastrointestinal tract cancer risk: meta-analysis of observational studies. World J Gastroenterol: WJG 18:5779–5788

Sun K, Liu JM, Sun HX, Lu N, Ning G (2013) Bisphosphonate treatment and risk of esophageal cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Osteoporos Int 24:279–286

Wright E, Schofield PT, Seed P, Molokhia M (2012) Bisphosphonates and risk of upper gastrointestinal cancer--a case control study using the General Practice Research Database (GPRD). PLoS ONE 7:e47616

Haber SL, McNatty D (2012) An evaluation of the use of oral bisphosphonates and risk of esophageal cancer. Ann Pharmacother 46:419–423

Pazianas M, Abrahamsen B (2011) Safety of bisphosphonates. Bone 49:103–110

Solomon DH, Patrick A, Brookhart MA (2009) More on reports of esophageal cancer with oral bisphosphonate use. N Engl J Med 360:1789–1790, author reply 1791-1782

Abrahamsen B, Eiken P, Eastell R (2009) More on reports of esophageal cancer with oral bisphosphonate use. N Engl J Med 360:1789, author reply 1791-1782

Abrahamsen B, Pazianas M, Eiken P, Russell RG, Eastell R (2012) Esophageal and gastric cancer incidence and mortality in alendronate users. J Bone Miner Res 27:679–686

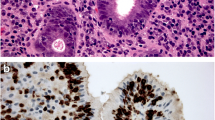

Abraham SC, Cruz-Correa M, Lee LA, Yardley JH, Wu TT (1999) Alendronate-associated esophageal injury: pathologic and endoscopic features. Mod Pathol 12:1152–1157

Ribeiro A, DeVault KR, Wolfe JT 3rd, Stark ME (1998) Alendronate-associated esophagitis: endoscopic and pathologic features. Gastrointest Endosc 47:525–528

Singh SP, Odze RD (1998) Multinucleated epithelial giant cell changes in esophagitis: a clinicopathologic study of 14 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 22:93–99

Marshall JK, Thabane M, James C (2006) Randomized active and placebo-controlled endoscopy study of a novel protected formulation of oral alendronate. Dig Dis Sci 51:864–868

Marshall JK, Rainsford KD, James C, Hunt RH (2000) A randomized controlled trial to assess alendronate-associated injury of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 14:1451–1457

Lanza FL, Hunt RH, Thomson AB, Provenza JM, Blank MA (2000) Endoscopic comparison of esophageal and gastroduodenal effects of risedronate and alendronate in postmenopausal women. Gastroenterology 119:631–638

Thomson AB, Marshall JK, Hunt RH, Provenza JM, Lanza FL, Royer MG, Li Z, Blank MA (2002) 14 day endoscopy study comparing risedronate and alendronate in postmenopausal women stratified by Helicobacter pylori status. J Rheumatol 29:1965–1974

Peter CP, Handt LK, Smith SM (1998) Esophageal irritation due to alendronate sodium tablets: possible mechanisms. Dig Dis Sci 43:1998–2002

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2008) Creation of new race-ethnicity codes and socioeconomic status (SES) indicators for Medicare beneficiaries. US Department of Health & Human Resources. http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/medicareindicators/medicareindicators2.htm. Accessed April 23 2010

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chron Dis 40:373–383

Hernan MA, Brumback B, Robins JM (2000) Marginal structural models to estimate the causal effect of zidovudine on the survival of HIV-positive men. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass) 11:561–570

D’Agostino RB, Lee ML, Belanger AJ, Cupples LA, Anderson K, Kannel WB (1990) Relation of pooled logistic regression to time dependent Cox regression analysis: the Framingham Heart Study. Stat Med 9:1501–1515

National Cancer Institute S, Epidemiology, and End Results Program, (2014) Cancer of the esophagus (invasive), SEER incidencea and U.S. deathb rates, age-adjusted and age-specific rates, by race and sex. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2011/browse_csr.php?sectionSEL=8&pageSEL=sect_08_table.07.html. Accessed September 17 2014

Munson JC, Morden NE (2013) The Dartmouth Atlas of Medicare Prescription Drug Use

Pohl H, Robertson D, Welch HG (2014) Repeated upper endoscopy in the Medicare population: a retrospective analysis. Ann Intern Med 160:154–154

Dregan A, Moller H, Murray-Thomas T, Gulliford MC (2012) Validity of cancer diagnosis in a primary care database compared with linked cancer registrations in England. Population-based cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol 36:425–429

Walker AM (2011) Identification of esophageal cancer in the General Practice Research Database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 20:1159–1167

Funding

National Institutes on Aging K23AG035030 (Morden) and P01 AG019783

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Dartmouth Atlas Project

National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases P60AR062799

Conflicts of interest

Nancy E. Morden, Jeremy Smith, Todd A. Mackenzie, Stephen K. Liu, and Anna N A Tosteson declare that they have no conflict of interest. Dr. Munson received payment from GlaxoSmithKline for consulting on the design and analysis of a research study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix Table 1

(DOCX 87 kb)

Appendix Table 2

(DOCX 57 kb)

Appendix Figure 1

(PDF 55 kb)

Appendix Figure 2

(DOCX 97 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Morden, N.E., Munson, J.C., Smith, J. et al. Oral bisphosphonates and upper gastrointestinal toxicity: a study of cancer and early signals of esophageal injury. Osteoporos Int 26, 663–672 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-014-2925-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-014-2925-9