Abstract

Two centuries of continuous economic growth since the industrial revolution have fundamentally transformed consumer lifestyles. Here Keynes raised an important question: will consumption always continue to expand in the same manner as it has in the previous two centuries? If so, how? This paper critically reviews a body of work that has adopted the Learning To Consume (LTC) approach to study the long run growth of consumption (Witt 2001). By borrowing certain established insights from psychology and biology about how consumers learn and what motivates them to consume, it highlights how rising income, new technologies and market competition have combined to trigger important changes in both the underlying set of needs possessed by consumers and how they learn to satisfy these needs. Methodological issues and open questions are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Note that it is assumed that each need precisely corresponds to one expenditure category. Thus j is not present in the formula, since i = j.

These learning modes coexist because the enlargement of human brain capacity did not evolve in a way in which there was a smooth substitution of more advanced learning mechanisms for more primitive ones (Flinn 1997:33, Sartorius 2003). Rather, development was sticky: more advanced mechanisms emerged to complement older mechanisms. This presence of two learning systems is also recognized in dual process theory (Gigerenzer et al. 1999; Kahneman 2003).

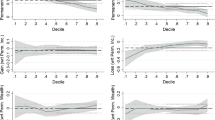

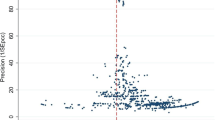

In addition, note that making inferences about individual behaviour from such Engel curves assumes that the aggregation process does not substantially influence the shape of Engel curves. Many other factors may influence the shape of Engel curves, such as how consumers change the manner in which they learn from their peers as they become more affluent (Cordes 2009).

Elsewhere, the acquisition of preferences is also shaped by families and the socialization process (Volland 2013) and the availability of (non-working) time (Chai et al. 2015).

The key to progress on this issue is to recognize that different modes of behavior coexist (e.g. Hayek 1960; Gigerenzer et al. 1999; Witt 2001; Kahneman 2003) and to identify how agents may transition between modes and the different circumstances in which these modes tend to dominate (Brenner 1999; Lades 2014).

References

Adner R, Levinthal D (2001) Demand heterogeneity and technology evolution: implications for product and process innovation”. Manag Sci 47:611–628

Alhadeff D (1982) Microeconomics and human behavior: toward a new synthesis of economics and psychology. University of California Press, Berkeley

Anderson J (2000) Learning and memory. Wiley, New York

Aoki M, Yoshikawa H (2002) Demand saturation-creation and economic growth. J Econ Behav Organ 48(2):127–154

Aversi R, Dosi G, Fagiolo G, Meacci M, Olivetti C (1999) Demand dynamics with socially evolving preferences. Ind Corp Chang 8:2

Babutsidze Z (2011) Returns to product promotion when consumers are learning how to consume. J Evol Econ 21(5):783–801

Banerjee AV, Duflo E (2007) The economic lives of the poor. J Econ Perspect 21(1):141–168

Barigozzi M, Moneta A (2011) The rank of a system of engel curves: how many common factors? (No. 1101). Papers on economics and evolution

Baudisch AF (2007) Consumer heterogeneity evolving from social group dynamics: latent class analyses of German footwear consumption 1980–1991”. J Bus Res 60(8):836–847

Bernheim BD, Rangel A (2004) Addiction and cue-triggered decision processes. Am Econ Rev 1558–1590

Berridge KC, Robinson TE, Aldridge JW (2009) Dissecting components of reward:‘liking’, ‘wanting’, and learning. Curr Opin Pharmacol 9(1):65–73

Bertola G, Foellmi R, Zweimüller J (2006) Income distribution in macroeconomic models. Princeton University Press, Cambridge

Bianchi M (1998) Taste for novelty and novel tastes. In: Bianchi M (ed) The active consumer: Novelty and surprise in consumer choice. Routledge, London, pp. 64–86

Bianchi M (2002) Novelty, preferences and fashion: when new goods are unsettling. J Econ Behav Org 47:1–18

Bils M, Klenow PJ (2001b) The acceleration in variety growth. Am Econ Rev 91(2):274–280

Binder M (2010) Elements of an evolutionary theory of welfare: assessing welfare when preferences change. Routledge

Boppart T (2014) Structural change and the Kaldor facts in a growth model with relative price effects and non‐Gorman preferences. Econometrica 82(6):2167–2196

Bouis HE, Haddad LJ (1992) Are estimates of calorie-income fxelasticities too high?: a recalibration of the plausible range. J Dev Econ 39(2):333–364

Bowles S (1998) Endogenous preferences: the cultural consequences of markets and other economic institutions. J Econ Lit 36:75–111

Brenner T (1999) Modeling learning in economics. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Bresnahan T, Gambardella A (1998) The division of inventive labor and the extent of the market. In: Helpman E (ed) Genral purpose technologies and economic growth. MIT Press, Cambridge, pp 253–282

Buenstorf G (2003) Designing clunkers: demand-side innovation and the early history of the mountain bike”. In: Metcalfe S, Cantner U (eds) Change, transformation and development. Physica, Heidelberg, pp 53–70

Buenstorf G, Cordes C (2008) Can sustainable consumption be learned? a model of cultural evolution. Ecol Econ 67(4):646–657

Chai A (2007) Beyond the shadows of utility: evolutionary consumer theory and the rise of modern tourism. PhD thesis, Friedrich-Schiller-University, Jena

Chai A (2011) Consumer specialization and the Romantic transformation of the British Grand Tour of Europe. J Bioecon 13(3):181–203

Chai A, Moneta A (2010) Retrospectives: Engel curves. J Econ Perspect 24(1):225–240

Chai A, Moneta A (2012) “Back to Engel? some evidence for the hierarchy of needs,”. J Evol Econ 1–28

Charles K, Hurst E, Roussanov N (2009) Conspicuous consumption and race. Q J Econ 124(2):425–467

Christensen C (1997) The innovator’s dilemma. Harvard Business School Press, Harvard

Ciarli T, Lorentz A, Savona M, Valente M (2010) The effect of consumption and production structure on growth and distribution. a micro to macro model. Metroeconomica 61(1):180–218

Clements K, Chen D (1996) Fundamental similarities in consumer behavior. Appl Econ 28:747–757

Cordes C (2005) Long-term tendencies in technological creativity-a preference-based approach. J Evol Econ 15(2):149–168

Cordes C (2009) Changing your role models: social learning and the Engel curve. J Socio-Econ 38(6):957–965

Cunningham C (2008). You are what’s on your feet: men and the sneaker subculture. J Cult Retail Imag 1–6

Damasio A (2003) Looking for Spinoza: joy, sorrow, and the feeling brain. William Heinemann, London

De Vries J (2008) The industrious revolution: consumer behavior and the household economy, 1650 to the present. Cambridge University Press

Dietz T, Gardner GT, Gilligan J, Stern PC, Vandenbergh MP (2009) Household actions can provide a behavioral wedge to rapidly reduce US carbon emissions. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106:18452–18456.

Dopfer K, Foster J, Potts J (2004) Micro-meso-macro. J Evol Econ 14(3):263–279

Dosi G (1982) Technological paradigms and technological trajectories: a suggested interpretation of the determinants and directions of technical change. Res Policy 12:147–162

Dulleck U, Kerschbamer R (2006) On doctors, mechanics, and computer specialists: the economics of credence goods”. J Econ Lit 44:5–42

Earl P (1986) Lifestyle economics: consumer behaviour in a turbulent world. Wheatsheaf Books, Sussex

Earl P (1998) Consumer goals as journeys into the unknown. In: Bianchi M (ed) The active consumer: novelty and surprise in consumer choice. Routledge, London, pp 122–140

Earl P, Potts J (2004) The market for preferences. Camb J Econ 28:619–633

Flinn M (1997) Culture and the evolution of social learning. Evol Hum Behav 18:23–67

Foxall GR, Oliveira-Castro JM, Schrezenmaier TC (2004) The behavioral economics of consumer brand choice: patterns of reinforcement and utility maximization. Behav Process 66(3):235–260

Frank R (1985) The demand for unobservable and other nonpositional goods. Am Econ Rev 75(1):101–116

Frenzel Baudisch A (2006) Continuous market growth beyond functional satiation: time-series analyses of US footwear consumption, 1955–2002 (No. 0603). Papers on economics and evolution

Gallouj F, Weinstein O (1997) Innovation in services. Res Policy 26(4):537–556

Gifford R, Kormos C, McIntyre A (2011) Behavioral dimensions of climate change: drivers, responses, barriers, and interventions. Climate Change 2:801–827

Gigerenzer G, Todd PM, ABC Research Group (1999) Simple heuristics that make us smart. Oxford University Press, New York

Guerzoni M (2010) The impact of market size and users’ sophistication on innovation: the patterns of demand. Econ Innov New Technol 19(1):113–126

Hayek FA (1960) The constitution of liberty. Routledge, London

Hergenhahn B, Olson M (1997) An introduction to theories of learning. Prentice Hall, New Jersey

Herrendorf B, Rogerson R, Valentinyi Á et al. (2013) Growth and structural transformation (No. w18996). National Bureau of Economic Research

Hipp C, Grupp H (2005) Innovation in the service sector: the demand for service-specific innovation measurement concepts and typologies. Res Policy 34(4):517–535

Hippel E (2005) Democratizing innovation. MIT Press, London

Hopkins E, Kornienko T (2004) Running to keep in the same place: consumer choice as a game of status. Am Econ Rev 94(4):1085–1107

Houthakker HS (1992) Are there laws of consumption? in aggregation, consumption and trade. Springer, Netherlands, pp 219–223

Jonsson PO (1994) Social influence and individual preferences: on schumpeter’s theory of consumer choice”. Rev Soc Econ 52(4):301–314

Kahneman D (2003) Maps of bounded rationality: psychology for behavioral economics. Am Econ Rev 93(5):1449–1475

Kaus W (2013a) Conspicuous consumption and ‘race’: evidence from South Africa. J Dev Econ 100(1):63–73

Kaus W (2013b) Beyond Engel’s law-a cross-country analysis. J Socio-Econ 47:118–134

Keynes JM (1933) Economic possibilities for our grandchildren (1930). essays in persuasion 358–73

Kindleberger C (1989) Economic laws and economic history. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Lades LK (2013) Explaining shapes of Engel curves: the impact of differential satiation dynamics on consumer behavior. J Evol Econ 23(5):1023–1045

Lades LK (2014) Impulsive consumption and reflexive thought: nudging ethical consumer behavior. J Econ Psychol 41:114–128

Laibson D (2001) A cue-theory of consumption. Quarter J Econ 81–119

Lancaster K (1971) Consumer demand: a new approach. Columbia University Press, New York

Langlois R (2001) Knowledge, consumption and endogenous growth. In: Witt U (ed) Escaping satiation. Springer, Berlin

Langlois R, Cosgel M (1998) The organization of consumption. In: Bianchi M (ed) The active consumer. Routledge, London, pp 107–121

Lebergott S (1993) Pursing happiness- American consumers in the twentieth century. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Lewbel A (2008) “Engel curves,” in new Palgrave dictionary of economics, 2nd edn. Palgrave, Macmillan

Lipsey RG, Carlaw KI, Bekar CT (2005) Economic transformations: general purpose technologies and long-term economic growth: general purpose technologies and long-term economic growth. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Loasby B (1999) Knowledge, institutions and evolution in economics. Routledge, London

Malerba F, Nelson R, Orsenigo L, Winter S (2007) Demand, innovation, and the dynamics of market structure: the role of experimental users and diverse preferences. J Evol Econ 17(4):371–399

Manig C (2010) Is it ever enough? food consumption, satiation and obesity (No. 1014). Papers on economics and evolution

Manig C, Moneta A (2009) More or better? measuring quality versus quantity in food consumption (No. 0913). Papers on economics and evolution

Maréchal K (2010) Not irrational but habitual: the importance of “behavioral lock-in” in energy consumption”. Ecol Econ 68:1104–1114

Markides C (2006) Disruptive innovation: in need of better theory. J Prod Innov Manag 23:19–25. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5885.2005.00177.x

Maslow AH (1943) A theory of human motivation. Psychol Rev 50(4):370

Max-Neef M (1991) Human-scale development- conception, application and further reflection. Apex Press, London

McCloskey D, Klamer A (1995) One quarter of GDP is persuasion. Am Econ Rev 191–195

McFarland D (1987) The oxford companion to animal behavior. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Menger C (1871) Principles of economics. The Free Press, Glencoe

Metcalfe S, Foster J, Ramlogan R (2006) Adaptive economic growth. Camb J Econ 30:7–32

Mokyr J (2000) Why ‘more work for mother?’ knowledge and household behavior, 1870–1945”. J Econ Hist 60:1–41

Mokyr J (2002) Gifts of Athena. Princeton University Press, Princeton and Oxford

Moneta A, Chai A (2014) The evolution of Engel curves and its implications for structural change theory. Camb J Econ 38(4):895–923

Nelson RR, Consoli D (2010) An evolutionary theory of household consumption behavior. J Evol Econ 20(5):665–687

Nelson RR, Winter SG (1982) An evolutionary theory of economic change. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Nisbet MC, Myers T (2007) The polls—trends 20 years of public opinion about global warming. Public Opin Quarter 71(3):444–470

Norton B, Costanza R, Bishop RC (1998) The evolution of preferences: whysovereign’preferences may not lead to sustainable policies and what to do about it. Ecol Econ 24(2):193–211

O’Hara SU, Stagl S (2002) Endogenous preferences and sustainable development. J Socio-Econ 31(5):511–527

Parker PM, Tavassoli N (2000) Homeostasis and consumer behavior across cultures. Int J Res Mark 17:33–53.

Pasinetti LL (1981) Structural change and economic growth. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Pecchi L, Piga G (2008). Revisiting Keynes: economic possibilities for our grandchildren. MIT Press

Potts J (2001) Knowledge and markets. J Evol Econ 11:413–431

Rolls ET (2005) Emotion explained (vol. 22). Oxford University Press, Oxford

Røpke I (1999) The dynamics of willingness to consume. Ecol Econ 28:399–420

Røpke I (2009) Theories of practice—new inspiration for ecological economic studies on consumption. Ecol Econ 68:2490–2497

Ruprecht W (2002) Preferences and novelty: a multidisciplinary perspective. In: McMeekin A, Green K, Tomlinson M, Walsh V (eds) Innovation by demand. Manchester University Press, Manchester, pp 56–74

Ruprecht W (2005) The historical development of the consumption of sweeteners-a learning approach. J Evol Econ 15(3):247–272

Sanne C (2002) Willing consumers or locked-in? policies for a sustainable consumption. Ecol Econ 42:273–287

Sartorius C (2003) An evolutionary approach to social welfare. Routledge, New York

Saviotti P (1996) Technological evolution, variety and the economy. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Saviotti PP, Pyka A (2008) Micro and macro dynamics: industry life cycles, inter-sector coordination and aggregate growth. J Evol Econ 18(2):167–182

Schubert C (2012) Is novelty always a good thing? towards an evolutionary welfare economics. J Evol Econ 22(3):585–619

Scitovsky T (1976) The joyless economy: an inquiry into human satisfaction and consumer dissatisfaction. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Stigler G, Becker G (1977) De gustibus non est disputandum. Am Econ Rev 67:76–90

Stiglitz JE (2008) Toward a general theory of consumerism: reflections on Keynes’s economic possibilities for our grandchildren. Pecchi L, Piga G (red.), Revisiting Keynes: economic possibilities for our grandchildren, 41–86

Stuart EW, Shimp TA, Engle RW et al. (1987) Classical conditioning of consumer attitudes: four experiments in an advertising context. J Consumer Res 334–349

Swann GM (2002) There’s more to economics of consumption than (almost) unconstrained utility maximization. In: McMeekin A, Green K, Tomlinson M, Walsh V (eds) Innovation by demand. Manchester University Press, Manchester, pp 23–40, +

Swedberg R (1994) Markets as social structures. In: Smelser N, Swedberg R (eds) The handbook of economic sociology. Princeton University Press, Princeton, pp 313–341

Thiele S, Weiss C (2003) Consumer demand for food diversity: evidence for Germany. Food Policy 28(2):99–115

Valente M (2012) Evolutionary demand: a model for boundedly rational consumers. J Evol Econ 22(5):1029–1080

Volland B (2012) The history of an inferior good: beer consumption in Germany (No. 1219). Papers on economics and evolution

Volland B (2013) On the intergenerational transmission of preferences. J Bioecon 15(3):217–249

Walton J (2000) The British seaside: holidays and resorts in the twentieth century. Manchster University Press, Manchester

Windrum P (2005) Heterogeneous preferences and new innovation cycles in mature industries: the amateur camera industry 1955–1974”. Ind Corp Chang 14:1043–1074

Witt U (2001) Learning To Consume—a theory of wants and the growth of demand. J Evol Econ 11:23–36

Witt U (2011) The dynamics of consumer behavior and the transition to sustainable consumption patterns. Environ Innov Soc Transit 1(1):109–114

Witt U (2016) The evolution of consumption and its welfare effects. J Evol Econ (this issue)

Witt U, Wörsdorfer JS (2011) Parting with“ blue monday”: preferences in home production and consumer responses to innovations (no. 1110). Papers on economics and evolution

Woersdorfer JS (2010) Consumer needs and their satiation properties as drivers of the rebound effect: the case of energy-efficient washing machines (No. 1016). Papers on economics and evolution

Woersdorfer JS (2010b) When do social norms replace status-seeking consumption? an application to the consumption of cleanliness. Metroeconomica 61(1):35–67

Woersdorfer JS, Kaus W (2011) Will nonowners follow pioneer consumers in the adoption of solar thermal systems? empirical evidence for northwestern Germany. Ecol Econ 70(12):2282–2291

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank John Foster, Wolfhard Kaus, Alessio Moneta, Ulrich Witt, Leo Lades and the two anonymous referees for their comments. This work also benefit from ongoing discussions with Alex Frenzel Baudisch, Corinna Manig, Julia Sophie Wörsdorfer, Stefan Bruns, Ben Volland, Thomas Brenner, Christian Cordes, Jason Potts, Wilhelm Ruprecht, Christian Schubert, Guido Bünstorf, Martin Binder, Tom Broekel, John Foster and Stan Metcalfe. An earlier version of this papers was presented at the 15th International Schumpeter Society in Jena, Germany, 2014. The author thanks the participants for their comments. This research was supported by the Griffith Business School. The usual disclaimer applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Part of this Research was financially funded by Griffith University (Australia).

This research did not involve any research on human or animal subjects.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chai, A. Tackling Keynes’ question: a look back on 15 years of Learning To Consume. J Evol Econ 27, 251–271 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-016-0455-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-016-0455-7