Abstract

The notion of organizational commitment has been intensively discussed in many fields of contemporary management research. Current literature in the field of leadership suggests that leadership styles of top management, i.e., CEOs and business unit heads, affect the level of commitment among middle- and lower-level managers. In a parallel vein, scholars in the field of management accounting and control argue that these effects are due to an organization’s management control system. This study is aimed at closing the gap between both strands of literature and examines how leadership and management control systems interact in the process of creating organizational commitment. Building on structural equation modeling, the study extends existing knowledge by analyzing whether the relations between top management’s leadership styles, i.e., initiating structure and consideration, and organizational commitment are mediated by the use of formal and informal management control elements. Based on a sample of 294 German firms, the results suggest that informal control elements, such as personnel and cultural controls, act as hinges through which top management is able to positively transmit leadership behaviors and affect the development of organizational commitment.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The notion of organizational commitment has been of major importance in many fields of contemporary management research. The continuing interest in organizational commitment primarily stems from its favorable effects on performance and other facets of work-related behavior, such as absenteeism, turnover, and motivation (Meyer et al. 2002; Gregson 1992; Mathieu and Zajac 1990). Moreover, a large number of theoretical and empirical works have acknowledged its positive effects on organizational citizenship behaviors, such as extra-role behaviors and the use of private information in favor of the organization (Chong and Eggleton 2007). Consequently, management literature has made great efforts to determine the various antecedents to organizational commitment (Chen and Indartono 2011). In particular, empirical findings suggest that personal as well as organizational characteristics are able to determine the level of joint commitment among the members of a workforce.

With respect to personal characteristics, a large body of literature is concerned with the interrelations between leaders and the workgroup, and especially how leadership styles of top executives (e.g., CEOs or business unit heads) are related to the level of organizational commitment (Fu et al. 2010; Dale and Fox 2008; Brown and Trevino 2006; Meyer et al. 2002; Podsakoff et al. 1996; Mathieu and Zajac 1990; Morris and Sherman 1981). It is generally argued that the behaviors of those top executives determine the way in which they establish direction, align people, and motivate as well as inspire organizational members (Kotter 1990; Jago 1982; Selznick 1957). The fulfillment of these sub-processes of leadership is subsequently expected to be related to an increased level of organizational commitment. In other words, the expression of appropriate leader behaviors is considered an important element in fostering a high-commitment environment and thus effective leadership (Caldwell et al. 2011).

In reference to organizational characteristics, literature in the area of management accounting and control suggests that an organization’s management control system (MCS) is an important variable in explaining organizational commitment. In line with this argument, the use of different control elements is geared towards addressing organizational control problems, such as lack of direction or motivational problems (Merchant and Van der Stede 2012; DeCotiis and Summers 1987). In order to close the gap between ‘what is desired’ and ‘what is likely’, management benefits from an optimal control system use by ensuring the adequate level of commitment necessary to mitigate adverse effects resulting from motivational and directional problems (Abernethy and Chua 1996).

Although it has been widely recognized that leadership and management control are related, advancements of knowledge have often been made in isolation from each other, leaving the various links between both disciplines largely unexplored (Davila and Foster 2007; Otley and Pierce 1995). Existing empirical evidence suggests that the use of an organization’s management control system (e.g., the use of specific performance measures, the delegation of decision rights, or the use of planning systems) is to some extent dependent on individual differences in top executives’ personal characteristics, such as their leadership styles (e.g., Jansen 2011; Abernethy et al. 2010; Hartmann et al. 2010). Nevertheless, this research neither explicitly accounts for organizational commitment as a dependent variable nor addresses the use of informal controls as an integral part of the overall control environment.

To extend the body of literature on leadership and management control, we specifically address these two gaps by taking up a research question which focuses on whether and how the elements of an organization’s management control system act as hinges to express leadership styles of top executives (i.e., CEOs and business unit heads) and subsequently explain their leadership impact on the level of joint commitment among middle- and lower-level managers. In this setting, the total effects of leadership styles on organizational commitment consist of the sum of the direct as well as the indirect or mediating effects attributed to the use of different management control elements. In response to the discussion about a broader conceptualization of management control systems (e.g., Berry et al. 2009; Malmi and Brown 2008; Sandelin 2008; Chenhall 2003; Fisher 1998, 1995; Dent 1990; Flamholtz et al. 1985; Otley 1980), we place a special emphasis on the inclusion of informal management control elements, such as personnel and cultural controls. We therefore acknowledge that organizational control is not only exercised through the use of results-based mechanisms (Hopwood 2009), but also contains elements that work more implicitly. As corresponding literature suggests that informal elements constitute important variables in explaining behavioral responses to the organization’s overall control environment, a broader approach, which seeks to encompass both formal and informal control elements, is thus expected to facilitate our understanding about the emergence of organizational commitment (Ouchi 1979).

Based on survey data from 294 medium- and large-sized German firms, our study contributes to the existing body of knowledge in the following ways. First, our results show that the direct effects of top executives’ leadership styles on organizational commitment are relatively weak. Instead, the total effect rather stems from different management control elements that act as a crucial hinges between leadership styles and organizational commitment. Second, our findings suggest that especially personnel and cultural controls can be observed as critical and positive mediators that translate leadership styles into organizational commitment. Third, taking both direct and indirect effects into account, our results recommend that top executives may have a greater impact on organizational commitment by focusing on considerate leadership behaviors.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. In the subsequent section, we discuss the relevant literature on the aspects of organizational commitment, management control, and leadership. Section 3 encompasses the development of hypotheses that seek to explain how leadership styles affect organizational commitment directly as well as indirectly through the use of formal and informal control elements. In Sects. 4 and 5, we give an overview on the methodological approach and present the empirical results. In Sect. 6, we provide a discussion of the main findings and address the limitations of our analysis as well as several implications for further research.

2 Literature review

Organizational commitment has been subject to many efforts in both theoretical and empirical research in the field of management. Research primarily focuses on organizational commitment as the “relative strength of an individual’s identification with and involvement in an organization” (Porter et al. 1974, p. 604). Building on this definition, related literature usually emphasizes three important dimensions of organizational commitment: (1) a strong belief in the organization’s goals and values, (2) the willingness to spend considerable effort on behalf of the organization, and (3) the intent to be a valued member of the organization. Individuals with high levels of commitment therefore show not only a passive affiliation to the organization based on their thoughts, beliefs, or feelings, but also take on an active role in contributing to the goals and the overall welfare of the organization (Jaworski and Young 1992; Mowday et al. 1979). Moreover, managers who are highly committed are more likely to engage in actions in favor of the organization, rather than acting in pursuit of their pure self-interest (Chong and Eggleton 2007). Lastly, empirical studies in behavioral literature provide evidence that goes far beyond the favorable effects on organizational excellence and implicates that even society as a whole can benefit from increased organizational commitment (Mathieu and Zajac 1990).

Today, it is generally acknowledged that the level of organizational commitment is dependent on the leadership characteristics of an organization’s key personnel. Recent definitions characterize leadership as the process by which top managers intentionally exert influence over “other people to guide, structure, and facilitate activities and relationships in a group or organization” (Yukl 2013, p. 18). Literature suggests further that a top manager’s influence manifests itself in the establishment of direction, the alignment of personnel, as well as the motivation and inspiration of people (Kotter 1990). The behavioral style used to exert this influence is subsequently referred to as the leadership style of that manager.

Research on leadership styles usually follows one of the major paradigms that classify leader behaviors into different categories (DeRue et al. 2011). Prior studies in management accounting primarily draw on the conceptualization provided by the Ohio Leader Behavior Description Questionnaire (LBDQ) which captures leader behavior using the dimensions of initiating structure and consideration (Fleishman 1957; Halpin and Winer 1957). Behaviors of initiating structure represent a clear definition of the leader’s own role and that of his or her subordinates towards goal attainment and contain elements of both task-orientation as well as directiveness. The consideration dimension contains elements of participative decision making as well as an emphasis on friendly, trusting, and respectful relationships in order to achieve the desired outcomes (Bass 2008; Otley and Pierce 1995; Kida 1984; Jiambalvo and Pratt 1982; Hopwood 1974; Schriesheim and Kerr 1974). The LBDQ dichotomy receives its popularity due to a number of reasons. First, it has been used in several studies in the field of management accounting, underlining its usefulness for addressing our research objective as well the comparability of our results to previous and future findings (Abernethy et al. 2010; Hartmann et al. 2010; Otley and Pierce 1995; Brownell 1983). Second, the measurement instruments show sufficient values for reliability and validity which have been confirmed several times (Jugde et al. 2004; Seltzer and Bass 1990; Jiambalvo and Pratt 1982; Bass 1981). Similarly, they have been found to be stable and robust against situational factors (Bass 2008). In addition, given the validity of the measurement instruments, Jugde et al. (2004) suggest further research with respect to initiating structure and consideration.

In a parallel vein, organizational commitment is influenced by the use of an organization’s management control system. Extant literature contains a substantial number of definitions and classifications of management control systems which primarily follow an instrumental or tool-based approach to align individual interests with corporate objectives and strategies (Morsing and Oswald 2009). Early conceptualizations, such as the seminal work of Anthony (1965), define management control systems as a cybernetic process through which higher-level managers measure the achieved levels of their subordinates’ performance, compare these levels to a pre-defined target, and take, if necessary, corrective action (Green et al. 1988). Newer and much broader conceptualizations (e.g., Merchant and Van der Stede 2012), however, characterize management control systems as “all the devices or systems managers use to ensure that the behaviors and decisions of their employees are consistent with the organization’s objectives and strategies” (p. 6). This more comprehensive perspective takes into account that effective management control is not limited to the use of feed-back loops of financial performance, but also expressed through a combination of different control elements (Malmi and Brown 2008; Widener 2007; Bisbe and Otley 2004; Abernethy and Chua 1996; Macintosh and Daft 1987; Merchant 1985; Otley 1980; Ouchi 1979, 1977).

Recent textbook analyses among accounting researchers (Strauß and Zecher 2013) stress the usefulness of the object-of-control framework (Merchant and Van der Stede 2012; Merchant 1985) as a means to capture the variety of potential control alternatives. The application of this framework explicitly allows for the simultaneous analysis of formal and informal management control elements by differentiating between results, action, personnel, and cultural controls. Results and action controls, on the one hand, typically reside within the domain of formal control elements as they are concerned with either an ex post measurement of the financial and non-financial outcomes of managerial behavior (Widener 2004; Hansen et al. 2003; Snell 1992) or a direct observation of managerial activities. Results controls contain formal instruments based on financial and non-financial key performance indicators, such as budgets, performance management systems, and transfer pricing schemes that help to “maintain financial viability and develop efficient and effective work processes” (Chenhall et al. 2010, p. 738). Action controls compare actual with desired behaviors by directly monitoring or supervising managerial activities (Dermer and Lucas 1986; Machin 1979) through sets of formal rules, standard operating procedures, pre-action reviews, and physical constraints (Cunningham 1992; Merchant 1985). Personnel and cultural controls, on the other hand, are more implicit instruments and can thus be denoted as being more informal in nature. Personnel controls mainly involve human resources activities, such as staff selection, trainings, and placement practices (Widener 2004; Abernethy and Brownell 1997). With the use of personnel measures, management aims at appropriately selecting and promoting the organization’s most powerful resource, i.e., their human capital. Cultural controls, on the other hand, work through processes of socialization and ensure that the organization’s values and assumptions are shared among its various members (Sandelin 2008; O’Clock and Devine 2003; Flamholtz et al. 1985).

Our analysis follows the many calls to connect both previously rather unrelated streams of research (Jansen 2011; Davila and Foster 2007; Otley and Pierce 1995). We thus address some of the missing links with respect to the various interdependencies of leadership styles and management control systems (Abernethy et al. 2010; Hartmann et al. 2010). More specifically, we aim at showing that leadership style is one of those top executive characteristics that affects both the use of specific management control elements as well as the overall commitment of its workforce.

3 Development of hypotheses

3.1 Initiating structure and consideration as antecedents to organizational commitment

It is commonly accepted that the level of joint commitment among middle- and lower-level managers of an organization is dependent on the leadership skills of its top managers, i.e., CEOs or business unit heads (DeRue et al. 2011; Dale and Fox 2008). In line with this argumentation, senior managers draw on specific sets of behaviors, i.e., leadership styles, which enable them to manage subordinates’ commitment according to personal and organizational demands.

Leader initiating structure refers to behaviors that are oriented towards detailed communication about expectations and procedures to follow. Top managers who stress the importance of structure therefore aim at providing a work environment that helps employees to better understand their role and what is expected of them in terms of overall goal achievement (Hartmann et al. 2010; Dale and Fox 2008). When expectations are clearer, employees’ beliefs in the dependability of the organization increase which in turn enhances their identification with and involvement in a particular organization (Morris and Steers 1980; Buchanan 1974). Clearer expectations also help lower-level managers to improve their personal work outcomes as goals are usually easier to understand (Luthans et al. 1987). If the ways towards goal attainment are transparent and goals are properly specified, these managers are more likely to expect their effort to be transformed into the achievement of organizational goals, in turn inducing a higher commitment towards the workplace (Wofford and Liska 1993; House and Mitchell 1974). Our hypothesis with respect to the direct effects of initiating structure on organizational commitment is therefore the following:

-

H1:

The direct effect of the initiating structure leadership style on organizational commitment is positive.

Leader consideration, on the other hand, refers to behaviors that focus on the social relationships between leaders and their workforce. Considerate leader behaviors thus address employees’ emotional needs as well as their involvement in social relationships (Dale and Fox 2008) and nurture those relationships by promoting a friendly, trusting, and respectful atmosphere in order to achieve the desired outcomes. As a result, the emergence of social ties motivates people to maintain membership in and work for the organization (Mowday et al. 1982). The positive impact of consideration on organizational commitment can also be attributed to the enhancement of interpersonal communication which reinforces employees’ control over work-related routines and outcomes (Hartmann et al. 2010). Hence, lower-level managers may express higher commitment through an increase in their efforts towards goal achievement. Our second hypothesis with respect to the direct effects of consideration on organizational commitment is therefore the following:

-

H2:

The direct effect of the consideration leadership style on organizational commitment is positive.

3.2 Formal and informal management control elements as mediating variables

The discussion about the impact of leadership styles on organizational commitment should, however, not be limited to its direct effects. Literature in the area of management accounting and control provides evidence that certain leader behaviors trigger the choice of specific management control practices (e.g., Abernethy et al. 2010; Hartmann et al. 2010; Kyj and Parker 2008) that are instrumental to the development of a high-commitment organization. The impact of leadership styles may therefore work also indirectly through the use of formal and informal management control elements which act as hinges to translate top managers’ preferences for structure and consideration into organizational commitment. In line with this argumentation, the following two sets of hypotheses investigate through which channels top managers control organizational commitment and whether the use of formal and informal management control elements helps or hinders their efforts in this matter.

Literature largely agrees that some of the tools available for senior managers to translate structuring behaviors into organizational commitment fall into the domain of formal control elements, i.e., results and action controls. Management literature recurrently advocates the use of those controls as a means to clarify expectations and provide detailed steps towards goal attainment (Waldman et al. 2001). Results controls are tools to objectively measure and compare individual performance levels against pre-set targets (Abernethy et al. 2010; Hopwood 1974). They are required as top management’s expectations are usually communicated via structured evaluation processes and performance-contingent rewards and are regarded as motivating for employees to increase the commitment towards their work and the organization as such (Merchant and Manzoni 1989). On the other hand, action controls transmit expectations and structure by defining the necessary work steps for routine tasks. The use of, e.g., formal policies and procedures manuals is intended to enable lower-level managers to shift their attention towards critical issues, resulting in higher productivity and goal achievement (Cardinal 2001). It is argued that the feeling of contributing to the welfare of an organization is a desirable work experience that is positively related to the emergence of commitment to this particular organization (Meyer and Allen 1987; Steers 1977).

At the same time, the use of formal systems is supposed to assist considerate leaders in managing their interpersonal relationships to subordinates. In terms of results controls, literature suggests that top managers keep in good standing with their subordinates by expressing appreciation through relying on, e.g., qualitative aspects of performance measurement (Noeverman and Koene 2000) or participative budgeting (Kyj and Parker 2008). Moreover, specific performance measures may be used as qualitative means to provide helpful feedback in case lower-level managers need concrete guidance towards their overall goal attainment (Hartmann et al. 2010). At the same time, it is frequently argued that interpersonal relations between top executives and their subordinates can be stimulated by the use of action controls. For example, providing lower-level managers with information on how to perform a certain activity and conducting pre-action reviews are regarded as tools to express a considerate leadership style (Noeverman and Koene 2000).

However, the use of formal control mechanisms may also build up extensive performance pressure or undermine people’s autonomy and self-control. In a long-term perspective, the sole use of formal controls may therefore be counterproductive in achieving leadership effectiveness. Literature advocates, e.g., that formal controls make lower-level managers comply with organizational objectives only temporarily, rather than enhancing the deeper-sited bonds that precede organizational commitment (Bouillon et al. 2006; Pfeffer 1998). In the worst case, an all-formal control setting may even lead to an alienation of employees from the organization (Ouchi 1979). In line with the latter, we suggest that the mere use of formal control elements interferes with the potential positive effects of initiating structure and consideration. We thus hypothesize that the indirect effects of both leadership styles on organizational commitment via the use of formal management control elements are negative.

-

H3a:

The indirect effect of the initiating-structure leadership style on organizational commitment via the use of formal management control elements is negative.

-

H3b:

The indirect effect of the consideration leadership style on organizational commitment via the use of formal management control elements is negative.

Alternatively, recent literature suggests that organizations are more effective when top management relies on a joint use of formal and informal approaches (Malmi and Brown 2008; Sandelin 2008; Widener 2007). In line with this argumentation, it is frequently suggested that top managers who express a structuring leadership style use an organization’s informal culture as an instrument to express their demands for timeliness, a well-organized flow of activities, as well as a focus on goal orientation (Otley and Pierce 1995). Moreover, they may rely more intensively on personnel controls in order to trim the selection and training of employees to respond well to the demands of a highly structured organization. By focusing on these mechanisms, top managers ensure that expectations are clear and roles and responsibilities are properly defined. The use of cultural and personnel controls can therefore be helpful in providing direction and motivating subordinates which positively affects organizational commitment.

When expressing a considerate leadership style, top managers may use cultural controls as a primary tool to communicate basic organizational values to their subordinates. When people know how to deal with specific situations and how to act according to the values of the organization, cooperation increases which in turn makes people willing to work for this particular organization. As corporate culture partly consists of unwritten rules and policies, senior managers have to engage in processes of mutual discussions and open communication to ensure its intended outcomes (Tucker 2010). These communication processes can be fostered by focusing on subordinates’ well-being as well as showing friendly and approachable behavior that strengthens the implicit relationships between upper- and lower-level management (Hopwood 1974). Additionally, top managers’ relationships with their subordinates can be linked to issues of attracting and managing the appropriate personnel. Considerate leaders may create a high-commitment environment not only by hiring the best-suited applicants for particular job positions, but also by selecting and educating employees to prevent potential misfits with organizational culture (Snell 1992; Ouchi 1979). By ensuring that organizational members tend to think and act alike, group cohesion increases which affects organizational commitment positively as well (Meyer and Allen 1987). As the use of informal management control elements therefore rather reinforces long-term organizational commitment, we hypothesize the following relationships:

-

H4a:

The indirect effect of the initiating-structure leadership style on organizational commitment via the use of informal management control elements is positive.

-

H4b:

The indirect effect of the consideration leadership style on organizational commitment via the use of informal management control elements is positive.

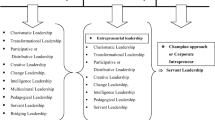

In a nutshell, our hypotheses suggest that, in addition to the direct effects of both leadership styles on organizational commitment, formal and informal management control elements work as intervening mechanisms between these variables. Whereas the use of formal control elements is expected to hinder the emergence of organizational commitment, the use of informal elements is considered to have positive effects. Based on our hypotheses, we establish the following research model (Fig. 1).

4 Method

4.1 Survey design, administration, and sample

Our study follows an empirical approach that analyzes the relationships between the level of joint commitment among middle- and lower-level managers, the leadership styles of CEOs or business units heads, and the control choices these managers undertake. Data was collected as part of a larger research project by means of an online survey from September to December 2011. Participants were chosen from a non-public database of 2,273 medium- to large-sized, cross-sectional German organizations. However, several firms were excluded due to double counts, the absence of an established management accounting department, or the general termination of business. In addition, financial institutions and real estate companies were excluded as this industry’s nature of business and regulatory requirements significantly differ from those of other industries.

We randomly distributed the questionnaire among the heads of management accounting departments of the remaining organizations. In line with recent research (e.g., Auzair and Langfield-Smith 2005), management accountants were selected due to their general understanding of the business processes and their expertise on an organization’s management control environment. Further, their regular contact with CEOs and business unit heads allows them to reliably assess leader behavior within their respective organization. Out of the 1,757 firms contacted, a total of 311 management accountants participated in the study (response rate: 17.70 %). However, a small number of questionnaires had to be discarded due to missing values or invalid responses. Firms with less than 50 employees (measured in headcount) were eliminated as our project specifically focuses on medium- and large-sized companies with a reasonable size to guarantee the existence as well as the frequent use of formal control elements. After all eliminations, our model is based on a final sample of 294 organizations. The descriptive statistics of the sample are provided in Table 1.

4.2 Variable measurement

The main variables are measured as latent constructs with multiple indicators (see Appendix for a detailed overview on the measurement instruments). To ensure the appropriateness of the measurement model, we particularly selected established instruments from previous studies which show appropriate values in terms of reliability and validity. In addition, pre-tests with academic scholars as well as business practitioners were used to ensure item clarity as well as the overall comprehensibility of the questionnaire.

In order to measure the extent to which the behaviors of CEOs or business unit heads are characterized by initiating structure and consideration, we rely on two scales provided by Hartmann et al. (2010) who in turn builds on items extracted from the Leader Behavior Description Questionnaire (LBDQ—Form XII) (Stogdill 1963). Jugde et al. (2004) recently confirm the validity of the construct by conducting an extensive meta-analysis of the different LBDQ forms. High values on each of the 13 items represent a strong manifestation of the respective leadership style.

The corresponding use of formal and informal management control elements is modeled on a second-order level which relates to results and action controls (formal control elements) as well as personnel and cultural controls (informal control elements) on the first-order level. We adopt this approach as a higher-order structure typically supports a greater theoretical parsimony, is able to reduce model complexity (Becker et al. 2012; Wetzels et al. 2009), and allows for the interpretation of the results in a more general way (Law et al. 1998). Our variable measurement further takes into account that management control elements must be observed distinctly from the general leadership style of the respective manager (Abernethy et al. 2010; Hartmann et al. 2010). The use of results controls is measured by a five-item scale originally developed by Jaworski and MacInnis (1989) to measure ‘output control’ as well as an adapted version of this construct which assesses the reliance of individual goals and their linkage with the overall incentive system (Hutzschenreuter 2009). The measurement of action controls builds on four items of the ‘behavior control’ construct developed by Jaworski and MacInnis (1989) as well as a refinement of this construct (Hutzschenreuter 2009). An additional item is drawn from Kren and Kerr (1993) to capture the reliance on policies and procedures manuals. Personnel controls are measured by four adapted items used by Hutzschenreuter (2009) who in turn relies on Snell’s (1992) instrument to capture ‘input control’. In addition to these measures, we use one item from Wargitsch (2010) to assess the process of employee selection more precisely. The use of cultural controls is measured by one item developed by Wargitsch (2010) who builds on Ouchi’s (1979) instrument to assess the existence of ‘clan control’. We also add to our measurement four items from the ‘beliefs system’ construct used by Widener (2007). High values on each of the items measuring management controls represent a strong presence of the respective control form.

The measurement of organizational commitment is based on a five-item instrument provided by Johnson et al. (2002) which essentially constitutes an adapted version of the original instrument developed by Mowday et al. (1979). High values on each of the items indicate a high level of joint commitment of an organization’s middle- and lower-level management from an organizational-level perspective.

To ensure the robustness of our findings, we assess the impact of several control variables. Previous studies show that organizational variables are associated with environmental uncertainty (e.g., Hartmann et al. 2010; Chenhall 2003; Merchant 1990; Govindarajan 1984). We measure this variable based on three items drawn from Hartmann et al. (2010) which capture the extent to which external factors, such as behaviors of customers, competitors, or suppliers, have an influence on the use of specific management control elements as well as organizational commitment. In addition, management accounting literature frequently stresses the effects of organizational size on the formality of the overall control system or the choice of specific management control elements, e.g., budgets (Chenhall 2003). In line with this argumentation, we calculate the natural logarithm of the number of employees on average employed by the organization (measured in headcount) during its last business year (Libby and Waterhouse 1996; Snell 1992). The choice of specific control elements and the level of organizational commitment might also be dependent on whether founding families have a significant proportion of ownership and express a significant commitment towards the business’s well-being. We therefore assess whether the organization is a family firm according to the founding family definition (Achleitner et al. 2009; Villalonga and Amit 2009; Anderson and Reeb 2003). Due to regulatory requirements necessary for the purpose of stock market listing, listed organizations might rather employ formal systems compared to non-listed firms. Accordingly, we assessed whether a listing on any potential international stock market is applicable.

4.3 Data analysis

Data analysis relies on partial least squares (PLS), a variance-based approach of structural equation modeling (SEM) used to simultaneously analyze and test multiple construct relationships, i.e., causal links between latent variables (Hair et al. 2012b; Chin and Newsted 1999). PLS is a non-parametric approach that is especially powerful when the available data is non-normal (Hair et al. 2012a; Ringle et al. 2012) and the model to be tested is characterized by (1) a larger number of latent variables with multiple indicators (Hair et al. 2012b; Chin and Newsted 1999), (2) the use of higher-order constructs (Becker et al. 2012; Wetzels et al. 2009), and (3) multiple mediating effects (Ringle et al. 2012; Iacobucci 2010). In addition, PLS is mainly used in causal-predictive research contexts that are mainly explorative in nature, i.e., it is applied when theoretical and empirical knowledge about causal relationships between the constructs is rather fluid (Hartmann et al. 2010). A recent review of PLS-related publications in the field of management accounting (Lee et al. 2011) finally supports our notion that this approach is appropriate for research questions in this field (e.g., Abernethy et al. 2010; Hartmann et al. 2010).

5 Results

5.1 Measurement model

The measurement model is assessed in terms of indicator reliability, internal consistency reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity (Hair et al. 2012b, 2011; Henseler et al. 2009).

Indicator reliability is considered satisfactory as all standardized factor loadings exceed the required threshold of 0.7 (Hair et al. 2011). However, three items fall slightly below this threshold but are still well above 0.6 which is why we decided to include them in our model.

Internal consistency of the constructs is assessed using Cronbach’s alpha (CA) and composite reliability (CR). Critical values are 0.5 or 0.6 for CA and 0.7 for CR (Henseler et al. 2009). As provided in Table 1, all latent variables show high values for Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability, indicating high internal consistency. A notable exception is environmental uncertainty. However, we regard our measurement to be satisfactory as Cronbach’s alpha rather underestimates internal consistency (Henseler et al. 2009) and composite reliability, which tends to be more suitable in a PLS context (Hair et al. 2011), shows a sufficiently high value.

Convergent validity of the constructs can be determined using the average variance extracted (AVE) (Fornell and Larcker 1981). Generally, our results are sufficient as none of the AVEs fall below the critical threshold of 0.5 (Henseler et al. 2009).

Finally, discriminant validity exists at the construct level if the square root of the AVE of a latent variable is higher than the correlations of this variable with all other latent variables (Hair et al. 2011; Fornell and Larcker 1981). As shown in Table 2, this is supported as the diagonal elements are higher than the off-diagonal elements. Discriminant validity at the item level is assessed through an evaluation of the cross loadings. Table 3 shows that the indicators load highest on the factor they intend to measure.

5.2 Structural model

The appropriateness of the structural model is assessed in terms of an evaluation of the coefficients (\(\beta )\) and significance levels (t values) of the structural paths. In addition, we calculate the explained variances of the endogenous constructs (R\(^{2})\), the effect sizes (f\(^{2})\) for each of the main paths, as well as cross-validated redundancy (Q\(^{2})\) measures for the endogenous variables (Henseler et al. 2009). T values and standard errors needed for the evaluation of the statistical significance of the paths are obtained by means of bootstrapping with 1,000 runs with replacement. The results of the structural model are summarized in Table 4. A graphical illustration of the main model is presented in Fig. 2.

PLS results of the structural model. N = 294; PLS structural model with path coefficients (t values in parentheses). Paths from control variables to the dependent variables are not shown in the structural model. Control variables: environmental uncertainty (EUNC), size (SIZE), family firm status (FAM), stock market listing (LIST). Significance levels (two-tailed bootstrap confidence intervals; 1,000 runs): *** p \(<\) 0.01 (2.581). Measurement based on answers from management accountants

Hypotheses H1 and H2 suggest positive direct effects of both leadership styles on organizational commitment. Our empirical results do not support the hypothesized direct effect of initiating structure on organizational commitment (H1: \(\beta \) \(=\) 0.033, t \(=\) 0.844, p \(>\) 0.10). The consideration dimension, however, shows a direct and positive effect on organizational commitment (H2: \(\beta \) \(=\) 0.202, t \(=\) 3.007, p \(<\) 0.01).

Hypotheses H3a and H3b investigate whether the use of formal control elements mediates the effects of both leadership styles on organizational commitment. Our hypotheses suggest that the indirect effects of both leadership styles via the use of formal management control elements are negative. We find that both initiating structure and consideration affect the use of formal control elements positively (LSIS: \(\beta \) \(=\) 0.292, t \(=\) 4.531, p \(<\) 0.01; LSC: \(\beta \) \(=\) 0.193, t \(=\) 3.283, p \(<\) 0.01). Contrary to our expectations, the use of formal control elements is not significantly related to organizational commitment (\(\beta \) \(=\) \(-\)0.082, t \(=\) 1.453, p \(>\) 0.10). Therefore, H3a and H3b cannot be supported.

With respect to hypotheses H4a and H4b, we expect that the use of informal control elements mediates the effects of both leadership styles on organizational commitment and that the signs of the indirect effects are positive. Our results confirm our expectation as initiating structure and consideration show positive effects on the use of informal control elements (LSIS: \(\beta \) \(=\) 0.330, t \(=\) 6.358, p \(<\) 0.01; LSC: \(\beta \) \(=\) 0.375, t \(=\) 7.274, p \(<\) 0.01), which in turn is positively related to organizational commitment (\(\beta \) \(=\) 0.516, t \(=\) 8.215, p \(<\) 0.01). Using Sobel’s (1982) z-test, we find that the effects of both leadership styles on organizational commitment are partially mediated through the use of informal control elements (LSIS: z \(=\) 5.023, p \(<\) 0.01; LSC: z \(=\) 5.377, p \(<\) 0.01).

The existence of multiple mediated relationships allows the calculation of the total effects of both leadership styles on organizational commitment (Albers 2010). These effects consist of the sum of the direct effects as well as the indirect effects resulting from the link between leadership styles and formal and informal management control elements. The total effects of both leadership styles on organizational commitment can therefore be calculated as 0.179 (t \(=\) 2.775, p \(<\) 0.01) for initiating structure and 0.380 (t \(=\) 6.408, p \(<\) 0.01) for consideration. We further analyze the strengths of the mediating effects by calculating the proportion of the total effects due to the use of informal control elements (Shrout and Bolger 2002). Our results indicate that the use of informal management controls mediates the effect of consideration on organizational commitment only moderately (51 %). The effect of initiating structure on organizational commitment, however, is almost perfectly mediated by the use of informal controls (95 %).

The explanatory power of our model is adequate and comparable to other studies in the field (e.g., Abernethy et al. 2010; Hartmann et al. 2010). Values for multiple squared correlations (R\(^{2})\) suggest that leadership styles explain 25.5 % of the variance of formal management controls and 36.8 % of the variance of informal management controls. Leadership styles as well as formal and informal management controls are subsequently able to explain 42.3 % of the variance of organizational commitment.

We further calculate effect sizes (f\(^{2}\)) (Cohen 1988) for each direct path in our structural model (Table 4). The inclusion of effect sizes as a means to measure the increase in R\(^{2}\) in a dependent variable relative to its unexplained variance is particularly suited to determine how the R\(^{2}\) value of a dependent variable is affected by a particular independent variable (Lee et al. 2011; Henseler et al. 2009).

In addition, we use the predictive sample reuse technique (Geisser 1974; Stone 1974) to assess the predictive relevance (cross-validated redundancy Q\(^{2})\) of the independent variables. Q\(^{2}\) is calculated by using a blindfolding procedure in which parts of the original data set are omitted and reconstructed by the estimated parameters (Hair et al. 2011). Our model shows sufficient predictive relevance as Q\(^{2}\) values are well above the required threshold of zero (f_MCS: 0.118; i_MCS: 0.195; OCOMM: 0.296) (Chin 1998).

In terms of non-hypothesized effects, the impact of control variables on the use of formal and informal control elements as well as organizational commitment is largely insignificant. However, size is positively correlated with the use of formal management control elements (\(\beta \) \(=\) 0.139, t \(=\) 2.742, p \(<\) 0.01). In addition, family firm status is negatively correlated with the use of formal control elements (\(\beta \) \(= -0.115\), t \(=\) 2.211, p \(<\) 0.05).

6 Discussion and conclusion

Extant management literature contains a rich body of research indicating that a leader’s style of behavior is closely linked to the commitment of an organization’s middle- and lower-level management. At the same time, scholars in the field of management accounting and control argue that management control systems serve as important tools in creating commitment towards the achievement of organizational goals. Despite potential overlaps between both strands of research, advancements of knowledge are often made in isolation from each other. The objective of our paper is to connect both streams of research by providing a model that accounts for the effects of formal and informal management control elements which serve as hinges between leadership styles and organizational commitment.

Our study contributes to recent literature in the following ways. First, we show that the direct effects of leadership styles of initiating structure and consideration on organizational commitment are rather weak. Instead, the positive effects of both styles are largely due to the concurrent use of management control systems as indispensable tools to translate leadership behavior into organizational commitment. We therefore provide evidence that the frequent assertion that leadership styles precede organizational commitment (e.g., Meyer et al. 2002; Mathieu and Zajac 1990) has to be analyzed in greater detail and that future research should focus on the indirect links or potential mediating effects more closely (cf. Dale and Fox 2008).

Second, we find a strong connection between the type of management control instrument used and the level of organizational commitment. Whereas prior research has profoundly elaborated on the various outcomes of performance measurement systems or formal systems in general, recent studies advocate a more comprehensive view of management control systems (Malmi and Brown 2008; Sandelin 2008). The adoption of this perspective takes into account that organizational control works to some extent implicitly and apart from purely results-based mechanisms. We suggest that a more comprehensive perspective is of major importance in the discussion about antecedents and outcomes of management control systems (Luft and Shields 2003) as different modes of control affect organizational commitment in different ways. Although we find that both structuring and considerate leaders use formal controls for purposes of directing and motivating employees, the use of these elements does not mediate the relationships between leadership styles and organizational commitment. Instead, we provide evidence that the positive effects of top management leadership styles on organizational commitment are mediated by the use of informal systems. Our results are therefore in line with previous research that questions the universal assumption that formal control systems lead to more positive organizational outcomes (e.g., Marginson 1999; Snell and Youndt 1995). In addition, our findings support the notion that research on informal control elements is particularly worthwhile (Chenhall et al. 2011, 2010) as these mechanisms trigger positive behavioral responses to an organization’s control environment (Widener 2007).

Third, we find that top executives use informal control elements regardless of their leadership style as both initiating structure and consideration can be transmitted via the use of personnel and cultural controls. However, a nearly perfect mediation of the effect of initiating structure on commitment suggests that the use of these elements is especially important when top executives express these behaviors. Although also considerate behaviors can be transmitted by the use of informal control elements, our results indicate a small and significant direct effect of consideration on organizational commitment. We are therefore positive that considerate behaviors are also transmitted through some mechanism other than management controls. Clarifying the means by which this happens should be on the agenda for further research.

Fourth, our results support positive effects of structuring and considerate leader behaviors on organizational commitment. We therefore agree with previous work in stating that organizational members value the existence of clear expectations and procedures to follow as well as the presence of a friendly, trusting, and respectful work atmosphere (e.g., Mathieu and Zajac 1990). However, as a leader’s considerate style shows a stronger influence on organizational commitment, we advise top executives who strive for the development of a high-commitment organization to primarily focus on the interpersonal relationships with their subordinates.

Overall, our analysis draws attention to personnel and cultural controls as vital and indispensable stimuli to foster leadership impact on organizational commitment. The struggle for effective management control must therefore not be restricted to a ‘war of metrics’, i.e., finding the ideal financial key performance indicators for purposes of results control. Instead, top management has to focus on a comprehensive use of an organization’s management control system which aligns the ubiquitous formal controls with necessary informal means of control (Caldwell et al. 2011; Tucker 2010). Given our results, we further propose that the process of selecting and developing an organization’s top management should be accompanied by a focus on those characteristics that are correlated with the intended leadership style and the resulting choice of informal management control elements to enhance organizational commitment. Our results therefore extend the findings provided by Goebel and Weißenberger (2013), especially with respect to how CEOs and business unit heads use specific management controls.

Similar to other empirical works, our study is subject to a number of limitations. First, our results are based on survey data and therefore subject to potential biases associated with this approach. Although we employ appropriate procedural and statistical measures to account for this limitation, we remain careful in interpreting our results as these may still be affected by undetected biases. In order to assess a potential non-response bias, we perform Mann–Whitney U-tests for every construct of the questionnaire. The underlying assumption states that late respondents are expected to answer in a similar fashion to non-respondents (Armstrong and Overton 1977). A comparison of the latent variable scores of all variables shows no significant differences between the answers of early and late respondents, indicating that our results are probably not biased due to differences in response time (Henri 2006). As frequently proposed in psychology literature (e.g., Podsakoff et al. 2003; Podsakoff and Organ 1986), we employ Harman’s (1967) single-factor test to identify a potential common method variance. Based on exploratory factor analysis, none of the extracted factors explains a larger proportion of the variance in the variables. The modeling of a common latent factor (Podsakoff et al. 2003) supports our assumption as none of the factor loadings of this variable shows significant results (Liang et al. 2007). Given a very small magnitude of common method variance, we believe that our results are probably not compromised by a common method bias. Second, our research design is not qualified to rule out any issues of potential endogeneity. As the manifestation of a specific leadership style and the use of management control systems are influenced by a large number of individual and organizational characteristics, our research design may be subject to biases caused by omitted variables. For example, other variables, such as specific leader or follower demographics (e.g., age or tenure), leader personality, as well as industry effects might interfere with our results. In addition, we are not able to statistically rule out simultaneity issues or equilibrium conditions (Chenhall and Moers 2007). Although we believe that these effects are marginal at worst, we encourage future researchers to address this issue in greater detail. Third, our model may be subject to limitations associated with the calculation of second order constructs. Even though our results add to the existing body of knowledge on formal and informal control elements, an in-depth analysis of the isolated effects of results, action, personnel, and cultural controls could provide additional insights into the matter. We therefore strongly advise future researchers to pursue efforts herein. Finally, a large number of studies suggests that initiating structure and consideration are theoretically independent, although it has been found that this is not always true in an empirical sense. On the other hand, both dimensions are not redundant either. In our model, both dimensions correlate to an extent of 0.402 which is comparable to other studies in the field (Jugde et al. 2004). We therefore suggest that our measurement instruments are sufficiently separable.

Further research may also be warranted with respect to the classification of leadership styles. Although initiating structure and consideration cover many facets of the leadership puzzle, both dimensions can only draw an incomplete picture of all possible leadership behaviors (Jugde et al. 2004). Thus, further studies may be able to pursue our findings under different leadership classifications and consider leadership elements not discussed in our study. Despite these potential limitations, we are convinced that our study is a beneficial step towards a better understanding of how top managers, such as CEOs and business unit heads, use the various informal elements of an organization’s management control system as means to translate their leadership behavior into organizational commitment. We hope that our study opens the way for more detailed analyses of the influence of leadership styles on control choices as well as organizational outcomes.

References

Abernethy, M. A., & Brownell, P. (1997). Management control systems in research and development organizations: the role of accounting, behavior and personnel controls. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 22(3/4), 233–248.

Abernethy, M. A., & Chua, W. F. (1996). A field study of control system “redesign”: the impact of institutional process on strategic choice. Contemporary Accounting Research, 13(2), 569–606.

Abernethy, M. A., Bouwens, J., & Van Lent, L. (2010). Leadership and control system design. Management Accounting Research, 21(1), 2–16.

Achleitner, A. K., Kaserer, C., Kauf, T., Günther, N., & Ampenberger, M. (2009). Börsennotierte Familienunternehmen in Deutschland. München: Stiftung Familienunternehmen.

Albers, S. (2010). PLS and success factor studies in marketing. In V. Esposito Vinzi, W. W. Chin, J. Henseler, & H. Wang (Eds.), Handbook of partial least squares: concepts, methods and applications in marketing and related fields (pp. 409–425). Berlin et al.: Springer.

Anderson, R. C., & Reeb, D. M. (2003). Founding-family ownership and firm performance: evidence from the S &P 500. The Journal of Finance, 58(3), 1301–1327.

Anthony, R. N. (1965). Planning and control systems: a framework for analysis. Boston: Division of Research, Graduate School of Business Administration, Harvard University.

Armstrong, J. S., & Overton, T. S. (1977). Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research, 14(3), 396–402.

Auzair, S. M., & Langfield-Smith, K. (2005). The effect of service process type, business strategy and life cycle stage on bureaucratic MCS in service organizations. Management Accounting Research, 16(4), 399–421.

Bass, B. M. (1981). Handbook of leadership: a survey of theory and research. New York: Free Press.

Bass, B. M. (2008). The Bass handbook of leadership: theory, research, and managerial applications. New York: Free Press.

Becker, J., Klein, K., & Wetzels, M. (2012). Hierarchical latent variable models in PLS-SEM: guidelines for using reflective-formative type models. Long Range Planning, 45(5–6), 359–394.

Berry, A. J., Coad, A. F., Harris, E. P., Otley, D. T., & Stringer, C. (2009). Emerging themes in management control: a review of recent literature. The British Accounting Review, 41(1), 2–20.

Bisbe, J., & Otley, D. (2004). The effects of the interactive use of management control systems on product innovation. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 29(8), 709–737.

Bouillon, M. L., Ferrier, G. D., Stuebs, M. T., & West, T. D. (2006). The economic benefit of goal congruence and implications for management control systems. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 25(3), 265–298.

Brown, M. E., & Trevino, L. K. (2006). Ethical leadership: a review and future directions. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 595–616.

Brownell, P. (1983). Leadership style, budgetary participation and managerial behavior. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 8(4), 307–322.

Buchanan, B. (1974). Building organizational commitment: the socialization of managers in work organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 19(4), 533–546.

Caldwell, C., Truong, D. X., Linh, P. T., & Tuan, A. (2011). Strategic human resource management as ethical stewardship. Journal of Business Ethics, 98(1), 171–182.

Cardinal, L. B. (2001). Technological innovation in the pharmaceutical industry: the use of organizational control in managing research and development. Organization Science, 12(1), 19–36.

Chen, C. V., & Indartono, S. (2011). Study of commitment: the dynamic point of view. Journal of Business Ethics, 103(4), 529–541.

Chenhall, R. H. (2003). Management control systems design within its organizational context: findings from contingency-based research and directions for the future. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 28(2/3), 127–168.

Chenhall, R. H., & Moers, F. (2007). The issue of endogeneity within theory-based, quantitative, management accounting research. European Accounting Review, 16(1), 173–195.

Chenhall, R. H., Hall, M., & Smith, D. (2010). Social capital and management control systems: a study of a non-government organization. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 35(8), 737–756.

Chenhall, R. H., Kallunki, J.-P., & Silvola, H. (2011). Exploring the relationships between strategy, innovation, and management control systems: the roles of social networking, organic innovative culture, and formal controls. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 23, 99–128.

Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach for structural equation modeling. In G. A. Marcoulides (Ed.), Modern methods for business research (pp. 295–336). Mahway: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Chin, W. W., & Newsted, P. R. (1999). Structural equation modeling analysis with small samples using partial least squares. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Statistical Strategies for Small Sample Research (pp. 307–341). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Chong, V. K., & Eggleton, I. R. C. (2007). The impact of reliance on incentive-based compensation schemes, information asymmetry and organisational commitment on managerial performance. Management Accounting Research, 18(3), 312–342.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Cunningham, G. M. (1992). Management control and accounting systems under a competitive strategy. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 5(2), 85–102.

Dale, K., & Fox, M. L. (2008). Leadership style and organizational commitment: mediating effect of role stress. Journal of Managerial Issues, 20(1), 109–130.

Davila, A., & Foster, G. (2007). Management control systems in early-stage startup companies. The Accounting Review, 82(4), 907–937.

DeCotiis, T. A., & Summers, T. P. (1987). A path analysis of a model of the antecedents and consequences of organizational commitment. Human Relations, 40(7), 445–470.

Dent, J. F. (1990). Strategy, organization and control: some possibilities for accounting research. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 15(1/2), 3–25.

Dermer, J. D., & Lucas, R. G. (1986). The illusion of managerial control. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 11(6), 471–482.

DeRue, D. S., Nahrgang, J. D., Wellman, N. E., & Humphrey, S. E. (2011). Trait and behavioral theories of leadership: an integration and meta-analytic test of their relative validity. Personnel Psychology, 64(1), 7–52.

Fisher, J. G. (1995). Contingency-based research on management control systems: categorization by level of complexity. Journal of Accounting Literature, 14, 24–53.

Fisher, J. G. (1998). Contingency theory, management control systems and firm outcomes: past results and future directions. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 10(Supplement), 47–64.

Flamholtz, E. G., Das, T. K., & Tsui, A. S. (1985). Toward an integrative framework of organizational control. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 10(1), 35–50.

Fleishman, E. A. (1957). A leader behavior description for industry. In R. M. Stogdill & A. E. Coons (Eds.), Leader behavior: its description and measurement (pp. 103–119). Columbus: Ohio State University.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Fu, P. P., Tsui, A. S., Liu, J., & Li, L. (2010). Pursuit of whose happiness? Executive leaders’ transformational behaviors and personal values. Administrative Science Quarterly, 55(2), 222–254.

Geisser, S. (1974). A predictive approach to the random effect model. Biometrika, 61(1), 101–107.

Goebel, S., & Weißenberger, B. E. (2013). Effects of management control mechanisms: toward a more holistic analysis. Working paper: Justus Liebig University Gießen.

Govindarajan, V. (1984). Appropriateness of accounting data in performance evaluation: an empirical examination of environmental uncertainty as an intervening variable. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 9(2), 125–135.

Green, S. G., & Welch, M. A. (1988). Cybernetics and dependence: reframing the control concept. Academy of Management Review, 13(2), 287–301.

Gregson, T. (1992). An investigation of the causal ordering of job satisfaction and organizational commitment in turnover models in accounting. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 4, 80–95.

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–151.

Hair, J., Sarstedt, M., Pieper, T. M., & Ringle, C. M. (2012a). The use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in strategic management research: a review of past practices and recommendations for future applications. Long Range Planning, 45(5–6), 320–340.

Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Mena, J. A. (2012b). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(3), 414–433.

Halpin, A. W., & Winer, B. J. (1957). A factorial study of the leader behavior descriptions. In R. M. Stogdill & A. E. Coons (Eds.), Leader behavior: its description and measurement (pp. 39–51). Columbus: Ohio State University.

Hansen, S. C., Otley, D. T., & Van der Stede, W. A. (2003). Practice developments in budgeting: an overview and research perspective. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 15, 95–116.

Harman, H. H. (1967). Modern factor analysis (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hartmann, F., Naranjo-Gil, D., & Perego, P. (2010). The effects of leadership styles and use of performance measures on managerial work-related attitudes. European Accounting Review, 19(2), 275–310.

Henri, J. F. (2006). Organizational culture and performance measurement systems. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 31(1), 77–103.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. Advances in International Marketing, 20, 277–319.

Hopwood, A. G. (1974). Leadership climate and the use of accounting data in performance evaluation. The Accounting Review, 49(3), 485–495.

Hopwood, A. G. (2009). The economic crisis and accounting: implications for the research community. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 34(6/7), 797–802.

House, R. J., & Mitchell, T. R. (1974). Path-goal theory of leadership. Journal of Contemporary Business, 3(4), 81–97.

Hutzschenreuter, J. (2009). Management control in small and medium-sized enterprises: indirect control forms, control combinations and their effect on company performance. Wiesbaden: Gabler.

Iacobucci, D. (2010). Structural equations modeling: fit indices, sample size, and advanced topics. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 20(1), 90–98.

Jago, A. G. (1982). Leadership: perspectives in theory and research. Management Science, 28(3), 315–336.

Jansen, E. P. (2011). The effect of leadership style on the information receivers’ reaction to management accounting change. Management Accounting Research, 22(2), 105–124.

Jaworski, B. J., & MacInnis, D. J. (1989). Marketing jobs and management controls: toward a framework. Journal of Marketing Research, 26(4), 406–419.

Jaworski, B. J., & Young, S. M. (1992). Dysfunctional behavior and management control: an empirical study of marketing managers. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 17(1), 17–35.

Jiambalvo, J., & Pratt, J. (1982). Task complexity and leadership effectiveness in CPA firms. The Accounting Review, 57(4), 734–750.

Johnson, J. P., Korsgaard, M. A., & Sapienza, H. J. (2002). Perceived fairness, decision control, and commitment in international joint venture management teams. Strategic Management Journal, 23(12), 1141–1160.

Jugde, T. A., Piccolo, R. F., & Ilies, R. (2004). The forgotten ones? The validity of consideration and initiating structure in leadership research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(1), 36–51.

Kida, T. E. (1984). Performance evaluation and review meeting characteristics in public accounting firms. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 9(2), 137–147.

Kyj, L., & Parker, R. J. (2008). Antecedents of budget participation: leadership style, information asymmetry, and evaluative use of budget. Abacus, 44(4), 423–442.

Kotter, J. P. (1990). A force for change: how leadership differs from management. New York: Free Press.

Kren, L., & Kerr, J. L. (1993). The effect of behaviour monitoring and uncertainty on the use of performance-contingent compensation. Accounting and Business Research, 23(90), 159–168.

Law, K. S., Wong, C., & Mobley, W. H. (1998). Toward a taxonomy of multidimensional constructs. Academy of Management Review, 23(4), 741–755.

Lee, L., Petter, S., Fayard, D., & Robinson, S. (2011). On the use of partial least squares path modeling in accounting research. International Journal of Accounting Information Systems, 12(4), 305–328.

Liang, H., Saraf, N., Hu, Q., & Xue, Y. (2007). Assimilation of enterprise systems: the effect of institutional pressures and the mediating role of top management. MIS Quarterly, 31(1), 59–87.

Libby, T., & Waterhouse, J. H. (1996). Predicting change in management accounting systems. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 8, 137–150.

Luft, J., & Shields, M. D. (2003). Mapping management accounting: graphics and guidelines for theory-consistent empirical research. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 28(2/3), 169–249.

Luthans, F., Baack, D., & Taylor, L. (1987). Organizational commitment: analysis of antecedents. Human Relations, 40, 219–236.

Machin, J. L. (1979). A contingent methodology for management control. Journal of Management Studies, 16(1), 2–29.

Macintosh, N. B., & Daft, R. L. (1987). Management control systems and departmental interdependencies: an empirical study. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 12(1), 49–61.

Malmi, T., & Brown, D. A. (2008). Management control systems as a package: opportunities, challenges and research directions. Management Accounting Research, 19(4), 287–300.

Marginson, D. E. W. (1999). Beyond the budgetary control system: towards a two-tiered process of management control. Management Accounting Research, 10(3), 203–230.

Mathieu, J. E., & Zajac, D. M. (1990). A review and meta-analysis of the antecedents, correlates, and consequences of organizational commitment. Psychological Bulletin, 108(2), 171–194.

Merchant, K. A. (1985). Organizational control and discretionary program decision making: a field study. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 10(1), 67–85.

Merchant, K. A. (1990). The effects of financial controls on data manipulation and management myopia. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 15(4), 297–313.

Merchant, K. A., & Manzoni, J. F. (1989). The achievability of budget targets in profit centers: a field study. The Accounting Review, 64(3), 539–558.

Merchant, K. A., & Van der Stede, W. A. (2012). Management control systems: performance measurement, evaluation and incentives (3rd ed.). Harlow: Prentice Hall.

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1987). A longitudinal analysis of the early development and consequences of organizational commitment. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement, 19(2), 199–215.

Meyer, J. P., Stanley, D. J., Herscovitch, L., & Topolnytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: a meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61(1), 20–52.

Morris, J. H., & Sherman, J. D. (1981). Generalizability of an organizational commitment model. Academy of Management Journal, 24(3), 512–526.

Morris, J., & Steers, R. (1980). Structural influences on organizational commitment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 17(1), 50–57.

Morsing, M., & Oswald, D. (2009). Sustainable leadership: management control systems and organizational culture in Novo Nordisk A/S. Corporate Governance, 9(1), 83–99.

Mowday, R. T., Porter, L. W., & Steers, R. M. (1982). Organizational linkage: the psychology of commitment, absenteeism and turnover. New York: Academic Press.

Mowday, R. T., Steers, R. M., & Porter, L. W. (1979). The measurement of organizational commitment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 14(2), 224–247.

Noeverman, J., & Koene, B. A. S. (2000). Evaluation and leadership: an explorative study of differences in evaluative style. Maandblad voor Accountancy en Bedrijfseconomie, 74, 62–76.

O’Clock, P., & Devine, K. (2003). The role of strategy and culture in the performance evaluation of international strategic business units. Management Accounting Quarterly, 4(2), 18–26.

Otley, D. T. (1980). The contingency theory of management accounting: achievement and prognosis. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 5(4), 413–428.

Otley, D. T., & Pierce, B. J. (1995). The control problem in public accounting firms: an empirical study of the impact of leadership style. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 20(5), 405–420.

Ouchi, W. G. (1977). The relationship between organizational structure and organizational control. Administrative Science Quarterly, 22(1), 95–113.

Ouchi, W. G. (1979). A conceptual framework for the design of organizational control mechanisms. Management Science, 25(9), 833–848.

Pfeffer, J. (1998). Six dangerous myths about pay. Harvard Business Review, 76(3), 109–119.

Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1986). Self reports in organizational research: problems and prospects. Journal of Management, 12(4), 531–544.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Bommer, W. H. (1996). Transformational leader behaviors and substitutes for leadership as determinants of employee satisfaction, commitment, trust, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Management, 22(2), 259–298.

Podsakoff, P. M., Mackenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Porter, L. W., Steers, R. M., Mowday, R. T., & Boulian, P. V. (1974). Organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover among psychiatric technicians. Journal of Applied Psychology, 59(5), 603–609.

Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., & Straub, D. W. (2012). A critical look at the use of PLS-SEM in MIS Quarterly. MIS Quarterly, 36(1), iii–xiv.

Sandelin, M. (2008). Operation of management control practices as a package. Management Accounting Research, 19(4), 324–343.

Schriesheim, C. A., & Kerr, S. (1974). Psychometric properties of the Ohio State leadership scales. Psychological Bulletin, 81(10), 756–765.

Seltzer, J., & Bass, B. M. (1990). Transformational leadership: beyond initiation and consideration. Journal of Management, 16(4), 693–703.

Selznick, P. (1957). Leadership in administration. New York: Harper & Row.

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7(4), 422–445.

Snell, S. A. (1992). Control theory in strategic human resource management: the mediating effect of administrative information. Academy of Management Journal, 35(2), 292–327.

Snell, S. A., & Youndt, M. A. (1995). Human resource management and firm performance: testing a contingency model of executive controls. Journal of Management, 21(4), 711–737.

Sobel, M. E. (1982). Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In S. Leinhart (Ed.), Sociological methodology (pp. 290–313). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Steers, R. M. (1977). Antecedents and outcomes of organizational commitment. Administrative Science Quarterly, 22(1), 46–56.

Stogdill, R. M. (1963). Manual for the Leader Behavior Description Questionnaire - Form XII. Columbus: Ohio State University.

Stone, M. (1974). Cross-validatory choice and assessment of statistical predictions. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 36(2), 111–147.

Strauß, E., & Zecher, C. (2013). Management control systems: a review. Journal of Management Control, 23(4), 233–268.

Tucker, B. (2010). Heard it through the grapevine: a small-worlds perspective in control as a package. Working paper: University of South Australia.

Villalonga, B., & Amit, R. (2009). How are U.S. family firms controlled? The Review of Financial Studies, 22(8), 3047–3091.

Waldman, D. A., Ramirez, G. G., House, R. J., & Puranam, P. (2001). Does leadership matter? CEO leadership attributes and profitability under conditions of perceived environmental uncertainty. Academy of Management Journal, 44(1), 134–143.

Wargitsch, C. (2010). Management Control in Familienunternehmen. Frankfurt a.M.: Lang.

Wetzels, M., Oderken-Schröder, G., & Van Oppen, C. (2009). Using PLS path modeling for assessing hierarchical construct models: guidelines and empirical illustration. MIS Quarterly, 33(1), 177–195.

Widener, S. (2004). An empirical investigation of the relation between the use of strategic human capital and the design of the management control system. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 29(3/4), 377–399.

Widener, S. (2007). An empirical analysis of the levers of control framework. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 32(7/8), 757–788.

Wofford, J. C., & Liska, L. Z. (1993). Path-goal theories of leadership: a meta-analysis. Journal of Management, 19(4), 857–876.

Yukl, G. A. (2013). Leadership in organizations (8th ed.). Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Questionnaire

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kleine, C., Weißenberger, B.E. Leadership impact on organizational commitment: the mediating role of management control systems choice. J Manag Control 24, 241–266 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00187-013-0181-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00187-013-0181-3