Abstract

This paper is the first to investigate the impact of the presence of a public firm on the profitability of two-firm mergers in a spatial price discrimination model. The presence of the public firm may increase the set of mergers for two private firms to profitably merge. Merger increases social welfare in the presence of a public follower alone. However, privatizing the public firm never increases social welfare.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Heywood and McGinty (2011) consider cross-border mergers in a mixed oligopoly, but under a non-spatial model.

Results are robust to the presence of excluded profit-maximizing firms, because the binding no-jump condition remains the same from the excluded public firm rather than the excluded private firm.

The Economist, “Mutually assured existence: Public and private banks have reached a modus Vivendi,” May 13, 2010.

Following the literature, a merger can take place only between two adjacent firms.

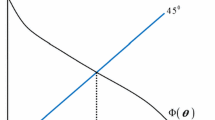

The no-jump condition guarantees that the follower has no incentive to jump to the leader’s corner. So, the leader would choose the location where the follower gets the same profit by jumping as by not jumping.

Note that the no-jump conditions from the private follower at the left corner are not binding.

References

Greenhut ML (1981) Spatial pricing in the United States, West Germany and Japan. Economica 48(189):79–86

Gupta B (1992) Sequential entry and deterrence with competitive spatial price discrimination. Econ Lett 38:487–490

Gupta B, Heywood JS, Pal D (1997) Duopoly, delivered pricing and horizontal mergers. South Econ J 63(3):585–593

Heywood JS, McGinty M (2011) Cross-border mergers in a mixed oligopoly. Econ Model 28(1):382–389

Heywood JS, Monaco K, Rothschild R (2001) Spatial price discrimination and merger: the N-firm case. South Econ J 67(3):672–684

Heywood JS, Ye G (2009) Mixed oligopoly, sequential entry, and spatial price discrimination. Econ Inq 47(3):589–597

Heywood JS, Ye G (2013) Sequential entry and merger in spatial price discrimination. Ann Reg Sci 50:841–859

Matsushima N, Matsumura T (2003) Mixed oligopoly and spatial agglomeration. Can J Econ 36(1):62–87

Matsumura T, Shimizu D (2010) Privatization waves. Manch Sch 78(6):609–625

Pepall L, Richards DJ, Norman G (1999) Industrial organization: contemporary theory and practice. South-Western College Pub., St. Paul

Reitzes JD, Levy DT (1995) Price discrimination and mergers. Can J Econ 28(2):427–436

Rothschild R, Heywood J, Monaco K (2000) Spatial price discrimination and the merger paradox. Reg Sci Urban Econ 30:491–506

Salant SW, Switzer S, Reynolds RJ (1983) Losses from horizontal merger: the effects of an exogenous change in industry structure on Cournot-Nash equilibrium. Quart J Econ 98(2):185

Thisse JF, Vives X (1988) On the strategic choice of spatial price policy. Am Econ Rev 78(1):122–137

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the Chinese National Natural Science Foundation (No. 71273270 and No. 71133006), the Fok Ying Tung Education Foundation (No. 141082), the Fundamental Research Funds for Central Universities and the Research Fund of Renmin University (No. 14XNI006) is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Proof of Proposition 1

When there is no merger between private firms, the equilibrium profits and welfare become \(\Pi _{1}^{N}=0.105t\), \(\Pi _{2}^{N}=0.038t\), \(W^{N}=r-0.095t\) (Heywood and Ye 2009).

(1) For \(\alpha \in [0,0.672]\), solving \(\Pi _1^N -\Pi _1^M =0\) generates a unique root \(\alpha =0.432\). It is easy to verify that \(\Pi _1^N \le \Pi _1^M \)for \(\alpha \in [0.432,1]\). And,

\(\frac{\partial (\Pi _2^M -\Pi _2^N )}{\partial \alpha }=-\frac{4\left( {2-\alpha } \right) \left( {3-2\alpha } \right) \left( {2\alpha ^{5}+\alpha ^{4}-55\alpha ^{3}+264\alpha ^{2}-648\alpha +576} \right) }{\left( {48-48\alpha +17\alpha ^{2}-\alpha ^{3}} \right) ^{3}}<0;\) thus, at the edge of the range \(\Pi _2^M -\Pi _2^N |_{\alpha =0.672} =0.046t>0\), proving that \(\Pi _2^M >\Pi _2^N \) for \(\alpha \in [0.432,0.672]\). For \(\alpha \in [0.672,1]\),\(\frac{\partial (\Pi _2^M -\Pi _2^N )}{\partial \alpha }<0\), and the profit difference reaches its minimum at \(\Pi _2^M -\Pi _2^N |_{\alpha =1} =0\), implying that \(\Pi _2^M \ge \Pi _2^N \). Exact expressions for the constrained case are available upon request.

(2) For \(\alpha \in [0.432,0.672]\), solving

\(\frac{\partial \left( {W^{M}-W^N} \right) }{\partial \alpha }=\frac{2\left( {5040\alpha -8280\alpha ^{2}+7229\alpha ^{3} -3662\alpha ^{4}+1116\alpha ^{5}-199\alpha ^{6}+16\alpha ^{7}-1152} \right) }{\left( {-48+48\alpha -17\alpha ^{2}+\alpha ^{3}} \right) ^{3}}=0\) generates \(\alpha =0.493\). It can be confirmed that \(\frac{\partial \left( {W^{M}-W^N } \right) }{\partial \alpha }>0\) when \(\alpha \in [0.432,0.493]\), and \(\frac{\partial \left( {W^{M}-W^N } \right) }{\partial \alpha }<0\) when \(\alpha \in [0.493,0.672]\). Thus, the welfare difference reaches its maximum at \(W^{M}-W^{N}|_{\alpha =0.493} =-0.003t\), implying that \(W^{M}<W^{N}\). Similarly, for \(\alpha \in [0.672,1]\), \(\frac{\partial \left( {W^{M}-W^N } \right) }{\partial \alpha }>0\), and the welfare difference reaches its maximum at \(W^{M}-W^{N}|_{\alpha =1} =0\), implying that \(W^{M}\le W^{N}\) for \(\alpha \in [0.672,1]\).

Proof of Proposition 2

When there is no merger between private firms, the public firm locates at the middle and the equilibrium profits and welfare become \(\Pi _1^N =t/12\), \(\Pi _3^N =t/12\), \(W^{N}=r-t/12\) (Heywood and Ye 2009).

(1) From above, we know that \(\Pi _1^N \le \Pi _1^M \) for \(\alpha \in [0.325,1]\). For \(\alpha \in [0.325,1]\), solving \(\Pi _3^N =\Pi _3^M \) generates a unique root \(\alpha =0.640\). It can be confirmed that \(\Pi _1^N \le \Pi _1^M \) and \(\Pi _3^N \le \Pi _3^M\) when \(\alpha \in [0.325, 640]\). Thus, private firms would always merge when \(\alpha \in [0.325, 640]\).

(2) For \(\alpha \in [0.325,0.640]\),

\(\frac{\partial \left( {W^{M}-W^N } \right) }{\partial \alpha }=\frac{3791\alpha -7446\alpha ^{2}+7396\alpha ^{3}-4036\alpha ^{4} +1335\alpha ^{5}-270\alpha ^{6}+26\alpha ^{7}-816}{\left( {-34+33\alpha -14\alpha ^{2}+\alpha ^{3}} \right) ^{3}}>0;\) thus, the welfare difference reaches its maximum at \(W^{M}-W^{N}|_{\alpha =0.640} =-0.012t\), implying that \(W^{M}<W^{N}\) for \(\alpha \in [0.325,0.640]\).

Proof of Proposition 3

When there is no merger between two private firms, the public firm locates at the middle and the equilibrium profits and welfare become \(\Pi _1^N =0.075t\), \(\Pi _2^N =0.075t\), \(W^{N}=r-0.101t\) (Heywood and Ye 2009).

(1) For \(\alpha \in [0, 1]\), solving \(\Pi _1^N =\Pi _1^M \) generates a unique root \(\alpha =0.119\); solving \(\Pi _2^N =\Pi _2^\mathrm{M}\) generates a unique root \(\alpha =0.783\). Then, \(\Pi _1^N \le \Pi _1^M\) for \(\alpha \in [0.119, 1]\), \(\Pi _2^N \le \Pi _2^\mathrm{M}\), for \(\alpha \in [0, 0.783]\). Thus, private firms would merge when \(\alpha \in [0.119, 0.783]\).

(2) For \(\alpha \in [0.119,0.783]\), solving

\(\frac{\partial \left( {W^{M}-W^N } \right) }{\partial \alpha }=\frac{2\left( {-423\alpha +558\alpha ^{2}-404\alpha ^{3} +72\alpha ^{4}+90} \right) }{\left( {30-15\alpha +2\alpha ^{2}} \right) ^{3}}=0\) generates \(\alpha =0.316\). It can be confirmed that \(\frac{\partial \left( {W^{M}-W^N } \right) }{\partial \alpha }>0\) when \(\alpha \in [0.119,0.316]\), and \(\frac{\partial \left( {W^{M}-W^N} \right) }{\partial \alpha }<0\) when \(\alpha \in [0.316,0.783]\). Thus, the welfare difference reaches its minimum at \(\alpha =0.119\) or \(\alpha =0.783\), and we find that \(W^{M}-W^{N}|_{\alpha =0.119} =0.015t\), \(W^{M}-W^{N}|_{\alpha =0.783} =0.012t\), implying that \(W^{M}>W^{N}\) for \(\alpha \in [0.119,0.783]\).

Proof of Proposition 4

(1) From Heywood and Ye (2013), the range of profitable mergers without a public firm is \(\alpha \in [0.440,1]\) . Therefore, the presence of a public firm increases the range of profitable mergers from \(\alpha \in [0.440,1]\) to \(\alpha \in [0.432,1]\).

(2) By comparing post-merger welfare with a public firm to that of pure triopoly in Heywood and Ye (2013), we can find that privatization always decreases social welfare. For \(\alpha \in [0,0.432]\), there is no merger between private firms in both pure private and mixed oligopoly cases. We have \(W^{PUB}-W^{PRI} =0.0036t>0\), where superscript PUB denotes the case with a public firm and superscript PRI denotes the case after privatization.

For \(\alpha \in [0.432,0.672]\), the private leader merges with the private follower and NJC from the public firm is not binding.

-

(1)

For \(\alpha \in [0.432,0.440]\), firms in the pure private case still have no incentives to merge and it can be confirmed that in range \(\alpha \in [0.432,0.672]\),

\(\frac{\partial (W^{PUB} -W^{PRI} )}{\partial \alpha }=-\frac{2\left( {-1152+5040\alpha +7229\alpha ^{3}-199\alpha ^{6}+ 1116\alpha ^{5}-3662\alpha ^{4}-8280\alpha ^{2}+16\alpha ^{7}} \right) }{\left( {48-48\alpha +17\alpha ^{2}-\alpha ^{3}} \right) ^{3}}>0;\) thus, at the edge of the range \(W^{PUB}-W^{PRI} |_{\alpha =0.432} =0.0036t>0\), proving that \(W^{PUB}-W^{PRI} >0\) for \(\alpha \in [0.432,0.440]\).

-

(2)

For \(\alpha \in [0.440,0.672]\), merger takes place in both with or without a public firm and no NJC is binding. Thus, \(W^{PUB}-W^{PRI} =0\).

For \(\alpha \in [0.672,1]\), the private leader merges with the private follower and NJC from the public firm is binding.

-

(1)

For \(\alpha \in [0.672,0.767]\), merger takes place in both cases and NJCs in the pure private case are not binding. It can be confirmed that \(\frac{\partial \left( {W^{PUB}-W^{PRI} } \right) }{\partial \alpha }>0\) when \(\alpha \in [0.672,0.767]\); thus, the welfare difference reaches its minimum at \(W^{PUB}-W^{PRI}|_{\alpha =0.672} =0\), implying that \(W^{PUB}-W^{PRI} >0\) for \(\alpha \in (0.672,0.767]\).

-

(2)

For \(\alpha \in [0.767,1]\), firms in both cases would merge and NJCs are binding in both cases. It can be confirmed that \(\frac{\partial \left( {W^{PUB}-W^{PRI} } \right) }{\partial \alpha }=0\) when \(\alpha =0.886\), \(\frac{\partial \left( {W^{PUB}-W^{PRI} } \right) }{\partial \alpha }<0\) when \(\alpha \in [0.767,0.886]\), and \(\frac{\partial \left( {W^{PUB}-W^{PRI} } \right) }{\partial \alpha }>0\) when \(\alpha \in [0.886,1]\). Thus, the welfare difference reaches its minimum at \(W^{PUB}-W^{PRI}|_{\alpha =0.886} =0.0027t\), implying that \(W^{PUB}-W^{PRI} >0\).

Exact expressions are available upon request.

Proof of Proposition 5

(1) The range of profitable mergers without a public firm is \(\alpha \in [0.515, 1]\) (Heywood and Ye 2013). Therefore, the presence of a public firm decreases the range of profitable mergers from \(\alpha \in [0.515, 1]\) to \(\alpha \in [0.325, 640]\).

(2) By comparing welfare with a public firm to that of pure triopoly (Heywood and Ye 2013), we find that privatization always decreases social welfare.

For \(\alpha \in [0,0.325]\), there is no merger between private firms. \(W^{PUB}-W^{PRI} =0.018t>0\).

For \(\alpha \in [0.325,0.640]\), the private leader merges with the private follower and NJC from the public firm is not binding.

-

(1)

For \(\alpha \in [0.325,0.515]\), firms in the pure private case still have no incentives to merge. And it can be confirmed that in range \(\alpha \in [0.325,0.515]\),

\(\frac{\partial (W^{PUB} -W^{PRI} )}{\partial \alpha }=\frac{-816+26\alpha ^{7}-4036\alpha ^{4}+7396\alpha ^{3} -7446\alpha ^{2}+3791\alpha +1335\alpha ^{5}-270\alpha ^{6}}{\left( {\alpha ^{3}-14\alpha ^{2}+33\alpha -34} \right) ^{3}}>0;\) thus, at the edge of the range \(W^{PUB}-W^{PRI} |_{\alpha =0.325} =0.003t>0\), proving that \(W^{PUB}-W^{PRI} >0\) for \(\alpha \in [0.325,0.515]\).

-

(2)

For \(\alpha \in [0.515,0.640]\), firms in both cases would merge and NJCs are all not binding. It can be confirmed that \(\frac{\partial \left( {W^{PUB}-W^{PRI} } \right) }{\partial \alpha }<0\) when \(\alpha \in [0.515,0.640]\); thus, the welfare difference reaches its minimum at \(W^{PUB}-W^{PRI}|_{\alpha =0.640} =0.022t\), implying that \(W^{PUB}-W^{PRI} >0\) for \(\alpha \in [0.515,0.640]\).

For \(\alpha \in [0.640,1]\), merger does not occur in the mixed oligopoly case.

-

(1)

For \(\alpha \in [0.640,0.749]\), firms in the pure private case still have incentives to merge. It can be confirmed that \(\frac{\partial \left( {W^{PUB}-W^{PRI} } \right) }{\partial \alpha }<0\) when \(\alpha \in [0.640,0.749]\); thus, the welfare difference reaches its minimum at \(W^{PUB}-W^{PRI}|_{\alpha =0.749} =0.030t\), implying that \(W^{PUB}-W^{PRI} >0\) for \(\alpha \in [0.640,0.749]\).

-

(2)

For \(\alpha \in [0.749,1]\), firms in the pure private case still have incentives to merge and NJC from firm 3 to firm 2’s right corner is binding. Similarly, \(\frac{\partial \left( {W^{PUB}-W^{PRI} } \right) }{\partial \alpha }<0\) when \(\alpha \in [0.749,1]\); thus, the welfare difference reaches its minimum at \(W^{PUB}-W^{PRI}|_{\alpha =1} =0.015t\), implying that \(W^{PUB}-W^{PRI} >0\) for \(\alpha \in [0.749,1]\).

Proof of Proposition 6

(1) The range of profitable mergers without a public firm is \(\alpha \in [0.119, 0.783]\) (Heywood and Ye 2013). Therefore, the presence of a public firm has no impact on the range of profitable mergers \(\alpha \).

(2) The welfare with a public firm is the same as that of pure triopoly (Heywood and Ye 2013) because the locations of firms are not affected by the presence of a public firm.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ye, G., Wu, W. Privatization and merger in a mixed oligopoly with spatial price discrimination. Ann Reg Sci 54, 561–576 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-015-0666-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-015-0666-0