Abstract

This paper explores the labor market and schooling effects of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) initiative, which provides work authorization to eligible immigrants along with a temporary reprieve from deportation. The analysis relies on a difference-in-differences approach which exploits the discontinuity in program rules to compare eligible individuals to ineligible, likely undocumented immigrants before and after the program went into effect. To address potential endogeneity concerns, we focus on youths that likely met DACA’s schooling requirement when the program was announced. We find that DACA reduced the probability of school enrollment of eligible higher-educated individuals, as well as some evidence that it increased the employment likelihood of men, in particular. Together, these findings suggest that a lack of authorization may lead individuals to enroll in school when working is not a viable option. Thus, once employment restrictions are relaxed and the opportunity costs of higher education rise, eligible individuals may reduce investments in schooling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

DACA eligibility rules are outlined in Sect. 2 below.

Given the policy significance of DACA, interested parties have begun surveying DACA applicants to measure its impacts. Notably, Gonzales and Bautista-Chavez (2014) report that almost 60 percent of survey respondents found a new job, even though most were already at work prior to DACA. School enrollment effects are not reported. Nonetheless, lack of information on the selection of survey participants and on survey non-response rates make it difficult to compare their findings with those reported here.

It may be seen in other labor market outcomes, however, such as wages and type of occupation. We also explore these outcomes below.

This is analogous to the explanation offered in Charles et al. (2013), who suggest that housing booms resulted in an increase in the opportunity cost of college and thus an observed drop in enrollments at community colleges. Similar effects of local labor market conditions on educational attainment are found in Evans and Kim (2008) and Black et al. (2005).

For greater details, visit the section entitled: “Consideration of deferred action for childhood arrivals process” at http://www.uscis.gov.

Our results are substantially similar if we use a slightly older age cutoff and restrict the sample to individuals ages 20 to 24 with a high school or GED degree. Nevertheless, we present the results for the larger group of 18- to 24-year olds with a high school degree or GED to preserve sample size.

For example, we place “computer and mathematical sciences occupations” in the high-skill category and “food preparation and serving related occupations” in the low-skill category. The full classification of occupations into high and low skill can be found in Appendix 1.

Foreign students with F1 and J1 visas are allowed to stay in the USA for the duration of the academic program they are admitted to, which is typically listed in the arrival-departure Form I-94 (now automated). If no specific date is listed in the I-94 Form, their admission stamp will indicate: duration of status (“D/S”), and they will be allowed to stay in the USA as long as they are pursuing a full course of study (12 units for undergraduates/8 units for graduates per semester) and making normal progress toward completing their academic program. The I-20 for F1 students and the DS-156 for J1 students tell exactly how long the academic program will take.

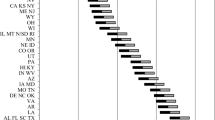

These states are California, Texas, New York, Illinois, Florida, North Carolina, Arizona, Georgia, and New Jersey.

Note that the inclusion of month-year fixed effects implies the main level effect of DACA (DACA t ) drops out of the equation due to multicollinearity.

While we limit the sample to a more educated group for reasons noted above, some may nevertheless be interested in results for the full sample without the restriction on education, particularly given that undocumented immigrants are likely to be less educated. Thus, we present results of estimating Eq. (1) on the full sample without the schooling restriction in Appendix 2. Note that an additional control for schooling level is added since the sample includes both higher- and less-educated individuals. As can be seen from Appendix 2, results are substantially similar to those in Tables 3 and 4.

This finding is in line with those from prior studies examining the impact of legalization under the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) on labor market outcomes concluding that the latter improved undocumented workers’ employment prospects, reduced their workplace vulnerabilities, or increased their job mobility and working conditions (Rivera-Batiz 1999; Kossoudji and Cobb-Clark 2002; Amuedo-Dorantes et al. 2007).

We are unable to exploit the discontinuity in age at the time of DACA’s announcement (eligibility requirement number 1 above) because the survey only asks schooling questions of respondents between the ages of 16 and 24.

Each of these placebo indicators runs from October of the year of interest through the following September to match the timing of the DACA indicator discussed in Sect. 2.

As in Table 5, to mirror the timing of DACA, the new placebo indicator runs from October of the year of interest (October 2009) and, in this case, spans to the end of 2011.

References

Amuedo-Dorantes C, Bansak C, Raphael S (2007) Gender differences in the labor market: impact of IRCA’s amnesty provisions. Am Econ Rev 97(2):412–416

Batalova J, Hooker S, Capps R (2013) Deferred action for childhood arrivals at the one-year mark, issue brief, no. 8, august. Migration Policy Institute, Washington DC

Black DA, McKinnish TG, Sanders SG (2005) Tight labor markets and the demand for educational attainment: evidence from the coal boom and bust. Ind Labor Relat Rev 59(1):3–16

Charles KK, Hurst E, Notowidigdo MJ (2013) Housing booms, labor market outcomes, and educational attainment. Unpublished manuscript. University of Chicago, Booth School of Business

Constant A, Zimmermann KF (2005a) Immigrant performance and selective immigration policy: a European perspective. Natl Instit Econ Rev 194(1):94–105

Constant A, Zimmermann KF (2005b) Legal status at entry, economic performance, and self-employment proclivity: a bi-national study of immigrants. IZA Discussion Paper No. 1910

Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (2013) Deferred action for childhood arrivals. Data for August 2012–30 June 2013. Available at: www.uscis.gov/USCIS/Resources/Reports%20and%20Studies/Immigration%20Forms%20Data/All%20Form%20Types/DACA/daca-13-7-12.pdf

Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (2015) Biometrics capture systems, CIS consolidated operational repository (CISCOR)

Evans WN, Kim W-Y (2008) The impact of local labor market conditions on the demand for educational attainment: evidence from Indian casinos. Unpublished manuscript, University of Notre Dame

Gathmann C, Keller N (2013) Benefits of citizenship? evidence from Germany’s new immigration policy. Unpublished manuscript, University of Heidelberg

Gonzales RG, Bautista-Chavez AM (2014) Two years and counting: assessing the growing power of DACA. American Immigration Council Report

Immigration Policy Center (2012) Creating opportunity: the economic benefits of granting deferred action to unauthorized immigrants brought to the United States as Children, Washington, DC: June 22

Kossoudji SA, Cobb-Clark DA (2002) Coming out of the shadows: learning about legal status and wages from the legalized population. J Labor Econ 20(3):598–628

National Immigration Law Center (2005) The economic benefits of the DREAM act and the student adjustment act, Washington, DC: February

Passel JS, Cohn D (2009) A portrait of unauthorized immigrants in the United States. Pew Hispanic Center, Washington, DC

Passel J, Cohn DV (2010) U.S. unauthorized immigration flows are down sharply since mid‐decade. Pew Hispanic Center, Washington, DC

Passel J, Lopez MH (2012) Up to 1.7 million unauthorized immigrant youth may benefit from new deportation rules. Pew Hispanic Center, Washington, DC

Passel JS, Cohn D, Gonzalez-Barrera A (2013) Population decline of unauthorized immigrants stalls, may have reversed. Pew Research Center, Washington, DC

Preston J, Cushman Jr. JH (2012) Obama to permit young migrants to remain in U.S. The New York Times. Published June 15, 2012. Accessed September 24, 2013

Rivera-Batiz F (1999) Undocumented workers in the labor market: an analysis of the earnings of legal and illegal Mexican immigrants in the United States. J Popul Econ 12(1):91–116

Singer A, Svajlenka NP (2013) Immigration facts: deferred action for childhood arrivals (DACA). Brookings Institution. 14 August 2013. Available at: http://www.brookings.edu/research/reports/2013/08/14-daca-immigration-singer

Wallsten P (2012) Marco Rubio’s DREAM act alternative a challenge for Obama on illegal immigration. The Washington Post. Published 25 April2012. Accessed 26 September 2013

Wong TK, García AS, Abrajano M, FitzGerald D, Ramakrishnan K, Le S (2013) Undocumented no more: a nationwide analysis of deferred action for childhood arrivals, or DACA. Center for American Progress, Washington, DC

Acknowledgments

We thank Kelly Bedard, Sarah Bohn, Brian Cadena, Seema Jayachandran, Terra McKinnish, Anita Alves Pena, Audrey Singer, Stephen J. Trejo, Klaus Zimmermann, three anonymous referees, seminar participants at the IZA Annual Migration Meeting, University of Southern California and Colegio de la Frontera, along with session participants at the annual meetings of the American Economic Association, Population Association of America and Western Economic Association International. Any errors are our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Responsible editor: Klaus F. Zimmermann

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Amuedo-Dorantes, C., Antman, F. Schooling and labor market effects of temporary authorization: evidence from DACA. J Popul Econ 30, 339–373 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-016-0606-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-016-0606-z