Abstract

We estimate the effects of labor market entry conditions on wages for male individuals first entering the Austrian labor market between 1978 and 2000. We find a large negative effect of unfavorable entry conditions on starting wages and a sizable negative long-run effect. Our preferred estimates imply a decrease in starting wages by about 0.9 % and a lifetime loss in wages of about 1.3 % for an increase in the initial local unemployment rate by one percentage point. We show that poor entry conditions are associated with lower quality of a worker’s first employer and that the quality of workers’ first employer explains as much as three-quarters of the observed long-run wage effects resulting from poor entry conditions. Moreover, wage effects are much more persistent for blue-collar workers because some of them appear to be permanently locked in into low-paying jobs/tasks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Most studies estimating the short-run association between fluctuations in local unemployment rates and wages find that wages vary negatively with local unemployment. This negative association is a very robust empirical pattern; it has been shown to exist for a wide range of different countries, using very different sources of data and diverse empirical specifications. See Nijkamp and Poot (2005) for a comprehensive survey of this literature.

Previous research has shown that the early years in a worker’s labor market career are of special importance (Gardecki and Neumark 1998; Neumark 2002). In terms of wages, Murphy and Welch (1990) estimate that almost 80 % of all (i.e., lifetime) wage increases accrue within the first 10 years of labor market experience. Moreover, movements across jobs are considerably more likely at the beginning of a worker’s career than later on (Topel and Ward 1992).

Various dimensions other than wages may be influenced by conditions at labor market entry. For example, Giuliano and Spilimbergo (2009) show that entry conditions have long-lasting effects on individuals’ beliefs and preferences, while Kondo (2012) finds that the timing of marriage of both men and women is influenced by entry conditions.

One important concern regarding the validity of these results is that schooling and first entry into the labor force may be endogenous both because individuals may choose to stay in school or continue further training when faced with high unemployment and low starting wages. Indeed, several studies find that enrollment rates are high when unemployment is high and the opportunity costs of schooling are low (Clark 2011). In line with these findings, both Kahn (2010) and Oreopoulos et al. (2012) find the duration of schooling to be endogenous. Both tackle the endogeneity problem by instrumenting the unemployment rate at the time of labor market entry with either the prevailing unemployment rate at a lower age or that in the predicted year of graduation. Mansour (2009) presents direct evidence on sample selection over the business cycle based on AFQT scores.

A similar analysis of wage effects for firm entry cohorts in the German manufacturing sector is given by von Wachter and Bender (2008). However, their analysis is not confined to new labor market entrants, but covers workers of all experience levels; their results are therefore not directly comparable to the other studies mentioned.

Note, however, that workers in the Austrian labor market typically have some, potentially very specialized, vocational training, as a significant part of the initial vocational training in Austria is provided by dual apprenticeship training schemes, i.e., practical training provided by firms coupled with part-time compulsory attendance at a vocational school. Apprenticeships last from 2 to 4 years, depending on occupation. Full-time vocational and technical schools provide an important alternative to apprenticeship training and also last up to 4 years. Details are available from the report by the Federal Ministry for Education, the Arts and Culture (2008).

Consistent with this line of argument, Kwon et al. (2010) find that workers who enter the labor market during a boom are promoted more quickly and to higher ranks than those who enter during a recession, and Mansour (2009) shows that workers entering in a recession are initially assigned to lower- paying jobs.

The Austrian Central Social Security Administration collects these data with the purpose of administering and calculating entitlements to old-age pension benefits. For this reason, the ASSD includes precise and comprehensive information on annual earnings and daily employment histories. However, contributions to the old-age pension system are capped because old-age pension benefits are limited to a maximum level. As a consequence, annual earnings are only recorded up to the threshold which guarantees the maximum benefit level (“Höchstbemessungsgrundlage”, HBGr). Similarly, there is a base threshold below which no (otherwise mandatory) social security payments accrue (“Geringfügigkeitsgrenze”, GfGr). The two censoring points vary over time in real terms: The lower censoring point increased from about 14 € in 1978 to about 26 € in 2005 (per day worked); the upper censoring point increased from about 78 € to 126 € per workday over the same period of time.

We decided to extract yearly male unemployment rates for the age groups 16 to 65 and 16 to 25, both at the state (“Bundesland”) level and at the common classification of territorial units for statistics (NUTS) level. At the NUTS level, we use the most disaggregated level available (NUTS-3), which corresponds to one or more political districts in Austria. There are total of nine different states and 35 different NUTS-3 regions in Austria. Yearly unemployment rates are within-year averages of monthly unemployment rates.

Because the ASSD does not contain a comprehensive measure for schooling, we use age at entry into the labor force as proxy for education in the regressions below. To mitigate potential collinearity with year of birth and year of entry, we use a slightly different variable as proxy in the regressions. Specifically, we use the smaller of age at start of first regular employment and age at start of first registered unemployment spell.

Several arguments motivate the restriction on schooling. First, the timing of first labor market entry, and thus the duration of schooling, may be endogenous. However, less-skilled workers are presumably less likely to manipulate the duration of schooling. Furthermore, unobserved heterogeneity resulting from, say, unobserved differences in inherent ability, is arguably a more urgent problem for workers with higher skills. Moreover, we believe that our proxy for schooling works best for workers with low education levels. Finally, only including less-skilled workers in the sample is an effective way of dealing with right-censored wages (see also the Appendix).

Wage profiles of different entry cohorts have somewhat distinct overall shapes. More specifically, the figure shows that returns to experience generally decrease over time, meaning that younger entry cohorts have considerably lower returns to labor market experience than older cohorts. For example, the 1995 cohort only realizes an average wage increase of about 58 % (= exp(. 46) − 1 · 100%) in the first 10 years, thus less smaller than that of the corresponding increase of the 1978 entry cohort.

For example, and as highlighted in the figure, Burgenland (located in southeastern Austria) experienced a huge increase in the unemployment rate from about 3 % in the late 1970s to about 8 % in the first half of the 1980s, and then to about 9 % in the second half of the 1980s. Vorarlberg (situated in western Austria), in contrast, experienced only a modest increase from about 1 % on the 1970s to about 3% in the 1980s. In 1992, however, Vorarlberg underwent a sharp decline in the local labor market conditions, when unemployment jumped from about 3 % to about 7–8 %.

Specifically, we include the first three polynomial terms of potential labor market experience. We chose the number of polynomial terms on the basis of a nonparametric, and therefore fully flexible, wage–experience model. The first three polynomial terms appear sufficient for reproducing the wage–experience profile that a corresponding nonparametric specification predicts.

We also computed standard errors that simultaneously account for clustering at both levels for our main estimates. This yields standard errors that are virtually indistinguishable from those actually reported.

Appendix Table 10 shows that only few wage observations are censored in the year of entry. However, top-censored wages become much more frequent as workers accumulate labor market experience.

It may also reflect endogeneity of the local unemployment rate at lower aggregation levels, due to the fact that workers move from regions with high unemployment to those with lower levels of unemployment (Wozniak 2010).

19Bils (1985) and more recently Solon et al. (1994) and Blundell et al. (2003) have put forth this line of argument. In fact, the timing of labor force entry and thus the composition of labor market cohorts may be endogenous for several distinct reasons. First, some potential labor market entrants may refrain from entering the labor market altogether. Second, both the choice of education as well as the duration of schooling may be endogenous, as both job prospects are weak and opportunity costs of schooling are low in times of high unemployment. Third, some workers may simply delay their entry when faced with unfavorable entry conditions, either by registering for unemployment benefits or by staying out of the labor force until they find a job. Whatever the underlying reason, if those workers who do not immediately get a job are a selected group of all workers who intend to enter employment in a given year, then the composition of the actual entrants changes along with corresponding changes in the unemployment rate and thus potentially biases the estimated effect of the initial unemployment rate on wages.

20Kahn (2010), Kondo (2008) and Oreopoulos et al. (2012) use a similar instrumental variable strategy. OLS and IV estimates are similar to those of Oreopoulos et al. (2012), but IV are substantially larger to those of both Kondo (2008) and Kahn (2010). Two European studies, by Kwon et al. (2010) and Stevens (2007), only show OLS estimates.

To the best of our knowledge, there is no relevant empirical evidence for Austria. However, Muehlemann et al. (2009) provide evidence consistent with this line of argument for Switzerland, which has an apprenticeship system very similar to that of Austria. Their results thus presumably carry over to Austria.

This result is perhaps not surprising because apprenticeship positions usually have a fixed duration of either 3 or 4 years. Thus, in principle, it may be possible to observe no change in the average length of schooling/training even if there is considerable downranking to lower paying jobs.

It is reassuring that the estimated coefficient on the proxy for schooling/training equals about 0.046 in our baseline specification (i.e., column 6 of Table 2), which is consistent with the reported external evidence on the returns on apprenticeship training in Austria.

In line with these findings, Mansour (2009) finds that the quality of a worker’s first job is lower when entry happens during high unemployment, even though cohorts entering during recession are positively selected.

See Gathmann and Schönberg (2010) for evidence on task-specific, Kambourov and Manovskii (2009) on occupation-specific, and Neal (1995) or Parent (2000) on industry-specific human capital. Sullivan (2010) provides evidence that both occupation- and industry-specific human capital are decisive in determining the level of wages.

The “disappearance” of a firm identifier does not necessarily coincide with a plant closure because a firm identifier may also disappear for other reasons (e.g., because of a take-over by another firm).

We further include controls for time-varying characteristics of initial employers in column 3, but these variables do not have much additional impact on the estimated wage effects on top of the fixed effects for first employer.

Note that these two groups do not exactly add up to the overall sample size because some employment spells cannot be uniquely identified as either blue or white collar (cf. Table 1).

This result is somewhat surprising because previous research has shown that white-collar workers in Austria suffer from much larger and more persistent wage losses from job displacement (Schwerdt et al. 2010). However, we use a totally different sample of workers than that of Schwerdt et al. (2010). Moreover, our study focuses on low- and medium-skilled labor market entrants who entered the labor force between 1978 and 2000, while Schwerdt et al. (2010) focus on prime age workers of any educational level who experienced a plant closure between 1982 and 1988.

We provide some additional evidence that appears to be consistent and complementary with this explanation in the Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM). These additional results show that the adjustment in employer quality is incomplete for blue-collar workers, notwithstanding an increase in job mobility in at least the first 5 years of their labor market career, and that there is a permanent increase in the risk of job displacement. These findings suggest that some blue-collar workers entering the labor force in an economic downturn are forced into, and persistently locked in, low-paying jobs and/or tasks.

Obviously, an individual must be covered by the ASSD in order to be included in the sample. An individual is covered by the ASSD if he or she is entitled to future social security benefits (typically old-age benefits) or has already claimed social security benefits before first entering the labor force. Typically, individuals “enter” the ASSD once they start working.

Importantly, vocational training such as apprenticeship training is not considered as regular employment (but as formal training).

The group of individuals who enter at a later age probably consists of two very different groups, who are indistinguishable from each other in the data. On the one hand, there are truly high-skilled workers who enter the labor market at a later stage because they continued their education until that time. On the other hand, however, there are also low-skilled workers who were never employed or only sporadically employed before starting their first regular employment. Because schooling is not directly observed, we would mix these two groups of workers together if we were to include them.

References

Angrist J, Krueger A (1994) Why do World War II veterans earn more than nonveterans? J Labor Econ 12(1):74–97

Bils MJ (1985) Real wages over the business cycle: evidence from panel data. Polit Econ 93(4):666–689

Blanchflower DG, Oswald AJ (1990) The wage curve. Scand J Econ 92(2):215–235

Blundell R, Reed H, Stoker TM (2003) Interpreting aggregate wage growth: the role of labor market participation. Am Econ Rev 93(4):1114–1131

Burgess S, Propper C, Rees H, Shearer A (2003) The class of 1981: the effects of early career unemployment on subsequent unemployment experiences. Labour Econ 10(3):291–309

Clark D (2011) Do recessions keep students in school? The impact of youth unemployment on enrolment in post-compulsory education in England. Economica 78(311):523–545

Devereux PJ (2000) Task assignment over the business cycle. J Labor Econ 18(1):98–124

Elsby MW, Hobijn B, Şahin A (2010) The labor market in the great recession. Brookings Pap Eco Ac 2010(1):1–48

Federal Ministry for Education, the Arts and Culture (2008) Development of Education in Austria, 2004–2007. Federal Ministry for Education, the Arts and Culture, Vienna

Fersterer J, Pischke J, Winter-Ebmer R (2008) Returns to apprenticeship training in Austria: evidence from failed firms. Scand J Econ 110(4):733–753

Frühwirth-Schnatter S, Pamminger C, Weber A, Winter-Ebmer R (2011) Labor market entry and earnings dynamics: Bayesian inference using mixtures-of-experts Markov chain clustering. J Appl Econom 27(7):1116–1137

Gardecki R, Neumark D (1998) Order from chaos? The effects of early labor market experiences on adult labor market outcomes. Ind Labor Relat Rev 51(2):299–322

Gathmann C, Schönberg U (2010) How general is human capital? A task-based approach. J Labor Econ 28(1):1–49

Genda Y, Kondo A, Ohta S (2010) Long-term effects of a recession at labor market entry in Japan and the United States. J Hum Resour 45(1):157–196

Gibbons R, Waldman M (2006) Enriching a theory of wage and promotion dynamics inside firms. J Labor Econ 24(1):59–107

Giuliano P, Spilimbergo A (2009) Growing up in a recession. NBER working paper no. 15321. NBER, Cambridge

Kahn LB (2010) The long-term labor market consequences of graduating from college in a bad economy. Labour Econ 17(2):303–316

Kambourov G, Manovskii I (2009) Occupational specificity of human capital. Int Econ Rev 50(1):63–115

Kondo A (2008) Differential effects of graduating during a recession across race and gender. Columbia University, New York. Mimeo

Kondo A (2012) Gender-specific labor market conditions and family formation. J Popul Econ 25(1):151–174

Kwon I, Milgrom Meyersson EM, Hwang S (2010) Cohort effects in promotions and wages. Evidence from Sweden and the United States. J Hum Resour 45(3):772–808

Liu K, Salvanes KG, Sørensen EØ (2012) Good skills in bad times: cyclical skill mismatch and the long-term effects of graduating in a recession. IZA discussion paper 6820. IZA, Bonn

Mansour H (2009) The career effects of graduating from college in a bad economy: the role of workers’ ability. University of Colorado Denver, Denver. Mimeo

Moulton BR (1986) Random group effects and the precision of regression estimates. J Econometrics 32(3):385–397

Muehlemann S, Wolter SC, Wuest A (2009) Apprenticeship training and the business cycle. Empirical Res Vocat Educ Train 1(2):173–186

Murphy KM, Welch F (1990) Empirical age-earnings profiles. J Labor Econ 8(2):202–229

Neal D (1995) Industry-specific human capital: evidence from displaced workers. J Labor Econ 13(4):653–677

Neumark D (2002) Youth labor markets in the United States: shopping around vs staying put. Rev Econ Stat 84(3):462–482

Nijkamp P, Poot J (2005) The last word on the wage curve? J Econ Surv 19(3):421–450

Oreopoulos P, von Wachter T, Heisz A (2012) The short- and long-term career effects of graduating in a recession. Am Econ J Appl Econ 4(1):1–29

Oyer P (2006) Initial labor market conditions and long-term outcomes for economists. J Econ Perspect 20(3):143–160

Oyer P (2008) The making of an investment banker: stock market shocks, career choice, and lifetime income. J Financ 63(6):2601–2628

Parent D (2000) Industry-specific capital and the wage profile: evidence from the national longitudinal survey of youth and the panel study of income dynamics. J Labor Econ 18(2):306–323

Raaum O, Røed K (2006) Do business cycle conditions at the time of labor market entry affect future employment prospects? Rev Econ Stat 88(2):193–210

Schwerdt G, Ichino A, Ruf O, Winter-Ebmer R, Zweimüller J (2010) Does the color of the collar matter? Employment and earnings after plant closure. Econ Lett 108(2):137–140

Solon G, Barsky R, Parker JA (1994) Measuring the cyclicality of real wages: how important is composition bias? Q J Econ 109(1):1–25

Stevens K (2007) Adverse economic conditions at labour market entry: permanent scars or rapid catch-up? University College London, London. Mimeo

Sullivan P (2010) Empirical evidence on occupation and industry specific human capital. Labour Econ 17(3):567–580

Topel RH, Ward MP (1992) Job mobility and the careers of young men. Q J Econ 107(2):439–479

von Wachter T, Bender S (2008) Do initial conditions persist between firms? An analysis of firm-entry cohort effects and job losers using matched employer-employee data. In: Bender S, Lane J, Shaw KL, Andersson F, von Wachter T (eds) The analysis of firms and employees. Quantitative and qualitative approaches. National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, pp 135–162

von Wachter T, Bender S (2006) In the right place at the wrong time: the role of firms and luck in young workers’ careers. Am Econ Rev 96(5):1679–1705

Wozniak A (2010) Are college graduates more responsive to distant labor market opportunities? J Hum Resour 45(4):944–970

Zweimüller J, Winter-Ebmer R, Lalive R, Kuhn A, Ruf O, Wuellrich JP, Büchi S (2009) The Austrian social security database (ASSD). NRN: the Austrian center for labor economics and the analysis of the welfare state. Working paper 0903. NRN, Linz

Acknowledgments

We thank two anonymous referees, Joshua Angrist, Johann Brunner, Pierre Cahuc, Christian Dustmann, Marcus Hagedorn, Martin Halla, Christian Hepenstrick, Helmut Hofer, Steinar Holden, Bo Honoré, Rafael Lalive, Michael Lechner, Andrew Oswald, Tamas Papp, Michael Reiter, Steven Stillman, Petra Todd, Till von Wachter, Rudolf Winter-Ebmer, Andrea Weber, Tobias Würgler, Josef Zweimüller, seminar participants in Engelberg, Linz, Vienna, Weggis, and Zurich, as well as participants at the 2009 Spring Meeting of Young Economists in Istanbul, the 15th International Conference on Panel Data in Bonn, and the 13th IZA European Summer School in Labor Economics in Buch/Ammersee for helpful comments and suggestions at various stages of this project. Financial support by the Austrian Science Fund is gratefully acknowledged (“The Austrian Center for Labor Economics and the Analysis of the Welfare State”).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Junsen Zhang

Appendix

Sample construction

We first determine the start of the first regular employment spell for each male individual born between 1958 and 1985.Footnote

Obviously, an individual must be covered by the ASSD in order to be included in the sample. An individual is covered by the ASSD if he or she is entitled to future social security benefits (typically old-age benefits) or has already claimed social security benefits before first entering the labor force. Typically, individuals “enter” the ASSD once they start working.

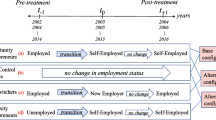

The restriction with respect to year of birth, in combination with the restriction on age at beginning of one’s first regular job that we apply below, ensures that the potential range of age at first entry into the labor force is the same for each entry cohort considered in the analysis (1978–2000). Additionally, we drop all individuals who were self-employed and/or worked as a farmer or civil servant at least once, because the data do not consistently cover these employment spells over the whole period of analysis and/or because earnings are not recorded (in the case of self-employment). We thus cannot fully observe the employment and/or earnings histories of such individuals.Obviously, an individual must be covered by the ASSD in order to be included in the sample. An individual is covered by the ASSD if he or she is entitled to future social security benefits (typically old-age benefits) or has already claimed social security benefits before first entering the labor force. Typically, individuals “enter” the ASSD once they start working.

We then determine each individual’s age at the start of his first regular employment spell starting between 1978 and 2000. We define regular employment as an employment spell which lasts for at least 180 days.Footnote

Importantly, vocational training such as apprenticeship training is not considered as regular employment (but as formal training).

We also focus on individuals aged between 16 and 21 years at the start of their first regular employment spell. This leaves us with 797,846 unique individuals (see Table 10), from which we take a simple 30 % random sample. This finally yields a total of 217,587 unique individuals and 3,349,075 observations (= individuals × years) when following these individuals over time.Table 10 shows descriptive statistics for some key variables, by individuals’ age at the time of first entry into the labor force. We consistently exclude individuals who start their first regular employment after they attain age 30 because they presumably never enter the labor force at all.FootnoteThe group of individuals who enter at a later age probably consists of two very different groups, who are indistinguishable from each other in the data. On the one hand, there are truly high-skilled workers who enter the labor market at a later stage because they continued their education until that time. On the other hand, however, there are also low-skilled workers who were never employed or only sporadically employed before starting their first regular employment. Because schooling is not directly observed, we would mix these two groups of workers together if we were to include them.

The first column of Table 10 shows descriptives for all individuals, and the second (third) column shows descriptives for individuals aged 16 to 21 (aged 22 to 30) when starting their first employment. A comparison of the second to the third columns shows that our sample restriction with respect to age at the start of first regular employment works as expected. The sample of lower-skilled workers, compared to the group of higher-skilled workers, contains a higher fraction of blue-collar workers and has considerably lower wages on average and shorter duration of the first regular employment spell.Importantly, vocational training such as apprenticeship training is not considered as regular employment (but as formal training).

The group of individuals who enter at a later age probably consists of two very different groups, who are indistinguishable from each other in the data. On the one hand, there are truly high-skilled workers who enter the labor market at a later stage because they continued their education until that time. On the other hand, however, there are also low-skilled workers who were never employed or only sporadically employed before starting their first regular employment. Because schooling is not directly observed, we would mix these two groups of workers together if we were to include them.

Also note that, for the group of individuals aged between 22 and 30 when first entering the labor force, highly skilled workers potentially are mixed up with lowly skilled workers: individuals in this group of workers either spent much time in education, were previously unemployed, or had short employment spells not counting as regular employment. This is apparent from the proportion of workers below the lower censoring point or above the higher censoring point. The probability of crossing any of the two points is higher for the sample of older workers. Consequently, the variation in the real daily wage (and thus productivity) is considerably smaller in the sample of younger workers than in the group of older workers.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brunner, B., Kuhn, A. The impact of labor market entry conditions on initial job assignment and wages. J Popul Econ 27, 705–738 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-013-0494-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-013-0494-4